Navigating Our Relationship with Music in the Age of Spotify

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daft Punk Collectible Sales Skyrocket After Breakup: 'I Could've Made

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayFEBRUARY 25, 2021 Page 1 of 37 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Daft Punk Collectible Sales Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debutsSkyrocket at No. 1 on Billboard’s lion audience After impressions, Breakup: up 16%). Top Country• Spotify Albums Takes onchart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earned$1.3B 46,000 in equivalentDebt album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cording• Taylor to Nielsen Swift Music/MRCFiles Data. ‘I Could’veand total Made Country Airplay No.$100,000’ 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideHer Own marks Lawsuit Hunt’s in second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chartEscalating and fourth Theme top 10. It follows freshman LP BY STEVE KNOPPER Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- MontevalloPark, which Battle arrived at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He vember 2014 and reigned for nine weeks. To date, followed with the multiweek No. 1s “In Case You In the 24 hours following Daft Punk’s breakup Thomas, who figured out how to build the helmets Montevallo• Mumford has andearned Sons’ 3.9 million units, with 1.4 Didn’t Know” (two weeks, June 2017), “Like I Loved millionBen in Lovettalbum sales. -

SYNCHRONICITY and VISUAL MUSIC a Senior Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Music Business, Entrepreneurship An

SYNCHRONICITY AND VISUAL MUSIC A Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Music Business, Entrepreneurship and Technology The University of the Arts In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF SCIENCE By Zarek Rubin May 9, 2019 Rubin 1 Music and visuals have an integral relationship that cannot be broken. The relationship is evident when album artwork, album packaging, and music videos still exist. For most individuals, music videos and album artwork fulfill the listener’s imagination, concept, and perception of a finished music product. For other individuals, the visuals may distract or ruin the imagination of the listener. Listening to music on an album is like reading a novel. The audience builds their own imagination from the work, but any visuals such as the novel cover to media adaptations can ruin the preexisted vision the audience possesses. Despite the audience’s imagination, music can be visualized in different forms of visual media and it can fulfill the listener’s imagination in a different context. Listeners get introduced to new music in film, television, advertisement, film trailers, and video games. Content creators on YouTube introduce a song or playlist with visuals they edit themselves. The content creators credit the music artist in the description of the video and music fans listen to the music through the links provided. The YouTube channel, “ChilledCow”, synchronizes Lo-Fi hip hop music to a gif of a girl studying from the 2012 anime film, Wolf Children. These videos are a new form of radio on the internet. -

An Innovative Method of Weather Modification Roberto Maglione, Cristian Sotgiu Biometeorology and Space Medicine Institute, Ludes University, Lugano, Switzerland

www.orgonenergy.org il portale italiano dedicato all’orgonomia An Innovative Method of Weather Modification Roberto Maglione, Cristian Sotgiu Biometeorology and Space Medicine Institute, Ludes University, Lugano, Switzerland This paper was presented at the VII International Conference on Cosmos and Biosphere: Cosmic Weather and Biological Process, October 1-6, 2007, Sudak, Crimea, Ukraine Abstract First experimental studies of cloud and fog seeding date back to 1919, where Altberg and colleagues at the Central Physical Observatory in Leningrad started experiments both with ice nucleation in supercooled water and with snowflakes growth; on lab fog production; and on cloud seeding with electrically charged sand. In 1934 the Dutch Veraart performed the first studies on seeding clouds with dry ice. Later on in the 1950s, Vonnegut performed the first experiments by seeding clouds with silver iodide with good results. In the last decades, several operations aimed at producing precipitation, controlling hail damage, dispersing of supercooled fog and clouds over airports, and dispersing clouds cover over large areas were carried out by using chemical agents. Diverting hurricanes path was also performed. However, many often the results that were obtained were contrasting and also sometimes an inversion of the tendency in weather conditions was observed with period of intense drought in areas where rainmaking experiments were previously carried out. In parallel, in the 1950s the Austrian scientist Wilhelm Reich started investigating and experimenting a new method of weather modification aimed at restoring the natural functioning of the atmosphere characterised by periodic cycles of rain and clear weather. The fundamental principle of this method, that was called Cloudbusting, is based on the presence in the atmosphere of a pulsatory cosmic energy (called orgone energy) postulated to be responsible for major atmospheric phenomena. -

