3.4 Walli Caves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cave Development in Internally Impounded Karst Masses

International Journal of Speleology 34 (1-2) 71-81 Bologna (Italy) January-July 2005 Available online at www.ijs.speleo.it International Journal of Speleology Offi cial Journal of Union Internationale de Spéléologie Partitions, Compartments and Portals: Cave Development in internally impounded karst masses R. Armstrong L. Osborne1 Re-published from: Speleogenesis and Evolution of Karst Aquifers 1 (4), www.speleogenesis.info, 12 pages (ISSN 1814-294X). Abstract: Osborne, R. A. L. 2005. Partitions, Compartments and Portals: Cave Development in internally impounded karst masses. International Journal of Speleology, 34 (1-2), 71-81. Bologna (Italy). ISSN 0392-6672. Dykes and other vertical bodies can act as aquicludes within bodies of karst rock. These partitions separate isolated bodies of soluble rock called compartments. Speleogenetically each compartment will behave as a small impounded-karst until the partition becomes breached. Breaches through partitions, portals, allow water, air and biota including humans to pass between sections of caves that were originally isolated. Keywords: impounded karst, speleogenesis in steeply dipping limestones, Australia. Received 4 June 2005; Revised 8 June 2005; Accepted 14 June 2005. INTRODUCTION It has been long recognised that bodies of karst rock may be impounded by surrounding insoluble rocks and/or confi ned by overlying aquicludes. On a smaller scale, planar bodies of insoluble rock, such as dykes, or geological structures such as faults, may act as aquicludes (partitions) within a mass of karst rock. Where swarms of dykes intrude a karst rock mass along sets of intersecting joints (or in the case of an impounded karst along parallel joints) each mass of dyke-surrounded karst rock effectively becomes a small impounded-karst (compartment) (Fig. -

The Journal of the Australian Speleological Federation Speleo

CAVES The Journal of the Australian Speleological Federation AUSTRALIA Speleo 2017: International Congress of Speleology Sydney July 2017 Bunda Cliffs • Windjana 2015 No. 202 • NOVEMBER 2016 COMING EVENTS This list covers events of interest to anyone seriously interested in caves and caves.org.au. For international events, the Chair of International Commission karst. The list is just that: if you want further information the contact details (Nicholas White, [email protected]) may have extra information. ASF for each event are included in the list for you to contact directly. The relevant A somewhat more detailed calendar was published in the recent ESpeleo. This websites and details of other international and regional events may be listed on calendar is for international events in 2016 as we have not received any infor- the UIS/IUS website www.uis-speleo.org/ or on the ASF website http://www. mation on events in Australia. 2016 November 6-13 December 12-16 International Show Caves Association Conference, Oman, http://www.i-s- American Geophysical Union, San Francisco, California, USA, http://fall- c-a.com/event/64-isca-conference meeting.agu.org/2016/ 2017 There will be neither an ASF nor an ACKMA conference in 2017. For details A very useful international calendar is posted on the Speleogenesis Network see the website https://www.speleo2017.com. The Second Circular with a lot of website at www.speleogenesis.info/directory/calendar/. Many of the meetings details is now available on the ASF and ICS websites. listed above are on it but new ones are posted regularly. -

ASF Information

Australian Speleological Federation Inc. www.caves.org.au Information Kit 2019 Australian Speleological Federation Inc. Registered as an Environmental Organisation by the Department of Environment, Canberra INFORMATION KIT January 2019 Dear Colleagues For several years the Australian Speleological Federation Inc. has been concerned about the negative image held by some cave managers and others about speleologists. We are particularly concerned that the Federation is perceived, quite incorrectly, as representing mainly the interests of recreational cavers. In fact ASF is an environmental organisation; our primary objectives relate to conservation and environmental protection, and our Constitution makes no mention of caving. The purpose of this information kit is to convey the facts relating to the contribution of the Federation and its members to protection of caves and karst in this country. Extending back over 60 years, it is an outstanding and quite unmatched record. Many new cave reserves and parks throughout Australia have been created or protected as a result of representations, lobbying and legal action by members of ASF or its member clubs, some of which would no longer be there to be managed, other than for the dedication of motivated speleologists. They have undertaken action in courts and the media to bring about a more informed public acceptance of the need for adequate protection of our caves and karst. Several have done so at immense personal cost to their finances, their career and their family life. Community honours and awards recognizing these achievements have been received in numbers quite disproportionate to our relatively small numbers. In 1973 ASF was the first organisation in the world to convene a conference specifically to discuss cave management issues, and we organised those meetings for many years until Australasian Caves and Karst Management Association Inc (ACKMA) eventually emerged. -

