Community Report Kingston, Frontenac, Lennox & Addington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Market Rent Index & Indices for Non-Profit Projects

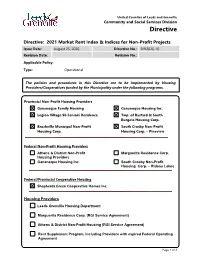

United Counties of Leeds and Grenville Community and Social Services Division Directive Directive: 2021 Market Rent Index & Indices for Non-Profit Projects Issue Date: August 25, 2020 Directive No.: DIR2020-10 Revision Date: Revision No.: Applicable Policy: Type: Operational The policies and procedures in this Directive are to be implemented by Housing Providers/Cooperatives funded by the Municipality under the following programs. Provincial Non-Profit Housing Providers Gananoque Family Housing Gananoque Housing Inc. Legion Village 96 Seniors Residence Twp. of Bastard & South Burgess Housing Corp. Brockville Municipal Non-Profit South Crosby Non-Profit Housing Corp. Housing Corp. – Pineview Federal Non-Profit Housing Providers Athens & District Non-Profit Marguerita Residence Corp. Housing Providers Gananoque Housing Inc. South Crosby Non-Profit Housing Corp. – Rideau Lakes Federal/Provincial Cooperative Housing Shepherds Green Cooperative Homes Inc. Housing Providers Leeds Grenville Housing Department Marguerita Residence Corp. (RGI Service Agreement) Athens & District Non-Profit Housing (RGI Service Agreement) Rent Supplement Program, including Providers with expired Federal Operating Agreement Page 1 of 3 United Counties of Leeds and Grenville Community and Social Services Division Directive Directive: 2021 Market Rent Index & Indices for Non-Profit Projects Issue Date: August 25, 2020 Directive No.: DIR2020-10 Revision Date: Revision No.: BACKGROUND Each year, the Ministry provides indices for costs and revenues to calculate subsidies under the Housing Services Act (HSA). The indices to be used for 2021 are contained in this directive. PURPOSE The purpose of this directive is to advise housing providers of the index factors to be used in the calculation of subsidy for 2021. ACTION TO BE TAKEN Housing providers shall use the index factors in the table below to calculate subsidies under the Housing Services Act, 2011 (HSA) on an annual basis. -

Gathering Communities Making Connections

Gathering Communities Making Connections Tyendinaga/Deseronto / Napanee Kingston Sharbot Lake & Area / Bancroft Guide for Indigenous Families and Children Inside you will find Indigenous Services Indigenous Community Groups & Annual Events Key General Services for Families & Children March, 2014 Updating the Guide This guide is a living document. Listings were suggested by community members and there was no selection or editorial committee. We have tried to ensure the guide is accurate and up-to-date. We do not endorse, promote or favor any particular organization person or event. We plan to update the guide every 6 months. Please e-mail, call or text additions, corrections or deletions to Kate Brant 613 354-8937 (landline) or 613 391-7130 (cell) or [email protected] . Once the Guide is updated we will disseminate by way of the internet, websites, email lists. Gathering Community Making Connections guide was compiled by the Aboriginal Services Working Group: Don Amos Northern Frontenac Community Services Margo Beach Pathways for Children and Youth Sharon Beaudin Aboriginal Prenatal Nutrition Program Kate Brant NACHC, Indigenous Health Program Sarah Brown Aboriginal Health Babies, Healthy Children Maureen Buchanan NACHC, Indigenous Health Program Pam Kent PEL&A Social Services Carol Loft Tipi Moza Judith Moses Planner, KFL&A Children & Youth Services Planning Committee Susan Potvin KFL&A Public Health Susan Ramsay Kingston Literacy & Skills – Aboriginal Literacy Circle Midge Rouse Hotel Dieu Hospital Angelique Tamblyn County of Frontenac Nicola Thomas St. Lawrence College Thomas Thompson Métis Nation of Ontario Peter Tytler Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte Shelley Sayle Udall Pathways for Children & Youth Steve Woodman Family & Children Services of Frontenac, Lennox &Addington 2 Introduction What is the Purpose of this Guide? This is a one-of-a-kind Guide to help you connect to Indigenous Communities in Kingston, Tyendinaga, Napanee & Deseronto, Sharbot Lake and Bancroft. -

