Leeds House of Recovery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leeds Pottery

Leeds Art Library Research Guide Leeds Pottery Our Art Research Guides list some of the most unique and interesting items at Leeds Central Library, including items from our Special Collections, reference materials and books available for loan. Other items are listed in our online catalogues. Call: 0113 378 7017 Email: [email protected] Visit: www.leeds.gov.uk/libraries leedslibraries leedslibraries Pottery in Leeds - a brief introduction Leeds has a long association with pottery production. The 18th and 19th centuries are often regarded as the creative zenith of the industry, with potteries producing many superb quality pieces to rival the country’s finest. The foremost manufacturer in this period was the Leeds Pottery Company, established around 1770 in Hunslet. The company are best known for their creamware made from Cornish clay and given a translucent glaze. Although other potteries in the country made creamware, the Leeds product was of such a high quality that all creamware became popularly known as ‘Leedsware’. The company’s other products included blackware and drabware. The Leeds Pottery was perhaps the largest pottery in Yorkshire. In the early 1800s it used over 9000 tonnes of coal a year and exported to places such as Russia and Brazil. Business suffered in the later 1800s due to increased competition and the company closed in 1881. Production was restarted in 1888 by a ‘revivalist’ company which used old Leeds Pottery designs and labelled their products ‘Leeds Pottery’. The revivalist company closed in 1957. Another key manufacturer was Burmantofts Pottery, established around 1845 in the Burmantofts district of Leeds. -

Properties for Customers of the Leeds Homes Register

Welcome to our weekly list of available properties for customers of the Leeds Homes Register. Bidding finishes Monday at 11.59pm. For further information on the properties listed below, how to bid and how they are let please check our website www.leedshomes.org.uk or telephone 0113 222 4413. Please have your application number and CBL references to hand. Alternatively, you can call into your local One Stop Centre or Community Hub for assistance. Date of Registration (DOR) : Homes advertised as date of registration (DOR) will be let to the bidder with the earliest date of registration and a local c onnection to the Ward area. Successful bidders will need to provide proof of local connection within 3 days of it being requested. Maps of Ward areas can be found at www.leeds.gov.uk/wardmaps Aug 11 2021 to Aug 16 2021 Ref Landlord Address Area Beds Type Sheltered Adapted Rent Description DOR Silkstone House, Fox Lane, Allerton Single or a couple 11029 Home Group Bywater, WF10 2FP Kippax and Methley 1 Flat No No 411.11 No BAILEYS HILL, SEACROFT, LEEDS, Single/couple 11041 The Guinness LS14 6PS Killingbeck and Seacroft 1 Flat No No 76.58 No CLYDE COURT, ARMLEY, LEEDS, LS12 Single/couple 11073 Leeds City Council 1XN Armley 1 Bedsit No No 63.80 No MOUNT PLEASANT, KIPPAX, LEEDS, Single 55+ 11063 Leeds City Council LS25 7AR Kippax and Methley 1 Bedsit No No 83.60 No SAXON GROVE, MOORTOWN, LEEDS, Single/couple 11059 Leeds City Council LS17 5DZ Alwoodley 1 Flat No No 68.60 No FAIRFIELD CLOSE, BRAMLEY, LEEDS, Single/couple 25+ 11047 Leeds City Council -