058 Sydney University Speleological Society

Submission No 59 INQUIRY INTO WATER AUGMENTATION Organisation: Sydney University Speleological Society Date received: 14 August 2016 Sydney University Speleological Society Submission to the Upper House Inquiry into Water Augmentation in NSW This submission is put forward on behalf of the Sydney University Speleological Society (SUSS). SUSS is the oldest caving club on mainland Australia, established in 1948, and we engage in cave surveying, scientific research, recreational caving, and karst conservation. Our aims are to foster speleology as a science and a recreational activity; to encourage the preservation of natural wilderness areas and in particular natural subterranean areas and the karst heritage of Australia; and to cooperate with other bodies in the furtherance of these aims. In accordance with this, SUSS is concerned with the proposed dam on the Belubula River in Central West NSW, specifically focusing on sections 1.b and 1.f of the Terms of Reference. A dam here is by no means a sustainable, practical or superior choice for water augmentation. Both options for the dam site (Cranky Rock and Needles Gap) would have a severe impact on the environmental, geological and cultural heritage values of the Belubula River Valley, and in particular the Cliefden Caves Area. The Cliefden Caves Area is located on the Belubula River, southwest of the City of Orange. SUSS began surveying the cave systems in 1973. This work continues, with SUSS presence at Cliefden now almost monthly. A significant part of this effort stems from the urgent need to understand and appreciate the extent and value of these systems before they may be flooded. -

6Th Australian Karst Studies Seminar

6TH AUSTRALIAN KARST STUDIES SEMINAR - Kent Henderson The sixth event in this series was held at Wellington Wellington Council which, to my mind, has proved itself Caves, New South Wales, from Friday 4 February until an exceptional cave and karst manager. Monday 4 February. The program and field trips were arranged by Mia Thurgate and Ernst Holland, with the The visit to Cathedral Cave was also interesting. It was Seminar itself organized by the Wellington Shire Council. looking as tired as ever, with its greatly out-dated It was a superbly run event, to say the least. There were infrastructure. However, its re-lighting and rehabilitation over fifty registrants, a significant number of which were is now the Council’s new No. 1 priority, and I am certain, post-graduate tertiary students. Of course, this is given its past form that once complete it rate with the generally the case, and one of the main rationales for Phosphate Mine. The afternoon finishes with a brief tour these seminars is to allow students to showcase their of Wellington Fossil Study Centre, wherein Mike Augee work in various aspects of karst science, in an informal explained recent finds and research. manner. A significant number of registrants were, coincidentally, ACKMA members. I drove up from SATURDAY, 5th FEBRUARY Melbourne in the company of ASF Vice-President Arthur Clarke, and his partner Robyn Clare, whom I’d gathered First up on Day 3 was Sue White’s offering: Models of up at Melbourne airport on my way north. We were in for speleogenesis: A review – a fascinating look at various a wonderful few days…. -

Palaeokarst Deposits in Caves: Examples from Eastern Australia and Central Europe Paleokraški Sedimenti V Jamah: Primeri Iz Vzhodne Avstralije in Srednje Evrope

