ECCD-F1KD Situation Analysis in Selected KOICA-UNICEF Municipalities in Northern Samar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EASTERN VISAYAS: SUMMARY of REHABILITATION ACTIVITIES (As of 24 Mar)

EASTERN VISAYAS: SUMMARY OF REHABILITATION ACTIVITIES (as of 24 Mar) Map_OCHA_Region VIII_01_3W_REHAB_24032014_v1 BIRI PALAPAG LAVEZARES SAN JOSE ALLEN ROSARIO BOBON MONDRAGON LAOANG VICTORIA SAN CATARMAN ROQUE MAPANAS CAPUL SAN CATUBIG ANTONIO PAMBUJAN GAMAY N O R T H E R N S A M A R LAPINIG SAN SAN ISIDRO VICENTE LOPE DE VEGA LAS NAVAS SILVINO LOBOS JIPAPAD ARTECHE SAN POLICARPIO CALBAYOG CITY MATUGUINAO MASLOG ORAS SANTA GANDARA TAGAPUL-AN MARGARITA DOLORES SAN JOSE DE BUAN SAN JORGE CAN-AVID PAGSANGHAN MOTIONG ALMAGRO TARANGNAN SANTO PARANAS NI-O (WRIGHT) TAFT CITY OF JIABONG CATBALOGAN SULAT MARIPIPI W E S T E R N S A M A R B I L I R A N SAN JULIAN KAWAYAN SAN SEBASTIAN ZUMARRAGA HINABANGAN CULABA ALMERIA CALBIGA E A S T E R N S A M A R NAVAL DARAM CITY OF BORONGAN CAIBIRAN PINABACDAO BILIRAN TALALORA VILLAREAL CALUBIAN CABUCGAYAN SANTA RITA BALANGKAYAN MAYDOLONG SAN BABATNGON ISIDRO BASEY BARUGO LLORENTE LEYTE SAN HERNANI TABANGO MIGUEL CAPOOCAN ALANGALANG MARABUT BALANGIGA TACLOBAN GENERAL TUNGA VILLABA CITY MACARTHUR CARIGARA SALCEDO SANTA LAWAAN QUINAPONDAN MATAG-OB KANANGA JARO FE PALO TANAUAN PASTRANA ORMOC CITY GIPORLOS PALOMPON MERCEDES DAGAMI TABONTABON JULITA TOLOSA GUIUAN ISABEL MERIDA BURAUEN DULAG ALBUERA LA PAZ MAYORGA L E Y T E MACARTHUR JAVIER (BUGHO) CITY OF BAYBAY ABUYOG MAHAPLAG INOPACAN SILAGO HINDANG SOGOD Legend HINUNANGAN HILONGOS BONTOC Response activities LIBAGON Administrative limits HINUNDAYAN BATO per Municipality SAINT BERNARD ANAHAWAN Province boundary MATALOM SAN JUAN TOMAS (CABALIAN) OPPUS Municipality boundary MALITBOG S O U T H E R N L E Y T E Ongoing rehabilitation Ongoing MAASIN CITY activites LILOAN MACROHON PADRE BURGOS SAN 1-30 Planned FRANCISCO SAN 30-60 RICARDO LIMASAWA PINTUYAN 60-90 Data sources:OCHA,Clusters 0 325 K650 975 1,300 1,625 90-121 Kilometers EASTERN VISAYAS:SUMMARY OF REHABILITATION ACTIVITIES AS OF 24th Mar 2014 Early Food Sec. -

Republic of the Philippines PROVINCE of ZAMBOANGA DEL NORTE Municipality of President Manuel A

