The Wheathampstead Workhouse: a Speculative History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning and Tree Works Applications

ST ALBANS DISTRICT COUNCIL PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED WEEK ENDING 2ND OCTOBER 2015 THREE WEEK PERIOD EXPIRES 23RD OCTOBER 2015 (COUNCILLOR CALL-IN PERIOD) Information regarding Councillor call-in period and procedure for public consultation. Comments and call-ins may be made on any Advertisement Consent, Listed Building, Conservation Area, Householder, Certificate of Lawfulness (existing), Telecommunication and Planning Applications please e.mail: [email protected] (Please include the Application No (e.g. "5/2009/1234") in the title of the e.mail) Application No 5/2015/2610 Ward: Ashley Area: C Proposal: Erection of rear conservatory at 8 Longacres St Albans Hertfordshire AL4 0DR Applicant: Agent: Mr & Mrs Jolles 8 Longacres St Britelite Windows Mr Steve Nash Britelite Albans Hertfordshire AL4 0DR House Bircholt Road Parkwood Maidstone Kent ME15 9XY http://planning.stalbans.gov.uk/Planning/lg/dialog.page?org.apache.shale.dialog.DIALOG_NAME=gfplanningsearch&Param=lg.Planning&ref_no=5/2015/2610 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Application No 5/2015/2627 Ward: Ashley Area: C Proposal: Single storey rear extension, garage conversion and alterations to car port to form garage at 19a Marconi Way St Albans Hertfordshire AL4 0JG Applicant: Agent: Mr & Mrs Katarzyna Pawel Ratajczak GK Architects Limited Mr Kryspin Skorek 19a Marconi Way St Albans Vicarage House 58-60 Kensington Church Hertfordshire AL4 0JG Street London W8 4DB http://planning.stalbans.gov.uk/Planning/lg/dialog.page?org.apache.shale.dialog.DIALOG_NAME=gfplanningsearch&Param=lg.Planning&ref_no=5/2015/2627 -

Luton to Hatfield 366 Via Luton Parkway - Harpenden - Wheathampstead - Welwyn Garden City

Centrebus From 29 March 2020 Luton to Hatfield 366 via Luton Parkway - Harpenden - Wheathampstead - Welwyn Garden City Monday to Friday Service No 366 366 366 366 366 366 366 366 366 366 366 366 Sch SH Luton, Interchange 0606 0710 ..... 0922 1022 1122 1222 1322 1422 1502 1522 1725 Luton, Church St 0609 0713 ..... 0925 1025 1125 1225 1325 1425 1505 1525 1728 Luton Airport Parkway 0613 0720 ..... 0931 1031 1131 1231 1331 1431 1511 1531 1734 New Mill End 0617 0725 ..... 0936 1036 1136 1236 1336 1436 1516 1536 1739 East Hyde 0619 0727 ..... 0938 1038 1138 1238 1338 1438 1518 1538 1741 0622 0731 ..... 0942 1042 1142 1242 1342 1442 1522 1542 1745 Roundwood Park School ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... 1530 ..... ..... Harpenden, High Street 0627 0738 ..... 0949 1049 1149 1249 1349 1449 1538 1549 1751 Harpenden, Rail Station 0629 0740 ..... 0951 1051 1151 1251 1351 1451 1541 1551 1753 Batford, The Malta 0632 0745 ..... 0955 1055 1155 1255 1355 1455 1546 1555 1757 Marshalls Heath, Cherry Trees 0635 0749 ..... 0959 1059 1159 1259 1359 1459 1550 1559 1801 Wheathampstead, High Street 0753 ..... 1004 1104 1204 1304 1404 1504 1554 1604 1805 Wheathampstead, Hilldyke Rd, Vale Co ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... 1558 ..... ..... Lemsford Village 0645 0801 ..... 1011 1111 1211 1311 1411 1511 1609 1611 1813 Valley Road 0647 0805 ..... 1013 1113 1213 1313 1413 1513 1611 1613 1816 Welwyn Garden City, Bus Station arr 0649 0810 ..... 1017 1117 1217 1317 1417 1517 1614 1617 1820 Welwyn Garden City, Bus Station dep 0650 0815 0920 1020 1120 1220 1320 1420 1520 1620 1620 ..... Heronswood Rd, Salisbury Rd 0654 0819 0924 1024 1124 1224 1324 1424 1524 1624 1624 .... -

Down Green House Down Green House Harpenden Road | Wheathampstead | St Albans | Hertfordshire | AL4 8ED