COBISS: 1.01 PALAEOKARST DEPOSITS IN CAVES: EXAMPLES FROM EASTERN AUSTRALIA AND CENTRAL EUROPE PALEOKRAšKI SEDIMENTI V JAMAH: PRIMERI IZ VZHODNE AVSTRALIJE IN SREDNJE EVROPE R. Armstrong L. OSBORNE1 Abstract UDC 551.44:551.3.051(94+4) Izvleček UDK 551.44:551.3.051(94+4) R. Armstrong L. Osborne:���������������������������� Palaeokarst deposits in ca�es:���� ���Ex� R. Armstrong L. Osborne: Paleokraški sedimenti � jamah: amples from �astern Australia and Central �urope primeri iz �zhodne A�stralije in Srednje Evrope Palaeokarst deposits are most commonly found in excavations, Paleokraške sedimente največkrat najdemo v izkopih, vrtinah in drill holes and naturally exposed at the Earth’s surface. Some izdankih na zemeljskem površju. Tudi kraške jame lahko seka- caves however intersect palaeokarst deposits. This occurs in jo peleokraške sedimente. Najbolj znane po tem so velike hipo- large hypogene caves in the USA, thermal caves in Hungary gene jame v ZDA, na Madžarskem in številne jame vzhodne and in many caves in eastern Australia. Palaeokarst deposits Avstralije. Paleokraški sedimenti tako kot prikamnina tvorijo in caves respond to cave forming processes in the same way as jamske stene. V jamah najdemo različne oblike paleokraških hostrock: the palaeokarst deposits form cave walls. A range of sedimentov: zapolnjene cevi, stene iz paleokraške sige, ve- palaeokarst deposits is exposed in caves including; filled tubes, lika sedimentna telesa, cevi breče, dajke, vulkanoklastični pa- walls composed of flowstone, large-scale bodies, breccia pipes, leokras in kristalinski paleokras. Poleg tega tudi jamske skalne dykes, volcaniclastic palaeokarst and crystalline palaeokarst. oblike delno ali povsem nastajajo na paleokraških sedimentih. As well as being exposed in cave walls, palaeokarst deposits can Ti v jamah nosijo tudi zapise preteklih dogajanj, ki se drugje wholly or partly form speleogens (speleogens made from pal- niso ohranili, a je te zapise velikokrat težko povezati z osta- aeokarst). -

The Journal of the Australian Speleological Federation Ningaloo Underground Saving Cliefden Caves Elery Hamilton-Smith No

CAVES The Journal of the Australian Speleological Federation AUSTRALIA Ningaloo Underground Saving Cliefden Caves Elery Hamilton-Smith No. 201 • SEPTEMBER 2015 COMING EVENTS This list covers events of interest to anyone seriously interested in caves and (Nicholas White, [email protected]) may have extra information. karst. The list is just that: if you want further information the contact details However, this calendar is not all events; just some of the main ones. A much ASF for each event are included in the list for you to contact directly. The relevant more detailed calendar was published in the most recenr ESpeleo. We do not websites and details of other international and regional events may be listed on seem to have any events advertised in Australia for the rest of 2015, only the the UIS/IUS website www.uis-speleo.org/ or on the ASF website http://www. ASF Council meeting in early January 2016, probably in Sydney. Details of the caves.org.au. For international events, the Chair of International Commission Council Meeting will be sent out to clubs later this year. 2015 September 7-10 October 20-23 Natural History of the Belubula Valley including the Cliefden Caves and 2nd International Planetary Caves Conference, Flagstaff, Arizona, USA. Fossil Hill Linnean Society of NSW Symposium Bathurst, NSW. A sympo- Details on: http://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/2ndcaves2015/ sium to explain, interpret and review recent scientific research on geology, November 1-4 palaeontology, botany, zoology, and speleology of the caves and karst. Details Geological Society of America (GSA) Convention, Baltimore, Maryland available on the Linnean Society NSW website nsw.org.au//symposia/sym- USA. -

