Minidisc Recorders Versus Audiocassette Recorders: a Performance Comparison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tools for Digital Audio Recording in Qualitative Research

Sociology at Surrey University of Surrey social researchUPDATE • The technology needed to make digital recordings of interviews and meetings for the purpose of qualitative research is described. • The advantages of using digital audio technology are outlined. • The technical background needed to make an informed choice of technology is summarised. • The Update concludes with brief evaluations of the types of audio recorder currently available. Tools for Digital Audio Recording in Qualitative Research Alan Stockdale In a recent book Michael Patton writes, “As a naïveté, can heighten the sense of “being Dr. Stockdaleʼs training is in good hammer is essential to fine carpentry, there”. For discussion of the naturalization cultural anthropology. He is a a good tape recorder is indispensable to of audio recordings in qualitative research, senior research associate at fine fieldwork” (Patton 2002: 380). He see Ashmore and Reed (2000). Education Development Center goes on to cite an example of transcribers in Boston, Massachusetts, at one university who estimated that 20% Why digital? of the tapes given to them “were so badly where he currently serves Audio Quality as an investigator on several recorded as to be impossible to transcribe The recording process used to make genetics education research accurately – or at all.” Surprisingly there analogue recordings using cassette tape is remarkably little discussion of tools and introduces noise, particularly tape hiss. projects funded by the U.S. techniques for recording interviews in the Noise can drown out softly spoken words National Institutes of Health. qualitative research literature (but see, for and makes transcription of normal speech example, Modaff and Modaff 2000). -

How to Tape-Record Primate Vocalisations Version June 2001

How To Tape-Record Primate Vocalisations Version June 2001 Thomas Geissmann Institute of Zoology, Tierärztliche Hochschule Hannover, D-30559 Hannover, Germany E-mail: [email protected] Key Words: Sound, vocalisation, song, call, tape-recorder, microphone Clarence R. Carpenter at Doi Dao (north of Chiengmai, Thailand) in 1937, with the parabolic reflector which was used for making the first sound- recordings of wild gibbons (from Carpenter, 1940, p. 26). Introduction Ornithologists have been exploring the possibilities and the methodology of tape- recording and archiving animal sounds for many decades. Primatologists, however, have only recently become aware that tape-recordings of primate sound may be just as valuable as traditional scientific specimens such as skins or skeletons, and should be preserved for posterity. Audio recordings should be fully documented, archived and curated to ensure proper care and accessibility. As natural populations disappear, sound archives will become increasingly important. This is an introductory text on how to tape-record primate vocalisations. It provides some information on the advantages and disadvantages of various types of equipment, and gives some tips for better recordings of primate vocalizations, both in the field and in the zoo. Ornithologists studying bird sound have to deal with very similar problems, and their introductory texts are recommended for further study (e.g. Budney & Grotke 1997; © Thomas Geissmann Geissmann: How to Tape-Record Primate Vocalisations 2 Kroodsman et al. 1996). For further information see also the websites listed at the end of this article. As a rule, prices for sound equipment go up over the years. Prices for equipment discussed below are in US$ and should only be used as very rough estimates. -

The Sound Effect

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright The Sound Effect: a Study in Radical Sound Design Ian Robert Stevenson A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Architecture, Design & Planning The University of Sydney 2015 ABSTRACT ABSTRACT This research project combines a theoretical intervention into sound ontology, with an empirical investigation into listening experience, in parallel with two technologically focused, research-led creative practice projects. -

