The Ordeal of Mr. Pepys's Clerk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

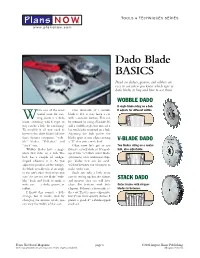

Dado Blade BASICS Dead-On Dadoes, Grooves, and Rabbets Are Easy to Cut When You Know Which Type of Dado Blades to Buy and How to Use Them

TOOLS & TECHNIQUES SERIES Plans NOW® www.plansnow.com Dado Blade BASICS Dead-on dadoes, grooves, and rabbets are easy to cut when you know which type of dado blades to buy and how to use them. WOBBLE DADO A single blade riding on a hub. hile one of the most One downside of a wobble It adjusts for different widths. useful tools for cut- blade is that it may leave a cut Wting joints is a dado with a concave bottom. This can blade, selecting which type to be reduced by using a V-blade. It’s buy can be a little bit confusing. still a wobble-style, but instead it To simplify it, all you need to has two blades mounted on a hub. know is that dado blades fall into Adjusting the hub pushes the three distinct categories: “wob- blades apart at one edge, creating V-BLADE DADO ble” blades, “V-blades,” and a “V” that cuts a wide kerf. “stack” sets. Okay, now let’s get to my Two blades riding on a center Wobble blades have a single favorite:a stack dado set.It’s made hub, also adjustable. 1 blade that rides on a hub. The up of two /8"-thick outer blades hub has a couple of wedge- (trimmers) with additional chip- shaped adjusters in it. As you per blades that can be sand- adjust the position of the wedges, wiched between the trimmers to the blade actually tilts at an angle make wider cuts. to the saw’s arbor.And, when you Stack sets take a little more turn the saw on, the blade “wob- care in setting up, but the dadoes STACK DADO bles” back and forth to make a and grooves they cut will have wide cut — a dado, groove, or clean, flat bottoms with little Outer blades with chipper rabbet. -

POLITICS, SOCIETY and CIVIL WAR in WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History Series editors ANTHONY FLETCHER Professor of History, University of Durham JOHN GUY Reader in British History, University of Bristol and JOHN MORRILL Lecturer in History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow and Tutor of Selwyn College This is a new series of monographs and studies covering many aspects of the history of the British Isles between the late fifteenth century and the early eighteenth century. It will include the work of established scholars and pioneering work by a new generation of scholars. It will include both reviews and revisions of major topics and books which open up new historical terrain or which reveal startling new perspectives on familiar subjects. It is envisaged that all the volumes will set detailed research into broader perspectives and the books are intended for the use of students as well as of their teachers. Titles in the series The Common Peace: Participation and the Criminal Law in Seventeenth-Century England CYNTHIA B. HERRUP Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, 1620—1660 ANN HUGHES London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration to the Exclusion Crisis TIM HARRIS Criticism and Compliment: The Politics of Literature in the Reign of Charles I KEVIN SHARPE Central Government and the Localities: Hampshire 1649-1689 ANDREW COLEBY POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, i620-1660 ANN HUGHES Lecturer in History, University of Manchester The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry VIII in 1534. -

The Sun King and the Merry Monarch

The Sun King and the Merry 1678 Monarch Explores the religious backdrop to one of the largest threats to England's throne - the Popish Plot. Aggravated by the murder of the magistrate Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey, the Plot reflected religious beliefs and insecurities at the By Calum time. Sir Godfrey was my ancestor (of some 11 generations). A visit to his Johnson grave in Westminster Abbey in 2014 inspired me to explore his role in this religious turmoil which hit hard in 17th Century England... The Clergyman and the King of England Leaving for his morning stroll on the 13th of August 1678, Charles II, King of England and Defender of the Faith heard for the first time of a plot to kill him. This was far from unusual. Indeed, just months earlier, a woman in Newcastle had been subjected to a large investigation after stating, "the King deserves the curse of all good and faithful wives for his bad example”. And yet, when Mr Kirkby (his lab assistant) brought Dr Israel Tonge to him at 8 o’clock that evening, the king listened impatiently before handing the matter over to his first minister…. The Religious Pendulum: Change of Faith in England To truly examine the tumult about to hit England in the 17th Century, it is important that we look first at the Religious scene in Europe some 150 years earlier. In the previous century the Reformation began and Protestantism gathered momentum, fuelled by a desire to reduce the exuberance of the Church in Rome with its elaborate sculptures, paintings and stained-glass windows. -