Cliefden Caves Reference List 2

CLIEFDEN CAVES REFERENCE LIST AUTHOR/S DATE TITLE PUB TOPIC 1 ADAMSON, C.L. & TRUEMAN, N.A. 1962 Geology of the Cranky Rock and Needles New South Wales Geological Survey Reports 11 GEOLOGY, DAM SITES proposed dam storage areas 2 ANDERSON, C. 1924 Visit to Belubula Caves Australian Museum Magazine 2(1):12-17 DESCRIPTION 3 ANON 1967 Search and rescue practice-Cliefden Australian Speleological Federation Newsletter 36:5 CAVE RESCUE 4 BEIR, M., 1967 Some cave-dwelling Pseudoscorpioneda from Records of the South Australian Museum 15(5): 757-765 PSEUDOSCORPIONS Australia and New Caledonia 5 BOYD, G.L., 1970 A comparative study of three proposed dam Kensington, University of New South Wales, BSc (Applied GEOLOGY, DAM SITES sites, Central Western N.S.W. Geology) Honours thesis unpubl. 6 CAMERON-SMITH, B., 1977 Cave management in New South Wales National Cave Management in Australia II, Proceedings of the Second CAVE MANAGEMENT Parks Australian Conference on Cave Tourism and Management : 13- 25. 7 CARNE, J.E. & JONES, L.J., 1919 The limestone deposits of New South Wales Mineral Resources, Geological Survey of New South Wales 25 LIMESTONE 8 CARTHEW, K.D. & DRYSDALE, R.N. 2003 Late Holocene fluvial change in a tufa depositing Australian Geographer 34( 1), 123–139. DAVYS CREEK TUFA stream: Davys Creek, New South Wales, Australia 9 DRYSDALE, R., LUCAS, S. & CARTHEW, The influence of diurnal temperatures on the Hydrological Processes 17: 3421–3441. DAVYS CREEK TUFA K. hydrochemistry of a tufa-depositing stream 10 ETHRIDGE, R. jr 1895 On the occurrence of a stromatoporoid, allied to Records of the Geological Survey of New South Wales 4: 134- INVERTEBRATE PALAEONTOLOGY Labechia and Rosenella , in Siluro-Devonian 140. -

Journal of Cave and Karst Studies

September 2020 Volume 82, Number 3 JOURNAL OF ISSN 1090-6924 A Publication of the National CAVE AND KARST Speleological Society STUDIES DEDICATED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF SCIENCE, EDUCATION, EXPLORATION, AND CONSERVATION Published By BOARD OF EDITORS The National Speleological Society Anthropology George Crothers http://caves.org/pub/journal University of Kentucky Lexington, KY Office [email protected] 6001 Pulaski Pike NW Huntsville, AL 35810 USA Conservation-Life Sciences Julian J. Lewis & Salisa L. Lewis Tel:256-852-1300 Lewis & Associates, LLC. [email protected] Borden, IN [email protected] Editor-in-Chief Earth Sciences Benjamin Schwartz Malcolm S. Field Texas State University National Center of Environmental San Marcos, TX Assessment (8623P) [email protected] Office of Research and Development U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Leslie A. North 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, KY Washington, DC 20460-0001 [email protected] 703-347-8601 Voice 703-347-8692 Fax [email protected] Mario Parise University Aldo Moro Production Editor Bari, Italy [email protected] Scott A. Engel Knoxville, TN Carol Wicks 225-281-3914 Louisiana State University [email protected] Baton Rouge, LA [email protected] Exploration Paul Burger National Park Service Eagle River, Alaska [email protected] Microbiology Kathleen H. Lavoie State University of New York Plattsburgh, NY [email protected] Paleontology Greg McDonald National Park Service Fort Collins, CO The Journal of Cave and Karst Studies , ISSN 1090-6924, CPM [email protected] Number #40065056, is a multi-disciplinary, refereed journal pub- lished four times a year by the National Speleological Society. -

Studies on Aragonite and Its Occurrence in Caves, Including New South Wales Caves

i i “Main” — 2006/8/13 — 12:21 — page 123 — #27 i i Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, Vol. 137, p. 123–149, 2004 ISSN 0035-9173/04/0200123–27 $4.00/1 Studies on Aragonite and its Occurrence in Caves, including New South Wales Caves jill rowling Abstract: Aragonite is a minor secondary mineral in many limestone caves throughout the world and is probably the second-most common cave mineral after calcite. It occurs in the vadose zone of some caves in New South Wales. Aragonite is unstable in fresh water and usually reverts to calcite, but it is actively depositing in some NSW caves. A review of the cave aragonite problem showed that chemical inhibitors to calcite deposition assist in the precipitation of calcium carbonate as aragonite instead of calcite. Chemical inhibitors physically block the positions on the calcite crystal lattice which otherwise would develop into a larger crystal. Often an inhibitor for calcite has no effect on the aragonite crystal lattice, thus favouring aragonite depositition. Several factors are associated with the deposition of aragonite instead of calcite speleothems in NSW caves. They included the presence of ferroan dolomite, calcite-inhibitors (in particular ions of magnesium, manganese, phosphate, sulfate and heavy metals), and both air movement and humidity. Keywords: aragonite, cave minerals, calcite, New South Wales INTRODUCTION (Figure 1). It has one cleavage plane {010} (across the “steeples”) while calcite has a per- Aragonite is a polymorph of calcium carbon- fect cleavage plane {1011¯ } producing angles ◦ ◦ ate, CaCO3. It was named after the province of 75 and 105 . -

