A Case of Atrial Flutter Masking Acute Pericarditis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial

European Heart Journal (2004) Ã, 1–28 ESC Guidelines Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases Full Text The Task Force on the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology Task Force members, Bernhard Maisch, Chairperson* (Germany), Petar M. Seferovic (Serbia and Montenegro), Arsen D. Ristic (Serbia and Montenegro), Raimund Erbel (Germany), Reiner Rienmuller€ (Austria), Yehuda Adler (Israel), Witold Z. Tomkowski (Poland), Gaetano Thiene (Italy), Magdi H. Yacoub (UK) ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG), Silvia G. Priori (Chairperson) (Italy), Maria Angeles Alonso Garcia (Spain), Jean-Jacques Blanc (France), Andrzej Budaj (Poland), Martin Cowie (UK), Veronica Dean (France), Jaap Deckers (The Netherlands), Enrique Fernandez Burgos (Spain), John Lekakis (Greece), Bertil Lindahl (Sweden), Gianfranco Mazzotta (Italy), Joa~o Morais (Portugal), Ali Oto (Turkey), Otto A. Smiseth (Norway) Document Reviewers, Gianfranco Mazzotta, CPG Review Coordinator (Italy), Jean Acar (France), Eloisa Arbustini (Italy), Anton E. Becker (The Netherlands), Giacomo Chiaranda (Italy), Yonathan Hasin (Israel), Rolf Jenni (Switzerland), Werner Klein (Austria), Irene Lang (Austria), Thomas F. Luscher€ (Switzerland), Fausto J. Pinto (Portugal), Ralph Shabetai (USA), Maarten L. Simoons (The Netherlands), Jordi Soler Soler (Spain), David H. Spodick (USA) Table of contents Constrictive pericarditis . 9 Pericardial cysts . 13 Preamble . 2 Specific forms of pericarditis . 13 Introduction. 2 Viral pericarditis . 13 Aetiology and classification of pericardial disease. 2 Bacterial pericarditis . 14 Pericardial syndromes . ..................... 2 Tuberculous pericarditis . 14 Congenital defects of the pericardium . 2 Pericarditis in renal failure . 16 Acute pericarditis . 2 Autoreactive pericarditis and pericardial Chronic pericarditis . 6 involvement in systemic autoimmune Recurrent pericarditis . 6 diseases . 16 Pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade . -

Myocarditis, Pericarditis and Other Pericardial Diseases

Heart 2000;84:449–454 Diagnosis is easiest during epidemics of cox- GENERAL CARDIOLOGY sackie infections but diYcult in isolated cases. Heart: first published as 10.1136/heart.84.4.449 on 1 October 2000. Downloaded from These are not seen by cardiologists unless they develop arrhythmia, collapse or suVer chest Myocarditis, pericarditis and other pain, the majority being dealt with in the primary care system. pericardial diseases Acute onset of chest pain is usual and may mimic myocardial infarction or be associated 449 Celia M Oakley with pericarditis. Arrhythmias or conduction Imperial College School of Medicine, Hammersmith Hospital, disturbances may be life threatening despite London, UK only mild focal injury, whereas more wide- spread inflammation is necessary before car- diac dysfunction is suYcient to cause symp- his article discusses the diagnosis and toms. management of myocarditis and peri- Tcarditis (both acute and recurrent), as Investigations well as other pericardial diseases. The ECG may show sinus tachycardia, focal or generalised abnormality, ST segment eleva- tion, fascicular blocks or atrioventricular con- Myocarditis duction disturbances. Although the ECG abnormalities are non-specific, the ECG has Myocarditis is the term used to indicate acute the virtue of drawing attention to the heart and infective, toxic or autoimmune inflammation of leading to echocardiographic and other investi- the heart. Reversible toxic myocarditis occurs gations. Echocardiography may reveal segmen- in diphtheria and sometimes in infective endo- -

