It's a Bird! It's a Plane!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE DECAY of LYING Furniture of “The Street Which from Oxford Has Borrowed Its by OSCAR WILDE Name,” As the Poet You Love So Much Once Vilely Phrased It

seat than the whole of Nature can. Nature pales before the THE DECAY OF LYING furniture of “the street which from Oxford has borrowed its BY OSCAR WILDE name,” as the poet you love so much once vilely phrased it. I don’t complain. If Nature had been comfortable, mankind would A DIALOGUE. never have invented architecture, and I prefer houses to the open Persons: Cyril and Vivian. air. In a house we all feel of the proper proportions. Everything is Scene: the library of a country house in Nottinghamshire. subordinated to us, fashioned for our use and our pleasure. Egotism itself, which is so necessary to a proper sense of human CYRIL (coming in through the open window from the terrace). dignity, is entirely the result of indoor life. Out of doors one My dear Vivian, don’t coop yourself up all day in the library. It becomes abstract and impersonal. One’s individuality absolutely is a perfectly lovely afternoon. The air is exquisite. There is a leaves one. And then Nature is so indifferent, so unappreciative. mist upon the woods like the purple bloom upon a plum. Let us Whenever I am walking in the park here, I always feel that I am go and lie on the grass, and smoke cigarettes, and enjoy Nature. no more to her than the cattle that browse on the slope, or the VIVIAN. Enjoy Nature! I am glad to say that I have entirely lost burdock that blooms in the ditch. Nothing is more evident than that faculty. People tell us that Art makes us love Nature more that Nature hates Mind. -

Sloane Drayson Knigge Comic Inventory (Without

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Number Donor Box # 1,000,000 DC One Million 80-Page Giant DC NA NA 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 A Moment of Silence Marvel Bill Jemas Mark Bagley 2002 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alex Ross Millennium Edition Wizard Various Various 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Open Space Marvel Comics Lawrence Watt-Evans Alex Ross 1999 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alf Marvel Comics Michael Gallagher Dave Manak 1990 33 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 2 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 3 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 4 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 5 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 6 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Aphrodite IX Top Cow Productions David Wohl and Dave Finch Dave Finch 2000 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 600 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 601 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 602 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 603 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 -

Club Add 2 Page Designoct07.Pub

H M. ADVS. HULK V. 1 collects #1-4, $7 H M. ADVS FF V. 7 SILVER SURFER collects #25-28, $7 H IRR. ANT-MAN V. 2 DIGEST collects #7-12,, $10 H POWERS DEF. HC V. 2 H ULT FF V. 9 SILVER SURFER collects #12-24, $30 collects #42-46, $14 H C RIMINAL V. 2 LAWLESS H ULTIMATE VISON TP collects #6-10, $15 collects #0-5, $15 H SPIDEY FAMILY UNTOLD TALES H UNCLE X-MEN EXTREMISTS collects Spidey Family $5 collects #487-491, $14 Cut (Original Graphic Novel) H AVENGERS BIZARRE ADVS H X-MEN MARAUDERS TP The latest addition to the Dark Horse horror line is this chilling OGN from writer and collects Marvel Advs. Avengers, $5 collects #200-204, $15 Mike Richardson (The Secret). 20-something Meagan Walters regains consciousness H H NEW X-MEN v5 and finds herself locked in an empty room of an old house. She's bleeding from the IRON MAN HULK back of her head, and has no memory of where the wound came from-she'd been at a collects Marvel Advs.. Hulk & Tony , $5 collects #37-43, $18 club with some friends . left angrily . was she abducted? H SPIDEY BLACK COSTUME H NEW EXCALIBUR V. 3 ETERNITY collects Back in Black $5 collects #16-24, $25 (on-going) H The End League H X-MEN 1ST CLASS TOMORROW NOVA V. 1 ANNIHILATION A thematic merging of The Lord of the Rings and Watchmen, The End League follows collects #1-8, $5 collects #1-7, $18 a cast of the last remaining supermen and women as they embark on a desperate and H SPIDEY POWER PACK H HEROES FOR HIRE V. -

Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Literary Anglo-Saxon

ENVIRONMENTAL HUMANITIES IN PRE-MODERN CULTURES Estes Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Heide Estes Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Ecotheory and the Environmental Imagination Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Environmental Humanities in Pre‑modern Cultures This series in environmental humanities offers approaches to medieval, early modern, and global pre-industrial cultures from interdisciplinary environmental perspectives. We invite submissions (both monographs and edited collections) in the fields of ecocriticism, specifically ecofeminism and new ecocritical analyses of under-represented literatures; queer ecologies; posthumanism; waste studies; environmental history; environmental archaeology; animal studies and zooarchaeology; landscape studies; ‘blue humanities’, and studies of environmental/natural disasters and change and their effects on pre-modern cultures. Series Editor Heide Estes, University of Cambridge and Monmouth University Editorial Board Steven Mentz, St. John’s University Gillian Overing, Wake Forest University Philip Slavin, University of Kent Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Ecotheory and the Environmental Imagination Heide Estes Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: © Douglas Morse Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Layout: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 944 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 838 7 doi 10.5117/9789089649447 nur 617 | 684 | 940 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The author / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