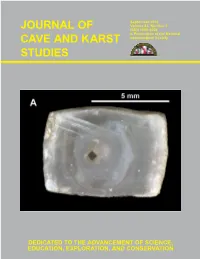

Chromophores Producing Blue Speleothems at Cliefden, NSW

Helictite (2002) 38(1): pp. 3-6. Chromophores Producing Blue Speleothems at Cliefden, NSW. Ken Turner. “Elken Ridge”, RMB 9 Bicton Lane, CUMNOCK NSW 2867 [email protected]. Abstract Osborne (1978) has described in some detail the blue stalactites that occur in Murder and Boonderoo Caves at Cliefden, NSW and reports “that the colour is due to some impurity in the aragonite and not to refractive effects”. In this study, small samples from the Boonderoo and Taplow Maze blue speleothems have been chemically analysed. Based on these chemical analyses it is suggested that the major chromophore is copper, with secondary contributions from chromium (Taplow Maze only) and perhaps nickel. INTRODUCTION Blue speleothems occur in Murder (CL2), Boonderoo (CL3) and Taplow Maze (CL5) Caves in the Cliefden Karst area in Central Western NSW (Figure 1). The caves are located in the Belubula River valley about 30 km north east of Cowra. The sky-blue stalactites (Figure 2) in Murder and Boonderoo Caves are reported to occur at the boundaries of the Upper and Lower Units of the Boonderoo Limestone Member and the Boonderoo and Large Flat Limestone Members respectively (Osborne, 1978). Osborne examined an Australian Museum sample (specimen number D36380) of the Boonderoo blue stalactite using optical microscopy and X-ray Figure 1: Location of Boonderoo, Murder and Taplow powder diffraction and found that the stalactite consisted Maze Caves and nearby abandoned Barite Mine. of an inner zone of sparry calcite and an outer zone of aragonite. The author further concluded that “the blue baseline compositional data, samples of adjacent white colour is due to some impurity in the aragonite”. -

CLIEFDEN CAVES, NEW SOUTH WALES, AUSTRALIA: UNDER REAL DAM THREAT Garry K

REPORT CLIEFDEN CAVES, NEW SOUTH WALES, AUSTRALIA: UNDER REAL DAM THREAT Garry K. Smith President - Newcastle and Hunter Valley Speleological Society Brief Overview The Cliefden Caves are located on the Belubula River, New South Wales, between the towns of Carcoar and Canowindra. There are in excess of 60 caves and over 50 additional karst features at Cliefden and evidence suggests that they are hypogene caves (formed by rising ground water). A permanent thermal spring is situated immediately downstream of the limestone outcropping and may have played a part in this process. (Osborne, R.A.L., 2001 & 2009) The caves consist of extensive underground caverns and networks of passages up to three kilometres in length. The Cliefden limestone was the first discovered in Australia, by surveyor George Evans on 24 May 1815. (Evans, G.W., 1815) Surveyor, John Oxley in 1817, set out from Bathurst on an expedition to solve 'The Mystery of the Western Rivers'. On the first leg of his exploration he travelled down the Belubula River and Just a small portion of the outstanding helictite display camped in the vicinity of Cliefden downstream from in Main Cave - Cliefden. Limestone Creek. (Oxley, J., 1820) Photo: Garry K Smith The early European history of the area also includes the Rothery family (property owners of Cliefden since 1831) heritage, scientific value, cave fauna (including being held up by the notorious bushrangers Ben Hall’s threatened bat species), fossils, geology, geomorphology gang in 1863. (White C. 1903) and paleontology to name a few. The Belubula River also supports a population of platypus and native fish Geologists from around the world regard the Fossil Hill species including the threatened Murray Cod.