Napanee Limestone Plain Important Bird Area Conservation Plan

Napanee Limestone Plain Important Bird Area Conservation Plan Written for the Steering Committee and Stakeholders August 2004 Conservation Plan for the Napanee Limestone Plain IBA August, 2004 Acknowledgements The Important Bird Area (IBA) Program is part of the Natural Legacy 2000 program, a nation-wide initiative to conserve wildlife and habitats on private and public lands. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada's Millennium Partnership Program. We also gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation to Great Lakes Basin Important Bird Areas. Nature Canada (formerly known as the Canadian Nature Federation) and Bird Studies Canada are the Canadian co-partners of BirdLife International, who jointly deliver the Important Bird Areas Program in Canada. Ontario Nature is responsible for site conservation planning in Ontario IBAs. Funding for writing this conservation plan came from Nature Canada through the Government of Canada’s Habitat Stewardship Program. The following people have contributed to this conservation plan in their comments, review, and through meetings with the IBA steering committee: Mike Evans Chris Grooms Kurt Hennige The following organizations have contributed to and/or supported the development of this conservation plan: Bird Studies Canada Canadian Cattlemen’s Association Canadian Wildlife Service Cataraqui Region Conservation Authority Ducks Unlimited Canada Eastern Loggerhead Shrike Recovery Action Group Hastings Stewardship Council Kingston Field Naturalists Lennox and Addington Community Stewardship Council Loyalist Township Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte Nature Canada Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources Ontario Nature-Federation of Ontario Naturalists The Town of Greater Napanee Township of Stone Mills Township of Tyendinaga Suggested citation D. -

04 Kingston Times.Indd

SPEND Passion Four more Harper visits and resolve years Winter storm does its business on area TIME Woodstock Mayor Noble WISELY Women’s March says he’ll seek with draws hundreds another term Almanac Weekly REGION > 3 ELECTION 2019 > 4 PHOTOS > 10 THURSDAY, JANUARY 24, 2019 VOLUME 14; ISSUE 4 ULSTER PUBLISHING, INC. WWW.HUDSONVALLEYONE.COM KINGSTON TIMES ONE DOLLAR FIFTY CENTS ELECTION 2019 Rounds for judge Kingston defense attorney wants Don Williams’ seat on the bench BY JESSE J. SMITH t a sentencing hearing briefly to the defense table and attorney for convicted murderer Seth Bryan Rounds. “Some would say too long.” Lyons last month, County On Friday, Rounds lifted the veil on the Court Judge Donald Williams worst-kept secret in Ulster County legal A was about to offer some advice circles when he announced that he would to the victim’s family on how to begin heal- seek election to the county judgeship. ing from the brutal killing of their loved “I believe that everything in my person- one. The judge, about to enter his 10th al life and professional career has prepared year on the bench, prefaced his remarks me for this office at this moment in time,” PHOTO PROVIDED DAN BARTON with the words, “I have been doing this said Rounds, 49, of the Town of Ulster. Bryan Rounds. Judge Don Williams. a long time.” Then Williams cast his eyes (continued on page 6) CITY GOVERNMENT No contract yet for city police Shrinking officer ranks, three-year stalemate damaging morale, says PBA president BY JESSE J. -

