United States District Court District of Connecticut

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long Island Alewife Monitoring Training Sessions

If you are having trouble viewing this email, View a web page version. January 29, 2016 DO YOUR PART VOLUNTEER FOR THE SOUND! There are many organizations in Connecticut and New York that need your help restoring and protecting Long Island Sound! Long Island Alewife Monitoring Training Sessions Learn about the river herring’s migration and take part in monitoring its spawning activity. All are welcome to attend and participate in this citizen science project. No experience required. Credit: NOAA Monday, February 29, 2016 at 4:305:30pm at the Cold Spring Harbor Whaling Museum, 301 Main Street, Cold Spring Harbor, NY 11724. Contact Cassie Bauer and Amy Mandelbaum at [email protected] or 6314440474 to RSVP and for more information. Click here for the flyer. Thursday, March 3, 2016 at 5:306:30pm at the Town of North Hempstead Town Hall, 220 North Plandome Road, Manhasset, NY 11030. Contact Cassie Bauer and Amy Mandelbaum at [email protected] or 6314440474 to RSVP and for more information. Click here for the flyer. Citizen Science Around the Sound Are you concerned about beach closures at your local beach? How about horseshoe crabs spawning along Long Island Sound? If you’re interested in solving an environmental problem in your community or studying the world around you, then citizen science is for you. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “citizen science is a vital, fastgrowing field in which scientific investigations are conducted by volunteers.” Rocking the Boat Environmental Job Skills Apprentices on the Bronx River. -

Norwalk Harbor Report Card Is Part of a Larger Effort to Assess Long Island Sound Health on an Annual Basis

Norwalk Harbor C+ Report Card Following the water’s trail from your house, into the river, and to the Harbor The way land is used in a watershed has a Harmful practices Beneficial practices significant effect on water quality. In areas where there are more impervious surfaces, such as parking lots, streets, and roofs, water from storms and even light rain can flow quickly and directly into a storm drain system. This water flow, called runoff, transports a wide variety of pollutants (such as sediments, excess nutrients, bacteria, and toxic man-made chemicals) into nearby streams, rivers, and the Harbor. This type of pollution, often difficult to control, is called Nonpoint Source Pollution (NSP). NSP can cause the destruction of fish and macroinvertebrate habitats, promote the growth of excessive and unwanted algal blooms that Infrastructure Pollution Sources Inputs contribute to hypoxia (low dissolved oxygen) Storm water pipe Oil Bacteria events in Long Island Sound, and introduce Sewer pipe Pet waste Nutrients dangerous chemicals into local waterways. These pollutants that run off the land threaten Storm drain Illegal hookup Toxicants the biological integrity of the Sound and the Rain garden Broken and leaking sewers recreational and commercial value of this important resource. In addition to the harmful Nonpoint source pollution can enter Norwalk Harbor from pet waste, illegal hookups, broken pipes, and car oil spills. When proper sewer and car effects on the overall Sound, negative impacts maintenance practices and rain gardens are used, pollution is prevented. can be seen locally in Norwalk River and Harbor. Your actions can help improve the Harbor! Compost yard waste, Be a considerate pet owner. -

