17-565 Amicus Brief.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House/Senate District Number Name House 10 John Bell House 17 Frank Iler House 18 Deb Butler House 19 Ted Davis, Jr

House/Senate District Number Name House 10 John Bell House 17 Frank Iler House 18 Deb Butler House 19 Ted Davis, Jr. House 20 Holly Grange House 23 Shelly Willingham House 24 Jean Farmer Butterfield House 26 Donna McDowell White House 27 Michael H. Wray House 28 Larry C. Strickland House 31 Zack Hawkins House 32 Terry Garrison House 33 Rosa U. Gill House 34 Grier Martin House 35 Chris Malone House 36 Nelson Dollar House 37 John B. Adcock House 38 Yvonne Lewis Holley House 39 Darren Jackson House 41 Gale Adcock House 42 Marvin W. Lucas House 43 Elmer Floyd House 44 Billy Richardson House 45 John Szoka House 49 Cynthia Ball House 50 Graig R. Meyer House 51 John Sauls House 52 Jamie Boles House 53 David Lewis House 54 Robert T. Reives, II House 55 Mark Brody House 57 Ashton Clemmons House 58 Amos Quick House 59 Jon Hardister House 60 Cecil Brockman House 62 John Faircloth House 66 Ken Goodman House 68 Craig Horn House 69 Dean Arp House 70 Pat B. Hurley House 72 Derwin Montgomery House 74 Debra Conrad House 75 Donny C. Lambeth House 77 Julia Craven Howard House 82 Linda P. Johnson House 85 Josh Dobson House 86 Hugh Blackwell House 87 Destin Hall House 89 Mitchell Smith Setzer House 90 Sarah Stevens House 91 Kyle Hall House 92 Chaz Beasley House 95 John A. Fraley House 96 Jay Adams House 97 Jason R. Saine House 98 John R. Bradford III House 102 Becky Carney House 103 Bill Brawley House 104 Andy Dulin House 105 Scott Stone House 106 Carla Cunningham House 107 Kelly Alexander House 108 John A. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ..................................................................................................... iii INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................ 2 ARGUMENT .............................................................................................................................. 5 I. Legislative Defendants Must Provide the Information Requested in the Second Set of Interrogatories ............................................................................................................. 5 II. In the Alternative, or if Legislative Defendants Do Not Provide The Home Addresses By March 1, the Court Should Bar Legislative Defendants From Defending the 2017 Plans on the Basis of Any Incumbency Theory................................. 7 III. The Court Should Award Fees and Expenses and Other Appropriate Relief ..................... 8 CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................................... 9 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE .................................................................................................. 11 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Cloer v. Smith , 132 N.C. App. 569, 512 S.E.2d 779 (1999)............................................................................ 7 F. E. Davis -

Who's on the Primary Ballot?

Who’s on the primary ballot? (i) Incumbent n U.S. HOUSE BOARD OF EDUCATION, CLERK OF SUPERIOR COURT BOARD OF EDUCATION, DISTRICT 1 (vote for two) DISTRICT 3 (nonpartisan)* 5TH DISTRICT Republican Democratic Democratic Brian Lee Shipwash (i) Erlie Coe (i) Chenita Barber Johnson Leigh Truelove Jenny Marshall Malishai (Shai) Woodbury BOARD OF EDUCATION, DD Adams Alex Bailand Bohannon SHERIFF DISTRICT 4 (nonpartisan)* Republican Barbara Hanes Burke Republican Terri Mosley (i) Virginia Foxx (i) Eunice Campbell David S. Grice (i) Dillon Gentry SHERIFF BOARD OF EDUCATION, Gerald K. Hege Sr. Cortland J. Meader Jr. Richie Simmons Republican DISTRICT 2 (vote for four) 13TH DISTRICT Greg Wood Jamie Goad Republican Democratic REGISTER OF DEEDS Steve C. Hiatt Lida Calvert Hayes (i) Ervin Odum Kathy Manning Republican Adam Coker Dana Caudill Jones (i) E. Vann Tate David B. Singletary (i) Michael E. Horne n N.C. SENATE Lori Goins Clark (i) David T. Rickard (i) n WATAUGA Leah H. Crowley 29TH DISTRICT n DAVIE REFERENDUM (Davidson) SHERIFF Local sales and use tax of COUNTY COMMISSIONER Republican Democratic 0.25 percent (vote for two) Eddie Gallimore Clif Kilby For Sam Watford Bobby F. Kimbrough Jr. Republican Against Tim Wooten 31ST DISTRICT John H. Ferguson (i) Republican Benita Finney COUNTY COMMISSIONER, (Forsyth, Davie, Yadkin) Charles Odell Williams DISTRICT 5 Republican Ernie G. Leyba William T. (Bill) Robert Wisecarver (i) Republican James V. Blakley Joyce Krawiec (i) Schatzman (i) Tommy Sofield Peter Antinozzi SHERIFF Allen Trivette Dan Barrett n ALLEGHANY 34TH DISTRICT Republican SHERIFF (Yadkin) COUNTY COMMISSIONER J.D. Hartman (i) Republican Mark S. -