Leeds Bradford

Harrogate Road Yeadon Leeds West Yorkshire LS19 7XS INDUSTRIAL UNITS TO LET SAT NAV: LS19 7XS Unit 9 Unit 1B Knaresborough A59 Harrogate Produced by www.impressiondp.co.uk A1(M) Skipton Wetherby A65 A61 Keighley A660 A650 A658 LEEDS BRADFORD M621 M62 M62 M1 Old Bramhope Bramhope A658 Guiseley CONTACT Yeadon A65 Cookridge A660 0113 245 6000 Rawdon Rob Oliver Andrew Gent A658 [email protected] [email protected] A65 Iain McPhail Nick Prescott Horsforth Apperley [email protected] [email protected] Bridge A6120 Weetwood IMPORTANT NOTICE RELATING TO THE MISREPRESENTATION ACT 1967 AND THE PROPERTY MISDESCRIPTION ACT 1991. A65 GVA Grimley and Gent Visick on their behalf and for the sellers or lessors of this property whose agents they are, give notice that: (i) The Particulars are set out as a general outline only for the guidance of intending purchasers or lessees, and do not constitute, nor constitute part of, an offer or contract; (ii) All descriptions, dimensions, references to condition and necessary permissions for use and occupation, and other details are given in good faith and are believed to be correct, but any intending purchasers or tenants should not rely on them as statements or representations of fact, but must satisfy themselves by inspection or otherwise as to the correctness of each of them; (iii) No person employed by GVA Grimley and Gent Visick has any authority to make or give any representation or warranty in relation to this property. Unless otherwise stated prices and rents quoted are exclusive of VAT. -

Properties for Customers of the Leeds Homes Register

Welcome to our weekly list of available properties for customers of the Leeds Homes Register. Bidding finishes Monday at 11.59pm. For further information on the properties listed below, how to bid and how they are let please check our website www.leedshomes.org.uk or telephone 0113 222 4413. Please have your application number and CBL references to hand. Alternatively, you can call into your local One Stop Centre or Community Hub for assistance. Date of Registration (DOR) : Homes advertised as date of registration (DOR) will be let to the bidder with the earliest date of registration and a local c onnection to the Ward area. Successful bidders will need to provide proof of local connection within 3 days of it being requested. Maps of Ward areas can be found at www.leeds.gov.uk/wardmaps Aug 4 2021 to Aug 9 2021 Ref Landlord Address Area Beds Type Sheltered Adapted Rent Description DOR Beech View , Aberford , Leeds, LS25 Single/couple 10984 Leeds City Council 3BW Harewood 1 Bungalow No No 88.49 No LANDSEER ROAD, BRAMLEY, LEEDS, Single person or couple 10987 Leeds City Council LS13 2QP Bramley and Stanningley 1 Flat No No 66.26 No COTTINGLEY TOWERS, Cottingley Single person or couple 10989 Leeds City Council Drive , Beeston , Leeds , LS11 0JH Beeston and Holbeck 1 Flat No No 69.44 No KINGSWAY, DRIGHLINGTON, Single person or couple 10993 Leeds City Council BRADFORD, LEEDS, BD11 1ET Morley North 1 Flat No No 66.30 No NEWHALL GARDENS, MIDDLETON, Single/couple 11000 Leeds City Council LEEDS, LS10 3TF Middleton Park 1 Flat No No 63.52 No NORTH -

LEEDS DIRECTORY, Hogg 1\[R John, 52 Camp Road Hollings John, Woollen Manufacturer and Hogg Thos

82 LEEDS DIRECTORY, Hogg 1\[r John, 52 Camp road Hollings John, woollen manufacturer and Hogg Thos. bookkeeper, 179 Dewsbury rd merchant, 10 York place; h Ilorsforth Hoggard Alfred, builder, 16 Booth street Hollings Thos. shopkeeper, Hunslet carr Hoggard & Co. machine mfTS. Robert street Hollings William, victualler, Old Nag's Hoggard George, tailor, 41 1\Iarshall street Head, 56 Kirkgate Hoggard John, beerhouse, 42 Marshall st Hollingworth Isaac, gutta percba manufac- Holden George, butcher, 48 Fleet street ; turer, Dewsbury road; h 5 Pemberton st h 1 Brunswick row Hollingworth Sarah, shopr. 18 St. 1\Iark s\ Holden Richard, shoemaker, 13 Elland row Hollingworth Thos. shopr. Granville ter Holder John, milk dealer, \Vright street Hollingworth Thos. painter, Lisbon street; Holder Thomas, undertaker, 31 Bank street h 7 Burley road Holford Mr George, Chapelt01cn Holl:lngworth Wm.travg.tea dlr.71 Ellerby lp. Holdforth Jas. & Son, silk spinners, Bank Hollins l\Iarmaduke, potato dealer, Vicax's Low Mills, Mill street, & Cookridge ~.fills croft; h Union street Holdforth Waiter (Jas. & Son); h .Arthington llollins Thomas, tripe dresser, Bunt street Holdsworth Mr Henry, 21 Grove terrace Holloway Richard, eating and beerhouse, Holdsworth James, glass and china dealer, 192 W ellipgton street 61 \Voodhousc lano Hollway Thomas Saunders, manager, lO Holdsworth James, beerhs. 26 Dewsbury rd Elmwood grove Holdsworth ~fr John, Eastfield, Chapeltou;n Holmes Abm. hairdresser, 20 Grey stree~ Holdsworth John, stone and marble mason, Holmes Ann, grocer, Butterley street 78 Castle street Holmes Chas. carver & gilder, 8 Albion st Holdsworth John, mason, Francis street Holmes Charles, shopkeeper, 7 Carlton st Holdsworth .T ohn, cashier, 49 Holdforth st Holmes David, auctioneer and furniture Holdsworth Jph. -

Health Profile Overview for Burmantofts and Richmond Hill Ward

Burmantofts and Richmond Hill Ward Health profile overview for Burmantofts and Richmond Hill ward Population: 30,290 Burmantofts and Richmond Hill ward has a GP Comparison of ward Leeds age structures July 2018. registered population of 30,290 making it the fifth Mid range Most deprived 5th Least deprived 5th largest ward in Leeds with the majority of the ward population living in the most deprived fifth of Leeds. 100-104 Males: 15,829 Females: 14,458 In Leeds terms the ward is ranked second by 90-94 deprivation score . 80-84 70-74 The age profile of this ward is similar to Leeds, but 60-64 with fewer elderly and many more children. 50-54 This profile presents a high level summary of health 40-44 related data sets for the Burmantofts and Richmond 30-34 Hill ward. 20-24 10-14 All wards are ranked to display variation across Leeds 0-4 and this one is outlined in red. 6% 3% 0% 3% 6% Leeds overall is shown as a horizontal black line, Deprived Deprivation in this ward Leeds** (or the most deprived fifth**) is an orange dashed Proportions of this population within each deprivation 'quintile' horizontal. The MSOAs that make up this ward are overlaid or fifth of Leeds* (Leeds therefore has equal proportions of 20%) as red circles and often range widely. July 2018. 81% Most of the data is provided for the new wards as redesigned in 2018, however 'obese smokers', and 'child obesity' are for the previous wards and the best match is 19% used in these cases. -

Please Could You Provide the Following Information

Please could you provide the following information: The address, crime date, offence type, crime reference number and theft value (if logged/applicable) of each crime reported between December 1 2016 and December 1 2018 that include any of the search terms listed below and any of the criminal offence types listed below. Search terms: • Cash and carry • Cash & carry • Depot • Wholesale • Booker • Bestway • Parfetts • Dhamecha • Blakemore • Filshill *Criminal offence types requested: • Burglary • Theft (including from a vehicle) • Robbery (including armed) • Violence against the person Please see the attached document. West Yorkshire Police can confirm the information requested is held, however we are unable to provide the crime reference numbers, this information is exempt by virtue of section 40(2) Personal Information. Please see Appendix A, for the full legislative explanation as to why West Yorkshire Police are unable to provide the information. Appendix A The Freedom of Information Act 2000 creates a statutory right of access to information held by public authorities. A public authority in receipt of a request must, if permitted, state under Section 1(a) of the Act, whether it holds the requested information and, if held, then communicate that information to the applicant under Section 1(b) of the Act. The right of access to information is not without exception and is subject to a number of exemptions which are designed to enable public authorities, to withhold information that is unsuitable for release. Importantly the Act is designed to place information into the public domain. Information is granted to one person under the Act, it is then considered public information and must be communicated to any individual, should a request be received. -

Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields in the Cookridge Area of Leeds, England

Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields in the Cookridge Area of Leeds, England S Y Ely, K Fuller, A D Gulson, P M Judd, A J Lowe and J Shaw Occupational Services Department, National Radiological Protection Board, Hospital Lane, Cookridge, Leeds, LS16 6RW, England. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The National Radiological Protection Board (NRPB) is an independent body that has responsibility for advising UK government departments and others on the protection of people from ionising and non-ionising radiation (NIR) hazards. NRPB undertakes research into NIR sources and effects, and provides a comprehensive measurement and advisory service. In addition, NRPB receives many thousands of enquiries each year from individuals who are concerned about their exposure to radio waves, particularly those emitted by mobile phone base stations at around 900 and 1800 MHz. This paper describes the response to one such enquiry from a Member of Parliament (MP) representing local community groups and residents, who were concerned about emissions from three large telecommunications installations close to their homes and local schools. A survey of the radio wave exposure in the area around the three installations was carried out, measuring the total exposures due to all radio signals from 30 MHz to 18 GHz, using a variety of antennas connected to a spectrum analyser. The measurement range was chosen to include all the emissions from the local transmitters, including mobile phone base stations, emergency services' radiocommunications, pagers and microwave dishes. Emissions from transmitters further away, such as broadcast television and radio signals, were also detected. The results are compared against the guidelines published by the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP). -

May 2021 FOI 2387-21 Drink Spiking

Our ref: 2387/21 Figures for incidents of drink spiking in your region over the last 5 years (year by year) I would appreciate it if the figures can be broken down to the nearest city/town. Can you also tell me the number of prosecutions there have been for the above offences and how many of those resulted in a conviction? Please see the attached document. West Yorkshire Police receive reports of crimes that have occurred following a victim having their drink spiked, crimes such as rape, sexual assault, violence with or without injury and theft. West Yorkshire Police take all offences seriously and will ensure that all reports are investigated. Specifically for victims of rape and serious sexual offences, depending on when the offence occurred, they would be offered an examination at our Sexual Assault Referral Centre, where forensic samples, including a blood sample for toxicology can be taken, with the victim’s consent, if within the timeframes and guidance from the Faculty for Forensic and Legal Medicine. West Yorkshire Police work with support agencies to ensure that all victims of crime are offered support through the criminal justice process, including specialist support such as from Independent Sexual Violence Advisors. Recorded crime relating to spiked drinks, 01/01/2016 to 31/12/2020 Notes Data represents the number of crimes recorded during the period which: - were not subsequently cancelled - contain the search term %DR_NK%SPIK% or %SPIK%DR_NK% within the crime notes, crime summary and/or MO - specifically related to a drug/poison/other noxious substance having been placed in a drink No restrictions were placed on the type of drink, the type of drug/poison or the motivation behind the act (i.e. -