The Canadian Parliamentary Guide

NUNC COGNOSCO EX PARTE THOMAS J. BATA LI BRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY us*<•-« m*.•• ■Jt ,.v<4■■ L V ?' V t - ji: '^gj r ", •W* ~ %- A V- v v; _ •S I- - j*. v \jrfK'V' V ■' * ' ’ ' • ’ ,;i- % »v • > ». --■ : * *S~ ' iJM ' ' ~ : .*H V V* ,-l *» %■? BE ! Ji®». ' »- ■ •:?■, M •* ^ a* r • * «'•# ^ fc -: fs , I v ., V', ■ s> f ** - l' %% .- . **» f-•" . ^ t « , -v ' *$W ...*>v■; « '.3* , c - ■ : \, , ?>?>*)■#! ^ - ••• . ". y(.J, ■- : V.r 4i .» ^ -A*.5- m “ * a vv> w* W,3^. | -**■ , • * * v v'*- ■ ■ !\ . •* 4fr > ,S<P As 5 - _A 4M ,' € - ! „■:' V, ' ' ?**■- i.." ft 1 • X- \ A M .-V O' A ■v ; ■ P \k trf* > i iwr ^.. i - "M - . v •?*»-• -£-. , v 4’ >j- . *•. , V j,r i 'V - • v *? ■ •.,, ;<0 / ^ . ■'■ ■ ,;• v ,< */ ■" /1 ■* * *-+ ijf . ^--v- % 'v-a <&, A * , % -*£, - ^-S*.' J >* •> *' m' . -S' ?v * ... ‘ *•*. * V .■1 *-.«,»'• ■ 1**4. * r- * r J-' ; • * “ »- *' ;> • * arr ■ v * v- > A '* f ' & w, HSi.-V‘ - .'">4-., '4 -' */ ' -',4 - %;. '* JS- •-*. - -4, r ; •'ii - ■.> ¥?<* K V' V ;' v ••: # * r * \'. V-*, >. • s s •*•’ . “ i"*■% * % «. V-- v '*7. : '""•' V v *rs -*• * * 3«f ' <1k% ’fc. s' ^ * ' .W? ,>• ■ V- £ •- .' . $r. « • ,/ ••<*' . ; > -., r;- •■ •',S B. ' F *. ^ , »» v> ' ' •' ' a *' >, f'- \ r ■* * is #* ■ .. n 'K ^ XV 3TVX’ ■■i ■% t'' ■ T-. / .a- ■ '£■ a« .v * tB• f ; a' a :-w;' 1 M! : J • V ^ ’ •' ■ S ii 4 » 4^4•M v vnU :^3£'" ^ v .’'A It/-''-- V. - ;ii. : . - 4 '. ■ ti *%?'% fc ' i * ■ , fc ' THE CANADIAN PARLIAMENTARY GUIDE AND WORK OF GENERAL REFERENCE I9OI FOR CANADA, THE PROVINCES, AND NORTHWEST TERRITORIES (Published with the Patronage of The Parliament of Canada) Containing Election Returns, Eists and Sketches of Members, Cabinets of the U.K., U.S., and Canada, Governments and Eegisla- TURES OF ALL THE PROVINCES, Census Returns, Etc. -

CITY of KINGSTON RE-ENVISION PUBLIC SAFETY TASK FORCE FINAL REPORT January 22, 2021

CITY OF KINGSTON RE-ENVISION PUBLIC SAFETY TASK FORCE FINAL REPORT January 22, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from Mayor Steve Noble .................................................................................. 3 Task Force Members and Support Staff .................................................................... 4-5 The Process ................................................................................................................ 6 Executive Overview ................................................................................................. 7-9 Use of Force & Accountability ● Re-envisioning the Kingston Police Commission ........................................ 11-19 by Minya DeJohnette ● Police Accountability & Discipline ............................................................. 20-23 by Andrea Callan ● Community Awareness of Police Policies & Procedures .................................. 24 by Daniel Gruner Alternatives to Direct Police Response ● Mental Health and Addiction-related Issues .............................................. 26-27 by David McNamara ● Building a Supportive and Rehabilitative Criminal Justice System .............. 28-32 by Raquel Derrick, PhD ● Implement LEO Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) Training ............................. 33-37 by Beetle Bailey Recruitment, Training & Morale ● Improving Morale within the KPD .................................................................. 39 by Chief Egidio Tinti ● Addressing Unconscious Bias ................................................................... -

City Council Agenda

City of Kingston Information Report to Council Report Number 21-149 To: Mayor and Members of Council From: Lanie Hurdle, Chief Administrative Officer Resource Staff: Corporate Management Team and City Directors Date of Meeting: June 1, 2021 Subject: Strategic Plan Quarterly Report Q1 2021 Council Strategic Plan Alignment: Theme: Corporate business Goal: See above Executive Summary: The purpose of this report is to provide Council with a progress update as of the first quarter of 2021, for the work outlined in the 2019-2022 Council Strategic Plan approved in May 2019 (Report Number 19-133). Progress updates on the strategic plan are provided to Council on a quarterly basis and the community is informed through the City’s Strategic Plan website. The Q1 2021 progress update is attached as Exhibit A to this report. This report also provides an update on the Council motions and petitions (Exhibit B) that have been debated and passed since December 2018 and as of March 31, 2021. Recommendation: This report is for information only. Information Report to Council Report Number 21-149 June 1, 2021 Page 2 of 4 Authorizing Signatures: Lanie Hurdle, Chief Administrative Officer Consultation with the following Members of the Corporate Management Team: Paige Agnew, Commissioner, Community Services Peter Huigenbos, Commissioner, Business, Environment & Projects Brad Joyce, Commissioner, Corporate Services Jim Keech, President & CEO, Utilities Kingston Desirée Kennedy, Chief Financial Officer & City Treasurer Sheila Kidd, Commissioner, Transportation -

