Sierra Nevada Framework FEIS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Native Trout Waters of California Details Six of the State’S Most Scenic, Diverse, and Significant Native Trout Fisheries

NATIVE TROUT WATERS OF CALIFORNIA Michael Carl The Ecological Angler www.ecoangler.com TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUTION – THE ORIGINAL SIX 4 ABOUT THE BOOK 4 CLAVEY RIVER 5 BACKGROUND 6 TROUT POPULATION DATA 6 STREAM POPULATIONS, REGULATIONS, AND ACCESS 7 DIRECTIONS TO REACH SEGMENT 3 AND 4 (E.G., BRIDGE CROSSING CLAVEY RIVER): 7 AREA MAP 8 CLAVEY RIVER FLOW STATISTICS 9 FISHING TECHNIQUES 9 EAGLE LAKE 10 BACKGROUND 11 BIG TROUT FOOD – TUI CHUBS 11 REGULATIONS AND ACCESS 11 DIRECTIONS TO EAGLE LAKE FROM RED BLUFF, CALIFORNIA: 11 AREA MAP 12 PRODUCTIVE TIMES AND ZONES TO FISH 13 FISHING TECHNIQUES 13 SPALDING TRACT – TOPO MAP 14 PIKES POINT – TOPO MAP 15 GOLDEN TROUT CREEK 16 OVERVIEW OF THE WATERSHED 17 ABUNDANCE OF CALIFORNIA GOLDEN TROUT 17 CALIFORNIA GOLDEN TROUT GENETIC DATA 17 STREAM POPULATIONS, REGULATIONS, AND ACCESS 18 DIRECTIONS TO COTTONWOOD PASS TRAILHEAD 18 AREA MAP 19 PHOTO JOURNAL – COTTONWOOD PASS TO TUNNEL MEADOW 20 FISHING TECHNIQUES 23 HEENAN LAKE 24 BACKGROUND 25 FLY ANGLER STATISTICS – 2007 SEASON (8/3/07 TO 10/28/07) 26 REGULATIONS AND ACCESS 27 AREA MAP 27 DIRECTIONS 27 PRODUCTIVE ZONES TO FISH 28 FISHING TECHNIQUES 28 UPPER KERN RIVER 29 BACKGROUND 30 KERN RIVER RAINBOWS 30 DISTRIBUTION OF KERN RIVER RAINBOWS 30 STREAM POPULATIONS, REGULATIONS AND ACCESS 31 MAP – LLOYD MEADOW ROAD TO FORKS OF THE KERN 32 SPOTLIGHT – FORKS OF THE KERN 33 DIRECTIONS AND TRAIL DESCRIPTION 33 RECOMMENDED FISHING GEAR 33 UPPER TRUCKEE RIVER 35 OVERVIEW OF THE WATERSHED 36 ABUNDANCE AND SIZE OF LAHONTAN CUTTHROAT 37 STREAM POPULATIONS, REGULATIONS, ACCESS & DISTANCE 37 DIRECTIONS TO REACH TRAILHEAD: 38 AREA MAP 39 TRAIL DESCRIPTION 40 FISHING TECHNIQUES 40 Introduction – The Original Six The Native Trout Waters of California details six of the state’s most scenic, diverse, and significant native trout fisheries. -

Caspian Tern Nesting Island Construction Draft Supplemental

Draft Supplemental Environmental Assessment (with Draft Amended FONSI) and Clean Water Act Section 404(b)(1) Alternatives Analysis Caspian Tern Nesting Island Construction Project Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge Siskiyou and Modoc Counties, California U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Portland District June 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Proposed Project 1.1 Proposed Project Description 1.2 Proposed Location 1.3 Purpose and Need for Proposed Action 1.4 Project Authority 2.0 Scope of Analysis 3.0 Proposed Action 3.1 Habitat Construction: Sheepy Lake in Lower Klamath NWR 3.1.1 Demolition and Disposal of Sheepy Floating Island 3.1.2 Sheepy Rock Island Design 3.1.3 Timing of Construction 3.1.4 Construction Methods 3.1.5 Access 3.1.6 Staging Area 3.1.7 Temporary Access Road 3.1.8 Maintenance Methods 3.1.9 Summary of Fill Requirements and Footprint 3.1.10 Post-Construction Monitoring 4.0 Alternatives 4.1 No Action Alternative 4.2 Repair the existing floating island 5.0 Impact Assessment 6.0 Summary of Indirect and Cumulative Effects 6.1 Indirect Effects 6.1.1 Caspian Terns 6.1.2 Fishes 6.1.3 Endangered and Threatened Species 6.1.4 Other Birds 6.1.5 Socioeconomic Effects 6.2 Cumulative Impacts 7.0 Environmental Compliance 8.0 Agencies Consulted and Public Notifications 9.0 Mitigation Measures 10.0 Draft Amended FONSI LIST OF FIGURES 1.1 Map of Tule Lake NWR and Lower Klamath NWR within the vicinity of Klamath Basin NWRs, Oregon and California 3.1 Sheepy Lake Floating Island Failure (1 of 3) 3.2 Sheepy Lake Floating Island Failure (2 of 3) 3.3 -

