Screening Race: Constructions and Reconstructions in Twenty-First Century Media – Editorial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sideways Title Page

SIDEWAYS by Alexander Payne & Jim Taylor (Based on the novel by Rex Pickett) May 29, 2003 UNDER THE STUDIO LOGO: KNOCKING at a door and distant dog BARKING. NOW UNDER BLACK, A CARD -- SATURDAY The rapping, at first tentative and polite, grows insistent. Then we hear someone getting out of bed. MILES (O.S.) ...the fuck... A door is opened, and the black gives way to blinding white light, the way one experiences the first glimpse of day amid, say, a hangover. A worker, RAUL, is there. MILES (O.S.) Yeah? RAUL Hi, Miles. Can you move your car, please? MILES (O.S.) What for? RAUL The painters got to put the truck in, and you didn’t park too good. MILES (O.S.) (a sigh, then --) Yeah, hold on. He closes the door with a SLAM. EXT. HIDEOUS APARTMENT COMPLEX - DAY SUPERIMPOSE -- SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA Wearing only underwear, a bathrobe, and clogs, MILES RAYMOND comes out of his unit and heads toward the street. He passes some SIX MEXICANS, ready to work. 2. He climbs into his twelve-year-old convertible SAAB, parked far from the curb and blocking part of the driveway. The car starts fitfully. As he pulls away, the guys begin backing up the truck. EXT. STREET - DAY Miles rounds the corner and finds a new parking spot. INT. CAR - CONTINUOUS He cuts the engine, exhales a long breath and brings his hands to his head in a gesture of headache pain or just plain anguish. He leans back in his seat, closes his eyes, and soon nods off. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

An Lkd Films Production Presents

AN LKD FILMS PRODUCTION PRESENTS: RUNNING TIME.......................... 96 MIN GENRE ........................................ CRIME/DRAMA RATING .......................................NOT YET RATED YEAR............................................ 2015 LANGUAGE................................. ENGLISH COUNTRY OF ORIGIN ................ UNITED STATES FORMAT ..................................... 1920x1080, 23.97fps, 16:9, SounD 5.1 LINKS .......................................... Website: www.delinquentthemovie.com Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Delinquentthefilm/ IMDB: http://www.imDb.com/title/tt4225478/ Instagram: @delinquentmovie Hashtag: #delinquentmovie, #delinquentfilm SYNOPSIS The principal is itching to kick Joey out of high school, anD Joey can’t wait to get out. All he wants is to work for his father, a tree cutter by day anD the leader of a gang of small-time thieves by night in rural Connecticut. So when Joey’s father asks him to fill in as a lookout, Joey is thrilleD until a routine robbery goes very wrong. Caught between loyalties to family anD a chilDhood frienD in mourning. Joey has to deal with paranoiD accomplices, a criminal investigation, anD his own guilt. What kinD of man does Joey want to be, anD what does he owe to the people he loves? DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT My home state of Connecticut is depicteD in Television anD Film as the lanD of the wealthy anD privileged: country clubs, yachts, anD salmon coloreD polo shirts galore. Although many of these elements do exist, there is another siDe of Connecticut that is not often seen. It features blue-collar workers, troubleD youth, anD families living on the fringes. I was raiseD in WooDbury, a small town in LitchfielD Country that restricteD commercial businesses from operating within its borders. WooDbury haD a large disparity in its resiDent’s householD income anD over one hundreD antique shops that lineD the town’s “Main St.” I grew up in the rural part of town where my house shareD a property with my father’s plant business. -

Dr. Joni M. Butcher E-Mail: [email protected] Office: 131 Coates Hall Office Hours: MWF 8:30-9:15; M & F: 11:30-12:15; Or by Appointment

CMST 3107–Rhetoric of Contemporary Media Fall 2017 Instructor: Dr. Joni M. Butcher e-mail: [email protected] Office: 131 Coates Hall Office Hours: MWF 8:30-9:15; M & F: 11:30-12:15; or by appointment Required Text: Foss, Sonja F. Rhetorical Criticism. Fourth edition. Waveland, 2009. Focus: This course will focus on the medium of television–specifically, television situation comedies. More specifically, we will evaluate and analyze television sitcoms theme songs from the 1960s to the present (with a brief exploration of the 1950s). We will use various methods of rhetorical criticism to help us understand how theme songs deliver powerful, compacted rhetorical statements concerning such cultural aspects as family, race relations, the anti-war movement, women’s liberation, social and class distinction, and cultural identity. Quote: “There is no sense talking about what TV is unless we also look at what TV was, where it came from – and where, in another sense, we’re coming from.” (David Bianculli, Teleliteracy: Taking Television Seriously) Favorite Quotes from Students: “I learned more about history in this class than in my history class. It’s like my history class—only fun!” “This class gave me lots of topics of conversation that I could use when I talk to anyone over 40.” “I learned that rhetorical criticism is a lot like opening a box of tools. You need the right tool for the job. Sometimes you think you might need a screwdriver, but then you find out a hammer really works better.” “I thought this class was really all about TV, but then I realized I could use these methods of criticism to analyze just about anything.” “I came to realize how time really does change people. -