A Discussion of Kingston and Area's Historic Small Houses Known As “The Ontario Cottage” Type1

ANALYSIS | ANALYSE A DISCUSSION OF KINGSTON AND AREA’S HISTORIC SMALL HOUSES KNOWN AS “THE ONTARIO COTTAGE” TYPE1 JENNIFER MCKENDRY’s Ph.D. thesis (University > JENNIFER MCKENDRY of Toronto) was on Kingston’s architecture from 1835 to 1865. She is a freelance lecturer and researcher on such projects as the Frontenac County Court House, Kingston Penitentiary, and Kingston City Hall. Her publications include: “Yon cottage seems a bower of bliss, Into the Silent Land: Historic Cemeteries and A covert for protection Of tender thought, that nestle there – Graveyards in Ontario (2003, Kingston, by The brood of chaste affection.” the author); Portsmouth Village, Kingston: an – William Wordsworth, Illustrated History (2010, Kingston, by the “Yarrow Visited, September, 1814.” author); Early Photography of Kingston from the Postcard to the Daguerreotype (2013, Kingston, he term “the Ontario Cottage” is by the author); With Our Past before Us: Tone invented by secondary sources 19th-Century Architecture in the Kingston Area resulting in some confusion about which (1995, Toronto, University of Toronto Press); historical buildings fit this term. There and Modern Architecture in Kingston: a Survey is also confusion over today’s North American meaning of a cottage as “a of 20th-Century Buildings (2014, Kingston, by dwelling used for vacation purposes, usu- the author). ally located in a rural area near a lake or river,” as defined by the Canadian Oxford Dictionary. An alternative definition for Britain in the same dictionary is “a small simple house, especially in the country.” A small simple house was the position advocated by Andrew Jackson Downing [1815-1852], an American whose writ- ings strongly influenced architecture in the United States and Canada. -

Opting out of Cannabis Retail Stores

OPTING OUT OF CANNABIS RETAIL STORES As per Ontario Regulation 468/18, municipalities must notify the AGCO of their decision to opt out by having the municipal Clerk, Chief Administrative Officer or Mayor send the AGCO Registrar written notification that the municipality has passed a resolution prohibiting cannabis retail stores. This written notification must be sent by email to [email protected] and received by the AGCO no later than January 22, 2019. The notification must include: 1. The official name of the municipality, and; 2. The date the resolution was passed. Once received, the AGCO will acknowledge receipt by email. A municipality that decides to prohibit cannabis retail stores may later reverse its decision; however, under the Cannabis Licence Act, 2018, a decision by a municipality to allow cannabis retail stores is final and may not be subsequently reversed. OPTING IN TO ALLOW RETAIL CANNABIS STORES If at any time before January 22, 2019, a municipality decides it will allow cannabis retail stores within its jurisdiction they are encouraged to notify the AGCO as soon as possible. Early notification to the AGCO, using the [email protected] email, will not change the earliest date that licensed retail stores may open, which remains April 1, 2019. If the AGCO does not receive written notification from a municipality by January 22, 2019 they will be considered to be allowing cannabis retail stores by default. INFORMATION FOR ONTARIO MUNICIPALITIES ABOUT CANNABIS RETAIL STORE LICENSING The maximum 25 Retail Store Authorizations will be allocated in accordance with Ontario Regulation 468/18, which provides for the maximum number of stores in the following Regions: a. -