Atrial Flutter Patient Information

AF A Atrial flutter patient information Providing information, support and access to established, new or innovative treatments for atrial fibrillation www.afa-international.org Registered Charity No. 1122442 Glossary Antiarrhythmic drugs Drugs used to restore the Contents normal heart rhythm Introduction Anticoagulant A group of drugs which help to thin the blood and prevent AF-related stroke What is atrial flutter? Arrhythmia A heart rhythm disorder What causes atrial flutter? Atrial flutter A rhythm disorder characterised by a rapid but regular atrial rate although not as high as What are the atrial fibrillation symptoms of atrial flutter? A therapy to treat arrhythmias Cardioversion How do I get to which uses a transthoracic electrical shock to revert see the right doctor the heart back into a normal rhythm to treat my atrial flutter? Catheter ablation A treatment by which the small area inside the heart which has been causing atrial What are the risks flutter is destroyed of atrial flutter? Echocardiogram An image of the heart using Diagnosis and echocardiography or soundwave-based technology. treatment An echocardiogram (nicknamed ‘echo’) shows a three-dimensional shot of the heart Treatment of atrial flutter Electrocardiogram (ECG) A representation of the heart’s electrical activity in the form of wavy lines. Drug treatments An ECG is taken from electrodes on the skin surface Stroke prevention The inability (failure) of the heart to Heart failure Non-drug treatments pump sufficient oxygenated blood around the body to meet physiological requirements 2 Introduction Atrial flutter is a relatively common heart rhythm The heart disturbance encountered by doctors, although not and normal as common as atrial fibrillation (AF). -

Basic Rhythm Recognition

Electrocardiographic Interpretation Basic Rhythm Recognition William Brady, MD Department of Emergency Medicine Cardiac Rhythms Anatomy of a Rhythm Strip A Review of the Electrical System Intrinsic Pacemakers Cells These cells have property known as “Automaticity”— means they can spontaneously depolarize. Sinus Node Primary pacemaker Fires at a rate of 60-100 bpm AV Junction Fires at a rate of 40-60 bpm Ventricular (Purkinje Fibers) Less than 40 bpm What’s Normal P Wave Atrial Depolarization PR Interval (Normal 0.12-0.20) Beginning of the P to onset of QRS QRS Ventricular Depolarization QRS Interval (Normal <0.10) Period (or length of time) it takes for the ventricles to depolarize The Key to Success… …A systematic approach! Rate Rhythm P Waves PR Interval P and QRS Correlation QRS Rate Pacemaker A rather ill patient……… Very apparent inferolateral STEMI……with less apparent complete heart block RATE . Fast vs Slow . QRS Width Narrow QRS Wide QRS Narrow QRS Wide QRS Tachycardia Tachycardia Bradycardia Bradycardia Regular Irregular Regular Irregular Sinus Brady Idioventricular A-Fib / Flutter Bradycardia w/ BBB Sinus Tach A-Fib VT PVT Junctional 2 AVB / II PSVT A-Flutter SVT aberrant A-Fib 1 AVB 3 AVB A-Flutter MAT 2 AVB / I or II PAT PAT 3 AVB ST PAC / PVC Stability Hypotension / hypoperfusion Altered mental status Chest pain – Coronary ischemic Dyspnea – Pulmonary edema Sinus Rhythm Sinus Rhythm P Wave PR Interval QRS Rate Rhythm Pacemaker Comment . Before . Constant, . Rate 60-100 . Regular . SA Node Upright in each QRS regular . Interval =/< leads I, II, . Look . Interval .12- .10 & III alike .20 Conduction Image reference: Cardionetics/ http://www.cardionetics.com/docs/healthcr/ecg/arrhy/0100_bd.htm Sinus Pause A delay of activation within the atria for a period between 1.7 and 3 seconds A palpitation is likely to be felt by the patient as the sinus beat following the pause may be a heavy beat. -

Pericardial Disease and Other Acquired Heart Diseases

Royal Brompton & Harefield NHS Foundation Trust Pericardial disease and other acquired heart diseases Sylvia Krupickova Exam oriented Echocardiography course, 4th November 2016 Normal Pericardium: 2 layers – fibrous - serous – visceral and parietal layer 2 pericardial sinuses – (not continuous with one another): • Transverse sinus – between in front aorta and pulmonary artery and posterior vena cava superior • Oblique sinus - posterior to the heart, with the vena cava inferior on the right side and left pulmonary veins on the left side Normal pericardium is not seen usually on normal echocardiogram, neither the pericardial fluid Acute Pericarditis: • How big is the effusion? (always measure in diastole) • Where is it? (appears first behind the LV) • Is it causing haemodynamic compromise? Small effusion – <10mm, black space posterior to the heart in parasternal short and long axis views, seen only in systole Moderate – 10-20 mm, more than 25 ml in adult, echo free space is all around the heart throughout the cardiac cycle Large – >20 mm, swinging motion of the heart in the pericardial cavity Pericardiocentesis Constrictive pericarditis Constriction of LV filling by pericardium Restriction versus Constriction: Restrictive cardiomyopathy Impaired relaxation of LV Constriction versus Restriction Both have affected left ventricular filling Constriction E´ velocity is normal as there is no impediment to relaxation of the left ventricle. Restriction E´ velocity is low (less than 5 cm/s) due to impaired filling of the ventricle (impaired relaxation) -