The Nature and Practice of Soundscape Composition Bob Gluck, November 1999

1 The Nature and Practice of Soundscape Composition Bob Gluck, November 1999 Soundscapes first emerged as a musical genre in the 1970s. They represent a unique musical form that grew out of the encounter between electronic music and acoustic ecology. Its driving force has been Canadian composers and sound artists. Soundscapes would not be conceivable outside of the history and context of electronic music. It was within the latter field that musicians and thinkers extended the boundaries of what constitutes musical sound, as Joel Chadabe (1997) terms it "the great opening up of music to all sounds." Soundscapes also reflect a particular historical moment. Its materials, forms and the relationship between the two (Adorno, 1996) offer a musical commentary on issues arising in the late 20th century western world. Acoustic ecology and soundscapes, a brief introduction The figure most identified as founding the acoustic ecology movement, from which soundscapes sprung forth, is R. Murray Schaefer. Schaefer wrote (1977, 1994): "I call the acoustic environment the soundscape, by which I mean the total field of sounds wherever we are. It is a word derived from landscape, though, unlike it, not strictly limited to the outdoors." Schaefer founded what has become known as the World Soundscape Project (WSP), which has been described by fellow founding member Barry Truax (1995), as: "to document and archive soundscapes, to describe and analyze them, and to promote increased public awareness through listening and critical thinking" and "to re-design -

Compact Disc Minidisc Deck

3-856-489-32(1) Compact Disc MiniDisc Deck Operating Instructions EN GB Mode d’emploi F f MXD-D1 1996 by Sony Corporation Sony Corporation Printed in Japan On cleaning WARNING Precautions Clean the cabinet, panel and controls with a soft cloth slightly moistened with To prevent fire or shock a mild detergent solution. Do not use On safety any type of abrasive pad, scouring hazard, do not expose the unit Should any solid object or liquid fall powder or solvent such as alcohol or to rain or moisture. into the cabinet, unplug the unit and benzine. To avoid electrical shock, do have it checked by qualified personnel before operating it any further. If you have any questions or problems not open the cabinet. Refer concerning your unit, please consult your nearest Sony dealer. servicing to qualified On power sources personnel only. • Before operating the unit, check that the operating voltage of the unit is identical with your local power The laser component in this product is supply. The operating voltage is capable of emitting radiation exceeding the limit for Class 1. indicated on the nameplate at the rear of the unit. • If you are not going to use the unit for a long time, be sure to disconnect the CAUTION unit from the wall outlet. To TO PREVENT ELECTRIC SHOCK, DO disconnect the AC power cord, grasp NOT USE THIS POLARIZED AC PLUG the plug itself; never pull the cord. WITH AN EXTENSION CORD, RECEPTACLE OR OTHER OUTLET UNLESS THE BLADES CAN BE FULLY On condensation in the unit INSERTED TO PREVENT BLADE If the unit is brought directly from a EXPOSURE. -

Field Recording, Technology and Creative Listening Jean-Baptiste Masson

Field Recording, Technology and Creative Listening Jean-Baptiste Masson To cite this version: Jean-Baptiste Masson. Field Recording, Technology and Creative Listening. Proceedings of the 4th International Congress on Ambiances, Alloaesthesia: Senses, Inventions, Worlds, Réseau International Ambiances, Dec 2020, e-conference, France. pp. 226-230, 10.48537/hal-03220325. hal-03220325 HAL Id: hal-03220325 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03220325 Submitted on 14 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 226 Field Recording, Technology and Creative Listening Abstract. While more and more used in music Field Recording, and sound art, field recording remains under Technology theorised. This paper aims to study this practice in relation to the technology and to and Creative modes of listening. I argue that field recording cannot be thought without its technological Listening tools: microphones, headphones, recorders and speakers. I discuss that this set of audio technologies acts as a way of ‘translating’ the environment by allowing for a detachment toward what is listened to. I also conceptualise listening as a creative stance. To support my claim, I deploy historical examples from the sound hunting movement alongside recent scholarly works that investigate the role of imagination and empathy in music extending this method to ambient sounds. -