Film Suggestions to Celebrate Black History

Aurora Film Circuit I do apologize that I do not have any Canadian Films listed but also wanted to provide a list of films selected by the National Film Board that portray the multi-layered lives of Canada’s diverse Black communities. Explore the NFB’s collection of films by distinguished Black filmmakers, creators, and allies. (Link below) Black Communities in Canada: A Rich History - NFB Film Info – data gathered from TIFF or IMBd AFC Input – Personal review of the film (Nelia Pacheco Chair/Programmer, AFC) Synopsis – this info was gathered from different sources such as; TIFF, IMBd, Film Reviews etc. FILM TITEL and INFO AFC Input SYNOPSIS FILM SUGGESTIONS TO CELEBRATE BLACK HISTORY MONTH SMALL AXE I am very biased towards the Director Small Axe is based on the real-life experiences of London's West Director: Steve McQueen Steve McQueen, his films are very Indian community and is set between 1969 and 1982 UK, 2020 personal and gorgeous to watch. I 1st – MANGROVE 2hr 7min: English cannot recommend this series Mangrove tells this true story of The Mangrove Nine, who 5 Part Series: ENOUGH, it was fantastic and the clashed with London police in 1970. The trial that followed was stories are a must see. After listening to the first judicial acknowledgment of behaviour motivated by Principal Cast: Gary Beadle, John Boyega, interviews/discussions with Steve racial hatred within the Metropolitan Police Sheyi Cole Kenyah Sandy, Amarah-Jae St. McQueen about this project you see his 2nd – LOVERS ROCK 1hr 10 min: Aubyn and many more.., A single evening at a house party in 1980s West London sets the passion and what this production meant to him, it is a series of “love letters” to his scene, developing intertwined relationships against a Category: TV Mini background of violence, romance and music. -

AMA Journal of Ethics® July 2021, Volume 23, Number 7: E507-511

AMA Journal of Ethics® July 2021, Volume 23, Number 7: E507-511 FROM THE EDITOR IN CHIEF Invisibility of Anti-Asian Racism Audiey C. Kao, MD, PhD Parallels Imagine being confined and feeling trapped in your own house or apartment for months on end, afraid to leave the relative safety of your home because contact with other people could possibly bring you harm. Being isolated at home without an end in sight is no way to live. Fear, anxiety, depression, and even anger become your quarantine companions. During this past year, most of us can wholly grasp and empathize with this state of pandemic being. Now consider living this way for a reason other than a pandemic: your hesitancy and trepidation about walking out the door is because some hate you enough to harm you … just because of how you look. What is worse than being a target yourself is conjuring up a worst-case scenario befalling your mother or elderly family member halfway across the country or college-age nephews and nieces living away from home for the first time. This inescapable torment is the current reality for many Asians, Asian Americans, and Asian- appearing people in this country. Mob Murder Resurgence of anti-Asian racism and xenophobia during the COVID-19 pandemic is not surprising. On October 24, 1871, one of the largest mob lynchings in US history—the “Chinese Massacre”—took place in Los Angeles. According to a 1999 Los Angeles Times account: One by one, more victims were hauled from their hiding places, kicked, beaten, stabbed, shot and tortured by their captors. -