Case Report: Cytarabine-Induced Pericarditis and Pericardial Effusion Rino Sato, MD and Robert Park, MD

HEMATOLOGY & ONCOLOGY Case Report: Cytarabine-Induced Pericarditis and Pericardial Effusion Rino Sato, MD and Robert Park, MD INTRODUCTION for inpatient chemotherapy, and demonstrated mild global left ventricular dysfunction with ejection fraction Cytarabine (cytosine arabinoside, Ara-C) is an antime- of 40%. The cardiomyopathy was attributed to his tabolite analogue of cytidine that is used as a chemo- underlying hypertension or sleep apnea, and not therapeutic agent for the treatment of acute myelogenous coronary artery disease based on a normal coronary leukemia and lymphocytic leukemias1 . The most computed tomography (CT) angiogram. The patient common side effects of this therapy include myelosup- was started on induction therapy with high-dose pression, pancytopenia, hepatotoxicity, gastrointestinal cytarabine therapy at 3g/m2 every twelve hours without ulceration with bleeding, and pulmonary infiltrates2. an anthracycline agent such as doxorubicin. Cardio-pulmonary complications of cytarabine therapy are uncommon, but include supraventricular and On day 5 of cytarabine therapy, the patient developed ventricular arrhythmias, sinus bradycardia, and recurrent non-radiating sharp chest pain that worsened with heart failure2, 3. Occasionally, patients may develop inspiration and palpation. He had no cough or sputum pericarditis leading to pericardial tamponade, which can production. His cardiac exam revealed a tri-phasic, be fatal. We report a case of cytarabine-induced high-pitched friction rub best heard over the left lower pericarditis and pericardial effusion to increase awareness sternal border. He was normotensive, did not have pulsus about this serious side effect of cytarabine and review paradoxus, and had minimally distended jugular veins. the current literature. An electrocardiogram revealed widespread concave ST-elevation and PR-depression in the limb leads (I, II, III, CASE PRESENTATION avF) and precordial leads (V5-V6) concerning for acute pericarditis (Figure 1). -

Acute Non-Specific Pericarditis R

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.43.502.534 on 1 August 1967. Downloaded from Postgrad. med. J. (August 1967) 43, 534-538. CURRENT SURVEY Acute non-specific pericarditis R. G. GOLD * M.B., B.S., M.RA.C.P., M.R.C.P. Senior Registrar, Cardiac Department, Brompton Hospital, London, S.W.3 Incidence neck, to either flank and frequently through to the Acute non-specific pericarditis (acute benign back. Occasionally pain is experienced on swallow- pericarditis; acute idiopathic pericarditis) has been ing (McGuire et al., 1954) and this was the pre- recognized for over 100 years (Christian, 1951). In senting symptom in one of our own patients. Mild 1942 Barnes & Burchell described fourteen cases attacks of premonitory chest pain may occur up to of the condition and since then several series of 4 weeks before the main onset of symptoms cases have been published (Krook, 1954; Scherl, (Martin, 1966). Malaise is very common, and is 1956; Swan, 1960; Martin, 1966; Logue & often severe and accompanied by listlessness and Wendkos, 1948). depression. The latter symptom is especially com- Until recently Swan's (1960) series of fourteen mon in patients suffering multiple relapses or patients was the largest collection of cases in this prolonged attacks, but is only partly related to the country. In 1966 Martin was able to collect most length of the illness and fluctuates markedly from of his nineteen cases within 1 year in a 550-bed day to day with the patient's general condition. hospital. The disease is thus by no means rare and Tachycardia occurs in almost every patient at warrants greater attention than has previously some stage of the illness. -

