Writing Processes of Musical Theater Writers: How They Create a Storyline, Compose Songs, and Connect Them to Form a Musical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer 2018 Edition Thresholdpublished SINCE 1963

News from Envision | Summer 2018 Edition thresholdPUBLISHED SINCE 1963 Envision Celebrates 55 Years of Service Leadership Still Planning and Vision-Casting Things were different in 1963. Stu Warshauer described it in jaw-drop- ping terms during a May 11 speech at Envision’s Emerald Gala where he was honored, along with the late Bernie Esterkamp, for his role as one of the founders of the Resident Home for the Mentally Retarded (RHMR) – which was re-named “Envision” in 2013. The former Proctor & Gamble marketing Stu Warshauer (standing in B&W photo) provided early leadership that is now being continued by President executive told the stunned gala attend- & CEO, Jim Steffey (standing in color photo), and his executive leadership team (from left to right): Chris ees: “Our doctors and clergy said: ‘Don’t Bohn, CFO; Katie Pursifull, Director of Human Resources; and Anne Rule, Director of Supported Living. bring the baby home from the hospital. You might get attached to it.’” CEO, Jim Steffey, and his executive lead- support from individuals, foundations ership team, are navigating waters with and corporations,” said Jim. Don’t bring the baby home? You might get new challenges as they fix their sight on attached? What was common in 1963 the future horizon. Increasing community inclusion of the seems unfathomable in 2018. nearly 600 children and adults served Stagnant reimbursement rates from the by Envision and expanding services east Stu, Bernie and other early visionaries federal Medicaid program, Envision’s of downtown Cincinnati are two current did get attached and got busy creating a primary funding source, is one of the goals. -

The Enduring Power of Musical Theatre Curated by Thom Allison

THE ENDURING POWER OF MUSICAL THEATRE CURATED BY THOM ALLISON PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY NONA MACDONALD HEASLIP PRODUCTION CO-SPONSOR LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Welcome to the Stratford Festival. It is a great privilege to gather and share stories on this beautiful territory, which has been the site of human activity — and therefore storytelling — for many thousands of years. We wish to honour the ancestral guardians of this land and its waterways: the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Wendat, and the Attiwonderonk. Today many Indigenous peoples continue to call this land home and act as its stewards, and this responsibility extends to all peoples, to share and care for this land for generations to come. CURATED AND DIRECTED BY THOM ALLISON THE SINGERS ALANA HIBBERT GABRIELLE JONES EVANGELIA KAMBITES MARK UHRE THE BAND CONDUCTOR, KEYBOARD ACOUSTIC BASS, ELECTRIC BASS, LAURA BURTON ORCHESTRA SUPERVISOR MICHAEL McCLENNAN CELLO, ACOUSTIC GUITAR, ELECTRIC GUITAR DRUM KIT GEORGE MEANWELL DAVID CAMPION The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. A MESSAGE FROM OUR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WORLDS WITHOUT WALLS Two young people are in love. They’re next- cocoon, and now it’s time to emerge in a door neighbours, but their families don’t get blaze of new colour, with lively, searching on. So they’re not allowed to meet: all they work that deals with profound questions and can do is whisper sweet nothings to each prompts us to think and see in new ways. other through a small gap in the garden wall between them. Eventually, they plan to While I do intend to program in future run off together – but on the night of their seasons all the plays we’d planned to elopement, a terrible accident of fate impels present in 2020, I also know we can’t just them both to take their own lives. -

Southern Comfort

FROM THE NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MUSICAL THEAtre’s PresideNT Welcome to our 24th Annual Festival of New Musicals! The Festival is one of the highlights of the NAMT year, bringing together 600+ industry professionals for two days of intense focus on new musical theatre works and the remarkably talented writing teams who create them. This year we are particularly excited not only about the quality, but also about the diversity—in theme, style, period, place and people—represented across the eight shows that were selected from over 150 submissions. We’re visiting 17th-century England and early 20th century New York. We’re spending some time in the world of fairy tales—but not in ways you ever have before. We’re visiting Indiana and Georgia and the world of reality TV. Regardless of setting or stage of development, every one of these shows brings something new—something thought-provoking, funny, poignant or uplifting—to the musical theatre field. This Festival is about helping these shows and writers find their futures. Beyond the Festival, NAMT is active year-round in supporting members in their efforts to develop new works. This year’s Songwriters Showcase features excerpts from just a few of the many shows under development (many with collaboration across multiple members!) to salute the amazing, extraordinarily dedicated, innovative work our members do. A final and heartfelt thank you: our sponsors and donors make this Festival, and all of NAMT’s work, possible. We tremendously appreciate your support! Many thanks, too, to the Festival Committee, NAMT staff and all of you, our audience. -

