Navigating Great Power Competition in Southeast Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater China: the Next Economic Superpower?

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Murray Weidenbaum Publications Government, and Public Policy Contemporary Issues Series 57 2-1-1993 Greater China: The Next Economic Superpower? Murray L. Weidenbaum Washington University in St Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers Part of the Economics Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Weidenbaum, Murray L., "Greater China: The Next Economic Superpower?", Contemporary Issues Series 57, 1993, doi:10.7936/K7DB7ZZ6. Murray Weidenbaum Publications, https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers/25. Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy — Washington University in St. Louis Campus Box 1027, St. Louis, MO 63130. Other titles available in this series: 46. The Seeds ofEntrepreneurship, Dwight Lee Greater China: The 47. Capital Mobility: Challenges for Next Economic Superpower? Business and Government, Richard B. McKenzie and Dwight Lee Murray Weidenbaum 48. Business Responsibility in a World of Global Competition, I James B. Burnham 49. Small Wars, Big Defense: Living in a World ofLower Tensions, Murray Weidenbaum 50. "Earth Summit": UN Spectacle with a Cast of Thousands, Murray Weidenbaum Contemporary 51. Fiscal Pollution and the Case Issues Series 57 for Congressional Term Limits, Dwight Lee February 1993 53. Global Warming Research: Learning from NAPAP 's Mistakes, Edward S. Rubin 54. The Case for Taxing Consumption, Murray Weidenbaum 55. Japan's Growing Influence in Asia: Implications for U.S. Business, Steven B. Schlossstein 56. The Mirage of Sustainable Development, Thomas J. DiLorenzo Additional copies are available from: i Center for the Study of American Business Washington University CS1- Campus Box 1208 One Brookings Drive Center for the Study of St. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

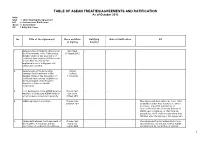

Table of Asean Treaties/Agreements And

TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. Title of the Agreement Place and Date Ratifying Date of Ratification EIF of Signing Country 1. Memorandum of Understanding among Siem Reap - - - the Governments of the Participating 29 August 2012 Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Second Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self- Certification System 2. Memorandum of Understanding Phuket - - - between the Government of the Thailand Member States of the Association of 6 July 2012 Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Health Cooperation 3. Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Phnom Penh - - - Ministers on Enhancing ASEAN Unity for Cambodia a Harmonised and Secure Community 29 May 2012 4. ASEAN Agreement on Custom Phnom Penh - - - This Agreement shall enter into force, after 30 March 2012 all Member States have notified or, where necessary, deposited instruments of ratifications with the Secretary General of ASEAN upon completion of their internal procedures, which shall not take more than 180 days after the signing of this Agreement 5. Agreement between the Government of Phnom Penh - - - The Agreement has not entered into force the Republic of Indonesia and the Cambodia since Indonesia has not yet notified ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2 April 2012 Secretariat of its completion of internal 1 TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. -

Major Powers and Global Contenders

CHAPTER 2 Major Powers and Global Contenders A great number of historians and political scientists share the view that international relations cannot be well understood without paying attention to those states capable of making a difference. Most diplo- matic histories are largely histories of major powers as represented in modern classics such as A. J. P. Taylor’s The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, 1848–1918, or Paul Kennedy’s The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. In political science, the main theories of international relations are essentially theories of major power behavior. The realist tradition, until recently a single paradigm in the study of international relations (Vasquez 1983), is based on the core assumptions of Morgenthau’s (1948) balance-of-power theory about major power behavior. As one leading neorealist scholar stated, “a general theory of international politics is necessarily based on the great powers” (Waltz 1979, 73). Consequently, major debates on the causes of war are centered on assumptions related to major power behavior. Past and present evidence also lends strong support for continuing interest in the major powers. Historically, the great powers partici- pated in the largest percentage of wars in the last two centuries (Wright 1942, 1:220–23; Bremer 1980, 79; Small and Singer 1982, 180). Besides wars, they also had the highest rate of involvement in international crises (Maoz 1982, 55). It is a compelling record for the modern history of warfare (since the Napoleonic Wars) that major powers have been involved in over half of all militarized disputes, including those that escalated into wars (Gochman and Maoz 1984, 596). -

Assessing Investment Policies of Member Countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council

ASSESSING INVESTMENT POLICIES OF MEMBER COUNTRIES OF THE GULF COOPERATION COUNCIL Stocktaking analysis prepared by the MENA-OECD Investment Programme and presented at the Conference entitled: “Assessing Investment Policies of GCC Countries: Translating economic diversification strategies into sound international investment policies” On 5 April 2011 in Abu Dhabi Organised in co-operation of and hosted by the Ministry of Economy of the United Arab Emirates 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. INTRODUCTION: ECONOMIC AND FDI OVERVIEW AND DIVERSIFICATION POLICIES ................. 7 1. After an eventful decade, the GCC economies are at a crossroads ....................................... 7 2. Diversification remains a key challenge in the GCC ............................................................... 9 3. The GCC needs to address human capital issues ................................................................. 17 II. PRESENTATION OF THE ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY .......................................................... 21 1. The BCDS methodology ........................................................................................................ 21 2. The BCDS investment policy dimension and the stocktaking study .................................... 22 III. ASSESSMENT OF INVESTMENT POLICIES – FDI LAW AND POLICY OF GCC COUNTRIES ........ 24 1. Restrictions to National Treatment ..................................................................................... -