SIGN 152 • Cardiac Arrhythmias in Coronary Heart Disease

www.healthcareimprovementscotland.org Edinburgh Office | Gyle Square |1 South Gyle Crescent | Edinburgh | EH12 9EB Telephone 0131 623 4300 Fax 0131 623 4299 Glasgow Office | Delta House | 50 West Nile Street | Glasgow | G1 2NP Telephone 0141 225 6999 Fax 0141 248 3776 The Healthcare Environment Inspectorate, the Scottish Health Council, the Scottish Health Technologies Group, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) and the Scottish Medicines Consortium are key components of our organisation. SIGN 152 • Cardiac arrhythmias in coronary heart disease A national clinical guideline September 2018 Evidence KEY TO EVIDENCE STATEMENTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS LEVELS OF EVIDENCE 1++ High-quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a very low risk of bias 1+ Well-conducted meta-analyses, systematic reviews, or RCTs with a low risk of bias 1 - Meta-analyses, systematic reviews, or RCTs with a high risk of bias High-quality systematic reviews of case-control or cohort studies ++ 2 High-quality case-control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding or bias and a high probability that the relationship is causal Well-conducted case-control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding or bias and a moderate probability that the 2+ relationship is causal 2 - Case-control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding or bias and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal 3 Non-analytic studies, eg case reports, case series 4 Expert opinion RECOMMENDATIONS Some recommendations can be made with more certainty than others. The wording used in the recommendations in this guideline denotes the certainty with which the recommendation is made (the ‘strength’ of the recommendation). -

Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function

ASE/EACVI GUIDELINES AND STANDARDS Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging Sherif F. Nagueh, Chair, MD, FASE,1 Otto A. Smiseth, Co-Chair, MD, PhD,2 Christopher P. Appleton, MD,1 Benjamin F. Byrd, III, MD, FASE,1 Hisham Dokainish, MD, FASE,1 Thor Edvardsen, MD, PhD,2 Frank A. Flachskampf, MD, PhD, FESC,2 Thierry C. Gillebert, MD, PhD, FESC,2 Allan L. Klein, MD, FASE,1 Patrizio Lancellotti, MD, PhD, FESC,2 Paolo Marino, MD, FESC,2 Jae K. Oh, MD,1 Bogdan Alexandru Popescu, MD, PhD, FESC, FASE,2 and Alan D. Waggoner, MHS, RDCS1, Houston, Texas; Oslo, Norway; Phoenix, Arizona; Nashville, Tennessee; Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; Uppsala, Sweden; Ghent and Liege, Belgium; Cleveland, Ohio; Novara, Italy; Rochester, Minnesota; Bucharest, Romania; and St. Louis, Missouri (J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2016;29:277-314.) Keywords: Diastole, Echocardiography, Doppler, Heart failure TABLE OF CONTENTS I. General Principles for Echocardiographic Assessment of LV Diastolic F. Atrioventricular Block and Pacing 296 Function 278 VI. Diastolic Stress Test 298 II. Diagnosis of Diastolic Dysfunction in the Presence of Normal A. Indications 299 LVEF 279 B. Performance 299 III. Echocardiographic Assessment of LV Filling Pressures and Diastolic C. Interpretation 301 Dysfunction Grade 281 D. Detection of Early Myocardial Disease and Prognosis 301 IV. Conclusions on Diastolic Function in the Clinical Report 288 VII. Novel Indices of LV Diastolic Function 301 V. Estimation of LV Filling Pressures in Specific Cardiovascular VIII. Diastolic Doppler and 2D Imaging Variables for Prognosis in Patients Diseases 288 with HFrEF 303 A. -

Quick Quiz What Is the Diagnosis? Background

QUICK QUIZ WHAT IS THE DIAGNOSIS? BACKGROUND An 82-year-old man is brought in to the emergency department by ambulance because of a sudden loss of consciousness, which occurred at home while he was walking to the bathroom. The patient's wife heard a thump from the other room and came to find her husband lying on the floor. She reported that his upper extremities twitched a couple of times, and his eyes rolled back, but within a minute he was awake and alert and asking what had happened. He remained stable during transport and the main finding that the paramedics mentioned was that his pulse seemed irregular and sometimes slow. On arrival the patient was alert and awake with his baseline normal mental status; he was not groggy or confused. Given the lack of premonitory symptoms and the abnormal pulse rhythm, you are concerned that the patient has had cardiac syncope. The monitor shows an irregularly irregular rhythm and a heart rate of 62 bpm. The patient's blood pressure is 150/82 mm Hg, and his oxygen saturation is 99% on room air. You ask for a 12-lead ECG. QUESTIONS 1. What is the diagnosis? 2. What else should you consider? 3. What is the treatment? CAP 5, CAP 25, HAP 5, HAP 23 Scott Taylor 2016 ANSWERS & DISCUSSION 1. Diagnosis Atrial flutter with variable block Note the sawtooth f waves in the inferior leads (II, III, aVF) and in V1. These leads are usually where flutter waves are most easily recognized. Also note the variability in the timing of the QRS complexes that follow. -