12.15.2020 – Taylor Swift, Reinvented Once Again

:: View email as a web page :: So much of our Covid-related discourse in 2020 centered on what was lost. But a precious few of us seized upon this very strange and sequestered year as an opportunity for acquiring some new part of ourselves. Was it a surprise that Taylor Swift was one of those people? Her summer release Folklore was instantly contextualized as a quarantine project. Swift’s second album of 2020, Evermore, was similarly presented by the singer-songwriter herself as extra run-o! from an especially fruitful songwriting period. But anyone taking a wider view of her career could see albums like Folklore and Evermore on Swift’s musical horizon, even before Covid. During the press cycle for her 2019 e!ort Lover, Swift was already expressing disdain for the pop machine, likening it to The Hunger Games. That strain was also apparent on the album, in which some very good “small” Taylor Swift songs were larded with some very bad “big” would-be hits like “Me” and “I Forgot You Existed.” More than ever, the gap between the songs in which Swift’s heart seemed to be truly invested and the songs required for radio exposure and meme-friendly virality was incredibly stark. As our current reigning stadium rocker, Swift had made Born In The U.S.A.-style mega-smashes time and again. Now, it seemed, she yearned to make her Nebraska . But would pop’s chronic overachiever ever allow herself to make an album of strictly “small” and intimate songs? When the world shut down in 2020, the obligation to fill our stadiums and arenas with world- conquering jams suddenly became moot. -

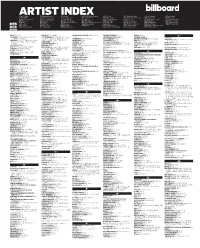

ARTIST INDEX(Continued)

ChartARTIST Codes: CJ (Contemporary Jazz) INDEXINT (Internet) RBC (R&B/Hip-Hop Catalog) –SINGLES– DC (Dance Club Songs) LR (Latin Rhythm) RP (Rap Airplay) –ALBUMS– CL (Traditional Classical) JZ (Traditional Jazz) RBL (R&B Albums) A40 (Adult Top 40) DES (Dance/Electronic Songs) MO (Alternative) RS (Rap Songs) B200 (The Billboard 200) CX (Classical Crossover) LA (Latin Albums) RE (Reggae) AC (Adult Contemporary) H100 (Hot 100) ODS (On-Demand Songs) STS (Streaming Songs) BG (Bluegrass) EA (Dance/Electronic) LPA (Latin Pop Albums) RLP (Rap Albums) ARB (Adult R&B) HA (Hot 100 Airplay) RB (R&B Songs) TSS (Tropical Songs) BL (Blues) GA (Gospel) LRS (Latin Rhythm Albums) RMA (Regional Mexican Albums) CA (Christian AC) HD (Hot Digital Songs) RBH (R&B Hip-Hop) XAS (Holiday Airplay) FEB CA (Country) HOL (Holiday) NA (New Age) TSA (Tropical Albums) CS (Country) HSS (Hot 100 Singles Sales) RKA (Rock Airplay) XMS (Holiday Songs) CC (Christian) HS (Heatseekers) PCA (Catalog) WM (World) CST (Christian Songs) LPS (Latin Pop Songs) RMS (Regional Mexican Songs) 13 CCA (Country Catalog) IND (Independent) RBA (R&B/Hip-Hop) DA (Dance/Mix Show Airplay) LT (Hot Latin Songs) RO (Hot Rock Songs) 2021 $NOT HS 16, 19 BEYONCE STX 14; WM 7 TASHA COBBS LEONARD GA 4, 11, 12, 14; ZACARIAS FERREIRA TSA 17 HOTBOII HS 20 -L- GS 12 21 SAVAGE B200 53; RBA 29; RLP 24; H100 JUSTIN BIEBER B200 187; RBL 24; A40 3, 12, LA FIERA DE OJINAGA RMS 33 STEPHEN HOUGH CL 6 LABRINTH STX 22 100; RBH 36, 38; RP 22 23; AC 7, 11; DA 20, 36; H100 9, 12, 28, 85; COCHREN & CO. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Demeo J. Water As a Resonant Medium for Unusual External