China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States

Order Code RL32688 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Updated April 4, 2006 Bruce Vaughn (Coordinator) Analyst in Southeast and South Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Wayne M. Morrison Specialist in International Trade and Finance Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Summary Southeast Asia has been considered by some to be a region of relatively low priority in U.S. foreign and security policy. The war against terror has changed that and brought renewed U.S. attention to Southeast Asia, especially to countries afflicted by Islamic radicalism. To some, this renewed focus, driven by the war against terror, has come at the expense of attention to other key regional issues such as China’s rapidly expanding engagement with the region. Some fear that rising Chinese influence in Southeast Asia has come at the expense of U.S. ties with the region, while others view Beijing’s increasing regional influence as largely a natural consequence of China’s economic dynamism. China’s developing relationship with Southeast Asia is undergoing a significant shift. This will likely have implications for United States’ interests in the region. While the United States has been focused on Iraq and Afghanistan, China has been evolving its external engagement with its neighbors, particularly in Southeast Asia. In the 1990s, China was perceived as a threat to its Southeast Asian neighbors in part due to its conflicting territorial claims over the South China Sea and past support of communist insurgency. -

Earth Moves U.S

Earth moves U.S. GOVERNMENTWORLD ™ GEOGRAPHYHISTORY from the Esri GeoInquiries collection for World Geography Target audience – World geography learners Time required – 15 minutes Activity Examine seismic and volcanic activity patterns around the world relative to tectonic plate boundaries, physical features on the earth’s surface, and cities at risk. World Geography C3:D2.Geo.1.6-8. Construct maps to represent and explain the spatial patterns of cultural Standards and environmental characteristics. Learning Outcomes • Locate zones of significant seismic or volcanic activity. • Describe the relationship between zones of high seismic or volcanic activity and tectonic plate boundaries. Map URL: http://esriurl.com/worldGeoInquiry3 Ask Where are global earthquakes located? ʅ Click the link above to launch the map. ʅ Examine the yellow dots on the map that represent earthquakes with a magnitude of 5.7+. ? What patterns do you see on the map? [Answers will vary. Many earthquakes occur on the western coast of North and South America, along the eastern coast of Asia, and along the islands of the Pacific Rim. The pattern follows the Ring of Fire. Earthquakes occur in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.] Acquire Where are the largest earthquakes on Earth? ʅ With the Details button depressed, click the button, Show Contents. ʅ Click the Earthquakes Magnitude 5.7+ layer name, and then click the Show Table button. – Each record in this table represents one point on the map. ʅ Click the Magnitude column heading (field) and choose Sort Descending. ʅ Highlight the first 20 records (highest magnitude earthquakes). (See the Select Features in a Table ToolTip on the next page for details.) ? Where are the blue highlighted high-magnitude earthquakes located on the map? [Mostly in the Ring of Fire, Southeast Asia, and west coast of South America] Explore Where are the active volcanoes on Earth? ʅ In the top-right corner of the table, click the X to close the table. -

Asean Charter

THE ASEAN CHARTER THE ASEAN CHARTER Association of Southeast Asian Nations The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established on 8 August 1967. The Member States of the Association are Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. The ASEAN Secretariat is based in Jakarta, Indonesia. =or inquiries, contact: Public Affairs Office The ASEAN Secretariat 70A Jalan Sisingamangaraja Jakarta 12110 Indonesia Phone : (62 21) 724-3372, 726-2991 =ax : (62 21) 739-8234, 724-3504 E-mail: [email protected] General information on ASEAN appears on-line at the ASEAN Website: www.asean.org Catalogue-in-Publication Data The ASEAN Charter Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, January 2008 ii, 54p, 10.5 x 15 cm. 341.3759 1. ASEAN - Organisation 2. ASEAN - Treaties - Charter ISBN 978-979-3496-62-7 =irst published: December 2007 1st Reprint: January 2008 Printed in Indonesia The text of this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted with proper acknowledgment. Copyright ASEAN Secretariat 2008 All rights reserved CHARTER O THE ASSOCIATION O SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS PREAMBLE WE, THE PEOPLES of the Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), as represented by the Heads of State or Government of Brunei Darussalam, the Kingdom of Cambodia, the Republic of Indonesia, the Lao Peoples Democratic Republic, Malaysia, the Union of Myanmar, the Republic of the Philippines, the Republic of Singapore, the Kingdom of Thailand and the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam: NOTING -

Australia and the Origins of ASEAN (1967–1975)