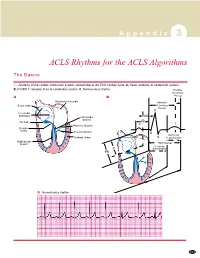

ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms

A p p e n d i x 3 ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms The Basics 1. Anatomy of the cardiac conduction system: relationship to the ECG cardiac cycle. A, Heart: anatomy of conduction system. B, P-QRS-T complex: lines to conduction system. C, Normal sinus rhythm. Relative Refractory A B Period Bachmann’s bundle Absolute Sinus node Refractory Period R Internodal pathways Left bundle AVN branch AV node PR T Posterior division P Bundle of His Anterior division Q Ventricular Purkinje fibers S Repolarization Right bundle branch QT Interval Ventricular P Depolarization PR C Normal sinus rhythm 253 A p p e n d i x 3 The Cardiac Arrest Rhythms 2. Ventricular Fibrillation/Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia Pathophysiology ■ Ventricles consist of areas of normal myocardium alternating with areas of ischemic, injured, or infarcted myocardium, leading to chaotic pattern of ventricular depolarization Defining Criteria per ECG ■ Rate/QRS complex: unable to determine; no recognizable P, QRS, or T waves ■ Rhythm: indeterminate; pattern of sharp up (peak) and down (trough) deflections ■ Amplitude: measured from peak-to-trough; often used subjectively to describe VF as fine (peak-to- trough 2 to <5 mm), medium-moderate (5 to <10 mm), coarse (10 to <15 mm), very coarse (>15 mm) Clinical Manifestations ■ Pulse disappears with onset of VF ■ Collapse, unconsciousness ■ Agonal breaths ➔ apnea in <5 min ■ Onset of reversible death Common Etiologies ■ Acute coronary syndromes leading to ischemic areas of myocardium ■ Stable-to-unstable VT, untreated ■ PVCs with -

ECG in Pericarditis Pericardial Effusion Pericardium the Pericardium Is a Double Sheet Made up by Two Layers of Not So Distensible Fibrous Tissue That Wraps the Heart

Pericardial effusion with emphasis on the electrocardiographic aspects By Andrés Ricardo Pérez-Riera MDPhD ECG In pericarditis Pericardial effusion Pericardium The pericardium is a double sheet made up by two layers of not so distensible fibrous tissue that wraps the heart. The internal or visceral layer is adhered to the heart. The external or parietal layer is wrapped by the visceral one. Between both there is a space with a small amount of serofibrinous liquid (ö20 to 50 ml). The parietal layer fixes the heart in its place within the chest and prevents direct contact between the organ and neighboring structures. Functions of the pericardium The pericardium has three main functions: mechanical, membranous and ligamentous. Mechanical function: it restricts cardiac dilatation increasing the efficiency of the heart, maintaining ventricular compliance and distributing hydrostatic forces. Additionally, it creates a closed chamber with subatmospheric pressure, aiding atrial filling and reducing parietal transmural pressures. Membranous function: it protects the heart, reducing its external friction and acting as a barrier against propagation of infections and neoplasia’s. Ligamentous function: it anatomically fixes the heart, preventing the latter from balancing. Other functions: Barrier against infections; barrier against dissemination of neoplasias; preventing excessive movements of the organ; preventing direct contact of the heart with neighboring structures; conditioning less friction between the heart and other organs; allowing diastolic distention of the chambers due to negative atmospheric pressure. Pericarditis Concept of pericarditis: syndrome caused by inflammation of the pericardium, a sack made up by two sheets (parietal and visceral) that wrap the heart and the great vessels. Etiological classification of pericarditis • Idiopathic (unknown): 26-86% of cases.