Media Industry Approaches to Comic-To-Live-Action Adaptations and Race

From Serials to Blockbusters: Media Industry Approaches to Comic-to-Live-Action Adaptations and Race by Kathryn M. Frank A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Lisa A. Nakamura Associate Professor Aswin Punathambekar © Kathryn M. Frank 2015 “I don't remember when exactly I read my first comic book, but I do remember exactly how liberated and subversive I felt as a result.” ― Edward W. Said, Palestine For Mom and Dad, who taught me to be my own hero ii Acknowledgements There are so many people without whom this project would never have been possible. First and foremost, my parents, Paul and MaryAnn Frank, who never blinked when I told them I wanted to move half way across the country to read comic books for a living. Their unending support has taken many forms, from late-night pep talks and airport pick-ups to rides to Comic-Con at 3 am and listening to a comics nerd blather on for hours about why Man of Steel was so terrible. I could never hope to repay the patience, love, and trust they have given me throughout the years, but hopefully fewer midnight conversations about my dissertation will be a good start. Amanda Lotz has shown unwavering interest and support for me and for my work since before we were formally advisor and advisee, and her insight, feedback, and attention to detail kept me invested in my own work, even in times when my resolve to continue writing was flagging. -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

Exhibit B: Business and Business Plan VIRAL FILMS MEDIA LLC

Exhibit B: Business and Business Plan VIRAL FILMS MEDIA LLC BUSINESS AND BUSINESS PLAN Viral Films Media LLC Producing an independent live-action superhero film: REBEL'S RUN Business Plan Summary Our recently formed company, Viral Films Media LLC, will produce, market and distribute an independently produced live-action superhero film, based on characters from the recently created Alt Hero comic book universe. The film will be titled Rebel’s Run, and will feature the character Shiloh Summers, or Rebel, from the Alt Hero comic book series. Viral Films has arranged to license a script and related IP from independent comic book publisher Arkhaven Comics, with comic book legend Chuck Dixon and epic fantasy author Vox Day co-writing the script. Viral Films Media is also partnering with Georgia and LA-based production company, Galatia Films, which has worked on hits including Goodbye, Christopher Robin and Reclaiming the Blade. The director of Rebel’s Run will be Scooter Downey, an up-and-coming director who recently co-produced Hoaxed, the explosive and acclaimed documentary on the fake news phenomenon. The filming of Rebel’s Run will take place in Georgia. We have formed a board of directors and management team including a range of professionals with experience in project management, law, film production and cyber-security. (image from Alt Hero, # 2, which introduced the character Shiloh Summers, or Rebel.) Film Company Overview Viral Films Media LLC (VFM) is a new film studio with the business purpose of creating a live-action superhero film – Rebel’s Run – based on characters from the ALT-HERO comic book universe created by Chuck Dixon, Vox Day and Arkhaven Comics. -

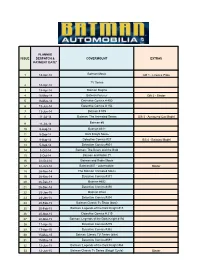

Issue Planned Despatch & Payment Date* Covermount

PLANNED ISSUE DESPATCH & COVERMOUNT EXTRAS PAYMENT DATE* 1 18-Apr-14 Batman Movie Gift 1 - Licence Plate TV Series 2 18-Apr-14 3 18-Apr-14 Batman Begins 4 16-May-14 Batman Forever Gift 2 - Binder 5 16-May-14 Detective Comics # 400 6 13-Jun-14 Detective Comics # 156 7 13-Jun-14 Batman # 575 8 11-Jul-14 Batman: The Animated Series Gift 3 - Armoured Car Model 9 11-Jul-14 Batman #5 10 8-Aug-14 Batman #311 11 5-Sep-14 Dark Knight Movie 12 8-Aug-14 Detective Comics #27 Gift 4 - Batwing Model 13 5-Sep-14 Detective Comics #601 14 3-Oct-14 Batman: The Brave and the Bold 15 3-Oct-14 Batman and Robin #1 16 31-Oct-14 Batman and Robin Movie 17 31-Oct-14 Batman #37 - Jokermobile Binder 18 28-Nov-14 The Batman Animated Movie 19 28-Nov-14 Detective Comics #371 20 26-Dec-14 Batman #652 21 26-Dec-14 Detective Comics #456 22 23-Jan-15 Batman #164 23 23-Jan-15 Detective Comics #394 24 20-Feb-15 Batman Classic Tv Show (boat) 25 20-Feb-15 Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight #15 26 20-Mar-15 Detective Comics # 219 27 20-Mar-15 Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight #156 28 17-Apr-15 Detective Comics #219 29 17-Apr-15 Detective Comics #362 30 15-May-15 Batman Classic TV Series (bike) 31 15-May-15 Detective Comics #591 32 12-Jun-15 Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight #64 33 12-Jun-15 Batman Classic Tv Series (Batgirl Cycle) Binder 34 10-Jul-15 Batman Arkham Asylum Video Game 35 10-Jul-15 Batman & Robin (Vol 2) #5 36 7-Aug-15 Detective Comics #667 (Subway Rocket) 37 7-Aug-15 Batman Beyond: Animated Series 38 4-Sep-15 Legends of the Dark Knight (Bike) 39 27-Nov-15 All Star Batman & Robin The Boy Wonder #1 40 4-Sep-15 The Dark Knight Rises Movie 41 2-Oct-15 Batman The Return #1 42 2-Oct-15 The New Adventures of Batman. -

(Mr) 3,60 € Aug18 0015 Citize

Συνδρομές και Προπαραγγελίες Comics Αύγουστος 2018 (για Οκτώβριο- Nοέμβριο 2018) Μέχρι τις 17 Αυγούστο, στείλτε μας email στο [email protected] με θέμα "Προπαραγγελίες Comics Αύγουστος 2018": Ονοματεπώνυμο Username Διεύθυνση, Πόλη, ΤΚ Κινήτο τηλέφωνο Ποσότητα - Κωδικό - Όνομα Προϊόντος IMAGE COMICS AUG18 0013 BLACKBIRD #1 CVR A BARTEL 3,60 € AUG18 0014 BLACKBIRD #1 CVR B STAPLES (MR) 3,60 € AUG18 0015 CITIZEN JACK TP (APR160796) (MR) 13,49 € AUG18 0016 MOTOR CRUSH TP VOL 01 (MAR170820) 8,49 € AUG18 0017 MOTOR CRUSH TP VOL 02 (MAR180718) 15,49 € AUG18 0018 DEAD RABBIT #1 CVR A MCCREA (MR) 3,60 € AUG18 0020 INFINITE HORIZON TP (FEB120448) 16,49 € AUG18 0021 LAST CHRISTMAS HC (SEP130533) 22,49 € AUG18 0022 MYTHIC TP VOL 01 (MAR160637) (MR) 15,49 € AUG18 0023 ERRAND BOYS #1 (OF 5) CVR A KOUTSIS 3,60 € AUG18 0024 ERRAND BOYS #1 (OF 5) CVR B LARSEN 3,60 € AUG18 0025 POPGUN GN VOL 01 (NEW PTG) (SEP071958) 26,99 € AUG18 0026 POPGUN GN VOL 02 (MAY082176) 26,99 € AUG18 0027 POPGUN GN VOL 03 (JAN092368) 26,99 € AUG18 0028 POPGUN GN VOL 04 (DEC090379) 26,99 € AUG18 0029 EXORSISTERS #1 CVR A LAGACE 3,60 € AUG18 0030 EXORSISTERS #1 CVR B GUERRA 3,60 € AUG18 0033 DANGER CLUB TP VOL 01 (SEP120436) 8,49 € AUG18 0034 DANGER CLUB TP VOL 02 REBIRTH (APR150581) 8,49 € AUG18 0035 PLUTONA TP (MAR160642) 15,49 € AUG18 0036 INFINITE DARK #1 3,60 € AUG18 0037 HADRIANS WALL TP (JUN170665) (MR) 17,99 € AUG18 0038 WARFRAME TP VOL 01 (O/A) 17,99 € AUG18 0039 JOOK JOINT #1 (OF 5) CVR A MARTINEZ (MR) 3,60 € AUG18 0040 JOOK JOINT #1 (OF 5) CVR B HAWTHORNE (MR) 3,60 -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

Press™ Kit 01 Contents

NO SAFE HARBOUR ™ SEASON TWO ® ® PRESS™ KIT 01 CONTENTS 03 SYNOPSIS 04 CAST & CHARACTERS 23 PRODUCTION BIOGRAPHIES 28 INTERVIEW: DAVE ERICKSON EXECUTIVE PRODUCER & SHOWRUNNER 31 PRODUCTION CREDITS ® ™ SYNOPSIS Last season, Fear the Walking Dead explored a blended family who watched a burning, dead city as they traversed a devastated Los Angeles. In season two, the group aboard the ‘Abigail’ is unaware of the true breadth and depth of the apocalypse that surrounds them; they assume there is still a chance that some city, state, or nation might be unaffected - some place that the Infection has not reached. But as Operation Cobalt goes into full effect, the military bombs the Southland to cleanse it of the Infected, driving the Dead toward the sea. As Madison, Travis, Daniel, and their grieving families head for ports unknown, they will discover that the water may be no safer than land. ® ™ 03 CAST & CHARACTERS ® ™ 04 MADISON CLARK In many ways, the Madison of season two is the same woman we met in the pilot - a leader, a moral compass - but in a whole new devastated, apocalyptic world. As the season plays out, Madison will be faced with a world that often has no room for empathy or compassion. Forced to navigate a deceptive and manipulative chart of personalities, Madison’s success in this new world is predicated on understanding that, at the end of the world, lending a helping hand can often endanger those you love. She may maintain her maternal ferocity, but the apocalypse will force her to make decisions and sacrifices that could break even the strongest people.