Atrial Flutter: a Review of Its History, Mechanisms, Clinical Features, and Current Therapy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atrial Flutter Patient Information

AF A Atrial flutter patient information Providing information, support and access to established, new or innovative treatments for atrial fibrillation www.afa-international.org Registered Charity No. 1122442 Glossary Antiarrhythmic drugs Drugs used to restore the Contents normal heart rhythm Introduction Anticoagulant A group of drugs which help to thin the blood and prevent AF-related stroke What is atrial flutter? Arrhythmia A heart rhythm disorder What causes atrial flutter? Atrial flutter A rhythm disorder characterised by a rapid but regular atrial rate although not as high as What are the atrial fibrillation symptoms of atrial flutter? A therapy to treat arrhythmias Cardioversion How do I get to which uses a transthoracic electrical shock to revert see the right doctor the heart back into a normal rhythm to treat my atrial flutter? Catheter ablation A treatment by which the small area inside the heart which has been causing atrial What are the risks flutter is destroyed of atrial flutter? Echocardiogram An image of the heart using Diagnosis and echocardiography or soundwave-based technology. treatment An echocardiogram (nicknamed ‘echo’) shows a three-dimensional shot of the heart Treatment of atrial flutter Electrocardiogram (ECG) A representation of the heart’s electrical activity in the form of wavy lines. Drug treatments An ECG is taken from electrodes on the skin surface Stroke prevention The inability (failure) of the heart to Heart failure Non-drug treatments pump sufficient oxygenated blood around the body to meet physiological requirements 2 Introduction Atrial flutter is a relatively common heart rhythm The heart disturbance encountered by doctors, although not and normal as common as atrial fibrillation (AF). -

Basic Rhythm Recognition

Electrocardiographic Interpretation Basic Rhythm Recognition William Brady, MD Department of Emergency Medicine Cardiac Rhythms Anatomy of a Rhythm Strip A Review of the Electrical System Intrinsic Pacemakers Cells These cells have property known as “Automaticity”— means they can spontaneously depolarize. Sinus Node Primary pacemaker Fires at a rate of 60-100 bpm AV Junction Fires at a rate of 40-60 bpm Ventricular (Purkinje Fibers) Less than 40 bpm What’s Normal P Wave Atrial Depolarization PR Interval (Normal 0.12-0.20) Beginning of the P to onset of QRS QRS Ventricular Depolarization QRS Interval (Normal <0.10) Period (or length of time) it takes for the ventricles to depolarize The Key to Success… …A systematic approach! Rate Rhythm P Waves PR Interval P and QRS Correlation QRS Rate Pacemaker A rather ill patient……… Very apparent inferolateral STEMI……with less apparent complete heart block RATE . Fast vs Slow . QRS Width Narrow QRS Wide QRS Narrow QRS Wide QRS Tachycardia Tachycardia Bradycardia Bradycardia Regular Irregular Regular Irregular Sinus Brady Idioventricular A-Fib / Flutter Bradycardia w/ BBB Sinus Tach A-Fib VT PVT Junctional 2 AVB / II PSVT A-Flutter SVT aberrant A-Fib 1 AVB 3 AVB A-Flutter MAT 2 AVB / I or II PAT PAT 3 AVB ST PAC / PVC Stability Hypotension / hypoperfusion Altered mental status Chest pain – Coronary ischemic Dyspnea – Pulmonary edema Sinus Rhythm Sinus Rhythm P Wave PR Interval QRS Rate Rhythm Pacemaker Comment . Before . Constant, . Rate 60-100 . Regular . SA Node Upright in each QRS regular . Interval =/< leads I, II, . Look . Interval .12- .10 & III alike .20 Conduction Image reference: Cardionetics/ http://www.cardionetics.com/docs/healthcr/ecg/arrhy/0100_bd.htm Sinus Pause A delay of activation within the atria for a period between 1.7 and 3 seconds A palpitation is likely to be felt by the patient as the sinus beat following the pause may be a heavy beat. -