Down Green House Down Green House Harpenden Road | Wheathampstead | St Albans | Hertfordshire | AL4 8ED Harpenden High Street with mainline station (St Pancras International from 22 minutes) - 2.3 miles, St Albans City with mainline station (St Pancras International from 18 minutes) - 4.8 miles, Central London – 26.6 miles, Wheathampstead village centre - 1 mile, A1M - 4.5 miles, M1(J.9) - 6 miles, London Luton Airport - 6.4 miles A substantial Grade II Listed country house with excellent leisure facilities, fabulous far reaching views, all set in grounds totalling 8.6 acres SUMMARY OF ACCOMMODATION ENTRANCE HALL | SITTING ROOM | STUDY/OFFICE | LIBRARY | ORANGERY | SUN ROOM | SNUG KITCHEN | BREAKFAST AREA | UTILITY ROOM | 2 CLOAKROOMS | CELLAR MASTER BEDROOM WITH DRESSING ROOM | EN SUITE BATH & SHOWER ROOM & SPIRAL STAIRCASE DOWN TO ORANGERY BEDROOM 2 WITH EN SUITE BATHROOM | BEDROOM 3 WITH EN SUITE BATHROOM & DRESSING AREA 2 FURTHER BEDROOMS | FAMILY BATHROOM FORMAL GARDENS WITH SUN TERRACE AND BUILT IN BBQ EXTENSIVE GROUNDS WITH ADJOINING RING FENCED PADDOCK, LARGE TIMBER FRAMED OUTBUILDING/GARAGING, IN ALL 8.620 ACRes (3.489 HA) LEISURE AREA INDOOR HEATED SWIMMING POOL | GYMNASIUM | SAUNA / SHOWER / CHANGING ROOM | PLAY ROOM | MUSIC ROOM Savills Savills Harpenden Country House Department [email protected] [email protected] 01582 465000 0207 4998644 Situation The historic village of Wheathampstead lies about 1 mile away, whilst the town of Harpenden lies 2.3 miles to the east and St Albans 4.8 miles to the south. Wheathampstead offers a good range of day to day shops, pubs and a Tesco Express, whilst Harpenden, with its distinctly village feel, offers a range of supermarkets, numerous boutiques and traditional independent shops, restaurants, bars and bistros. -

Working Children of St Michael's, St Albans, 1851

WORKING CHILDREN OF ST MICHAEL’S, ST ALBANS, 1851 Introduction Peter Kirby, in his book ‘Child Labour in Britain,’ states that “very few children below 10 were ever engaged in productive labour”, and he therefore focuses his book on 10-14 year olds. 1 Unfortunately, nineteenth century summary census data is only provided in 5 year age bands. Thus it is able to show that nearly 30% of 10-14 year olds and 2% of 5-9 year olds in England and Wales were recorded as employed in 1851,2 but does not indicate the proportion for individual year groups. A casual glance at the 1851 census returns for St Michael’s shows that there were many children under the age of 10 who were working, some as young as 7, and that by age 12, the majority were working. This paper therefore focuses on 7-12 year olds, to determine the proportion of each year group who were working and the nature of their occupation. It is based on the census returns for St Michael’s urban enumeration district, which includes all the houses in the Parish and Borough, including part of Fishpool Street, St Michael’s and Pound Field. In 1851 there were 224 households and 1091 residents. Numbers of Working Children in St Michael’s urban 1851 Table 1 shows the numbers and percentages of working children in St Michael’s by year group. It can be seen that some boys and girls were at work by the age of 7, but that this was a minority. -