Restoration and Renewal of the Palace of Westminster

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07898, 3 December 2018 Restoration and Renewal By Richard Kelly of the Palace of Westminster Contents: 1. Overview of the Restoration and Renewal Programme 2. Pre-feasibility study (2012) 3. Independent Options Appraisal (2014) 4. Joint Committee review of the Options (2016) 5. Debate on the Joint Committee’s report 6. Draft Parliamentary Buildings (Restoration and Renewal) Bill 7. Earlier debate on and other proposals for R&R 8. Reviewing the Joint Committee’s proposals 9. Opportunities arising from R&R 10. Restorations of other public buildings www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Restoration and Renewal of the Palace of Westminster Contents Summary 4 Legislating for Restoration and Renewal 4 Recommendations on Restoration and Renewal to the two Houses 4 Debating R&R 5 Further inquiries 5 How were the options developed? 5 1. Overview of the Restoration and Renewal Programme 7 1.1 Refurbishment to date 8 1.2 Timeline of the R&R Programme 8 1.3 The scale of the problem 11 Costs of delay 13 1.4 Decisions already taken 13 R&R Programme Spending 16 1.5 Next steps for the Restoration and Renewal Programme 17 Joint Committee’s timeline, September 2016 17 Timeline, January 2018 18 Legislation timetable 19 2. Pre-feasibility study (2012) 20 3. Independent Options Appraisal (2014) 22 3.1 Outcome of the appraisal 22 4. Joint Committee review of the Options (2016) 26 4.1 A full decant 26 4.2 Temporary accommodation 27 4.3 Governance arrangements 28 4.4 Decisions following the Joint Committee report 29 5. -

PLEASE NOTE This Is a Draft Paper Only and Should Not Be Cited Without

PLEASE NOTE This is a draft paper only and should not be cited without the author’s express permission THE SHORT-TERM IMPACT OF THE >GLORIOUS REVOLUTION= ON THE ENGLISH JUDICIAL SYSTEM On February 14, 1689, The day after William and Mary were recognized by the Convention Parliament as King and Queen, the first members of their Privy Council were sworn in. And, during the following two to three weeks, all of the various high offices in the government and the royal household were filled. Most of the politically powerful posts went either to tories or to moderates. The tory Earl of Danby was made Lord President of the Council and another tory, the Earl of Nottingham was made Secretary of State for the Southern Department. The office of Lord Privy Seal was given to the Atrimming@ Marquess of Halifax, whom dedicated whigs had still not forgiven for his part in bringing about the disastrous defeat of the exclusion bill in the Lords= house eight years earlier. Charles Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, who was named Principal Secretary of State, can really only be described as tilting towards the whigs at this time. But, at the Admiralty and the Treasury, both of which were put into commission, in each case a whig stalwart was named as the first commissioner--Lord Mordaunt and Arthur Herbert respectivelyBand also in each case a number of other leading whigs were named to the commission as well.i Whig lawyers, on the whole, did rather better than their lay fellow-partisans. Devonshire lawyer and Inner Temple Bencher Henry Pollexfen was immediately appointed Attorney- General, and his cousin, Middle Templar George Treby, Solicitor General. -

Arcadia Disjointed: Confrontations with Texts, Polemical, Utopian, and Picaresque

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1991 Arcadia Disjointed: Confrontations With Texts, Polemical, Utopian, and Picaresque. Deborah Ann Jacobs Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Jacobs, Deborah Ann, "Arcadia Disjointed: Confrontations With Texts, Polemical, Utopian, and Picaresque." (1991). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5126. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5126 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Lyings in State

Lyings in state Standard Note: SN/PC/1735 Last updated: 12 April 2002 Author: Chris Pond Parliament and Constitution Centre On Friday 5 April 2002, the coffin of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother was carried in a ceremonial procession to Westminster Hall, where it lay in state from the Friday afternoon until 6 a.m. on Tuesday 9 April. This Standard Note gives a history of lying in state from antiquity, and looks at occasions where people have lain in state in the last 200 years. Contents A. History of lying in state 2 B. Lyings in state in Westminster Hall 2 1. Gladstone 3 2. King Edward VII 3 3. Queen Alexandra 5 4. Victims of the R101 Airship Disaster, 1930 5 5. King George V 6 6. King George VI 6 7. Queen Mary 6 8. Sir Winston Churchill 7 9. Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother 7 C. The pattern 8 Annex 1: Lyings in state in Westminster Hall – Summary 9 Standard Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of Parliament and their personal staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of these papers with Members and their staff but cannot advise others. A. History of lying in state The concept of lying in state has been known from antiquity. In England in historical times, dead bodies of people of all classes “lay” – that is, were prepared and dressed (or “laid out”) and, placed in the open coffin, would lie in a downstairs room of the family house for two or three days whilst the burial was arranged.1 Friends and relations of the deceased could then visit to pay their respects. -

Chapter VIII Witchcraft As Ma/Efice: Witchcraft Case Studies, the Third Phase of the Welsh Antidote to Witchcraft

251. Chapter VIII Witchcraft as Ma/efice: Witchcraft Case Studies, The Third Phase of The Welsh Antidote to Witchcraft. Witchcraft as rna/efice cases were concerned specifically with the practice of witchcraft, cases in which a woman was brought to court charged with being a witch, accused of practising rna/efice or premeditated harm. The woman was not bringing a slander case against another. She herself was being brought to court by others who were accusing her of being a witch. Witchcraft as rna/efice cases in early modem Wales were completely different from those witchcraft as words cases lodged in the Courts of Great Sessions, even though they were often in the same county, at a similar time and heard before the same justices of the peace. The main purpose of this chapter is to present case studies of witchcraft as ma/efice trials from the various court circuits in Wales. Witchcraft as rna/efice cases in Wales reflect the general type of early modern witchcraft cases found in other areas of Britain, Europe and America, those with which witchcraft historiography is largely concerned. The few Welsh cases are the only cases where a woman was being accused of witchcraft practices. Given the profound belief system surrounding witches and witchcraft in early modern Wales, the minute number of these cases raises some interesting historical questions about attitudes to witches and ways of dealing with witchcraft. The records of the Courts of Great Sessions1 for Wales contain very few witchcraft as rna/efice cases, sometimes only one per county. The actual number, however, does not detract from the importance of these cases in providing a greater understanding of witchcraft typology for early modern Wales. -

Dado & Accessories

20-73 pages 8-28-06 8/30/06 11:21 AM Page 63 Dado Sets & Saw Blade Accessories Dado Sets 63 Whether you’re a skilled professional or a weekend hobbiest, Freud has a dado for you. The SD608, Freud’s Dial-A-Width Dado, has a patented dial system for easy and precise adjustments while offering extremely accurate cuts. The SD300 Series adds a level of safety not found in other manufacturers’ dadoes, while the SD200 Series provides the quality of cuts you expect from Freud, at an attractive price. 20-73 pages 8-28-06 8/30/06 11:21 AM Page 64 Dial-A-Width Stacked Dado Sets NOT A 1 Loosen SD600 WOBBLE Series DADO! 2 Turn The Dial 3 Tighten Features TiCo™ High Dado Cutter Heads Density Carbide Crosscutting Blend For Maximum Performance Chip Free Dadoes In Veneered Plywoods and Laminates The Dial-A-Width Dado set performs like a stacked dado, but Recommended Use & Cut Quality we have replaced the shims with a patented dial system and HARDWOOD: with our exclusive Dial hub, ensures accurate adjustments. SOFTWOOD: Each “click” of the dial adjusts the blade by .004". The Dial- A-Width dado set is easy to use, and very precise. For the CHIP BOARD: serious woodworker, there’s nothing better. PLYWOOD: • Adjusts in .004" increments. 64 LAMINATE: • Maximum 29/32" cut width. NON-FERROUS: • Adjusts easily to right or left operating machines. • Set includes 2 outside blades, 5 chippers, wrench and Application CUT QUALITY: carrying case. (Not recommended for ferrous metals or masonry) • Does not need shims. -

Happy Birthday, Monsieur Jaques! Bon Anniversaire, Monsieur Jaques ! Foreword Paul Hille, Vienna, Feb

2015 150 Happy birthday, Monsieur Jaques! Bon anniversaire, Monsieur Jaques ! Foreword Paul Hille, Vienna, Feb. 2016 2015 was a great year for the international field’s major event of scientific exchange and Eurhythmics community due to Émile Jaques-Dal- acknowledgment of the crucial impulses by croze’s 150th birthday. This volume of Le Rythme the founder of Eurhythmics, including his documents three mayor events. In March: method but also his philosophy and Wel- q The Remscheid Conference: Émile Jaques- tanschauung. Dalcroze 150 – Bonne anniversaire! Interna- All the three events and with them the articles tional Eurhythmics Festival with a special by authors from Germany, Australia, Austria, the artistic outcome by the foundation of the USA, Canada, Korea —for the first time! — and Remscheid Open Arts Rhythmics Reactor/ the UK show that our community is on its way to ROARR. q a more specific scientific discourse. Eckart In July: Altenmüller explains the multisensory-mo- q The Geneva Congrès International Jaques- tor integration, audiation and embodiment Dalcroze, which concerned the interactions of Eurhythmics. between pedagogy, art and science and their q expand historical research on the first and influence on learning music through music later generations of Dalcroze teachers. Ka- today and in future times. rin Greenhead describes personalities and q The 2nd International Conference of Dalcroze situations, which influenced Émile Jaques- Studies (ICDS) in Vienna. Thanks to John Dalcroze’s life and investigates why and how Habron, this conference has become our he created his method. She also gives an About Le Rythme est édité par la FIER (Fédération Internationale des Enseignants de Rythmique) Siège social : 44, Terrassière, CH-1207 Genève www.fier.com | [email protected] The views expressed in Le Rythme do not necessarily represent those of FIER. -

The Jesuits and the Popish Plot

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1950 The Jesuits and the Popish Plot Robert Joseph Murphy Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Murphy, Robert Joseph, "The Jesuits and the Popish Plot" (1950). Master's Theses. 1177. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/1177 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1950 Robert Joseph Murphy THE JESUITS AND THE POPISH PLOT BY ROBERT J. MURPHY. S.d. A THESIS SUBMITTED II PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE or MAStER OF ARTS IN LOYOLA UNIVERSITY JULY 1950 VI't A AUCTORIS Robert Joseph Murphy was born in Chicago, Illinois, April 15. 1923. He received his elementary education at St. Mel School. Ohicago, Ill.,. graduating in June, 1937 • Ho attended St. Mel High School tor one year and St. Ignatius High School. Chicago, Ill., grQduat1ng in June. 1941. In August, 1941, he entered the Jesuit Novitiate of the Sacred Heart, Millord, Ohio, remaining there until August 1945. 'that same month he entered West Baden College, West Baden Springs, Indiana, and transtered his studies in the Department of History to Loyola University, Ohicago, Ill. He received hi. Bachelor ot Arts degree in June, 1946, and began his graduate studies at Loyola in September 1946. -

Journal of British Studies Volume 55, No. 4 (October 2016) Glickman

Journal of British Studies Volume 55, no. 4 (October 2016) Glickman Catholic Interests and the Politics of English Overseas Expansion 16601689 Gabriel Glickman Journal of British Studies 55:4 (October 2016): - © 2016 by The North American Conference on British Studies All Rights Reserved Journal of British Studies Volume 55, no. 4 (October 2016) Glickman Catholic Interests and the Politics of English Overseas Expansion 16601689 The link between English Protestantism and Early Modern English imperialism was once self-evident—to modern scholars as to many contemporary authors. The New World figured as a holy land for Calvinists and evangelicals, from Richard Hakluyt to Oliver Cromwell. Colonial schemes from the Providence Island expedition of 1631 to the 1655 Western Design were proclaimed as strikes upon the Roman-Iberian Babylon in its garrisoned treasure- house.1 Until well into the eighteenth century, overseas conquests were retailed as the providential tokens of an elect nation—an expanding domain that considered itself, in David Armitage’s words, to be “Protestant, commercial, maritime and free.”2 This ideology formed Gabriel Glickman is a Lecturer in History at Cambridge University. He would like to thank Mark Knights and Mark Goldie for their comments on an earlier draft of this article. He is also grateful for the thoughts of the reviewers selected by the Journal of British Studies, and for the suggestions of the editor, Holger Hoock. 1 K. O. Kupperman, “Errand to the Indies: Puritan Colonization from Providence Island through the Western Design,” William and Mary Quarterly (henceforth W&MQ) 45, no.1 (January 1988): 7099. 2 David Armitage, Ideological Origins of the British Empire (Cambridge, 2000), 61-3, 173; Carla Gardina Pestana, Protestant Empire: Religion and the Making of the British Atlantic 2 it has been suggested, when its champions defined the purpose and politics of the English overseas empire against a host of cultural and ethnic “Others”.