Republic of the Philippines PROVINCE OF ZAMBOANGA DEL NORTE Municipality of President Manuel A. Roxas OFFICE OF THE SANGGUNIANG BAYAN EXCERPT FROM THE MINUTES OF THE REGULAR SESSION OF THE SANGGUNIANG BAYANOF PRESIDENT MANUEL A. ROXAS, ZAMBOANGA DEL NORTE HELD ATTHE ROXAS MUNICIPAL SESSION HALL ON FEBRUARY 19, 2018 PRESENT: Hon. Leonor O. Alberto, Municipal Vice Mayor/ Presiding Officer Hon. Ismael A. Rengquijo, Jr., SB Member/ Floor Leader Hon. Clayford C. Vailoces, SB Member/ 1st Asst. Floor Leader Hon. Lucilito C. Bael, Member Hon. Glicerio E. Cabus, Jr., SB Member Hon. Mark Julius C. Ybanez, SB Member/ President Pro Tempore Hon. Librado C. Magcanta, Sr., SB Member/ 2nd Asst. Floor Leader Hon. Helen L. Bruce, SB Member Hon. Reynaldo G. Abitona, SB Member Hon. Angelita L. Rengquijo, ABC President/ SB Member ABSENT: None “RESOLUTION NO. 68 Series 2018 RESOLUTION AUTHORIZING THE MUNICIPAL MAYOR TO INTERPOSE NO OBJECTION FOR THE PRE PATENT APPLICATION OF THE BARANGAY COUNCIL OF DOHINOB RELATIVE TO THE DEAD ROAD LOCATED AT BARANGAY DOHINOB, THIS MUNICIPALITY WHEREAS, received by the Office of the Sangguniang Bayan was Resolution No. 5, series 2018 of the Barangay Council of Dohinob requesting this Body to interpose no objection of their free patent application on a dead road; WHEREAS, said resolution was referred to the Committee on Laws and based on its findings under Committee Report No. 2018-12 conducted on February 15, 2018, it was recommended to the Sangguniang Bayan to authorize the Municipal Mayor for the aforementioned purpose/s; WHEREFORE, viewed from the foregoing, and On motion of Hon. Clayford C. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA

2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA 201,233 BALER (Capital) 36,010 Barangay I (Pob.) 717 Barangay II (Pob.) 374 Barangay III (Pob.) 434 Barangay IV (Pob.) 389 Barangay V (Pob.) 1,662 Buhangin 5,057 Calabuanan 3,221 Obligacion 1,135 Pingit 4,989 Reserva 4,064 Sabang 4,829 Suclayin 5,923 Zabali 3,216 CASIGURAN 23,865 Barangay 1 (Pob.) 799 Barangay 2 (Pob.) 665 Barangay 3 (Pob.) 257 Barangay 4 (Pob.) 302 Barangay 5 (Pob.) 432 Barangay 6 (Pob.) 310 Barangay 7 (Pob.) 278 Barangay 8 (Pob.) 601 Calabgan 496 Calangcuasan 1,099 Calantas 1,799 Culat 630 Dibet 971 Esperanza 458 Lual 1,482 Marikit 609 Tabas 1,007 Tinib 765 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Bianuan 3,440 Cozo 1,618 Dibacong 2,374 Ditinagyan 587 Esteves 1,786 San Ildefonso 1,100 DILASAG 15,683 Diagyan 2,537 Dicabasan 677 Dilaguidi 1,015 Dimaseset 1,408 Diniog 2,331 Lawang 379 Maligaya (Pob.) 1,801 Manggitahan 1,760 Masagana (Pob.) 1,822 Ura 712 Esperanza 1,241 DINALUNGAN 10,988 Abuleg 1,190 Zone I (Pob.) 1,866 Zone II (Pob.) 1,653 Nipoo (Bulo) 896 Dibaraybay 1,283 Ditawini 686 Mapalad 812 Paleg 971 Simbahan 1,631 DINGALAN 23,554 Aplaya 1,619 Butas Na Bato 813 Cabog (Matawe) 3,090 Caragsacan 2,729 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and -

Palapag-Mapanas-Gamay

\.-7 .- Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS NORTHERI{ SAMAR 2lrD DISTRICT ENGINEERING OFFICE REGIONAL OFFICE t{O. VHI Brgy, Burabud, Laoang, Northern Samar Telephone No./Fax No. 2518254 INVITATION TO BID FOR REMEDIAL MEASURE ON DAMAGED ROAD ALOI{G PAI{GPANG. PALAPAG-MAPANAS-GAMAY-LAPINIG ROAD, CABATUAN-MAGTAON SECTION, KO820+900 The Departsnent of Public works and Highways - Northern Samar Second District Engineering Office, through its Eids and Awards Committee (BAC) invites suppliers to submit bids for the following Contract: Contract ID No. 21Grr0001 Remedial Measure on Damaged Road along Pangpang-Palapag- Contract Name MaDanas-Gamay-Lapiniq Road, Cabatuan-lvaqtaon *ction, K0820+900 Contract Location PalaDao, Northern Samar 1. Installation of additional Four (4) pcs. Reinforced Concrete Pipe Brief Description of Cuivert (RCPC), 910mm diameter (36?) Goods to be Procured 2. Construction of 20 Linear meter Detour, (4.00m x 30.00m) Approved Budget for Pho 499.628.14 the Contract Source of Funds GOP Delivery Date of Goods/Contract 30 Cnlendar Days Durauon Service The BAC is conduding the public bidding for this Contract in accordance with RA 9184 and its Implementing Rules and Regulations. Bidders should have completed, within from the date of submission and receipt of bids, a contract similar to the Project. The description of an eligible bidder is contained in the Bidding Documents, particularty, in Section IV Instrudion to Bidders. To be eligible to bid for this Contract, a supplier must meet the following -

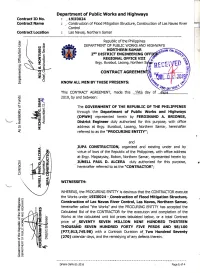

19Ii0024 Contract Agreement

Department of Public works and Highways Contract XD No, | ,49ttoo24 Contract Name | --'Construction of Flmd Mitigation Structure, Construction of Las Navas River Control Contract Location : Las Navas, Northern Samar Republic of the Philippines : DEPARTN4ENT OF PUBUC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS NORTHERN SAMAR 2IID DISTRICT ENGINEERII{G OFF t' o E REGIONAL OFFICE VIII o ? Brgy. Burabud, Laoang, Northern CONTRACT AGREEME E _q E KNOW ALL MEN BY THESE PRESENTSI This coNTMcT AGREEMENT, made this j$!-b day of -E ar 2019, by and between: 6 l,* The GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES E SE through the Department of Public Works and Highways E (DPWH) represented herein by FERDINAND A. BRIONES, " ii -=t U '-.: -ur E€= District Engineer duly authorized for this purpose/ with offce rll address at Brgy. Burabud, Laoang, Northern Samar, hereinafter referred to as the "PROCURING ENTITY"; and JUPA CONSTRUCTION, organized and existing under and by virtue of laws of the Republic of the Philippines, with office address at Brgy. Magsaysay, Bobon, Nor&ern Samar, represented herein by Jflrll paul D. ALCEM duly authorized for this pur@se, i g hereinafter referred to as the "CONTRACTOR"; 8 WITNESSETH; WHEREAS, the PROCURING ENTITY is desirous that the CONTRACTOR execute the Works unde79II0O24 -ronstruction of Flood Mitigation Structure, P '6. Construction of Las Navas River Controlf Las Navas, Nolthern Samar, = hereinafter called "the Works" and the PROCURING ENTITY has accepted the Calculated Bid of the CONTMCTOR for the execution and mmpletion of the s Works at the calculated unit bid prices tabulated below, or a total Contrad oTice of SEVENTY SEVEN MILLION NINE HUNDRED THIRTEEN THOUSA D SEVEN HUNDRED FORTY FIVE PESOS AI{D 98/1OO d (P77,9L3,745,9A) with a Contract Duration of- Two Hundr€d Seventy € (270) calendar days, and the remedying of any defects therein. -

Chec List Amphibians and Reptiles, Romblon Island

Check List 8(3): 443-462, 2012 © 2012 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution Amphibians and Reptiles, Romblon Island Group, central PECIES Philippines: Comprehensive herpetofaunal inventory S OF Cameron D. Siler 1*, John C. Swab 1, Carl H. Oliveros 1, Arvin C. Diesmos 2, Leonardo Averia 3, Angel C. ISTS L Alcala 3 and Rafe M. Brown 1 1 University of Kansas, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Biodiversity Institute, Lawrence, KS 66045-7561, USA. 2 Philippine National Museum, Zoology Division, Herpetology Section. Rizal Park, Burgos St., Manila, Philippines. 3 Silliman University Angelo King Center for Research and Environmental Management, Dumaguete City, Negros Oriental, Philippines. * Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: We present results from several recent herpetological surveys in the Romblon Island Group (RIG), Romblon Province, central Philippines. Together with a summary of historical museum records, our data document the occurrence of 55 species of amphibians and reptiles in this small island group. Until the present effort, and despite past studies, observations of evolutionarily distinct amphibian species, including conspicuous, previously known, endemics like the forestherpetological frogs Platymantis diversity lawtoni of the RIGand P.and levigatus their biogeographical and two additional affinities suspected has undescribedremained poorly species understood. of Platymantis We . reportModerate on levels of reptile endemism prevail on these islands, including taxa like the karst forest gecko species Gekko romblon and the newly discovered species G. coi. Although relatively small and less diverse than the surrounding landmasses, the islands of Romblon Province contain remarkable levels of endemism when considered as percentage of the total fauna or per unit landmass area. -

The Lady L Story Research Vol

Asia Pacific Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, Vol. 4, No. 2, May 2016 _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Asia Pacific Journal of A Life Dedicated to Public Service: Multidisciplinary The Lady L Story Research Vol. 4 No.2, 37-43 Maribeth P. Bentillo1, Ericka Alexis A. Cortes2,Jlayda Carmel Y. Gabor3, May 2016 Florabel C. Navarrete4 Reynaldo B. Inocian5 P-ISSN 2350-7756 Department of Public Governance, College of Arts and Sciences, Cebu Normal E-ISSN 2350-8442 University, Cebu City Philippines, 6000 www.apjmr.com [email protected],[email protected],[email protected], [email protected],[email protected] Date Received: March 10, 2016; Date Revised: May 11, 2016 Abstract-This study featured how a lady local politician rose to power as a barangay captain. It aimed to: describe her leadership orientation before she became a barangay captain, analyze the factors of her success stories in political leadership, extrapolate her values based on the problems/challenges met in the barangay, unveil her initiatives to address these problems, and interpolate her enduring vision for the future of the barangay. Through a biographical research design, with purposive sampling, a key female informant named as Lady L was chosen with the sole criteria of being a female Barangay Captain of Cebu City. Interview guides were utilized in the generation of Lady L’s biographic information about her political career.Lady L’s experiences in waiting for the perfect time and working in the private sector destined her to have a successful political career enhanced with passion and family influence. Encountering problems concerning basic education and unwanted migrants in Barangay K did not discourage her choice to run for re-election, because of her dedication to public service. -

Directory of Participants 11Th CBMS National Conference

Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Academe Dr. Tereso Tullao, Jr. Director-DLSU-AKI Dr. Marideth Bravo De La Salle University-AKI Associate Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 Ms. Nelca Leila Villarin E-Mail: [email protected] Social Action Minister for Adult Formation and Advocacy De La Salle Zobel School Mr. Gladstone Cuarteros Tel No: (02) 771-3579 LJPC National Coordinator E-Mail: [email protected] De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 7212000 local 608 Fax: 7248411 E-Mail: [email protected] Batangas Ms. Reanrose Dragon Mr. Warren Joseph Dollente CIO National Programs Coordinator De La Salle- Lipa De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 756-5555 loc 317 Fax: 757-3083 Tel No: 7212000 loc. 611 Fax: 7260946 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Camarines Sur Brother Jose Mari Jimenez President and Sector Leader Mr. Albino Morino De La Salle Philippines DEPED DISTRICT SUPERVISOR DEPED-Caramoan, Camarines Sur E-Mail: [email protected] Dr. Dina Magnaye Assistant Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Cavite Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 E-Mail: [email protected] Page 1 of 78 Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Ms. Rosario Pareja Mr. Edward Balinario Faculty De La Salle University-Dasmarinas Tel No: 046-481-1900 Fax: 046-481-1939 E-Mail: [email protected] Mr. -

The Socio-Economic Impact of the Help for Catubig Agricultural Advancement Project (Hcaap)

[Ocaña *, Vol.7 (Iss.5): May 2019] ISSN- 2350-0530(O), ISSN- 2394-3629(P) DOI: https://doi.org/10.29121/granthaalayah.v7.i5.2019.830 Social THE SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACT OF THE HELP FOR CATUBIG AGRICULTURAL ADVANCEMENT PROJECT (HCAAP) Eduardo L. Ocaña Jr. *1 *1 Department of Social Sciences, College of Arts and Communication, University of Eastern Philippines, Catarman, Northern Samar, Philippines 6400 Abstract Development must not only focus on economic growth expressed in rosy figures of GDP and GNP. The economic gains of the rich as expected by economists, must “trickle down” down to the grass roots. It is along this reality that prompted the national government and development planners to look for strategy in which the marginalized which constitute the biggest number of the population in the Third World countries become recipients of development initiatives. Northern Samar, one of the poorest provinces in the Philippines, has been a recipient of the Help for Catubig Agricultural Advancement Project (HCAPP), a project of 5.2 billion yen or 3.4 billion in pesos allocating 2.4 billion pesos alone to irrigate 4, 550 hectares of agricultural lands to spur agricultural development in the Catubig Valley area of Northern Samar. This research aimed to determine the level of socio-economic impact of the HCAAP and related problems. The areas covered by the HCAAP were the Municipalities of Catubig and Las Navas both located in the Catubig Valley. A descriptive-evaluative study, utilized quantitative techniques like survey employing interview schedule for data collection and analyses. The respondents were beneficiaries from Municipality of Catubig, and Las Navas. -

Download Rock Biri!

Guardian rocks of old, alive Carved by water, hewn by time Reaching out to sun and sky Grand in scale, in form and height I swim her shallow pools and sigh In awe of her beautiful lagoons Secrets hidden in boulders grand In this little paradise of man Guardian rocks of old, alive Cleaved by winds, scorched by fire Kissed but unmelted by the sun A place for solace and for fun Come marvel at these boulders’ feet Sentinels of the Philippine sea Found in this island called Biri Wonders await for you to see The amazing rock structures of Biri Biri, Northern Samar © Isla Snapshots time, when water shaves centuries off your surface — ancient, modern art More than the rocks Visitors may swim in the small pockets of © Foz Brahma Mangrove City Since 2007 the community has continously improve © Isla Snapshots shallow pools that formed in the rocks particularly in Bel-At or do the mangrove ecosystem covering and protecting over 500 hectares. other water activities like surfing. Bird-watching is also a growing popular activity. Magsapad Rock Formation The rock formations were named after © Isla Snapshots Magsapad Rock Formation The rock formations were named after © Yoshke Dimen Best playground on earth Children play at the shallow area near the © Isla Snapshots the shapes they took as imagined by the town folks. the shapes they took as imagined by the town folks. shore with Mount Bulusan as backdrop. 2 PwC Philippines VisMin’s Philippine Gems 3 Philippine Biri Rock Formation Parola Sea 1 Magasang 1 Biri, Northern Samar, Visayas 2 2 Magsapad 3 4 5 3 Makadlaw 6 4 Puhunan Geography and people 7 5 Bel-At 6 Caranas Biri is a fifth class municipality in the 7 Inanahawan province of Northern Samar, Visayas, Cogon Philippines. -

List of Pamb Members Enbanc

LIST OF PAMB MEMBERS ENBANC NAME AND DESIGNATION NAME OF AGENCY LGU's/NGO's/OGA's 1. DR. CORAZON B. GALINATO, CESO, IV Regional Executive Director PAMB Chairman DENR BELEN O. DABA Regional Technical Director for PAWCZMS 2. HON. JUANIDY M. VIÑA Municipal Mayor LGU CONCEPCION 3. HON. DONJIE D. ANIMAS Municipal Mayor LGU SAPANG DALAGA 4. HON. SVETLANA P. JALOSJOS Municipal Mayor LGU BALIANGAO 5. HON. LUISITO B. VILLANUEVA, JR. Municipal Mayor LGU CALAMBA 6. HON AGNES V. VILLANUEVA Municipal Mayor LGU PLARIDEL 7. HON. MARTIN C. MIGRIÑO Municipal Mayor LGU LOPEZ JAENA 8. HON. JASON P. ALMONTE City Mayor CITY OF OROQUIETA 9. HON. JIMMY R. REGALADO Municipal Mayor LGU ALORAN 10. HON. MERIAM L. PAYLAGA Municipal Mayor LGU PANAON 11. HON. RANULFO B. LIMQUIMBO Municipal Mayor LGU JIMENEZ 12. HON. DELLO T. LOOD Municipal Mayor LGU SINACABAN 13. HON. ESTELA R. OBUT-ESTAÑO Municipal Mayor LGU TUDELA 14. HON. DAVID M. NAVARRO Municipal Mayor LGU CLARIN 15. HON. NOVA PRINCESS P. ECHAVEZ City Mayor CITY OF OZAMIZ 16. HON. PHILIP T. TAN City Mayor CITY OF TANGUB 17. HON. SAMSON R. DUMANJUG Municipal Mayor LGU BONIFACIO 18. HON. RODOLFO D. LUNA Municipal Mayor LGU DON VICTORIANO 19. HON. DARIO S. LAPORE Brgy. Gandawan, Barangay Captain Don Victoriano 20. HON. EMELIO C. MEDEL Brgy. Mara-mara, Don Barangay Captain Victoriano 21 HON. JOMAR ENDING Brgy. Lake Duminagat, Don Barangay Captain Victoriano 22. HON. ROMEO M. MALOLOY-ON Brgy. Lalud, Don Victoriano Barangay Captain 23. HON. ROGER D. ACA-AC Brgy. Liboron, Don Victoriano Barangay Captain 24. HON. -

MAKING the LINK in the PHILIPPINES Population, Health, and the Environment

MAKING THE LINK IN THE PHILIPPINES Population, Health, and the Environment The interconnected problems related to population, are also disappearing as a result of the loss of the country’s health, and the environment are among the Philippines’ forests and the destruction of its coral reefs. Although greatest challenges in achieving national development gross national income per capita is higher than the aver- goals. Although the Philippines has abundant natural age in the region, around one-quarter of Philippine fami- resources, these resources are compromised by a number lies live below the poverty threshold, reflecting broad social of factors, including population pressures and poverty. The inequity and other social challenges. result: Public health, well-being and sustainable develop- This wallchart provides information and data on crit- ment are at risk. Cities are becoming more crowded and ical population, health, and environmental issues in the polluted, and the reliability of food and water supplies is Philippines. Examining these data, understanding their more uncertain than a generation ago. The productivity of interactions, and designing strategies that take into the country’s agricultural lands and fisheries is declining account these relationships can help to improve people’s as these areas become increasingly degraded and pushed lives while preserving the natural resource base that pro- beyond their production capacity. Plant and animal species vides for their livelihood and health. Population Reference Bureau 1875 Connecticut Ave., NW, Suite 520 Washington, DC 20009 USA Mangroves Help Sustain Human Vulnerability Coastal Communities to Natural Hazards Comprising more than 7,000 islands, the Philippines has an extensive coastline that is a is Increasing critical environmental and economic resource for the nation.