Passporttothearts

Cedar Falls, Iowa Falls, Cedar ___________________________________ Email ___________________________________ Phone ___________________________________ Name This passport belongs to: belongs passport This PASSPORT Enjoy a summer vacation without even leaving Cedar Falls! RULES? Numerous arts organizations are offering a variety of Yes, rules. Sorry. They’re pretty easy though… events—most of which are free—for your enjoyment. Get this passport stamped at a minimum 1 A minimum of six stamps from three organizations are of six events and become eligible to receive required—two for month—this means two in June, July a prize package valued at $260! and August. No repeated organizations are allowed in the same month. For example two Movies Under the Moon in June would not be allowed, however you can use one in PARTICIPATING PARTNERS: June and one in July. 2 It’s your responsibility to get your passport stamped at the events. Signage with the Passport to the Arts logo will direct you to the “stamping” station. 3 Turn your completed passport in to the Hearst Center for the Arts, Community Main Street office, or Cedar Falls Tourism and Visitors Bureau office. You may also bring your completed passport to Artapalooza. This is, however, not a Cedar Falls MUNICIPAL stampable event. A drawing from completed passports will BAND take place at the Hearst Center kids tent located near the corner of 2nd and Main Streets at 10am. Participants are invited to attend, however you need not be present to win. COMMUNICATION PARTNERS: QUESTIONS? Additional information can be found at CedarFallsTourism.org/PassportToTheArts. Or contact Sheri Huber-Otting at the Hearst Center for the Arts, [email protected], or 319-268-5502. -

Ouachita Students Myers and Walls to Perform Sophomore Recitals Oct

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Press Releases Office of Communication 10-19-2016 Ouachita students Myers and Walls to perform sophomore recitals Oct. 28 Ouachita News Bureau Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/press_releases Part of the Higher Education Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, and the Public Relations and Advertising Commons For immediate release Ouachita students Myers and Walls to perform sophomore recitals Oct. 28 By OBU News Bureau October 19, 2016 For more information, contact OBU’s news bureau at [email protected] or (870) 245-5208. ARKADELPHIA, Ark. — Ouachita Baptist University will host Zachary Myers and Cody Walls for their sophomore musical theatre recitals on Friday, Oct. 28, at 11 a.m. in McBeth Recital Hall. The recitals are free and open to the public. Myers, from Greenwood, Ark., and Walls, from Fort Smith, Ark., both are musical theatre majors. They are students of Dr. Glenda Secrest, professor of music, and Drew Hampton, assistant professor of theatre arts. Phyllis Walker, OBU staff accompanist, will provide piano accompaniment for both performances. Walls will open his recital with Jule Styne and Stephen Sondheim’s “All I Need Is the Girl” from Gypsy, followed by “What You Mean to Me” from Finding Neverland by Eliot Kennedy, David Lindsay- Abaire’s Rabbit Hole and “Caught in the Storm” by Benj Pasek and Justin Paul. Lisa Lambert and Greg Morrison’s “I Am Aldolpho” from The Drowsy Chaperone will close his recital. Mackenzie Osborne, a sophomore musical theatre major from Heath, Texas, helped choreograph the recital and will perform with Walls during a portion of the performance. -