1 Australia and the origins of ASEAN (1967–1975) The origins of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and of Australia’s relations with it are bound up in the period of the Cold War in East Asia from the late 1940s, and the serious internal and inter-state conflicts that developed in Southeast Asia in the 1950s and early 1960s. Vietnam and Laos were engulfed in internal wars with external involvement, and conflict ultimately spread to Cambodia. Further conflicts revolved around Indonesia’s unstable internal political order and its opposition to Britain’s efforts to secure the positions of its colonial territories in the region by fostering a federation that could include Malaya, Singapore and the states of North Borneo. The Federation of Malaysia was inaugurated in September 1963, but Singapore was forced to depart in August 1965 and became a separate state. ASEAN was established in August 1967 in an effort to ameliorate the serious tensions among the states that formed it, and to make a contribution towards a more stable regional environment. Australia was intensely interested in all these developments. To discuss these issues, this chapter covers in turn the background to the emergence of interest in regional cooperation in Southeast Asia after the Second World War, the period of Indonesia’s Konfrontasi of Malaysia, the formation of ASEAN and the inauguration of multilateral relations with ASEAN in 1974 by Gough Whitlam’s government, and Australia’s early interactions with ASEAN in the period 1974‒75. 7 ENGAGING THE NEIGHBOURS The Cold War era and early approaches towards regional cooperation The conception of ‘Southeast Asia’ as a distinct region in which states might wish to engage in regional cooperation emerged in an environment of international conflict and the end of the era of Western colonialism.1 Extensive communication and interactions developed in the pre-colonial era, but these were disrupted thoroughly by the arrival of Western powers. -

Zones of Interest: the Fault Lines of Contemporary Great Power Conflict

Zones of Interest: The Fault Lines of Contemporary Great Power Conflict Ronald M. Behringer Department of Political Science Concordia University May 2009 Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association, Ottawa, Ontario, May 27-29, 2009. Please e-mail any comments to [email protected]. Abstract Each of the contemporary great powers—the United States, Russia, China, the United Kingdom, and France—has a history of demarcating particular regions of the world as belonging to their own sphere of influence. During the Cold War, proponents of the realist approach to international relations argued that the United States and the Soviet Union could preserve global peace by maintaining separate spheres of influence, regions where they would sustain order and fulfill their national interest without interference from the other superpower. While the great powers used to enjoy unbridled primacy within their spheres of influence, changes in the structures of international governance— namely the end of the imperial and Cold War eras—have led to a sharp reduction in the degree to which the great powers have been able to dominate other states within these spheres. In this paper, I argue that while geopolitics remains of paramount importance to the great powers, their traditional preoccupation with spheres of influence has been replaced with their prioritization of “zones of interest”. I perform a qualitative analysis of the zones of interest of the five great powers, defined as spatial areas which have variable geographical boundaries, but are distinctly characterized by their military, economic, and/or cultural importance to the great powers. -

Global Shifts in Power and Geopolitical Regionalization

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Scholvin, Sören Working Paper Emerging Non-OECD Countries: Global Shifts in Power and Geopolitical Regionalization GIGA Working Papers, No. 128 Provided in Cooperation with: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies Suggested Citation: Scholvin, Sören (2010) : Emerging Non-OECD Countries: Global Shifts in Power and Geopolitical Regionalization, GIGA Working Papers, No. 128, German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/47796 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Inclusion of a paper in the Working Papers series does not constitute publication and should not limit publication in any other venue. -

Pan-Asianism As an Ideal of Asian Identity and Solidarity, 1850–Present アジアの主体性・団結の理想としての汎アジア主 義−−1850年から今日まで

Volume 9 | Issue 17 | Number 1 | Article ID 3519 | Apr 25, 2011 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Pan-Asianism as an Ideal of Asian Identity and Solidarity, 1850–Present アジアの主体性・団結の理想としての汎アジア主 義−−1850年から今日まで Christopher W. A. Szpilman, Sven Saaler Pan-Asianism as an Ideal of Asian Attempts to define Asia are almost as old as the Identity and Solidarity,term itself. The word “Asia” originated in ancient Greece in the fifth century BC. It 1850–Present originally denoted the lands of the Persian Empire extending east of the Bosphorus Straits Sven Saaler and Christopher W. A. but subsequently developed into a general term Szpilman used by Europeans to describe all the lands lying to the east of Europe. (The point where This is a revised, updated and abbreviated Europe ended and Asia began was, however, version of the introduction to the two volume never clearly defined.) Often, this usage collection by the authors ofPan-Asianism. A connoted a threat, real or perceived, by Asia to Documentary History Vol. 1 covers the years Europe—a region smaller in area, much less 1850-1920; Vol. 2 covers the years 1850- populous, poorer, and far less significant than present, link. Asia in terms of global history. The economic and political power of Asia, the The term “Asia” arrived in East Asia relatively world’s largest continent, is increasing rapidly. late, being introduced by Jesuit missionaries in According to the latest projections, the gross the sixteenth century. The term is found, domestic products of China and India, the written in Chinese characters 亜細亜( ), on world’s most populous nations, will each Chinese maps of the world made around 1600 surpass that of the United States in the not-too- under the supervision of Matteo Ricci distant future.