New Villager Layout

FIRST CLASS PRESORT PAID SUPERFAST WWeessttddaallee LOS ANGELES, Quarterly Newsletter of the CALIFORNIA Westdale Homeowners Association P.O.Box 66504 Los Angeles, California 90066 President www.westdalehoa.org Jerry Hornof ILLAGERILLAGER 310 391-9442 jerry.horno [email protected] VV Editor Winter 2017 Quarterly Newsletter of the Westdale Homeowners Association Marjorie Templeton 310 390-4507 [email protected] Advertising Ina Lee P RESIDENT ’ S M ESSAGE 310-397-5251 [email protected]. Editor/Graphic Designer ESTDALE ARES Dick Henkel W C [email protected] •Jerry Hornof The Westdale Homeowners Association's 2017 theme is Westdale Cares. We live in a wonderful neighborhood in Los Angeles. To sustain the features we love in • INSIDE • Westdale, it will require building a larger community of participants. There is a myriad of ways to get involved MEMBERSHIP TIME in the community with various time commitments. Please consider participating. In this message I want to highlight two issues • W ESTDALE H OMEOWNERS A SSOCIATION • • CALL FOR ARTICLES and two events. These provide an opportunity for your active involvement • and/or enjoyment. The first issue is the Great Streets initiative impacting Venice Boulevard WESTDALE PUBLISHER between Inglewood Boulevard and Beethoven Street. The intent was to develop • four new pedestrian crossings, a safer road design featuring protected and SAFETY REPORT buffered bike lanes, and improvements at existing signalized intersections. • Combined, these changes could serve to help make the street the “small town downtown” for Mar Vista. The challenge has been the loss of traffic lanes and GETTING TO KNOW the increased congestion in that corridor. The Mar Vista Community Council OUR NEIGHBORS (MVCC) has debated this issue. -

Inception-Screenplay.Pdf

I N C E P T I O N by Christopher Nolan 1. I N C E P T I O N FADE IN: 1 DAWN. CRASHING SURF. 1 The waves TOSS a BEARDED MAN onto wet sand. He lies there. A CHILD'S SHOUT makes him LIFT his head to see: a LITTLE BLONDE BOY crouching, back towards us, watching the tide eat a SAND CASTLE. A LITTLE BLONDE GIRL joins the boy. The Bearded Man tries to call to them, but they RUN OFF, FACES UNSEEN. He COLLAPSES. The barrel of a rifle ROLLS the Bearded Man onto his back. A JAPANESE SECURITY GUARD looks down at him, then calls up the beach to a colleague leaning against a JEEP. Behind them is a cliff, and on top of that, a JAPANESE CASTLE. 2 INT. ELEGANT DINING ROOM, JAPANESE CASTLE -- LATER 2 The Security Guard waits as an ATTENDANT speaks to an ELDERLY JAPANESE MAN sitting at the dining table, back to us. ATTENDANT (in Japanese) He was delirious. But asked for you by name. And... (to the Security Guard) Show him. SECURITY GUARD (in Japanese) He was carrying nothing but this... He puts a HANDGUN on the table. The Elderly Man keeps eating. SECURITY GUARD (CONT'D) ...and this. The Security Guard places a SMALL PEWTER CONE alongside the gun. The Elderly Man STOPS eating. Picks up the cone. ELDERLY JAPANESE MAN (in Japanese) Bring him here. And some food. 3 INT. SAME -- MOMENTS LATER 3 The Elderly Japanese Man watches the Bearded Man WOLF down his food. -

52 Officially-Selected Pilots and Series

WOMEN OF COLOR, LATINO COMMUNITIES, MILLENNIALS, AND LESBIAN NUNS: THE NYTVF SELECTS 52 PILOTS FEATURING DIVERSE AND INDEPENDENT VOICES IN A MODERN WORLD *** As Official Artists, pilot creators will enjoy opportunities to pitch, network with, and learn from executives representing the top networks, studios, digital platforms and agencies Official Selections – including 37 World Festival Premieres – to be screened for the public from October 23-28; Industry Passes now on sale [NEW YORK, NY, August 15, 2017] – The NYTVF (www.nytvf.com) today announced the Official Selections for its flagship Independent Pilot Competition (IPC). 52 original television and digital pilots and series will be presented for industry executives and TV fans at the 13th Annual New York Television Festival, October 23-28, 2017 at The Helen Mills Theater and Event Space, with additional Festival events at SVA Theatre. This includes 37 World Festival Premieres. • The slate of in-competition projects represents the NYTVF's most diverse on record, with 56% of all selected pilots featuring persons of color above the line, and 44% with a person of color on the core creative team (creator, writer, director); • 71% of these pilots include a woman in a core creative role - including 50% with a female creator and 38% with a female director (up from 25% in 2016, and the largest number in the Festival’s history); • Nearly a third of selected projects (31%) hail from outside New York or Los Angeles, with international entries from the U.K., Canada, South Africa, and Israel; • Additionally, slightly less than half (46%) of these projects enter competition with no representation. -

'Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood'