Harbor Health Study: 2019

Harbor Health Study Harbor Watch | 2019 Harbor Health Study: 2019 Sarah C. Crosby1 Richard B. Harris2 Peter J. Fraboni1 Devan E. Shulby1 Nicole C. Spiller1 Kasey E. Tietz1 1Harbor Watch, Earthplace Inc., Westport, CT 06880 2Copps Island Oysters, Norwalk, CT 06851 This report includes data on: Demersal fish study in Norwalk Harbor and dissolved oxygen studies in Stamford Harbor, Five Mile Harbor, Norwalk Harbor, Saugatuck Harbor, Bridgeport Harbor (Johnson’s Creek and Lewis Gut sections), and New Haven Harbor (Quinnipiac River section) Harbor Health Study 2019, Harbor Watch | 1 Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Sue Steadham and the Wilton High School Marine Biology Club, Katie Antista, Melissa Arenas, Rachel Bahouth, JP Barce, Maria and Ridgway Barker, Dave Cella, Helen Cherichetti, Christopher Cirelli, Ashleigh Coltman, Matthew Carrozza, Dalton DiCamillo, Vivian Ding, Julia Edwards, Alec Esmond, Joe Forleo, Natalia Fortuna, Lily Gardella, Sophie Gaspel, Cem Geray, Camille Goodman, William Hamson, Miranda Hancock, Eddie Kiev, Samantha Kortekaas, Alexander Koutsoukos, Lucas Koutsoukos, Corey Matais, Sienna Matregrano, Liam McAuliffe, Kelsey McClung, Trisha Mhatre, Maya Mhatre, Clayton Nyiri, “Pogy” Pogany, Rachel Precious, Joe Racz, Sandy Remson, Maddie SanAngelo, Janak Sekaran, Max Sod, Joshua Springer, Jacob Trock, JP Valotti, Margaret Wise, Liv Woodruff, Bill Wright, and Aby Yoon, Gino Bottino, Bernard Camarro, Joe DeFranco, Sue Fiebich, Jerry Frank, John Harris, Rick Keen, Joe Lovas, Dave Pierce, Eric Riznyk, Carol Saar, Emmanuel Salami, Robert Talley, Ezra Williams . We would also like to extend our gratitude to Norm Bloom and Copps Island Oysters for their tremendous support, donation of a dock slip and instrumental boating knowledge to keep our vessel afloat. -

Waterbody Regulations and Boat Launches

to boating in Connecticut! TheWelcome map with local ordinances, state boat launches, pumpout facilities, and Boating Infrastructure Grant funded transient facilities is back again. New this year is an alphabetical list of state boat launches located on Connecticut lakes, ponds, and rivers listed by the waterbody name. If you’re exploring a familiar waterbody or starting a new adventure, be sure to have the proper safety equipment by checking the list on page 32 or requesting a Vessel Safety Check by boating staff (see page 14 for additional information). Reference Reference Reference Name Town Number Name Town Number Name Town Number Amos Lake Preston P12 Dog Pond Goshen G2 Lake Zoar Southbury S9 Anderson Pond North Stonington N23 Dooley Pond Middletown M11 Lantern Hill Ledyard L2 Avery Pond Preston P13 Eagleville Lake Coventry C23 Leonard Pond Kent K3 Babcock Pond Colchester C13 East River Guilford G26 Lieutenant River Old Lyme O3 Baldwin Bridge Old Saybrook O6 Four Mile River Old Lyme O1 Lighthouse Point New Haven N7 Ball Pond New Fairfield N4 Gardner Lake Salem S1 Little Pond Thompson T1 Bantam Lake Morris M19 Glasgo Pond Griswold G11 Long Pond North Stonington N27 Barn Island Stonington S17 Gorton Pond East Lyme E9 Mamanasco Lake Ridgefield R2 Bashan Lake East Haddam E1 Grand Street East Lyme E13 Mansfield Hollow Lake Mansfield M3 Batterson Park Pond New Britain N2 Great Island Old Lyme O2 Mashapaug Lake Union U3 Bayberry Lane Groton G14 Green Falls Reservoir Voluntown V5 Messerschmidt Pond Westbrook W10 Beach Pond Voluntown V3 Guilford -

2021 Connecticut Boater's Guide Rules and Resources

2021 Connecticut Boater's Guide Rules and Resources In The Spotlight Updated Launch & Pumpout Directories CONNECTICUT DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY & ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION HTTPS://PORTAL.CT.GOV/DEEP/BOATING/BOATING-AND-PADDLING YOUR FULL SERVICE YACHTING DESTINATION No Bridges, Direct Access New State of the Art Concrete Floating Fuel Dock Offering Diesel/Gas to Long Island Sound Docks for Vessels up to 250’ www.bridgeportharbormarina.com | 203-330-8787 BRIDGEPORT BOATWORKS 200 Ton Full Service Boatyard: Travel Lift Repair, Refit, Refurbish www.bridgeportboatworks.com | 860-536-9651 BOCA OYSTER BAR Stunning Water Views Professional Lunch & New England Fare 2 Courses - $14 www.bocaoysterbar.com | 203-612-4848 NOW OPEN 10 E Main Street - 1st Floor • Bridgeport CT 06608 [email protected] • 203-330-8787 • VHF CH 09 2 2021 Connecticut BOATERS GUIDE We Take Nervous Out of Breakdowns $159* for Unlimited Towing...JOIN TODAY! With an Unlimited Towing Membership, breakdowns, running out GET THE APP IT’S THE of fuel and soft ungroundings don’t have to be so stressful. For a FASTEST WAY TO GET A TOW year of worry-free boating, make TowBoatU.S. your backup plan. BoatUS.com/Towing or800-395-2628 *One year Saltwater Membership pricing. Details of services provided can be found online at BoatUS.com/Agree. TowBoatU.S. is not a rescue service. In an emergency situation, you must contact the Coast Guard or a government agency immediately. 2021 Connecticut BOATER’S GUIDE 2021 Connecticut A digest of boating laws and regulations Boater's Guide Department of Energy & Environmental Protection Rules and Resources State of Connecticut Boating Division Ned Lamont, Governor Peter B. -

Rwalk River ~ Watershed

$66! RWALK RIVER ~ WATERSHED I’-tmd.s to ,~upport prittting ~/ thi.s d~*cument were provided mtth’r A.~si.stance Agreement # X991480 tn,tweett the U.S. Enviromnental Protectiott .4k,~,ttcv, New Englatul. ttnd the, N~’u’ Ettgltmd htterstate Writer Polhttion 17~is document is printed on recycled paper "We envision a restored Norwalk River Watershed system: one that is healthy, dynamic and will remain so for generations to come; one that offers clean water and functioning wetlands; one in which a diversiO, of freshwater and anadromous fish as well as other wild- life and plants are once again sustained; one in which the river sys- tem is an attractive communiO, resource that enhances quali~, of life, education, tourism and recreation; and above all, one in which growth re&ects this vision and all people participate in the stew- ardship of the watershed." Norwalk River Watershed Initiative Committee, 1998 Bruce Ando Barbara Findley Oswald lnglese Dau Porter Chester Arnold Angela Forese Vijay Kambli K. Kaylan Raman John Atkin Nuthan Frohling Jessica Kaplan Phil Renn Marcy Balint Briggs Geddis Bill Kerin James Roberts Todd Bobowick Nelson Gelfman Rod Klukas Lori Romick Lisa Carey Sheldon Gerarden Diane Lauricella Dianne Selditch Richard Carpenter Michael Greene John Black Lee Patricia Sesto Sabrina Charney Tessa Gutowski Melissa Leigh Marny Smith Christie Coon Roy Haberstock Jonathan Lewengrub Walter Smith Mel Cote Victor Hantbrd Jim Lucey Gary Sorge Steve Danzer Kenneth Hapke, Esq. Paul Maniccia Brian Thompson Victor DeMasi Dick Harris Elizabeth Marks Ed Vallerie Carol Donzella Thomas Havlick Phil Morneault Vincent Ventrano Deborah Ducoff-Barone Mark Hess John Morrisson Helene Verglas Dave Dunavan Laura Heyduk Raymond Morse Ernie Wiegand Jerome Edwards William Hubard Steve Nakashima Bill Williams Harry Everson Carolyn Hughes Dave Pattee Lillian Willis J. -

Harbor Watch | 2016

Harbor Watch | 2016 Fairfield County River Report: 2016 Sarah C. Crosby Nicole L. Cantatore Joshua R. Cooper Peter J. Fraboni Harbor Watch, Earthplace Inc., Westport, CT 06880 This report includes data on: Byram River, Farm Creek, Mianus River, Mill River, Noroton River, Norwalk River, Poplar Plains Brook, Rooster River, Sasco Brook, and Saugatuck River Acknowledgements The authors with to thank Jessica Ganim, Fiona Lunt, Alexandra Morrison, Ken Philipson, Keith Roche, Natalie Smith, and Corrine Vietorisz for their assistance with data collection and laboratory analysis. Funding for this research was generously provided by Jeniam Foundation, Social Venture Partners of Connecticut, Copps Island Oysters, Atlantic Clam Farms, 11th Hour Racing Foundation, City of Norwalk, Coastwise Boatworks, Environmental Professionals’ Organization of Connecticut, Fairfield County’s Community Foundation, General Reinsurance, Hillard Bloom Shellfish, Horizon Foundation, Insight Tutors, King Industries, Long Island Sound Futures Fund, McCance Family Foundation, New Canaan Community Foundation, Newman’s Own Foundation, Norwalk Cove Marina, Norwalk River Watershed Association, NRG – Devon, Palmer’s Market, Pramer Fuel, Resnick Advisors, Rex Marine Center, Soundsurfer Foundation, Town of Fairfield, Town of Ridgefield, Town of Westport, Town of Wilton, Trout Unlimited – Mianus Chapter. Additional support was provided by the generosity of individual donors. This report should be cited as: S.C. Crosby, N.L. Cantatore, J.R. Cooper, and P.J. Fraboni. 2016. Fairfield -

East Norwalk Historical Walks

EAST NORWALK HISTORICAL WALKS Whenever you are in East Norwalk or the Calf Pasture Beach area you are surrounded by locations important in Norwalk history. For thousands of years the native American Indians lived here. They built their dwellings along the shoreline. Since their dwellings were surrounded by a stockade for defense against warlike tribes, early Europeans called the Indians' living area a Fort. They lived on the bounties of the sea, the local environment which teamed with wildlife and also planted corn. In 1614, Adriaen Block, a navigator from the Netherlands, whose ship the Restless was sailing along the Connecticut Coast trading with the Indians, recorded his visit to what he called "The Archipelago". His written record was the first mention of what we know as the Norwalk Islands. The Pequot Wars (1637-1638) brought Colonial Soldiers close to this area and the final battle of the war was fought in what is called the Sasqua swamp, an area now part of Fairfield, CT at the Southport line. Two of the leaders of these soldiers, Roger Ludlow and Daniel Partrick were impressed by the potential of the area and independently purchased land from the Indians in 1640/1641. Ludlow bought the land between the Saugatuck River and the middle of the Norwalk River (approximately 15,777 acres) and Partrick bought the land from the middle of the Norwalk River east to the Five-Mile River. Neither one, so far as we know, ever lived on the land that they purchased. A monument to Roger Ludlow is within the traffic circle at the junction of Calf Pasture Beach Road and Gregory Boulevard. -

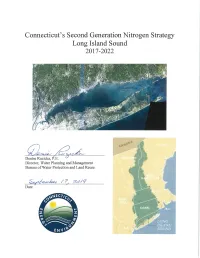

Connecticut's Second Generation Nitrogen Strategy

Table of Contents Purpose ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Background ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Second Generation Nitrogen Strategy ............................................................................................ 4 Wastewater Treatment Plants ..................................................................................................... 4 Nonpoint Sources and Stormwater ............................................................................................. 4 Embayments ................................................................................................................................ 5 Status of Nitrogen Loading to Long Island Sound ......................................................................... 8 Hypoxia Trends in Offshore Long Island Sound .......................................................................... 10 Nitrogen Loading and Embayments ............................................................................................. 12 EPA’s Nitrogen Reduction Strategy ............................................................................................. 15 Relevant Reports and Publications ............................................................................................... 16 On the Cover: Long Island Sound Aerial Photo Source – UCONN https://lis.research.cuconn.edu/ -

Norwalk Harbor: the Jewel of Long Island Sound

Norwalk Harbor: The Jewel of Long Island Sound A Presentation by the Norwalk Harbor Management Commission 2019 State of the Harbor Meeting December 11, 2019 1 The City of Norwalk in Southwest Connecticut Connecticut Norwalk is a coastal community on the north shore of Long Island Sound, part of the coastal area of the State of Connecticut as defined in the Norwalk Connecticut Coastal ● Management Act. Norwalk’s character and quality of life are intrinsically tied to the water and shoreline resources of Long Island Sound and Norwalk Harbor. 2 Norwalk Harbor Located at the mouth of the Norwalk River, Norwalk Harbor extends inland from south of the Norwalk Islands to the head of navigation at Wall Street. Harbor boundaries are established in the City Charter; harbor waters are divided into an Inner and Outer Harbor. A Federal Navigation Project authorized by the U.S. Congress and consisting of designated navigation channels and anchorage basins has served the harbor since the late 19th century. Included are a dredged channel 12 feet deep from the mouth of the river to the Stroffolino Bridge; a ten-foot channel upstream to Wall Street; and a six-foot channel to East Norwalk. 3 Historic Maritime Community Much of Norwalk’s history, from the area’s first settlement in 1640, can be told with respect to the City’s location on Long Island Sound and Norwalk Harbor. The first commercial docks were built upstream on the Norwalk River at the “head of navigation” in the 1700s. By the end of the 18th century, wharves and warehouses were found all along the waterfront. -

NWRS Tear Sheet 2020

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge, Chimon and Sheffield Island Hunting Regulations Welcome Hunt Information Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Waterfowl and white-tailed deer hunting occurs on all areas of the Chimon and Sheffield Refuge consists of ten units located along Island Units, unless denoted by “No Hunting Zone” signage. Hunters should be aware the coast of Connecticut from Westbrook that a portion of Sheffield Island is privately owned and not part of the refuge (see map on to Greenwich. Due to its location within reverse). All Connecticut hunting regulations apply, including season dates and harvest limits. the Atlantic Flyway, the refuge provides Waterfowl may be hunted with all permitted methods of take, per State regulations. White- important resting, feeding, and nesting tailed deer hunting on these units is archery only. habitat for many species of birds Firearms including the endangered roseate tern Persons possessing, transporting, or carrying firearms on National Wildlife Refuge System and threatened piping plover. Part of the lands must comply with all provisions of State and local law. Persons may only use Norwalk Islands archipelago, the Sheffield (discharge) firearms in accordance with refuge regulations (50 CFR 27.42 and specific refuge (51 acres as part of the refuge) and regulations in 50 CFR Part 32.) Chimon Island (68 acres) Units are located Safety south of the bustling Norwalk Harbor Hunters operating motorboats to reach refuge islands, or through refuge marsh areas, should Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge always be aware of marine weather conditions and tide changes. Entering certain areas of 733 Old Clinton Road, Westbrook, CT 06498 860-399-2513 the refuge is likely to expose hunters to mosquitoes, ticks, and other disease-carrying insects. -

Connecticut Sea Grant Project Report

1 CONNECTICUT SEA GRANT PROJECT REPORT Please complete this progress or final report form and return by the date indicated in the emailed progress report request from the Connecticut Sea Grant College Program. Fill in the requested information using your word processor (i.e., Microsoft Word), and e-mail the completed form to Dr. Syma Ebbin [email protected], Research Coordinator, Connecticut Sea Grant College Program. Do NOT mail or fax hard copies. Please try to address the specific sections below. If applicable, you can attach files of electronic publications when you return the form. If you have questions, please call Syma Ebbin at (860) 405-9278. Please fill out all of the following that apply to your specific research or development project. Pay particular attention to goals, accomplishments, benefits, impacts and publications, where applicable. Project #: __R/CE-34-CTNY__ Check one: [ ] Progress Report [ x ] Final report Duration (dates) of entire project, including extensions: From [March 1, 2013] to [August 28, 2015 ]. Project Title or Topic: Comparative analysis and model development for determining the susceptibility to eutrophication of Long Island Sound embayment. Principal Investigator(s) and Affiliation(s): 1. Jamie Vaudrey, Department of Marine Sciences, University of Connecticut 2. Charles Yarish, Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Department of Marine Sciences, University of Connecticut 3. Jang Kyun Kim, Department of Marine Sciences, University of Connecticut 4. Christopher Pickerell, Marine Program, Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County 5. Lorne Brousseau, Marine Program, Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County A. COLLABORATORS AND PARTNERS: (List any additional organizations or partners involved in the project.) Justin Eddings, Marine Program, Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County Michael Sautkulis, Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County Veronica Ortiz, University of Connecticut Jeniam Foundation (Tripp Killin, Exec.