Map 21 Land Use

292,000 312,000 332,000 352,000 372,000 0 0 0 0 0 0 , , 0 0 8 Townships of Tudor & Cashel 8 9 9 , , 4 4 Township of North Frontenac 0 0 0 0 0 0 , , 0 0 6 6 9 9 , , 4 Townships of Tudor & Cashel Township of Addington Highlands 4 TOWNSHIP OF CENTRAL FRONTENAC 38 0 0 0 Municipality of Tweed 0 0 0 , , 0 0 4 Township of Madoc 4 9 9 , , 4 4 7 41 Madoc Township of South Frontenac Tweed Township of Stone Mills 0 0 0 0 0 0 , Municipality of Centre Hastings , 0 0 2 2 9 9 , , 4 4 Township of Stirling-Rawdon 37 14 Township of Tyendinaga Town of Greater Napanee Loyalist Township 0 Napanee 0 0 City of Belleville 0 0 0 , , 0 0 0 0 9 401 9 , , 4 4 Town of Deseronto City of Quinte West Deseronto Belleville 2 Legend 62 0 0 0 Agriculture 0 0 0 , , 0 0 8 8 8 8 , City Business District , 4 4 Commercial County of Prince Edward Flood Picton Bloomfield Community Facility 33 Residential Wellington Industrial Industrial railway allowance Ministry aggriculture 0 Mineral Aggregate 0 0 0 0 0 , , 0 Recreation Commercial 0 6 6 8 8 , 1:375,000 , 4 Lake Ontario 4 Rural 0 2.5 5 10 Kilometers Open Space 292,000 312,000 332,000 352,000 372,000 Legend Highway 401 Rivers County Boundaries Populated Areas d x m . 6 0 V _ e s U d n a L _ 1 Highways Lakes Township Boundaries Quinte Region 2 _ # p a M C Moira River, Napanee Region and Prince Edward Region Watersheds. -

Police in Ontario Police Associations OPP Detachments

Email Contact List – Police in Ontario Police Associations OPP Detachments Note: This is a list of all known email addresses for Police in Ontario. It is meant for informational purposes only. It is not meant for anyone to send numerous emails to the Police, which could be interpreted as harassment. We encourage respectful communication for any interaction with the Police, no matter which province/territory they reside in. ~ thank you….Stand Up Canada List of Ontario Police Associations - Alphabetical Order Police Association of Ontario PAO Contacts: You can reach the Police http://www.pao.ca Association of Ontario via the following channels: Mail:2 Carlton Street, Suite 901. Toronto, ON There are 46 in Ontario M5B 1J3 Phone: 416.487.9367 We were only able to find 35 email addresses Email:[email protected] For media inquiries, please contact [email protected]. 46 ONTARIO POLICE ASSOCIATIONS 34 KNOWN EMAIL ADDRESSES Copy & Paste ALL or INDIVIDUAL Akwesasne [email protected] Aylmer [email protected] Barrie [email protected] Belleville Brantford [email protected] Brockville [email protected] Chatham-Kent [email protected] Cobourg [email protected] Cornwall Deep River [email protected] Dryden [email protected] Durham Regional [email protected] Gananoque [email protected] Guelph Halton Region [email protected] Hamilton [email protected] Hanover Kingston City [email protected] Lasalle [email protected] Published: May 10, 2021 Page 1 of 5 Lindsay [email protected] London [email protected] Niagara Parks Niagara Region [email protected] North Bay [email protected] Ontario Provincial Police [email protected] Ottawa [email protected] Owen Sound [email protected] Peel Regional [email protected] Peterborough [email protected] Port Hope [email protected] Sarnia [email protected] Saugeen Shores Sault Ste. -

Committee of Adjustment

TOWN OF GREATER NAPANEE COMMITTEE OF ADJUSTMENT A G E N D A NOVEMBER 27, 2018 at 6:45 p.m. Council Chambers, Town Hall - 124 John St., Napanee Page 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. ADOPTION OF AGENDA 2.1 Adopt Agenda Recommendation: That the Agenda of the Committee of Adjustment dated November 27, 2018 be adopted as presented. 3. DISCLOSURE OF PECUNIARY INTEREST & THE GENERAL NATURE THEREOF 4. ADOPTION OF MINUTES 5 - 8 4.1 Committee of Adjustment - November 13, 2018 Recommendation: That the minutes of the Committee of Adjustment dated November 13, 2018 be received and adopted. 5. LAND SEVERANCE APPLICATIONS 9 - 27 5.1 Land Severance Application PLCON 2017 020 D. & M. Bradfield, 2935 County Road 9 Legal Description - CON 5 PT LOT 14 Recommendation: That the committee change the conditions of the previously granted consent for PLCON 2017 020 to add the following condition: “a development agreement be entered into with the municipality whereby the owner agrees to execute conditions b) through i) prior to December 1, 2019” And further; that the committee deem the above noted change to be minor thereby requiring no further Notice of changing conditions. 28 - 42 5.2 Land Severance Application PLCOR 2018 056 M. Carroll, 470 County Road 9 Legal Description - CON 4 PT LOT 11 RP 29R7963 PART 1 Recommendation: That Land Severance Application PLCOR 2018 056 to permit a lot addition of 1,653 m² be approved subject to the following conditions: 1) That taxes be paid in full; 2) That the parcel is to be added to the property identified as Roll No.