SIGN 152 • Cardiac Arrhythmias in Coronary Heart Disease

www.healthcareimprovementscotland.org Edinburgh Office | Gyle Square |1 South Gyle Crescent | Edinburgh | EH12 9EB Telephone 0131 623 4300 Fax 0131 623 4299 Glasgow Office | Delta House | 50 West Nile Street | Glasgow | G1 2NP Telephone 0141 225 6999 Fax 0141 248 3776 The Healthcare Environment Inspectorate, the Scottish Health Council, the Scottish Health Technologies Group, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) and the Scottish Medicines Consortium are key components of our organisation. SIGN 152 • Cardiac arrhythmias in coronary heart disease A national clinical guideline September 2018 Evidence KEY TO EVIDENCE STATEMENTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS LEVELS OF EVIDENCE 1++ High-quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a very low risk of bias 1+ Well-conducted meta-analyses, systematic reviews, or RCTs with a low risk of bias 1 - Meta-analyses, systematic reviews, or RCTs with a high risk of bias High-quality systematic reviews of case-control or cohort studies ++ 2 High-quality case-control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding or bias and a high probability that the relationship is causal Well-conducted case-control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding or bias and a moderate probability that the 2+ relationship is causal 2 - Case-control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding or bias and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal 3 Non-analytic studies, eg case reports, case series 4 Expert opinion RECOMMENDATIONS Some recommendations can be made with more certainty than others. The wording used in the recommendations in this guideline denotes the certainty with which the recommendation is made (the ‘strength’ of the recommendation). -

Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function

ASE/EACVI GUIDELINES AND STANDARDS Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging Sherif F. Nagueh, Chair, MD, FASE,1 Otto A. Smiseth, Co-Chair, MD, PhD,2 Christopher P. Appleton, MD,1 Benjamin F. Byrd, III, MD, FASE,1 Hisham Dokainish, MD, FASE,1 Thor Edvardsen, MD, PhD,2 Frank A. Flachskampf, MD, PhD, FESC,2 Thierry C. Gillebert, MD, PhD, FESC,2 Allan L. Klein, MD, FASE,1 Patrizio Lancellotti, MD, PhD, FESC,2 Paolo Marino, MD, FESC,2 Jae K. Oh, MD,1 Bogdan Alexandru Popescu, MD, PhD, FESC, FASE,2 and Alan D. Waggoner, MHS, RDCS1, Houston, Texas; Oslo, Norway; Phoenix, Arizona; Nashville, Tennessee; Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; Uppsala, Sweden; Ghent and Liege, Belgium; Cleveland, Ohio; Novara, Italy; Rochester, Minnesota; Bucharest, Romania; and St. Louis, Missouri (J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2016;29:277-314.) Keywords: Diastole, Echocardiography, Doppler, Heart failure TABLE OF CONTENTS I. General Principles for Echocardiographic Assessment of LV Diastolic F. Atrioventricular Block and Pacing 296 Function 278 VI. Diastolic Stress Test 298 II. Diagnosis of Diastolic Dysfunction in the Presence of Normal A. Indications 299 LVEF 279 B. Performance 299 III. Echocardiographic Assessment of LV Filling Pressures and Diastolic C. Interpretation 301 Dysfunction Grade 281 D. Detection of Early Myocardial Disease and Prognosis 301 IV. Conclusions on Diastolic Function in the Clinical Report 288 VII. Novel Indices of LV Diastolic Function 301 V. Estimation of LV Filling Pressures in Specific Cardiovascular VIII. Diastolic Doppler and 2D Imaging Variables for Prognosis in Patients Diseases 288 with HFrEF 303 A. -

Quick Quiz What Is the Diagnosis? Background

QUICK QUIZ WHAT IS THE DIAGNOSIS? BACKGROUND An 82-year-old man is brought in to the emergency department by ambulance because of a sudden loss of consciousness, which occurred at home while he was walking to the bathroom. The patient's wife heard a thump from the other room and came to find her husband lying on the floor. She reported that his upper extremities twitched a couple of times, and his eyes rolled back, but within a minute he was awake and alert and asking what had happened. He remained stable during transport and the main finding that the paramedics mentioned was that his pulse seemed irregular and sometimes slow. On arrival the patient was alert and awake with his baseline normal mental status; he was not groggy or confused. Given the lack of premonitory symptoms and the abnormal pulse rhythm, you are concerned that the patient has had cardiac syncope. The monitor shows an irregularly irregular rhythm and a heart rate of 62 bpm. The patient's blood pressure is 150/82 mm Hg, and his oxygen saturation is 99% on room air. You ask for a 12-lead ECG. QUESTIONS 1. What is the diagnosis? 2. What else should you consider? 3. What is the treatment? CAP 5, CAP 25, HAP 5, HAP 23 Scott Taylor 2016 ANSWERS & DISCUSSION 1. Diagnosis Atrial flutter with variable block Note the sawtooth f waves in the inferior leads (II, III, aVF) and in V1. These leads are usually where flutter waves are most easily recognized. Also note the variability in the timing of the QRS complexes that follow. -