Duncan Stewart, CSA and Benton Whitley, CSA, Casting Directors

Duncan Stewart, CSA and Benton Whitley, CSA, Casting Directors/Partners Paul Hardt, Christine McKenna-Tirella, CSA Casting Director Ian Subsara, Emily Ludwig Casting Assistant Resume as of 3.15.2019 _________________________________________________________________ CURRENT & ONGOING: HADESTOWN Theater, Broadway – Walter Kerr Theater March 2019 – Open Ended Mara Isaacs, Hunter Arnold, Dale Franzen (Prod.) Rachel Chavkin (Dir.), David Newmann (Choreo.) By: Anais Mitchell CHICAGO THE MUSICAL Theater, Broadway – Ambassador Theater May 2008 – Open Ended Barry and Fran Weissler (Prod.) Walter Bobbie (Dir.), Ann Reinking (Choreo.) By: John Kander & Fred Ebb CHICAGO THE MUSICAL Theater, West End – Phoenix Theater March 2018 – Open Ended Barry and Fran Weissler (Prod.) Walter Bobbie (Dir.), Ann Reinking (Choreo.) By: John Kander & Fred Ebb ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY PLAYLIST NBC Lionsgate TV Pilot March 2019 Richard Shepard (Dir.), Austin Winsberg (Writer) NY Casting AUGUST RUSH Theater, Regional – Paramount Theater January 2019 – June 2019 Paramount Theater (Prod.) John Doyle (Dir.), JoAnn Hunter (Choreo.) By: Mark Mancina, Glen Berger, David Metzger PARADISE SQUARE: An American Musical Theater, Regional – Berkeley Repertory Theatre December 2018 – March 2019 Garth Drabinsky (Prod.) ________________________________________________________________________ 1 Stewart/Whitley 213 West 35th Street Suite 804 New York, NY 10001 212.635.2153 Moisés Kaufman (Dir.), Bill T. Jones (Choreo.) By: Marcus Gardley, Jason Howland, Larry Kirwan, Craig Lucas, Nathan -

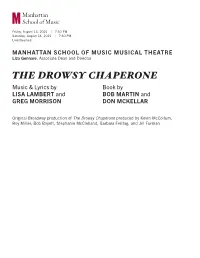

THE DROWSY CHAPERONE Music & Lyrics by Book by LISA LAMBERT and BOB MARTIN and GREG MORRISON DON MCKELLAR

Friday, August 13, 2021 | 7:30 PM Saturday, August 14, 2021 | 7:30 PM Livestreamed MANHATTAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC MUSICAL THEATRE Liza Gennaro, Associate Dean and Director THE DROWSY CHAPERONE Music & Lyrics by Book by LISA LAMBERT and BOB MARTIN and GREG MORRISON DON MCKELLAR Original Broadway production of The Drowsy Chaperone produced by Kevin McCollum, Roy Miller, Bob Boyett, Stephanie McClelland, Barbara Freitag, and Jill Furman Friday, August 13, 2021 | 7:30 PM Saturday, August 14, 2021 | 7:30 PM Livestreamed MANHATTAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC MUSICAL THEATRE Liza Gennaro, Associate Dean and Director THE DROWSY CHAPERONE Music & Lyrics by Book by LISA LAMBERT and BOB MARTIN and GREG MORRISON DON MCKELLAR Original Broadway production of The Drowsy Chaperone produced by Kevin McCollum, Roy Miller, Bob Boyett, Stephanie McClelland, Barbara Freitag and Jill Furman Evan Pappas, Director Liza Gennaro, Choreographer David Loud, Music Director Dominique Fawn Hill, Costume Designer Nikiya Mathis, Wig, Hair, and Makeup Designer Kelley Shih, Lighting Designer Scott Stauffer, Sound Designer Megan P. G. Kolpin, Props Coordinator Angela F. Kiessel, Production Stage Manager Super Awesome Friends, Video Production Jim Glaub, Scott Lupi, Rebecca Prowler, Jensen Chambers, Johnny Milani The Drowsy Chaperone is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.mtishows.com STREAMING IS PRESENTED BY SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT WITH MUSIC THEATRE INTERNATIONAL (MTI) NEW YORK, NY. All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.mtishows.com WELCOME FROM LIZA GENNARO, ASSOCIATE DEAN AND DIRECTOR OF MSM MUSICAL THEATRE I’m excited to welcome you to The Drowsy Chaperone, MSM Musical Theatre’s fourth virtual musical and our third collaboration with the video production team at Super Awesome Friends—Jim Glaub, Scott Lupi and Rebecca Prowler. -

Musical Theatre Production Repertoire

ASU LYRIC OPERA THEATRE - MUSICAL THEATRE REPERTOIRE Show Title Creative Team Year(s) Performed 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee, The Composer(s): William Finn 2010 Lyricist(s): William Finn Book Writer(s): Rachel Sheinkin A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum Composer(s): Stephen Sondheim 1969, 78, 89 Lyricist(s): Stephen Sondheim Book Writer(s): Burt Shevelove, Larry Gelbart A Little Night Music Composer(s): Stephen Sondheim 1987, 99 Lyricist(s): Stephen Sondheim Book Writer(s): Hugh Wheeler A...My Name is Alice Composer(s): Various 1991, 98 Lyricist(s): Various Book Writer(s): Joan Silver & Julianne Boyd And the World Goes 'Round Composer(s): John Kander 1994, 2008 Lyricist(s): Fred Ebb Book Writer(s): Revue Anything Goes Composer(s): Cole Porter 2005 Lyricist(s): Cole Porter Book Writer(s): Guy Bolton, P.G. Wodehouse archy and mehitabel Composer(s): George Kleinsinger 1966, 74 Lyricist(s): Joe Darion Book Writer(s): Joe Darion, Don Marquis Assassins Composer(s): Stephen Sondheim 2007 Lyricist(s): Stephen Sondheim Book Writer(s): John Weidman Bat Boy: The Musical Composer(s): Laurence O'Keefe 2012 Lyricist(s): Laurence O'Keefe Book Writer(s): Keythe Farley, Brian Flemming Berlin to Broadway with Kurt Weill Composer(s): Kurt Weill 1977 Lyricist(s): Various Book Writer(s): Gene Lerner Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, The Composer(s): Carol Hall 2011 Lyricist(s): Carol Hall Book Writer(s): Larry L. King, Peter Masterson Boyfriend, The Composer(s): Sandy Wilson 1967, 98, 2005 Lyricist(s): Sandy Wilson Book Writer(s): Sandy -

HAL LEONARD POTPOURRI Saturday, June 30, 1:00 PM NATS Conference 2013, Orlando

HAL LEONARD POTPOURRI Saturday, June 30, 1:00 PM NATS Conference 2013, Orlando Beverly O’Regan Thiele, soprano ● Steven Stolen, tenor ● Kurt Ollmann, baritone Richard Walters, pianist and presenter ● Joan Frey Boytim, presenter The Program Oesterreichischer Soldatenabschied Erich Korngold from the publication Lieder aus dem Nachlass, Band II (posthumous songs, first edition) Kurt Ollmann End of the Line John Corigliano from the song set Metamusic Beverly O’Regan Thiele Video Documentary of The Hal Leonard Vocal Competition Finishing the Hat from Sunday in the Park with George Stephen Sondheim from the publication Musical Theatre for Classical Singers, Tenor and also from the forthcoming The Songs of Stephen Sondheim (in 5 volumes, fall 2012 release) I Am Aldolpho from The Drowsy Chaperone Lisa Lambert, Greg Morrison from the publication Musical Theatre for Classical Singers, Tenor Steven Stolen True Loves Rufus Wainwright from the song cycle Songs For Lulu Kurt Ollmann Joan Boytim presents her new publication, 36 More Solos for Young Singers L’Archet Claude Debussy from the publication Quatre nouvelles mélodies (first edition) Beverly O’Regan Thiele Selections from Minicabs (minicabaret songs) William Bolcom from the publication William Bolcom: Theatrical Songs I Feel Good Food Song #1 Those I Will Never Forgive You Maxim Food Song #2 Beverly O’Regan Thiele, Kurt Ollmann, Steven Stolen Known for her consummate acting and clear, silver-toned, warm voice, Iowa native BEVERLY O’REGAN THIELE is among the best in her field for her interpretation of contemporary opera and equally at home in the classics, concert and recital work. Her successes include Magda Sorel in The Consul, which she sang with Washington National Opera as well as with Berkshire Opera, and recorded the role on the Newport Classics Label. -

SUMMER 2006 Valdy, Jim Vallance, Nancy White Contents SUMMER 2006 Volume 9 Number 2 COVER PHOTO: ANTHONY MANDLER PHOTO: MUCHMUSIC Features