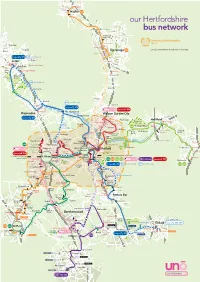

Uno Herts Network Map MASTER A3 UH Zone

Sainsbury’s Hitchin Walsworth Waitrose Road Queens St Asda Hitchin 635 Park St London Rd A602 A1(M) our Hertfordshire A602 Sainsbury’s Lister Hosptal bus network A602 Martins Way A1(M) Stevenage Old Town L y High St n t University of Hertfordshire o n Fairlands Way W zone 1 a Barnfield y Tesco Stevenage Monkswood Way Stopsley 635 zone 2 is everywhere else shown on this map Biscot Asda Stevenage North Hertfordshire College school days only 610 612 Stevenage FC Wigmore A602 A602 Luton Tesco B roa Luton NON STOP dw ate The Mall London Luton Airport r Cres Park Town A1(M) Matalan New Luton Airport Parkway Town Knebworth London Rd Capability Knebworth Stockwood Park Green B653 612 school days only Luton Hoo East Hyde Oaklands A1081 A1(M) L Welwyn NON STOP ut on R d Batford 612 school days only Sainsbury’s Lower Luton Rd Digswell 610 Station Rd Waitrose 601 653 Harpenden High St Wheathampstead Harpenden St Albans Rd l Welwyn Garden City l i Bro Marford Rd ck H Marshalls Heath s wood Ln Oaklands College e A1(M) 610 h B653 T H e Panshanger Hertford ro n Panshanger Welwyn Garden sw Hertford East o Park A414 City od R Cromer d 612 d Road Hertford h R Hyde Ln Green g Broadwater Hertingfordbury London Rd A1081 u 641 North Gascoyne school days only ro Peartree Way o High St b n Hall Grove ta HCC County Hall S Ho s Birch Green Hertford wland Cole Bullocks Lane Heath en Ln Stanborough Chequers Gre New QEII Green Sandridge rs Lakes Rd Ware pe Hospital London Rd oo C Mill tford Rd Cavan Drive Hatfield Ave Green Her St Albans Rd Jersey Farm Tesco Sandringham -

HERTFORDSHIRE. CAR 909 Moulden Joseph Samuel, Stevenage Tompkins C.Jun.High St.Gt.Berkhmstd CAKE & BISCUIT MAKERS

TRADES DIRECTORY.] HERTFORDSHIRE. CAR 909 Moulden Joseph Samuel, Stevenage Tompkins c.jun.High st.Gt.Berkhmstd CAKE & BISCUIT MAKERS. Neale Frederick, 22 Langley rd. Watfrd Tompkins Fras.High st. Gt.Berkhamstd Far-Famed Cake Co. (John Williams, New Zealand Meat Co. (Richard Wright, TompkinsJ.I8High st. IiemelHempstead" manager), London H manager, 148 High street, Watford TompkinsThos. High st.Gt.Berkhamstd CANDLE MANUFACTURERS Newman Wm. Wormley, Broxbourne S. 0 TurnerJn.TwoWaters,HemelHempstead . Nicholls Wm. Tho~. High st. Hoddesdon Turner WaIter, High street, Hoddesdon WIles E. S. & Co.; office, George street; Nickels James, 4 Henry rd. New Barnet Waby William, Stevenage works, Bernards heath, St. Albans NottageW.W.Wormley,Broxbourne S.O Walby Mrs. Esther S. Park st. Hatfield OANVAS MANUFACTURERS. Oakley John, L~ttimore,rd. St. Albans ,,:alby Ja!D~' Codicote, Welwyn Cato Charles, Charles street, Tring Outlaw Ge~. HJ~h. st. Gt. Be~kh~msted "\\,alby Wllbam, Graveley, Ste,:en¥e Cato George Park road TrinO' Owney Damel, Umon road, Hltcbm "alker John, Queen street, Hltchm " '" Oxbrow Mrs. Arthur, Market square, Walker Josepb Gray, High st. Barnet CARMEN. Bisbop's Stortford Warrell Jas. 9 Maidenhead st. Hertford Atkins Henry, Grange st. St. Albans Parkins Charles, Collier's end, Ware WatersE.90 Marlowes, HemelHempstead Ballard Benjamin, Station, Buntingford Parrott Edward, High street, Ware Watkins Joseph, lIB High st. Watford Bassell George, 5 Albert st. St. Albans Parslo~ John, Frogmo~e street, Tring Webb J~~~ Sim~i~s, Fore st. Hat.fiel~ Boyce George, Alexandra rd. St. Albans Pate MISS Jane, Turner s hIll, Chesbunt, Webb "\\llham, '" bmbush road, Hltchm Brice A. -

Welwyn Garden City - Hatfield 366 MONDAYS to FRIDAYS from 18Th January 2021 Notes

Temporary Timetable for duration of the Covid-19 crisis, to operate until further notice Centrebus Luton - Welwyn Garden City - Hatfield 366 MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS from 18th January 2021 Notes: Luton, Station Interchange, Stand 8 0652 0922 1122 1322 1527 Luton, Church Street, Stop C9 0655 0925 1125 1325 1530 Luton Airport Parkway Railway Station 0701 0931 1131 1331 1536 Newmill End, Chiltern Green Road 0706 0936 1136 1336 1541 E Hyde, Lwr Harpenden Road, Hambro Close 0708 0938 1138 1338 1543 Harpenden, Westfield Rd, opp Red Cow PH 0712 0942 1142 1342 1547 Harpenden, High St, The George, Stop D 0717 0947 1147 1347 1552 Harpenden Railway Station, Stop B a 0719 0949 1149 1349 1554 Batford, Lower Luton Road, The Malta PH 0722 0952 1152 1352 1557 Marshalls Heath, opp Cherry Trees Rest 0726 0956 1156 1356 1601 Wheathampstead, opp St Helen's Church 0730 1000 1200 1400 1605 Lemsford Village, opp The Sun PH 0737 1007 1207 1407 1612 W G City, Valley Rd, opp Applecroft Rd 0739 1009 1209 1409 1614 Welwyn Garden City, Bus Station, Stop E a 0742 0920 1012 1020 1120 1212 1320 1412 1420 1520 1617 1620 W G City, Heronswood Rd, Salisbury Rd (SE) 0924 1024 1124 1324 1424 1524 1624 Welwyn Garden City, New QEII Hospital, Stop A 0930 1030 1130 1330 1430 1530 1630 Hatfield Railway Station, Stop 1 a 0938 1038 1138 1338 1438 1538 1638 Hatfield, Town Centre, Stop W 0941 1041 1141 1341 1441 1541 1641 Oxlease, Travellers Lane, Oxlease Drive 0943 1043 1143 1343 1443 1543 1643 South Hatfield, Travellers Lane, Millwards 0946 1046 1146 1346 1446 1546 1646 South Hatfield, -

Nomansland Common Leaflet

Common Lizard Common them. on feed that birds the and mark the parish boundary. parish the mark important for butterflies and other insects, insects, other and butterflies for important to used was stone pudding Hertfordshire Sunny woodland paths and glades are also also are glades and paths woodland Sunny should share the grazing rights and a boulder of of boulder a and rights grazing the share should Finally in 1429, a jury agreed that the parishes parishes the that agreed jury a 1429, in Finally years of disputes. of years between the two warring factions, with over twenty twenty over with factions, warring two the between The Common acted as the ‘no-mans-land’ ‘no-mans-land’ the as acted Common The Dwarf Gorse Dwarf the Common for their respective parish. respective their for Common the Honeysuckle contested both Westminster and Albans St of monasteries the Century 15 the During th Black Knapweed Black parishes, Sandridge and Wheathampstead. Wheathampstead. and Sandridge parishes, Nomansland Common lies across two two across lies Common Nomansland Why Nomansland? Why Woodpecker Green Green eared Bat eared Linnet on a Sunday afternoon. afternoon. Sunday a on Brown Long- Brown flying and families who enjoy a picnic picnic a enjoy who families and flying Beetle walking, horse riding, model aircraft aircraft model riding, horse walking, Ground Ground dog for space open popular rare insects. rare Today Nomansland Common is a very very a is Common Nomansland Today and fungi specialist great for hibinating bats, bats, hibinating for great try to enclose the land for their own private farms. -

Marford Farm

MARFORD FARM SHEEPCOTE LANE, WHEATHAMPSTEAD, ST ALBANS, HERTFORDSHIRE AL4 8NJ A CHARMING PERIOD FARMHOUSE WITH EXCELLENT RANGE OF OUTBUILDINGS AND SELF CONTAINED ANNEXE, SET IN GARDENS AND GROUNDS OF ABOUT 2.5 ACRES. marford farm, sheepcote lane, wheathampstead, st albans, hertfordshire al4 8nj w Lovely exposed timbers to reception rooms w Large kitchen/breakfast room w Versatile living space w Self contained annexe, perfect for dependant relative or working from home w Attached timber framed barn with potential to convert (STPP) w Further range of useful outbuildings w Extensive gardens w Separate paddock, ideal for those with an equestrian interest w River frontage w Extensive parking and detached double garage Mileage Harpenden town centre with mainline station 3.5 miles – St Pancras International from 22 minutes St Albans City Centre with mainline station 4.8 miles Welwyn Garden City centre with mainline station 5 miles – London Kings Cross from 30 minutes M1 (J 9) 7.0 miles London Luton Airport 7.9 miles Description Situated at the end of a quiet no-through road and backing on to the River Lea, you would be forgiven to think that you are in the middle of the countryside. However, being just 3.5 miles from Harpenden and 4.8 miles from St Albans, Marford Farm offers the ‘country feel’ with the London connection. The farmhouse offers great scope if one needed to have space to work from home, a dependent relative to look after or just wanting to utilise the great range of barns for recreational purposes. The formal and informal gardens offer great space for children and for entertaining guests and a large paddock to the east of the house offers grazing for livestock, or for those with an equine interest. -

For Sale by Informal Tender,Barton House, 17-19, Brewhouse Hill

For Sale by Informal Tender Prominent Grade II Listed Building Conversion Opportunity Barton House, 17-19, Brewhouse Hill, Wheathampstead, AL4 8AN • 330.9 Sq M (3,532 Sq Ft) • Suitable for conversion for a variety of uses (subject to obtaining all necessary consents) • Additional basement area of 195.6 sq m (2,116 sq ft) • Offers invited by 12noon on 31st Oct 2018 Lambert Smith Hampton 45 Grosvenor Road, St Albans AL1 3AW T +44 (0)1727 834234 Barton House, 17-19, Brewhouse Hill, Wheathampstead, AL4 8AN Location Legal Costs Each party to be responsible for their own legal costs incurred in any transaction. The purchaser will be liable for any stamp duty land tax that may fall due as a result of a sale. Town Planning Interested parties should make any town planning enquiries of St Albans Council (Local Planning Authority) on 01727 866160. Planning permission (now expired) was approved on 31st October 2000 (ref: 5/2000/1799) for conversion of the property to two residential dwellings. Offers Wheathampstead is a large village within the City and Interested parties are invited to submit offers by way of District of St Albans with a population of 6,410 (2011 an informal tender. The Sellers preference is for census). It is situated approximately five miles to the unconditional offers. north of St Albans via the B651, five miles to the west of Welwyn Garden City via the B653 and seven miles to the Offers should be submitted no later than 12 noon on south east of Luton, also via the B653. -

6302 the London Gazette, 20 November, 1953

6302 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 20 NOVEMBER, 1953 NATIONAL PARKS AND ACCESS TO THE COUNTRYSIDE ACT, 1949 HERTFORDSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL Public Rights of Way NOTICE is hereby given that the County Council of the Administrative County of Hertford, in accordance with the provisions of Part IV of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act, 1949, have prepared a draft map and statement showing the public paths and roads used as public paths within that part of the said County which is comprised in the undermentioned county districts. A copy of the draft map and statement may be inspected at the office of the County Surveyor at County Hall, Hertford, during the usual office hours and copies of so much thereof as relates to each of the undermentioned county districts and parishes may also be inspected during the usual office hours at the places mentioned below. Representations or objections with respect to the draft map and statement may be sent in writing to the Clerk of the County Council at County Hall, Hertford, within four months of the date of the publication of this notice. Any such representation or objection should state the grounds on which it is made. Names of County Districts Places where appropriate extracts from the draft map and Parishes and statement may be inspected. Hemel Hempstead Borough Town Hall, Hemel Hempstead. City of St. Albans 38, St. Peters Street, St. Albans. Watford Borough Town Hall, Watford. Berkhamsted Urban District Civic Centre, Berkhamsted. Tring Urban District Council Offices, Tring. Harpenden Urban District Council Offices, Harpenden Hall. Chorleywood Urban District Chorleywood House. -

12 Manor Road, Wheathampstead, Hertfordshire AL4 8JD a Significantly Extended Semi Detached Family Home with Four Bedrooms, Two Bathrooms and a Large Rear Garden

12 Manor Road, Wheathampstead, Hertfordshire AL4 8JD A significantly extended semi detached family home with four bedrooms, two bathrooms and a large rear garden. 12 Manor Road Wheathampstead, Hertfordshire Price guide £675,000 Wheathampstead centre 1.6 Miles GROUND FLOOR, Porch, Entrance Hall, Living Room, Family Room, Kitchen/Dining Room, FIRST FLOOR, Harpenden Station 1.5 miles on foot Landing, Bedroom One, En-Suite Shower Room, Bedroom Two, Bedroom Three, Bedroom Four, Bathroom, (St Pancras fast train 27 minutes) EXTERNALLY, Frontage, Rear Garden St Albans City Centre 6.1 Miles London Luton Airport 6.8 Miles M1 (J9) 6.2 Miles A1M (J4) 6.1 Miles THE HOUSE AND GARDENS This much improved house occupies a quiet position away from main roads and has an entrance lobby leading through to an entrance hall with built-in double cloak cupboard and cloakroom beneath the stairs incorporating a low flush WC and wash hand basin. The attractive living room is graced with stripped pine floors and an open fireplace making this very inviting and a window to the front incorporating louvred shutters. A wide opening leads through to the kitchen/dining room. This has bi-fold doors providing a panoramic look over the rear garden, whilst the kitchen area is fitted with a range of wall mounted and floor standing storage units, a four ring hob with extractor unit above, recess suitable for an American style fridge/freezer, built-in oven, stainless steel sink unit and plumbing for automatic washing machine. The family room is a really versatile entertaining space for the children or a cosy escape for parents and has sliding patio doors opening to the rear garden.