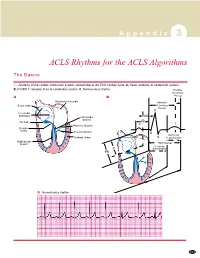

ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms

A p p e n d i x 3 ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms The Basics 1. Anatomy of the cardiac conduction system: relationship to the ECG cardiac cycle. A, Heart: anatomy of conduction system. B, P-QRS-T complex: lines to conduction system. C, Normal sinus rhythm. Relative Refractory A B Period Bachmann’s bundle Absolute Sinus node Refractory Period R Internodal pathways Left bundle AVN branch AV node PR T Posterior division P Bundle of His Anterior division Q Ventricular Purkinje fibers S Repolarization Right bundle branch QT Interval Ventricular P Depolarization PR C Normal sinus rhythm 253 A p p e n d i x 3 The Cardiac Arrest Rhythms 2. Ventricular Fibrillation/Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia Pathophysiology ■ Ventricles consist of areas of normal myocardium alternating with areas of ischemic, injured, or infarcted myocardium, leading to chaotic pattern of ventricular depolarization Defining Criteria per ECG ■ Rate/QRS complex: unable to determine; no recognizable P, QRS, or T waves ■ Rhythm: indeterminate; pattern of sharp up (peak) and down (trough) deflections ■ Amplitude: measured from peak-to-trough; often used subjectively to describe VF as fine (peak-to- trough 2 to <5 mm), medium-moderate (5 to <10 mm), coarse (10 to <15 mm), very coarse (>15 mm) Clinical Manifestations ■ Pulse disappears with onset of VF ■ Collapse, unconsciousness ■ Agonal breaths ➔ apnea in <5 min ■ Onset of reversible death Common Etiologies ■ Acute coronary syndromes leading to ischemic areas of myocardium ■ Stable-to-unstable VT, untreated ■ PVCs with -

Atrial Fibrillation with Flutter Episode in Patient with Mitral Stenosis Deri Arara1, Yerizal Karani2 1

Majalah Kedokteran Andalas http://jurnalmka.fk.unand.ac.id Vol. 41, No. 3, September 2018, Pages. 134-142 CASE REPORT Atrial fibrillation with flutter episode in patient with mitral stenosis Deri Arara1, Yerizal Karani2 1. Eka Hospital, Pekanbaru; 2. Cardiology and Vascular Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Andalas Correspondence: Deri Arara, email: [email protected] Abstract Mitral stenosis (MS) is a condition which happened because of congenital or acquired event. The most common etiology of MS in Indonesia is Rheumatic Heart Disease (RHD). Chronic inflammation on the mitral valve could lead to stenosis from mild to severe degree. Mitral stenosis could lead to many complications such as pulmonary hypertension and atrial fibrillation (AF). The prevalence of AF in patients with MS is related to the severity of valve obstruction and patient age. AF event in patient with MS could be happen because of Left Atrial (LA) dilatation of the patient. The mechanism that responsible for AF in patient with MS is a complex one. AF even with or without atrial flutter episode could lead a deterioration of patient hemodynamic. In the other way, the patient also predisposes to left atrial thrombus formation and systemic embolic events. Good awareness in diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation in patient with MS are mandatory to reduce the morbidity and mortality. Keywords: atrial fibrillation; atrial flutter; mitral stenosis; rheumatic heart disease Abstrak Mitral stenosis (MS) adalah suatu kondisi yang terjadi karena kejadian bawaan atau didapat. Etiologi MS yang paling umum di Indonesia adalah Penyakit Jantung Rematik (PJR). Peradangan kronis pada katup mitral dapat menyebabkan stenosis dari derajat ringan ke berat. -

Cardiac Arrhythmias in Acute Coronary Syndromes: Position Paper from the Joint EHRA, ACCA, and EAPCI Task Force