President’s Message EDITOR Nick Krewen The 50% Solution MANAGING EDITOR Beverly Hardy LAYOUT Lori Veljkovic ix years ago, when I first sion to allow two American satellite addressed the S.A.C. annual gen- services into Canada and letting them Canadian Publications Mail Agreement eral meeting as President, I get away with playing as little as 15% No. 40014605 S Canada Post Account No. 02600951 CanCon was devastating. We hope began by mentioning the ancient ISSN 1481-3661 ©2002 Chinese curse, "May you live in inter- that the CRTC may have sharpened Songwriters Association of Canada esting times." their focus this time out. Subscriptions: Canada $16/year plus Well curse or not, things have cer- Looking forward, there are many GST; USA/Foreign $22 tainly been interesting. Perhaps the changes afoot here at the S.A.C.. First Songwriters Magazine is a publication of the last six years have seen the most music of all, I am very pleased to announce Songwriters Association of Canada (S.A.C.) industry upheaval since the advent of the appointment of our new and is published four times a year. Members radio when the industry, then thriv- Executive Director, Don Quarles. of S.A.C. receive Songwriters Magazine as Don comes to us with vast experience part of their membership. Songwriters ing on the sales of piano rolls and 78s, Magazine welcomes editorial comment. cried "The sky is falling!" because as a coordinator and planner of Opinions expressed in Songwriters Magazine music was being played free for any- entertainment events, working both do not necessarily represent the opinions of one who owned a radio. -

Sunset Playhouse Production History 2020-21 Season Run for Your Wife

Sunset Playhouse Production History 2020-21 Season Run for your Wife by Ray Cooney presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French 9 to 5, The Musical by Dolly Parton presented by special arrangement with MTI Elf by Thomas Meehan & Bob Martin presented by special arrangement with MTI 4 Weddings and an Elvis by Nancy Frick presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French The Cemetery Club by Ivan Menchell presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French Young Frankenstein by Mel Brooks presented by special arrangement with MTI An Inspector Calls by JB Priestley presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French Newsies by Harvey Fierstein presented by special arrangement with MTI _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 2019-2020 Season A Comedy of Tenors – by Ken Ludwig presented by special arrangement with Samuel French Mamma Mia – presented by special arrangement with MTI The Game’s Afoot – by Ken Ludwig presented by special arrangement with Samuel French The Marvelous Wonderettes – by Roger Bean presented by special arrangement with StageRights, Inc. Noises Off – by Michael Frayn presented by special arrangement with Samuel French Cabaret – by Joe Masteroff presented by special arrangement with Tams-Witmark Barefoot in the Park – by Neil Simon presented by special arrangement with Samuel French (cancelled due to COVID 19) West Side Story – by Jerome Robbins presented by special arrangement with MTI (cancelled due to COVID 19) 2018-2019 Season The Man Who Came To Dinner – by Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Mary Poppins - Original Music and Lyrics by Richard M. -

30, 2010 Merry-Go-Round Playhouse Music

June 9 - 30, 2010 Merry-Go-round Playhouse Ed Sayles, Producing Director presents Music and Lyrics by Lisa Lambert & Greg Morrison Book by Bob Martin & Don McKellar With Robert Moss*, Julie Cardia*, Geno Carr*, Sandra Karas*, Bethany Moore*, Brad Nacht*, Michael VanGemert & Bruce Warren* Directed by Ed SaylES Musical Director Choreographer CorinnE aquilina lori lEShnEr Scenic Designer Lighting Designer Costume Designer Rob andrusko Adam Frank Travis lope Production Stage Manager Hair and Make-Up Designer Becky lynn dawson* Jason Flanders *Member of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. Musical synopsis The Setting – A New York City Apartment The Time – The Present act i Prologue Overture .................................................................Man in the Chair Scene 1 – Tottendale’s Entrance hall -- Morning Fancy Dress ....................... Mrs. Tottendale, Underling & Company Scene 2 – robert’s room – Morning Cold Feets ................................................ Robert, George and Man Scene 3 – Tottendale’s Pool – Early afternoon Show Off ...............................................................Janet & Company Scene 4 – Entrance hall – afternoon Scene 5 – Janet’s Bridal Suite – afternoon As We Stumble Along ................................. The Drowsy Chaperone Aldolpho .............................................................Aldolpho & Drowsy Scene 6 – Tottendale’s Garden – afternoon Accident Waiting to Happen ....................................