State of North Carolina County of Wake in The

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA IN THE GENERAL COURT OF JUSTICE SUPERIOR COURT DIVISION No. 18-CVS-014001 COUNTY OF WAKE COMMON CAUSE, et al., Plaintiffs, v. Representative David R. LEWIS, in his official capacity as Senior Chairman of the House Select Committee on Redistricting, et al., Defendants. LEGISLATIVE DEFENDANTS’ AND INTERVENOR DEFENDANTS’ PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Proposed Findings of Fact ...............................................................................................................2 A. History and Development of the 2017 Plans ...........................................................2 (1) North Carolina’s Redistricting Process In 2017 ..........................................2 (2) Democratic Voters are More Concentrated Than Republican Voters .......11 a. Divided Precincts or VTDs and Divided Precincts in Current and Prior Legislative Plans ............................................................13 b. Members Elected to the General Assembly in 2010, 2016, and 2018................................................................................................14 B. Legislative Defendants’ Fact Witnesses ................................................................14 (1) William R. Gilkeson, Jr. ............................................................................14 (2) Senator Harry Brown .................................................................................17 (3) Representative John R. Bell, IV .................................................................21 -

Joint Appropriations Subcommittee for Transportation

JOINT LEGISLATIVE OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE ON HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES October 10, 2017 9:00 a.m. Legislative Office Building - Room 643 Committee Cochairs Rep. Josh Dobson I. Welcome & Opening Remarks Representative Donny Lambeth Rep. Donny Lamb eth Presiding Cochair Sen. Louis Pate II. Comments from the Secretary Mandy Cohen, MD, Secretary, Legislative Members Department of Health & Human Rep. William D. Brisson Rep. Carla D. Cunningham Services (DHHS) Rep. Nelson Dollar Rep. Beverly M. Earle III. Overview of the Committee's Purpose Lisa Wilks, Committee Staff Rep. Jean Farmer-Butterfield (Article 23A, Chapter 120) Rep. Bert Jones Rep. Chris Malone Rep. Gregory F. Murphy, MD IV. 2017 Session Resource Materials - Budget Theresa Matula, Committee Staff Rep. Donna McDowell White and Fiscal Highlights, Conference Sen. Dan Bishop Committee Report Highlights, & Sen. David L. Curtis Sen. Jim Davis Substantive Enacted HHS Legislation Sen. Valerie P. Foushee Sen. Ralph Hise V. Subcommittee Appointments Representative Donny Lambeth Sen. Joyce Krawiec Presiding Cochair Sen. Gladys A. Robinson Sen. Jeff Tarte Sen. Tommy Tucker VI. Child Welfare Updates: Sen. Mike Woodard Implementation of the Federal Susan Perry-Manning , Deputy Advisory Members Program Improvement Plan Secretary for Human Services & Rep. Gale Adcock (S.L. 2017-57, Sec. 11C.7) Michael Becketts, Assistant Sen. Tamara Barringer Secretary for Human Services, DHHS Sen. Michael V. Lee NC FAST Implementation of the Sam Gibbs, Deputy Secretary for Child Welfare Case Management Technology and Operations & System Michael Becketts, Assistant Secretary for Human Services, DHHS Planning for Implementation of Michael Becketts, Assistant Rylan's Law/Family/Child Secretary for Human Services, DHHS Protection and Accountability Act (S.L. -