FOCUS ARTICLE Euro Intervention 2014;10-online publish-ahead-of-print August 2014 Cardiac arrhythmias in acute coronary syndromes: position paper from the joint EHRA, ACCA, and EAPCI task force Bulent Gorenek*† (Chairperson, Turkey), Carina Blomström Lundqvist† (Sweden), Josep Brugada Terradellas† (Spain), A. John Camm† (UK), Gerhard Hindricks† (Germany), Kurt Huber‡ (Austria), Paulus Kirchhof† (UK), Karl-Heinz Kuck† (Germany), Gulmira Kudaiberdieva† (Turkey), Tina Lin† (Germany), Antonio Raviele† (Italy), Massimo Santini† (Italy), Roland Richard Tilz† (Germany), Marco Valgimigli¶ (The Netherlands), Marc A. Vos† (The Netherlands), Christian Vrints‡ (Belgium), and Uwe Zeymer‡ (Germany) Document Reviewers: Gregory Y.H. Lip (Review Coordinator) (UK), Tatjania Potpara (Serbia), Laurent Fauchier (France), Christian Sticherling (Switzerland), Marco Roffi (Switzerland), Petr Widimsky (Czech Republic), Julinda Mehilli (Germany), Maddalena Lettino (Italy), Francois Schiele (France), Peter Sinnaeve (Belgium), Giueseppe Boriani (Italy), Deirdre Lane (UK), and Irene Savelieva (on behalf of EP-Europace, UK) Introduction treatment. Atrial fibrillation (AF) may also warrant urgent treat- It is known that myocardial ischaemia and infarction leads to severe ment when a fast ventricular rate is associated with hemodynamic metabolic and electrophysiological changes that induce silent or deterioration. The management of other arrhythmias is also based symptomatic life-threatening arrhythmias. Sudden cardiac death is largely on symptoms rather than to avert -

Unusual Presentation of Atrial Flutter with Slow Ventricular Response

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.15801 Unusual Presentation of Atrial Flutter With Slow Ventricular Response Varun Dobariya 1 , Ebubechukwu Ezeh 1 , Mohamed S. Suliman 1 , Davinder Singh 1 , Samson Teka 1 1. Internal Medicine, Marshall University, Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine, Huntington, USA Corresponding author: Varun Dobariya, [email protected] Abstract Atrial flutter is usually associated with tachycardia with a ventricular rate of 150 beats per minute. Less commonly, it may be associated with a slow ventricular response (SVR). This is typically seen in patients taking atrioventricular (AV) nodal blocking agents such as beta-blockers. In the absence of these drugs, atrial flutter with SVR may suggest intrinsic AV nodal disease, electrolyte disturbances, or atrial disease. We present a case of atrial flutter with SVR in a patient who was not receiving AV nodal blocking agents. Categories: Cardiology, Internal Medicine, Medical Education Keywords: bradycardia, atrial flutter, intrinsic av nodal disease, tachycardia, slow ventricular response Introduction Although less common, atrial flutter occurs in many of the same situations as atrial fibrillation. It may represent a stable rhythm or a bridge arrhythmia between sinus rhythm and atrial fibrillation [1]. It may be symptomatic or asymptomatic. When symptomatic, common presentations include palpitations, shortness of breath, fatigue, lightheadedness, as well as an increased risk of atrial thrombus formation that may cause cerebral and/or systemic embolization [1]. Electrocardiography (ECG) remains the mainstay of diagnosis. It shows the characteristic negative sawtooth flutter waves in the inferior leads. Atrial flutter typically causes tachycardia. Less commonly, it may also be associated with a normal heart rate (HR) or even bradycardia, as seen in our patient [2]. -