MINIDISC MANUAL V3.0E Table of Contents

MINIDISC MANUAL V3.0E Table of Contents Introduction . 1 1. The MiniDisc System 1.1. The Features . 2 1.2. What it is and How it Works . 3 1.3. Serial Copy Management System . 8 1.4. Additional Features of the Premastered MD . 8 2. The production process of the premastered MD 2.1. MD Production . 9 2.2. MD Components . 10 3. Input components specification 3.1. Sound Carrier Specifications . 12 3.2. Additional TOC Data / Character Information . 17 3.3. Label-, Artwork- and Print Films . 19 3.4. MiniDisc Logo . 23 4. Sony DADC Austria AG 4.1. The Company . 25 5. Appendix Form Sheets Introduction T he quick random access of Compact Disc players has become a necessity for music lovers. The high quality of digital sound is now the norm. The future of personal audio must meet the above criteria and more. That’s why Sony has created the MiniDisc, a revolutionary evolution in the field of digital audio based on an advanced miniature optical disc. The MD offers consumers the quick random access, durability and high sound quality of optical media, as well as superb compactness, shock- resistant portability and recordability. In short, the MD format has been created to meet the needs of personal music entertainment in the future. Based on a dazzling array of new technologies, the MiniDisc offers a new lifestyle in personal audio enjoyment. The Features 1. The MiniDisc System 1.1. The Features With the MiniDisc, Sony has created a revolutionary optical disc. It offers all the features that music fans have been waiting for. -

The Concrete 'Sound Object' and the Emergence of Acoustical

transcultural studies 13 (2017) 239-263 brill.com/ts The Concrete ‘Sound Object’ and the Emergence of Acoustical Film and Radiophonic Art in the Modernist Avant-Garde Christopher Williams University of Technology, Sydney [email protected] Abstract Radiophonic art could not have emerged at the end of the 1920s without an intense period of experimentation across the creative fields of radio, new music, phonogra- phy, film, literature and theatre. The engagement with sound recording and broadcast technologies by artists radically expanded the scope of creative possibility within their respective practices, and more particularly, pointed to new forms of (inter-)artistic practice based in sound technologies including those of radio. This paper examines the convergence of industry, the development of technology, and creative practice that gave sound, previously understood as immaterial, a concrete objectification capable of responding to creative praxis, and so brought about the conditions that enabled a radiophonic art to materialize. Keywords radiophonic – radio – montage – Walter Ruttmann – constructivism – Grammophonmusik – Lehrstück – Dziga Vertov Absolute Beginnings It is no accident that the historical conditions that enabled the emergence of a radiophonic art intersected in Germany during the Weimar Republic, following the successful attempt to stabilize the economy previously ravaged by hyper- inflation. John Willett emphasizes the ethos of internationalism, collectivism, and a belief in the transformative -

AW2400 Owner's Manual

Owner’s Manual EN FCC INFORMATION (U.S.A.) 1. IMPORTANT NOTICE: DO NOT MODIFY THIS devices. Compliance with FCC regulations does not guar- UNIT! antee that interference will not occur in all installations. If This product, when installed as indicated in the instruc- this product is found to be the source of interference, tions contained in this manual, meets FCC requirements. which can be determined by turning the unit “OFF” and Modifications not expressly approved by Yamaha may “ON”, please try to eliminate the problem by using one of void your authority, granted by the FCC, to use the prod- the following measures: uct. Relocate either this product or the device that is being 2. IMPORTANT: When connecting this product to acces- affected by the interference. sories and/or another product use only high quality Utilize power outlets that are on different branch (circuit shielded cables. Cable/s supplied with this product MUST breaker or fuse) circuits or install AC line filter/s. be used. Follow all installation instructions. Failure to fol- In the case of radio or TV interference, relocate/reorient low instructions could void your FCC authorization to use the antenna. If the antenna lead-in is 300 ohm ribbon this product in the USA. lead, change the lead-in to co-axial type cable. 3. NOTE: This product has been tested and found to com- If these corrective measures do not produce satisfactory ply with the requirements listed in FCC Regulations, Part results, please contact the local retailer authorized to dis- 15 for Class “B” digital devices. -

7-IN-1 TURNTABLE Important Safety Instructions

MODEL: VTA-204B 7-IN-1 TURNTABLE Important Safety Instructions......................................................................................................................... 3 Product Overview .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Setup / Basic Operation................................................................................................................................. 7 Listening to a Vinyl Record ............................................................................................................................ 7 Listening to a CD ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Listening to the FM Radio.............................................................................................................................. 9 Listening to an External Audio Device (AUX Mode) ...................................................................................... 9 Listening to an External Audio Device (Bluetooth Mode) ............................................................................ 10 Listening to a Cassette Tape ....................................................................................................................... 10 USB Recording Operation........................................................................................................................... 10 Maintenance / Proper -