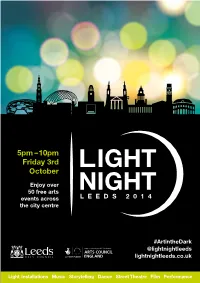

5Pm – 10Pm Friday 3Rd October

w w 5pm – 10pm Friday 3rd October Enjoy over 50 free arts events across the city centre #ArtintheDark @lightnightleeds lightnightleeds.co.uk Light Installations Music Storytelling Dance Street Theatre Film Performance Get Around UNIVERSITY BROTHERTON PARKINSON W LIBRARY BUILDING O Light Night: 1-53 50 O D H STANLEY 49 O There are lots of ways to enjoy the & AUDREY U S many events at Light Night. Create BURTON GALLERY E your own trail using this fold out L N map or join in with one of the MICHAEL D 52 R many guided walks or runs. SADLER H S BUILDING I 5 D W M N A I E L N V K CLOTHWORKERS A CENTENARY C HALL 53 51 3 STAGE @ LEEDS PORTLAND 45-46 W I L Y L O A QUEEN E W T BUILDING W E R D N R A N SQUARE A C E A L R L D 5 T T R 2 I W M O P A I P W L N COLLEGE Y Y O D O N W A K A C L A R E N OF ART O L 47 D C H FIRST DIRECT CIVIC O HALL U M ARENA S E 1 R E R T I L O S MERRION 6-8 N N CENTRE W Y CITY A Y E 1 MUSEUM E L 2 48 N W R A L MILLENNIUM O E E O V SQUARE D ST ANNES A L 4-5 D W A THE CATHEDRAL H M E R R I O N S T C CARRIAGEWORKS O E G R E A T G E O R G E S T 31 U ST JOHN’S T 27 S A L CHURCH E G T P NATION OF SHOPKEEPERS G S 32-34 I L 29 D RENEGADE R A E R B N 19-21 G 28 HOWARD O 22-25 E D DORTMUND W F 26 ASSEMBLY ROOMS I SQUARE E X 9-12 HENRY R N O THE ART GALLERY K 30 TOWN HALL CENTRAL MOORE LIGHT H E O T H E A D R O W A T E L S T G LIBRARY E A O A 15 NORTHERN 17-18 T THE CORE E VICTORIA GARDENS C N BALLET E N D T VICTORIA H E H E S WEST YORKSHIRE A E A D R O W S QUARTER T PLAYHOUSE R L O W E H E A D R A L P T H E B I L O N P L A C T E -

Vase from Burmantofts Pottery Surfaces

Ceramics Selection of interesting Burmantofts animal models including spoon warmers. Estimates £100-400 each. Pair of pink ground Burmantofts bottle vases. Estimate £200-300. Burmantofts lustre vase decorated with fish. Estimate £300-500. Burmantofts lustre plaque decorated with a griffin. Estimate £300-500. Massive and impressive Burmantofts Persian ware vase designed by Leonard King and painted with fish. Estimate £6000-8000. Pictures courtesy of Bonhams, Yorkshire. Large Burmantofts vases moulded and painted Selection of Burmantofts Persian ware vases with flowers. Estimates £200-300 each. by Leonard King. Estimates £300-800. Vase from Burmantofts Pottery surfaces Editor’s comments after a century to head Bonhams To my knowledge this massive and magnificent vase, shown above and to the left, could break the Burmantofts record at auction when Yorkshire sale in November it comes up for sale on the 29th November. Standing at 74 centimetres in height, that is, over 29 inches it would dominate any Bonhams Yorkshire sale to be held at the Pavilions in setting and represents, in its potting, in its decoration and in its firing, the very pinnacle of ceramic achievement. In the field of Harrogate on 25th November includes a massive and pottery and porcelain big is nearly always best. Rarely would any magnificent vase painted in the Persian style with swimming factory produce a masterpiece of this size and quality. Additionally fish designed by Leonard King. a collection of around one hundred pieces of Burmantofts from a The vase measures 74cm high and is 51cm wide and is south coast collection is returning to Yorkshire and I have no doubt expected to realise £6000-8,000. -

The State of Men's Health in Leeds

The State of Men’s Health in Leeds: Data Dr. Amanda Seims, Leeds Beckett University Professor Alan White, Leeds Beckett University 1 2 To reference this document: Seims A. and White A. (2016) The State of Men’s Health in Leeds: Data Report. Leeds: Leeds Beckett University and Leeds City Council. ISBN: 978-1-907240-64-5 This study was funded by Leeds City Council Acknowledgements We would like to thank the following individuals for their input and feedback and also for their commitment to men’s health in Leeds: Tim Taylor and Kathryn Jeffries Dr Ian Cameron DPH and Cllr Lisa Mulherin James Womack and Richard Dixon - Leeds Public Health intelligence team 1 Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction and data analyses .................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Analysis of routinely collected health, socio-economic and service use data ............................. 9 2 The demographic profile of men in Leeds ................................................................................. 10 2.1 The male population ................................................................................................................... 10 2.2 Population change for Leeds ...................................................................................................... 11 2.3 Ethnic minority men in Leeds ....................................................................................................