Management of Asymptomatic Arrhythmias

Europace (2019) 0, 1–32 EHRA POSITION PAPER doi:10.1093/europace/euz046 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/europace/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/europace/euz046/5382236 by PPD Development LP user on 25 April 2019 Management of asymptomatic arrhythmias: a European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) consensus document, endorsed by the Heart Failure Association (HFA), Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), Cardiac Arrhythmia Society of Southern Africa (CASSA), and Latin America Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS) David O. Arnar (Iceland, Chair)1*, Georges H. Mairesse (Belgium, Co-Chair)2, Giuseppe Boriani (Italy)3, Hugh Calkins (USA, HRS representative)4, Ashley Chin (South Africa, CASSA representative)5, Andrew Coats (United Kingdom, HFA representative)6, Jean-Claude Deharo (France)7, Jesper Hastrup Svendsen (Denmark)8,9, Hein Heidbu¨chel (Belgium)10, Rodrigo Isa (Chile, LAHRS representative)11, Jonathan M. Kalman (Australia, APHRS representative)12,13, Deirdre A. Lane (United Kingdom)14,15, Ruan Louw (South Africa, CASSA representative)16, Gregory Y. H. Lip (United Kingdom, Denmark)14,15, Philippe Maury (France)17, Tatjana Potpara (Serbia)18, Frederic Sacher (France)19, Prashanthan Sanders (Australia, APHRS representative)20, Niraj Varma (USA, HRS representative)21, and Laurent Fauchier (France)22 ESC Scientific Document Group: Kristina Haugaa23,24, Peter Schwartz25, Andrea Sarkozy26, Sanjay Sharma27, Erik Kongsga˚rd28, Anneli Svensson29, Radoslaw Lenarczyk30, Maurizio Volterrani31, Mintu Turakhia32, -

Atrial Fibrillation and Flutter in Primary Care

Atrial fibrillation and flutter in primary care Atrial fibrillation is under-diagnosed and under-treated Atrial fibrillation or flutter (AF)* occurs in approximately 1% of the general population. The prevalence doubles with each successive decade over the age of 50 years and it occurs in approximately 10% of people over the age of 80 years. An estimated 30 to 40 thousand people in New Zealand have AF and about one-third of these are unaware of it. Most GPs probably have some patients with undiagnosed AF. People with AF are at increased risk of stroke, heart failure and other cardiovascular events. AF is associated with doubling of mortality rates, mainly due to ischaemic stroke. Overall the risk of ischaemic stroke in people with AF is approximately 5% per year but this risk is not evenly distributed across people with this arrhythmia. For people at high risk, the benefits of warfarin to lower this risk, outweighs the risks of serious bleeding from warfarin use. Therefore thromboembolic risk assessment is required for all people with AF. Warfarin is generally considered to be underutilised * We have used the abbreviation AF to mean atrial fibrillation or flutter because the principles of antithrombotic therapy and rate control are the same for atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter. However there are some important differences. For example, achieving rate control can be more difficult in flutter than fibrillation, choice of agents for rhythm control are different and people with lone or predominant flutter should be considered for ablation therapy. Expert Review: Dr David Heaven. Consultant Cardiologist, Middlemore Hospital 6 I best practice I Issue 2 in the management of AF; it appears that approximately AF is often associated with: one-third of people with identified AF are taking warfarin. -

2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 Guideline for Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation

2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 Guideline for Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation GUIDELINES MADE SIMPLE - Focused Update Edition A Selection of Tables and Figures ACC.org/GMSAF ©2018, American College of Cardiology B18202 ©2018, American College of Cardiology 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 Guideline for Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines, and the Heart Rhythm Society Writing Committee: Craig T. January, MD, PhD, FACC, Chair L. Samuel Wann, MD, MACC, FAHA, Vice Chair Hugh Calkins, MD, FACC, FAHA, FHRS Lin Y. Chen, MD, MS, FACC, FAHA, FHRS Joaquin E. Cigarroa, MD, FACC Joseph C. Cleveland, Jr, MD, FACC Patrick T. Ellinor, MD, PhD Michael Exekowitz, MBChB, DPhil, FACC, FAHA Michael E. field, MD, FACC, FAHA, FHRS Karen Furie, MD, MPH, FAHA Paul Heidenreich, MD, FACC, FAHA Katherine T. Murray, MD, FACC, FAHA, FHRS Julie B. Shea, MS, RNCS, FHRS Cynthia M. Tracy, MD Clyde W. Yancy, MD, MACC, FAHA The purpose of the 2019 Focused Update is to update the “2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation” in areas where new evidence has emerged since its publication. The scope of this update of the 2014 AF guideline includes revisions to the section on anticoagulation due to the approval of new medications and thromboembolism protection devices, the section on catheter ablation of AF, revisions to the section on the management of AF complicating acute coronary syndrome, and new sections on device detection of AF and weight loss.