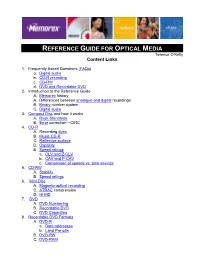

REFERENCE GUIDE for OPTICAL MEDIA Terence O’Kelly Content Links

REFERENCE GUIDE FOR OPTICAL MEDIA Terence O’Kelly Content Links 1. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) a. Digital audio b. CD-R recording c. CD-RW d. DVD and Recordable DVD 2. Introduction to the Reference Guide A. Memorex history A. Differences between analogue and digital recordings B. Binary number system C. Digital audio 3. Compact Disc and how it works A. Book Standards B. Error correction—CIRC 4. CD-R A. Recording dyes B. Music CD-R C. Reflective surface D. Capacity E. Speed ratings a. CLV and Z-CLV b. CAV and P-CAV c. Comparison of speeds vs. time savings 5. CD-RW A. Stability B. Speed ratings 6. Mini-Disc A. Magneto-optical recording C. ATRAC compression D. Hi-MD 7. DVD A. DVD Numbering B. Recordable DVD C. DVD Capacities 8. Recordable DVD Formats A. DVD-R a. Data addresses b. Land Pre-pits B. DVD-RW C. DVD-RAM a. Data addresses b. Cartridge types D. DVD+R a. Data addresses b. ADIP E. DVD+RW 9. Recording onto DVD discs A. VR Recording onto DVD--+VR and –VR B. CPRM C. Capacities of recordable DVD discs a. Capacities in terms of time b. Set-top recorder time chart D. Double-Layer Discs E. Recording Speeds 10. Blue Laser Recording A. High Definition Video B. Blu-ray versus HD DVD C. Laser wavelengths a. Numerical aperture b. Comparison of High Definition Proposals 11. Life-time Expectations of Optical Media 12. Care and Handling of Optical Media 2 FAQs about Optical Media There is a great deal of misinformation, hype, and misunderstanding in the field of optical media. -

![MZ-R501\3234036131MZR501UCE\01COV- MZR501UCE\00GB01COV-CED.Fm] Masterpage:Right](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7319/mz-r501-3234036131mzr501uce-01cov-mzr501uce-00gb01cov-ced-fm-masterpage-right-977319.webp)

MZ-R501\3234036131MZR501UCE\01COV- MZR501UCE\00GB01COV-CED.Fm] Masterpage:Right

filename[\\Ww001\WW001\ON GOING\MZ-R501\3234036131MZR501UCE\01COV- MZR501UCE\00GB01COV-CED.fm] masterpage:Right 00GB01COV-CED.fm Page 1 Monday, November 5, 2001 1:37 PM 3-234-036-13(1) Portable MiniDisc Recorder Operating Instructions WALKMAN and are trademarks of Sony Corporation. MZ-R501/R501PC/R501DPC © 2001 Sony Corporation model name1[MZ-R501/R501PC/R501DPC] model name2[MZ-----] [3-234-036-13(1)] Certain countries may regulate disposal of WARNING battery used to power this product. To prevent fire or shock hazard, do Please consult with your local authority. not expose the unit to rain or moisture. For customers in the USA To avoid electrical shock, do not Owner’s Record open the cabinet. Refer servicing to The serial number is located at the rear of qualified personnel only. the disc compartment lid and the model number is located at the top and bottom. Do not install the appliance in a Record the serial number in the space confined space, such as a bookcase or provided below. Refer to them whenever you call upon your Sony dealer regarding built-in cabinet. this product. Model No. To prevent fire, do not cover the Serial No. ventilation of the apparatus with news papers, table cloths, curtains, etc. And This equipment has been tested and found don’t place lighted candles on the to comply with the limits for a Class B apparatus. digital device, pursuant to Part 15 of the FCC Rules. These limits are designed to To prevent fire or shock hazard, do not provide reasonable protection against place objects filled with liquids, such as harmful interference in a residential vases, on the apparatus.