WATER Water as a Resonant Medium for Unusual External Environmental Factors DeMeo J1* 1 Director, Orgone Biophysical Research Laboratory, Ashland, Oregon, USA * Correspondence: E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: structured water, living water, memory of water, bioenergetics, cosmic ether, plasma, interstellar medium, dark matter, Chi, orgone Received March 1, 2011; Accepted March 31, 2011; Published May 18, 2011; Available Online July 1, 2011 doi: 10.14294/WATER.2011.3 Summary a water-affecting cosmic medium, typically being more active at higher altitudes, often During the last Century multiple lines of tangibly interacting with dielectrical mat- converging evidence indicated the existence ter and being reflected by metals. All were of a dynamic plasmatic energy existing marginalized or maligned by the scientific within living organisms and water, and also orthodoxy of their day. I successfully rep- as a background medium filling the atmo- licated some of the anomalous biological, sphere and vacuum of space. Experimenters physical and meteorological experiments such as Jacque Benveniste (memory of wa- of Reich, among others, and so have been ter), Frank Brown (external biological clock able to ascertain important similarities in mechanism), Harold Burr (electrodynam- their diverse findings. Taken together these ic fields), Dayton Miller (cosmic ether of studies are suggestive of a major scientific space), Bjorn Nordenstrom (bio-electrical breakthrough, of a unitary cosmic-biolog- circuits), Giorgio Piccardi (physical-chemi- ical energy phenomenon, ignored or dis- cal fields), Wilhelm Reich (bio-energy) and missed prematurely during the 20th Cen- Viktor Schauberger (living water) indepen- tury. dently measured a similar and unique cos- mic-biological energy phenomenon. -

2013 Kansas City Results

22001133 RReeggiioonnaall RReessuullttss Kansas City, MO Feb 15, 2013 - Feb 17, 2013 Teen Mr. StarQuest Jaymes Dickinson - Pieces Don't Fit Anymore - Priscilla and Dana's School of Dance Mr. StarQuest Alex Gicinto - Holding On - Priscilla and Dana's School of Dance Petite Miss StarQuest Ella Thowe - Without You - Priscilla and Dana's School of Dance Junior Miss StarQuest Katie Rhodus - Let Me Entertain You - Priscilla and Dana's School of Dance Teen Miss StarQuest Aliza Russell - Dancing On My Own - Priscilla and Dana's School of Dance Miss StarQuest Hayley Erbert - Broadway Baby - Priscilla and Dana's School of Dance Top Select Petite Solo 1st Place - Ella Thowe - Without You - Priscilla and Dana's School of Dance 2nd Place - Noel Busch - In Control - Priscilla and Dana's School of Dance 3rd Place - Kamdyn Wedel - Rock Star - PowerHouse Dance 4th Place - Heather Thomas - Eye On The Sparrow - Excel Performing Arts 5th Place - Isabella Cascone - Mambo Italiano - Priscilla and Dana's School of Dance Top Select Junior Solo 1st Place - Katie Rhodus - To Build A Home - Priscilla and Dana's School of Dance 2nd Place - Alaina Lee - Unstoppable - PowerHouse Dance 3rd Place - Annie Riffel - Shelter - Priscilla and Dana's School of Dance 4th Place - Sam Amey - Yellow - Priscilla and Dana's School of Dance 5th Place - Hannah Honn - Wallflower - Priscilla and Dana's School of Dance 6th Place - Sarah Waller - Turn To Stone - Priscilla and Dana's School of Dance 7th Place - Mary Deaver - Come Home - Academy of Fine Arts 8th Place - Keegan Ward - Fix -