State Board of Education Update New Legislative Leaders Named

January 23, 2017, Issue 660 State Board of Education Update Entering the Legal Fray: State Superintendent of Public Instruction Mark Johnson plans to join a court battle over a new law that moves power from the State Board of Education to him. Last month, the state board filed suit to block the legislation, House Bill 17, which was approved in a special legislative session in December, and a Superior Court judge enjoined a temporary restraining order to prevent the new law from taking effect Jan. 1. That restraining order will remain in effect until a three-judge panel decides on the legality of the law. Johnson was in court last week as the judges decided when to hold the next hearing in the case. An attorney representing Johnson told the judges they will make a formal notice that Johnson wants to be heard as part of the lawsuit. "The voters of North Carolina entrusted me with the tremendous responsibility to bring the changes we need for our teachers and our children," Johnson told WRAL News after the hearing. Andrew Erteschik, a lawyer representing the State Board of Education, said the board doesn't object to Johnson joining the lawsuit. Under the new law, Johnson would have more flexibility in managing the state's education budget, more power to dismiss senior-level employees, control of the Office of Charter Schools and authority to choose the leader of the new Achievement School District, which will oversee some of the lowest-performing schools in the state. The State Board of Education traditionally has had such authority. -

How to Pray, God's Way, for Your Political Leaders Who to Pray for In

How to Pray, God’s Way, Who to Pray for in North Carolina for Your Political Leaders www.pray1tim2.org www.pray1tim2.org HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES (Here are 9 suggestions based on selected scripture.) Beverly M. Earle Ken Goodman KJohn A. Fraley 1. Salvation of those who have not yet put their Verla Insko Charles Graham Sam Watford Julia C. Howard Kelly E. Hastings Gale Adcock faith in the Lord Jesus Christ Henry M. Michaux, Jr. Bert Jones John Ager Political leaders, like all people, need the forgiveness of sins and Mitchell S. Setzer Jonathan C. Jordan John R. Bradford, III the new life that comes through putting one’s faith in Jesus Marvin W. Lucas Rodney W. Moore Cecil Brockman Christ. “God our Savior . wants all men to be saved and to John M. Blust Phil Shepard Howard J. Hunter, III come to the knowledge of the truth” (1Timothy 2:3b-4). Praying Linda P. Johnson Harry Warren Larry Yarborough for the salvation of political leaders should be a top priority in a Larry M. Bell Jason Saine Lee Zachary Christian’s life (Acts 4:10-12; Romans 10:9). Becky Carney Larry G. Pittman Brian Turner 2. Divine Wisdom Tim Moore Allen McNeill Jay Adams Political leaders are regularly called upon to make very difficult Jean Farmer-Butterfield Ted Davis, Jr. Shelly Willingham decisions that affect many people. Divine wisdom is available for David R. Lewis Dean Arp Kyle Hall those who ask God for it (James 1:5). Good decisions will seldom John Sauls Jeffrey Elmore Scott Stone be made without God’s wisdom (Psalm 111:10). -

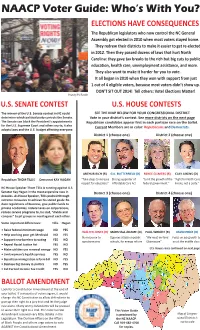

NAACP Voter Guide: Who’S with You?

NAACP Voter Guide: Who’s With You? ELECTIONS HAVE CONSEQUENCES The Republican legislators who now control the NC General Assembly got elected in 2010 when most voters stayed home. They redrew their districts to make it easier to get re-elected in 2012. Then they passed dozens of laws that hurt North Carolina: they gave tax breaks to the rich but big cuts to public education, health care, unemployment assistance, and more. They also want to make it harder for you to vote. It all began in 2010 when they won with support from just 1 out of 4 eligible voters, because most voters didn’t show up. DON’T SIT OUT 2014! Tell others: Vote! Elections Matter! Photo by Phil Fonville U.S. SENATE CONTEST U.S. HOUSE CONTESTS The winner of the U.S. Senate contest in NC could SEE THE MAP BELOW FOR YOUR CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT determine which political party controls the Senate. Vote in your district’s contest. See more districts on the next page The Senate can block the President’s appointments Republican candidates appear first in each partisan race on the ballot. for the U.S. Supreme Court and other courts; it also Current Members are in color: Republicans and Democrats. adopts laws and the U.S. budget affecting everyone. District 1 (choose one) District 2 (choose one) ARTHUR RICH (R) G.K. BUTTERFIELD (D) RENEE ELLMERS (R) CLAY AIKENS (D) Republican THOM TILLIS Democrat KAY HAGAN “Take steps to increase Strong supporter of “Limit the growth of the “Fight for North Caro- respect for educators” Affordable Care Act federal government.” linians, not a party.” NC House Speaker Thom Tillis is running against U.S. -

Member Address Phone Legislative Assistants District Party Sen. John M

NORTH CAROLINA GENERAL ASSEMBLY 10/29/2018 2017 SESSION 31st Edition SENATE MEMBERS AND LEGISLATIVE ASSISTANTS Member Address Phone Legislative Assistants District Party Sen. John M. Alexander, Jr. 625 LOB (919) 733-5850 Jessica Daigler-Walls 15 R Sen. Deanna Ballard 521 LOB (919) 733-5742 William Verbiest 45 R Sen. Chad Barefoot 406 LOB (919) 715-3036 Holden McLemore 18 R Sen. Dan Barrett 310 LOB (919) 715-0690 Judy Edwards 34 R Sen. Tamara Barringer 629 LOB (919) 733-5653 Devon Karst 17 R Sen. Phil Berger 2007 LB (919) 733-5708 Peggy Halifax, Wanda Shivers 26 R Sen. Dan Bishop 2108 LB (919) 733-5655 John Wynne 39 R Sen. Dan Blue 1129 LB (919) 733-5752 Bonnie McNeil 14 D Sen. Danny Earl Britt, Jr. 2117 LB (919) 733-5651 Cindy Davis 13 R Sen. Harry Brown 300-B LOB (919) 715-3034 Lorie Byrd 6 R Sen. Jay J. Chaudhuri 1121 LB (919) 715-6400 Antoine Marshall 16 D Sen. Ben Clark 1117 LB (919) 733-9349 Erhonda Farmer 21 D Sen. Bill Cook 1026 LB (919) 715-8293 Jordan Hennessy 1 R Sen. Warren Daniel 627 LOB (919) 715-7823 Andy Perrigo 46 R Sen. Don Davis 519 LOB (919) 715-8363 Blinda Edwards 5 D Sen. Jim Davis 621 LOB (919) 733-5875 Johnny Bravo 50 R Sen. Cathy Dunn 2113 LB (919) 733-5665 Judy Chriscoe 33 R Sen. Chuck Edwards 2115 LB (919) 733-5745 Danielle Plourd 48 R Sen. Milton F. “Toby” Fitch, Jr. 206-C LOB (919) 733-5878 Jacqueta Rascoe 4 D Sen. -

Candidate List Grouped by Contest Alamance Board of Elections Alamance

ALAMANCE BOARD OF ELECTIONS CANDIDATE LIST GROUPED BY CONTEST CRITERIA: Election: 11/03/2020, Show Contest w/o Candidate: Y, County: ALL COUNTIES, Data Source: FULL COUNTY VIEW CANDIDATE NAME NAME ON BALLOT PARTY FILING DATE ADDRESS ALAMANCE US PRESIDENT TRUMP, DONALD J Donald J. Trump REP 08/14/2020 BIDEN, JOSEPH R Joseph R. Biden DEM 08/14/2020 BLANKENSHIP, DON Don Blankenship CST 08/14/2020 HAWKINS, HOWIE Howie Hawkins GRE 08/14/2020 JORGENSEN, JO Jo Jorgensen LIB 08/14/2020 US SENATE TILLIS, THOMAS ROLAND Thom Tillis REP 12/09/2019 P. O. BOX 97396 RALEIGH, NC 27624 BRAY, SHANNON WILSON Shannon W. Bray LIB 12/11/2019 215 MYSTIC PINE PL APEX, NC 27539 CUNNINGHAM, JAMES CALVIN III Cal Cunningham DEM 12/03/2019 PO BOX 309 RALEIGH, NC 27602 HAYES, KEVIN EUGENE Kevin E. Hayes CST 12/19/2019 416 S WEST CENTER ST FAISON, NC 28341 US HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES DISTRICT 13 BUDD, THEODORE PAUL Ted Budd REP 12/03/2019 PO BOX 97127 RALEIGH, NC 27624 HUFFMAN, JEFFREY SCOTT Scott Huffman DEM 12/20/2019 4311 SCHOOL HOUSE COMMONS HARRISBURG, NC 28075 NC GOVERNOR PISANO, ALBERT LAWRENCE Al Pisano CST 12/19/2019 7209 E.W.T. HARRIS BLVD. STE. J 119 CHARLOTTE, NC 28227 COOPER, ROY ASBERRY III Roy Cooper DEM 12/05/2019 434 FAYETTEVILLE ST RALEIGH, NC 27601 STE 2020 DIFIORE, STEVEN JOSEPH II Steven J. DiFiore LIB 12/20/2019 6817 FISHERS FARM LN UNIT C1 CHARLOTTE, NC 28277 FOREST, DANIEL JAMES Dan Forest REP 12/04/2019 PO BOX 471845 CHARLOTTE, NC 28247 CONT_CAND_rpt_3.rpt Page 1 of 545 Sep 02, 2020 3:52 pm ALAMANCE BOARD OF ELECTIONS CANDIDATE LIST GROUPED BY CONTEST CANDIDATE NAME NAME ON BALLOT PARTY FILING DATE ADDRESS ALAMANCE NC LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR ROBINSON, MARK KEITH Mark Robinson REP 12/02/2019 P.O. -

General Assembly of North Carolina

General Assembly of North Carolina SENIOR CHAIRMAN House Select Committee on North Carolina REP. TED DAVIS, JR. COMMITTEE STAFF JEFF HUDSON COMMITTEE CHAIRMEN River Quality COMMITTEE COUNSEL REP. HOLLY GRANGE 545 LEGISLATIVE OFFICE BUILDING REP. FRANK ILER State Legislative Building 300 NORTH SALISBURY STREET _______________________________ RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA 27603 Raleigh, North Carolina (919) 733-2578 COMMITTEE MEMBERS _________________________________ REP. WILLIAM BRISSON REP. JIMMY DIXON JENNIFER McGINNIS REP. ELMER FLOYD COMMITTEE COUNSEL REP. KYLE HALL REP. PRICEY HARRISON CHRIS SAUNDERS REP. PAT MCELRAFT COMMITTEE COUNSEL REP. CHUCK MCGRADY REP. BOB MULLER MARIAH MATHESON REP. BOB STEINBURG COMMITTEE ASSISTANT REP. SCOTT STONE REP. LARRY YARBOROUGH ANDREW BOWERS COMMITTEE CLERK AGENDA 9:30 a.m. Thursday, April 26, 2018 Room 643 Legislative Office Building Raleigh, North Carolina 1. Call to order Representative Ted Davis, presiding 2. Introductory remarks by Cochairs Representative Ted Davis Representative Holly Grange Representative Frank Iler 3. Approval of minutes September 28, 2017 Minutes October 26, 2017 Minutes November 30, 2017 Minutes January 4, 2018 Minutes 4. Department of Environmental Quality update on response to emerging compounds (1 hour) Sheila Holman, Assistant Secretary for Environment Department of Environmental Quality 5. Final report on implementation of Section 20(a)(1) of S.L. 2017-209 (House Bill 56) (GenX Response Measures) (45 minutes) Jim Flechtner, Executive Director Cape Fear Public Utility Authority 6. Final report on implementation of Section 20(a)(2) of S.L. 2017-209 (House Bill 56) (GenX Response Measures) (45 minutes) Dr. Ralph Mead, Professor, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry University of North Carolina Wilmington Mark Lanier, Assistant to the Chancellor University of North Carolina Wilmington 7. -

Ted Davis Jr., a Descendent of One of New Hanover's Wealthiest Families

Rep. Ted Davis, Jr. (R-New Hanover) House District 19 “All I know is that we’re doing something” –Rep. Ted Davis, in response to the Senate’s unwillingness to take up his GenX bill. (WRAL, 1/10/18) Ted Davis Jr., a descendent of one of New Hanover’s wealthiest families, followed an uneventful legal career with an unremarkable tenure as county commissioner. Davis switched affiliation to Republican for political expedi ence in order to run for public office. He was elected to the legislature in 2012 and has largely been a cog in the Raleigh political machine. As such, he failed to deliver anything of note for the Wilmington area, like the return of meaningful film incentives. Davis’ s time in the state House is probably most exemplified by his tenure as Chair of the House Select Committee on River Quality set up to “res pond” to the GenX crisis. In a role meant to give Davis a chance to shine , he has so far doled out taxpayer money to political cronies of Republican leadership and allowed a trade association lobbyist for Chemours , the company responsible for dumping GenX in our drinking water, to write three budget provisions that let the polluter off the hook. Rep. Ted Davis, Jr. Meanwhile Cape Fear Public Utility Authority customers are seeing their bills go up to pay for GenX cleanup and taxpayers are stuck with the bill for more “study” of the problem. Davis ’s inept handling of GenX is just the latest example of his failure to provide meaningful service to the people of his district as he plays follow- the- leader in Raleigh.