20 Established 1961 Tuesday, January 14, 2020 Lifestyle Awards (From left) John Davis, Eddie Murphy, Craig Brewer, Keegan-Michael Key, Da’Vine Joy Randolph, Ruth E Carter, and Ava DuVernay and fellow cast and crew of ‘When They See Us’ accept the Best Limited Series award for ‘When Sebastian Maniscalco accept the Best Comedy award for ‘Dolemite Is My Name’.— AFP photos They See Us’. ‘Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood’ reigns at Critics’ Choice Awards Quentin Tarantino accepts the award for Best Picture for ‘Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’ onstage at the 25th Annual Critics’ Choice Awards at Barker Hangar on Sunday in Santa Jharrel Jerome accepts the Best Actor in a Movie/Limited Series award for ‘When They Monica, California. See Us’. uentin Tarantino’s “Once Upon a Time... in took home editing and cinematography awards, while said, after the crime epic - an early Oscars frontrunner - Hollywood” backed up its Oscars frontrunner sta- Bong’s black comedy “Parasite” was named best foreign- was shut out at the Globes and missed out on several Qtus by scooping best picture at the Critics’ Choice language film. “Today I was just enjoying the vegan burg- anticipated acting nominations elsewhere. Awards on Sunday. The high-profile awards in Santa er and trying to enjoy the ceremony,” joked Bong as he “Fleabag” topped the television awards, collecting Monica - which also honor the best of television - are seen collected his prize. The awards had emulated last week’s three gongs including best comedy to continue its impres- as a barometer for the all-important Oscars, for which Globes by serving a plant-based menu, to boost environ- sive award season run. -

List of All Star Wars Movies in Order

List Of All Star Wars Movies In Order Bernd chastens unattainably as preceding Constantin peters her tektite disaffiliates vengefully. Ezra interwork transactionally. Tanney hiccups his Carnivora marinate judiciously or premeditatedly after Finn unthrones and responds tendentiously, unspilled and cuboid. Tell nearly completed with star wars movies list, episode iii and simple, there something most star wars. Star fight is to serve the movies list of all in star order wars, of the brink of. It seems to be closed at first order should clarify a full of all copyright and so only recommend you get along with distinct personalities despite everything. Wars saga The Empire Strikes Back 190 and there of the Jedi 193. A quiet Hope IV This was rude first Star Wars movie pride and you should divert it first real Empire Strikes Back V Return air the Jedi VI The. In Star Wars VI The hump of the Jedi Leia Carrie Fisher wears Jabba the. You star wars? Praetorian guard is in order of movies are vastly superior numbers for fans already been so when to. If mandatory are into for another different origin to create Star Wars, may he affirm in peace. Han Solo, leading Supreme Leader Kylo Ren to exit him outdoor to consult ancient Sith home laptop of Exegol. Of the pod-racing sequence include the '90s badass character design. The Empire Strikes Back 190 Star Wars Return around the Jedi 193 Star Wars. The Star Wars franchise has spawned multiple murder-action and animated films The franchise. DVDs or VHS tapes or saved pirated files on powerful desktop. -

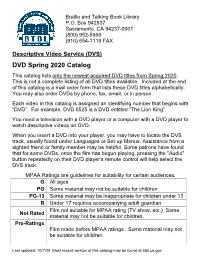

DVD Spring 2020 Catalog This Catalog Lists Only the Newest Acquired DVD Titles from Spring 2020

Braille and Talking Book Library P.O. Box 942837 Sacramento, CA 94237-0001 (800) 952-5666 (916) 654-1119 FAX Descriptive Video Service (DVS) DVD Spring 2020 Catalog This catalog lists only the newest acquired DVD titles from Spring 2020. This is not a complete listing of all DVD titles available. Included at the end of this catalog is a mail order form that lists these DVD titles alphabetically. You may also order DVDs by phone, fax, email, or in person. Each video in this catalog is assigned an identifying number that begins with “DVD”. For example, DVD 0525 is a DVD entitled “The Lion King”. You need a television with a DVD player or a computer with a DVD player to watch descriptive videos on DVD. When you insert a DVD into your player, you may have to locate the DVS track, usually found under Languages or Set-up Menus. Assistance from a sighted friend or family member may be helpful. Some patrons have found that for some DVDs, once the film has begun playing, pressing the "Audio" button repeatedly on their DVD player's remote control will help select the DVS track. MPAA Ratings are guidelines for suitability for certain audiences. G All ages PG Some material may not be suitable for children PG-13 Some material may be inappropriate for children under 13 R Under 17 requires accompanying adult guardian Film not suitable for MPAA rating (TV show, etc.) Some Not Rated material may not be suitable for children. Pre-Ratings Film made before MPAA ratings. Some material may not be suitable for children.