Fire Codes Used in the Kern River Valley

i The Kern River Valley Community Fire Safe Plan Created by HangFire Environmental for the Kern River Fire Safe Council and the citizens they strive to protect. October 2002 The Kern River Valley Community Fire Safe Plan was funded by a grant to the Kern River Valley Fire Safe Council by the United States Department of Agriculture-Forest Service, National Fire Plan-Economic Action Program. In accordance with Federal law and United States Department of Agriculture policy, Kern River Valley Fire Safe Council in cooperation with the Kern River Valley Revitalization Incorporated is prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, or disability. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs). To file a complaint of discrimination, write the United States Department of Agriculture, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue,. SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202)720-5964 (voice or TDD). The United States Department of Agriculture-Forest Service is an equal opportunity provider and employer. ii Table of Contents Kern River Valley Community Wildfire Protection Plan................................................................i The Kern River Valley Community Fire Safe Plan........................................................................ii Table of Contents...........................................................................................................................iii Introduction.....................................................................................................................................1 -

The Native Trouts of the Genus Salmo of Western North America

CItiEt'SW XHPYTD: RSOTLAITYWUAS 4 Monograph of ha, TEMPI, AZ The Native Trouts of the Genus Salmo Of Western North America Robert J. Behnke "9! August 1979 z 141, ' 4,W \ " • ,1■\t 1,es. • . • • This_report was funded by USDA, Forest Service Fish and Wildlife Service , Bureau of Land Management FORE WARD This monograph was prepared by Dr. Robert J. Behnke under contract funded by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and the U.S. Forest Service. Region 2 of the Forest Service was assigned the lead in coordinating this effort for the Forest Service. Each agency assumed the responsibility for reproducing and distributing the monograph according to their needs. Appreciation is extended to the Bureau of Land Management, Denver Service Center, for assistance in publication. Mr. Richard Moore, Region 2, served as Forest Service Coordinator. Inquiries about this publication should be directed to the Regional Forester, 11177 West 8th Avenue, P.O. Box 25127, Lakewood, Colorado 80225. Rocky Mountain Region September, 1980 Inquiries about this publication should be directed to the Regional Forester, 11177 West 8th Avenue, P.O. Box 25127, Lakewood, Colorado 80225. it TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preface ..................................................................................................................................................................... Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. -

Research, Monitoring, and Evaluation of Avian Predation on Salmonid Smolts in the Lower and Mid‐Columbia River

Bonneville Power Administration, USACE – Portland District, USACE – Walla Walla District, and Grant County Public Utility District Research, Monitoring, and Evaluation of Avian Predation on Salmonid Smolts in the Lower and Mid‐Columbia River 2013 Draft Annual Report 1 2013 Draft Annual Report Bird Research Northwest Research, Monitoring, and Evaluation of Avian Predation on Salmonid Smolts in the Lower and Mid‐Columbia River 2013 Draft Annual Report This 2013 Draft Annual Report has been prepared for the Bonneville Power Administration, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and the Grant County Public Utility District for the purpose of assessing project accomplishments. This report is not for citation without permission of the authors. Daniel D. Roby, Principal Investigator U.S. Geological Survey ‐ Oregon Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit Department of Fisheries and Wildlife Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon 97331‐3803 Internet: [email protected] Telephone: 541‐737‐1955 Ken Collis, Co‐Principal Investigator Real Time Research, Inc. 52 S.W. Roosevelt Avenue Bend, Oregon 97702 Internet: [email protected] Telephone: 541‐382‐3836 Donald Lyons, Jessica Adkins, Yasuko Suzuki, Peter Loschl, Timothy Lawes, Kirsten Bixler, Adam Peck‐Richardson, Allison Patterson, Stefanie Collar, Alexa Piggott, Helen Davis, Jen Mannas, Anna Laws, John Mulligan, Kelly Young, Pam Kostka, Nate Banet, Ethan Schniedermeyer, Amy Wilson, and Allison Mohoric Department of Fisheries and Wildlife Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon 97331‐3803 2 2013 Draft Annual Report Bird Research Northwest Allen Evans, Bradley Cramer, Mike Hawbecker, Nathan Hostetter, and Aaron Turecek Real Time Research, Inc. 52 S.W. Roosevelt Ave. Bend, Oregon 97702 Jen Zamon NOAA Fisheries – Pt. -

Conservation Status of Threatened Fishes in Warner Basin, Oregon

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 50 Number 3 Article 5 10-31-1990 Conservation status of threatened fishes in arnerW Basin, Oregon Jack E. Williams Division of Wildlife and Fisheries, Bureau of Land Management, Washington, D.C. Mark A. Stern The Nature Conservancy, Portland, Oregon Alan V. Munhall Bureau of Land Management, Lakeview, Oregon Gary A. Anderson Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Lakeview, Oregon Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Williams, Jack E.; Stern, Mark A.; Munhall, Alan V.; and Anderson, Gary A. (1990) "Conservation status of threatened fishes in arnerW Basin, Oregon," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 50 : No. 3 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol50/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Creat &Isio N:l.luraUst 50(3), 1900, pp. 243-248 CONSERVATION STATUS OF THREATENED FISHES IN WARNER BASIN, OREGON 1 l 3 Jack E. Williams , MarkA. Stern \ Alan V. Munhall , and Cary A. Anderson"" A8S'TRACT.-Two fedemlJy listed fisbes, the Foskett speckled daceand Warnersucker, are endemic to Warner Basin in south central Oregon. The Foskett speckled dace is native only to a single spring in Coleman Valley. Anearby'spring was stocked with dace in 1979 and 1980, and now provides a second population. The present numbers ofdace probably are at their Wgbest levels since settlement ofthe region. -

Standards for Rangeland Health Assessment O'keeffe FRF

ee e_ O'KEEFFE FRF INDIVIDUAL ALLOTMENT #0203 Standards for Rangeland Health and Guidelines for Livestock Grazing Management (BLM, 1997) Introduction The Range Reform '94 Record of Decision (BLM, 1995a) recently amended current grazing administration and management practices. The ROD required that region-specific standards and guidelines be developed and approved by the Secretary of the Interior. In the State of Oregon, several Resource Advisory Councils (RACs) were established to develop these regional standards and guidelines. The RAC established for the part of the state covering the O'Keeffe FRF Individual Allotment is the Southeastern Oregon RAe. These standards and guidelines for Oregon and Washington were finalized on August 12, 1997 and include: Standard 1 - Upland Watershed Function Upland soils exhibit infiltration and permeability rates, moisture storage, and stability that are appropriate to soil, climate, and landform. • dard 2 - Riparian/Wetland Watershed Function • Riparian-wetland areas are in properly functioning physical condition appropriate to soil, climate, and landform. Standard 3 - Ecological Processes Healthy, productive, and diverse plant and animal populations and communities appropriate to soil, climate, and landform are supported by ecological processes of nutrient cycling, energy flow, and the hydrologic cycle. Standard 4 - Water Quality Surface water and groundwater quality, influenced by agency actions, complies with State water quality standards. Standard 5 - Native, T&E, and Locally Important Species Habitats support healthy, productive, and diverse populations and communities of native plants and animals (including special status species and species of local importance) appropriate to soil, climate, and landform. NDARD 1 - UPLAND WATERSHED CONDITION: Upland soils exhibit infiltration and permeability rates, moisture storage, and stability that are appropriate to soil, climate, and landform. -

Forest Order 0513-21-09 Kern River Ranger

ORDER NO. 0513-21-09 SEQUOIA NATIONAL FOREST KERN RIVER RANGER DISTRICT KERN CANYON AND ISABELLA LAKE GLASS CONTAINER PROHIBITION Pursuant to 16 U.S.C. § 551 and 36 C.F.R. § 261.50(a), and to provide for public safety, the following act is prohibited within the Kern River Ranger District of the Sequoia National Forest. This Order is effective from May 1, 2021 through April 30, 2023. Possessing or storing food or beverages in glass containers in the Kern Canyon and Isabella Lake Glass Container Prohibition Areas, as described on Exhibit A, and shown on Exhibits B, C, and D. 36 C.F.R. § 261.58(cc). Pursuant to 36 C.F.R. § 261.50(e), the following persons are exempt from this Order: Any Federal, State, or local officer, or member of an organized rescue or fire fighting force in the performance of an official duty. This prohibition is in addition to the general prohibitions in 36 C.F.R. Part § 261, Subpart A. A violation of this prohibition is punishable by a fine of not more than $5,000 for an individual or $10,000 for an organization, or imprisonment for not more than six months, or both. 16 U.S.C. § 551 and 18 U.S.C. §§ 3559, 3571, and 3581. Done at Porterville, California, this 13th day of April, 2021. TERESA BENSON Forest Supervisor Sequoia National Forest ORDER NO. 0513-21-09 SEQUOIA NATIONAL FOREST KERN RIVER RANGER DISTRICT KERN CANYON AND ISABELLA LAKE GLASS CONTAINER PROHIBITION EXHIBIT A The Kern Canyon and Isabella Lake Glass Container Prohibition Area is comprised of three segments. -

Wilderness Study Areas

I ___- .-ll..l .“..l..““l.--..- I. _.^.___” _^.__.._._ - ._____.-.-.. ------ FEDERAL LAND M.ANAGEMENT Status and Uses of Wilderness Study Areas I 150156 RESTRICTED--Not to be released outside the General Accounting Wice unless specifically approved by the Office of Congressional Relations. ssBO4’8 RELEASED ---- ---. - (;Ao/li:( ‘I:I)-!L~-l~~lL - United States General Accounting OfTice GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 Resources, Community, and Economic Development Division B-262989 September 23,1993 The Honorable Bruce F. Vento Chairman, Subcommittee on National Parks, Forests, and Public Lands Committee on Natural Resources House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: Concerned about alleged degradation of areas being considered for possible inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System (wilderness study areas), you requested that we provide you with information on the types and effects of activities in these study areas. As agreed with your office, we gathered information on areas managed by two agencies: the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management (BLN) and the Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service. Specifically, this report provides information on (1) legislative guidance and the agency policies governing wilderness study area management, (2) the various activities and uses occurring in the agencies’ study areas, (3) the ways these activities and uses affect the areas, and (4) agency actions to monitor and restrict these uses and to repair damage resulting from them. Appendixes I and II provide data on the number, acreage, and locations of wilderness study areas managed by BLM and the Forest Service, as well as data on the types of uses occurring in the areas. -

Federal Register/Vol. 75, No. 37/Thursday, February 25, 2010

Federal Register / Vol. 75, No. 37 / Thursday, February 25, 2010 / Proposed Rules 8621 We encourage interested parties to DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Wildlife Office, 2600 SE. 98th Avenue, continue to gather data that will assist Suite 100, Portland, OR 97266; with the conservation of the species. If Fish and Wildlife Service telephone 503–231–6179; facsimile you wish to provide information 503–231–6195. regarding the bald eagle, you may 50 CFR Part 17 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Paul submit your information or materials to [Docket No. FWS–R1–ES–2008–0128] Henson, Ph.D., State Supervisor, U.S. the Field Supervisor, Arizona Ecological [MO 92210–0–0009–B4] Fish and Wildlife Service, Oregon Fish ADDRESSES and Wildlife Office (see ADDRESSES, Services Office (see section RIN 1018–AW72 above). The Service continues to above). Persons who use a strongly support the cooperative Endangered and Threatened Wildlife telecommunications device for the deaf conservation of the Sonoran Desert Area and Plants; Withdrawal of Proposed (TDD) may call the Federal Information bald eagle. Rule To List the Southwestern Relay Service (FIRS) at 800–877–8339. On March 6, 2008, the U.S. District Washington/Columbia River Distinct SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Court for the District of Arizona Population Segment of Coastal Background enjoined our application of the July 9, Cutthroat Trout (Oncorhynchus clarki clarki) as Threatened On July 5, 2002, we published a 2007 (72 FR 37346), final delisting rule notice of our withdrawal of the for bald eagles to the Sonoran Desert AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, proposed rule to list the Southwestern population pending the outcome of our Interior. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

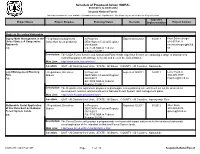

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2012 to 03/31/2012 Sequoia National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2012 to 03/31/2012 Sequoia National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Gypsy Moth Management in the - Vegetation management In Progress: Expected:03/2012 01/2013 Noel Schneeberger United States: A Cooperative (other than forest products) DEIS NOA in Federal Register 610-557-4121 Approach 09/19/2008 [email protected]. EIS Est. FEIS NOA in Federal us Register 12/2011 Description: The USDA Forest Service and Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service are analyzing a range of strategies for controlling gypsy moth damage to forests and trees in the United States. Web Link: http://www.na.fs.fed.us/wv/eis/ Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. Nationwide. Land Management Planning - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2011 12/2011 Larry Hayden Rule Orders DEIS NOA in Federal Register 202-205-1559 EIS 02/25/2011 [email protected] Est. FEIS NOA in Federal Register 11/2011 Description: The Department of Agriculture proposes to promulgate a new planning rule, which will set out the process for development, revision, and amendment of National Forest System land management plans. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/planningrule Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. Agency-wide Rule. Nationwide Aerial Application - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2011 01/2012 Glen Stein of Fire Retardant on National Orders DEIS NOA in Federal Register 208-869-5405 Forest System Lands.