Eliza Shaddad Album PR

ALBUM PRESS RELEASE The Woman You Want Artist: Eliza Shaddad Album: The Woman You Want Tracks: 1. The Man I Admire 2. Heaven 3. Fine & Peachy 4. The Woman You Want 5. Waiting Game 6. Tired Of Trying 7. In The Morning (Grandmother Song) 8. Now You’re Alone 9. Blossom Release: 16th July 2021 Format: Vinyl / CD / Download For fans of: Phoebe Bridgers, Angel Olsen, Sheryl Crow “Nakedly confessional.” - The FADER “Extremely talented…” - Rolling Stone “Sing me out of my misery any day, Eliza” - NYLON “Shaddad’s voice is mesmerising.” - The Sunday Times Sudanese-Scottish artist Eliza Shaddad prepares to release her remarkable new album The Woman You Want on 16th July 2021 via Rosemundy Records/Wow and Flutter. The album is the culmination of a year’s work and a moving portrait of a truly unique artist. “The Woman You Want is a record of me figuring myself out” Shaddad explains. “I'd been wrestling with the idea of wanting to be a better human, a better woman, a better wife, better friend, better daughter... and not really feeling capable of it... and the so the title, and title song, came out as a direct challenge really, to me, and to the listener.” More than anything, The Woman You Want is Shaddad’s melding of the myriad, kaleidoscopic influences that make this such a vivid listening experience. It’s a reconciliation of culture, identity, the traditional and the brand new. The album was mixed by Grammy Award winner Sam Okell (PJ Harvey/Celeste/Graham Coxon), mastered by Tim Rowkins (Rina Sawayama) and features Micheal Jablonka (Michael Kiwanuka) on guitar. -

SCR115 Enrolled

2017 Regular Session ENROLLED SENATE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 115 BY SENATOR ERDEY A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION To commend Hunter Plake on his many accomplishments and to congratulate him on his outstanding performance and participation on The Voice reality television series. WHEREAS, as a young man of twenty-one years of age, Hunter Plake has begun a meteoric rise in the entertainment industry beginning with the twelfth season of The Voice, a televison reality series that seeks out unsigned singers and provides a competitive venue for undiscovered talent; and WHEREAS, in the "Blind Auditions" segment of the show, he wowed the judges with his show-stopping vocalization of the song, "Carry On", by Fun; and WHEREAS, judges Gwen Stefani, Alicia Keyes, Blake Shelton, and Adam Levine were quite impressed with Hunter's performances and exceptional range, unique vocal arrangements, and the emotional intensity of his delivery; and WHEREAS, Hunter is also the first performer in the history of the series to have two songs reach the Top 30 listing on iTunes charts before the live playoff broadcasts were aired; and WHEREAS, his roots in music run deep; Hunter comes from a music-oriented family; his brother, Dakota, is also a talented musician and vocalist in his own right, and his father, Bud, was a member of a Christian rock band named Brother, Brother; and WHEREAS, Hunter and Dakota have formed their own band named P L A K E with plans to release a single, "Eden", later this year; and WHEREAS, his renditions of "Elastic Heart" by Sia, "With Or Without You" by U2, "Dancing On My Own" by Robyn, and "Love Runs Out" by One Republic have propelled Hunter high into the ether of musical stardom; and WHEREAS, between the audition/selection process and show performances, Hunter has experienced a roller coaster of life-changing events; he married his sweetheart, Bethany, in June 2016, and they established their home in Livingston Parish only to be flooded just two months later; and Page 1 of 2 SCR NO. -

Merchants Of

Introduction The Jews never faced much anti-Semitism in America. This is due, in large part, to the underlying ideologies it was founded on; namely, universalistic interpretations of Christianity and Enlightenment ideals of freedom, equality and opportunity for all. These principles, which were arguably created with noble intent – and based on the values inherent in a society of European-descended peoples of high moral character – crippled the defenses of the individualistic-minded White natives and gave the Jews free reign to consolidate power at a rather alarming rate, virtually unchecked. The Jews began emigrating to the United States in waves around 1880, when their population was only about 250,000. Within a decade that number was nearly double, and by the 1930s it had shot to 3 to 4 million. Many of these immigrants – if not most – were Eastern European Jews of the nastiest sort, and they immediately became vastly overrepresented among criminals and subversives. A 1908 police commissioner report shows that while the Jews made up only a quarter of the population of New York City at that time, they were responsible for 50% of its crime. Land of the free. One of their more common criminal activities has always been the sale and promotion of pornography and smut. Two quotes should suffice in backing up this assertion, one from an anti-Semite, and one from a Jew. Firstly, an early opponent of the Jews in America, Greek scholar T.T. Timayenis, wrote in his 1888 book The Original Mr. Jacobs that nearly “all obscene publications are the work of the Jews,” and that the historian of the future who shall attempt to describe the catalogue of the filthy publications issued by the Jews during the last ten years will scarcely believe the evidence of his own eyes. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind.