1 Industrial Court of Malaysia Case No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-University Programme, Students Can Volunteer for Internships with Accredited Partners and Learn FUTURE READY Backing Them up Every Step of the Way

YOUR FUTURE BUILT TODAY 6 30+ 16,500+ campuses across years of students currently Malaysia empowering served young minds 1,000+ 70,000+ employees graduates whose nationwide lives we have touched ABOUT INTI At INTI, our mission is to bridge the needs of tomorrow through the competencies our students gain today, empowering them to become the leaders, innovators and game changers of the future. We are committed towards ensuring our students gain the competencies needed for the workplace of the future, and to work alongside the digital transformations driving today’s global businesses in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Through our innovative teaching and learning and extensive industry partnerships, we empower our students with the ability to work with smart machines, to process and analyse data for better decision-making, to learn about technologies that impact businesses and manufacturing processes, and to develop professional skills such as adaptability, working with multidisciplinary teams, problem-solving, and a thirst for lifelong learning. By inspiring our students to explore their passions and discover their true potential through the right skills, tools and experiences, we continue to be a force of change in revolutionising education. Our commitment is to ensure exceptional graduate outcomes, and to transform our students into the dynamic leaders of the future – ones who will lead us in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, and beyond. Awarded FIVE STARS in the QS STARS RATING, achieving top marks in the categories of Online Learning, -

Legal Update 4Th Quarter 2005

EST 1918 SSSHOOK LLLIN k BBBOK KUALA LUMPUR EST 1918 SHOOK Lin k BOK KUALA LUMPUR LEGAL UPDATE Vol 1 No 4 PP13906/8/2006 4th Quarter 2005 The partners of the firm recently had a rare group photo call opportunity. Above are the General Partners (Executive Committee) of the firm. The partners take this opportunity to extend to our readers wishes for a happy and splendid new year ahead. Front (left to right): Dato’ Cyrus Das (Deputy Chief Executive Partner), Too Hing Yeap (Chief Executive Partner), Porres Royan. Rear (left to right): Lai Wing Yong, Michael Soo, Romesh Abraham, Jal Othman, Nagarajah Muttiah, Patricia David. IN THIS ISSUE CASE UPDATES INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ........................ 9 BANKING ........................ 5 LAND .............................. 9 CONTRACT ...................... 6 INTELLECTUAL DEFAMATION ................... 7 PROPERTY NEWS ............ 11 EMPLOYMENT ................. 8 4th Quarter 2005 1 EST 1918 SSSHOOK LLLIN k BBBOK KUALA LUMPUR Front (left to right): Patricia David, Lai Wing Yong, Dato’ Cyrus Das (Deputy Chief Executive Partner), Too Hing Yeap, (Chief Executive Partner), Porres Royan, Romesh Abraham, Mohan Kanagasabai. Rear (left to right): Chay Ai Lin, Khong Mei Lin, Yoong Sin Min, Yuen Kit Lee, Jal Othman, Michael Soo, Steven Thiru, Dahlia Lee, Chan Kok Keong, Ivan Ho, Lam Ko Luen, Nagarajah Muttiah, Adrian Hii, Hoh Kiat Ching, Goh Siu Lin, Tharmy Ramalingam. Absent: Sudharsanan Thillainathan 2 4th Quarter 2005 EST 1918 SSSHOOK LLLIN k BBBOK KUALA LUMPUR The above are all the general and limited partners of the firm. 4th Quarter 2005 3 EST 1918 SSSHOOK LLLIN k BBBOK KUALA LUMPUR 4 4th Quarter 2005 EST 1918 SSSHOOK LLLIN k BBBOK KUALA LUMPUR Case Updates That issue should be considered on another occasion. -

Tuesday 23 October 2012 at 9.30 Am PLACE: Room 310, L

NOTICE OF MEETING: ACADEMIC STANDARDS AND QUALITY COMMITTEE DATE AND TIME: Tuesday 23 October 2012 at 9.30 am PLACE: Room 310, Lincoln Student Services Building D Anderson REGISTRAR 14 October 2012 A G E N D A 1. MINUTES OF MEETING HELD ON 18 SEPTEMBER 2012 The minutes of the meeting held on 18 September 2012 are attached (Attachment 1). FOR APPROVAL 2. BUSINESS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES 2.1 Report to Academic Senate Academic Senate at its meeting on 2 October 2012 approved the recommendations of the ASQC meeting held on 18 September 2012. FOR NOTING 3. INDIVIDUAL STUDENT CASES 3.1 Faculty Reports Individual Case Reports have been received from the Faculty of Arts and Faculty of Human Sciences. (Attachment 2) FOR NOTING 3.2 Student Appeal (s/n 41487818) An appeal against a Faculty decision has been received. Chair will report. 3.3 Student Appeal (s/n 41970004) An appeal against a Faculty decision has been received. Chair will report. FOR DISCUSSION S:\APS\ASQC\Agenda\2012\10 - 23_Oct\Agenda 23 Oct 2012.docx 4. REPORT OF THE UNDERGRADUATE SUB-COMMITTEE The Undergraduate Sub-Committee met on 9 and 16 October 2012. The agenda and associated papers for the Sub-Committee’s meetings can be found for review by members on the ASQC web site at: http://senate.mq.edu.au/apc/sub_committees.html The report of the Sub-Committee’s meetings will be tabled. FOR DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATION TO ACADEMIC SENATE 5. REPORT OF THE POSTGRADUATE SUB-COMMITTEE The Postgraduate Sub-Committee met on 11 October 2012. -

Curriculum Vitae

C URRICULUM V ITAE DR. CHOW OW WEI Department of Music, Faculty of Human Ecology, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 UPM Serdang, Selangor, MALAYSIA [email protected] +603 8946 7131/ 7120 https://upm.academia.edu/owchow https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Owwei_Chow Google Scholar: Chow Ow Wei R ESEARCH I NTERESTS Cultural Musicology Virtual Ethnography Visual Anthropology in related disciplines of culture, ethnomusicology, urban music, popular music, folk music, traditional music, religious music, world music, popular culture, Buddhist music, Buddhist philosophy, phemonenality, virtuality, internet of things, online media, digital culture, digital activism, censorship, ethics in audiovisual media, audiovisual ethnography, film, film music, parody, interdisciplinarity, digital archive, institutional repository, qualitative research methods, phenomenology, hermaneutics E DUCATION 2016 Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in Music UNIVERSITI PUTRA MALAYSIA Serdang 2009 Master of Science (M.Sc.) in Music UNIVERSITI PUTRA MALAYSIA Serdang 1998 Bachelor of Science (BSc.) (Hons) UNIVERSITI MALAYSIA SARAWAK Kota Samarahan M AJOR A PPOINTMENTS & A CCOMPLISHMENTS 2018– Senior Lecturer UNIVERSITI PUTRA MALAYSIA Serdang 1 2018– Member of Editorial Board ASIA-EUROPE MUSICAL RESEARCH JOURNAL Asia-Europe Musical and Cultural Research Centre, Shanghai Conservatory of Music, Shanghai 2018– Part-time Lecturer XIAMEN UNIVERSITY MALAYSIA Salak Tinggi 2017 Part-time Lecturer 2012 – 2013 UNIVERSITI PUTRA MALAYSIA Serdang 2012– 2013 Columnist GUANG MING DAILY -

IMONST 1 2020 RESULTS (Updated 26 September 2020)

IMONST 1 2020 RESULTS (Updated 26 September 2020) NOTES ON THE RESULTS • The results show all the Medal winners in IMONST 1. • All medalists qualify for IMONST 2 as long as they fulfill the IMO criteria (must be a Malaysian citizen, and currently studying at pre-university level). • The cutoff to qualify for IMONST 2 is 80% or 40/50 in IMONST 1, for all categories. Around 330 students qualify for IMONST 2 this year. • The complete results for all participants (statistics, score report and certificates) will be available on the ContestHub system starting from 5 October 2020. • The score for each participant is counted as the higher between the score taken on 5 September, and the score taken on 12-14 September. • If there is any error, please write to [email protected] . • The result is final. TO THOSE WHO QUALIFY FOR IMONST 2 (INCLUDING ALL MEDALISTS), PLEASE GO TO https://imo-malaysia.org/imonst-2/ FOR DETAILS ON IMONST 2. THE PAGE WILL BE UPDATED BY 29 SEPTEMBER 2020. Award Cutoff for IMONST 2020 (all categories): AWARD POINTS Gold 50 Silver 45 – 49 Bronze 40 – 44 Tip: To find your name or school, use the “Find” function on your PDF reader (usually Ctrl+F). CONGRATULATIONS TO ALL WINNERS! PRIMARY AWARD NAME SCHOOL GOLD THANEISH HANZ PUTTAGUNTA INSPIROS INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL GOLD ONG YONG XIANG SJKC BUKIT SIPUT GOLD PHANG YI YANG SJKC CHERN HWA GOLD HAZE SHAH SJKC CHONG WEN GOLD IVAN CHAN GUAN YU SJKC CHUNG HUA BINTULU GOLD JOASH LIM HEN YI SJKC GUONG ANN GOLD CHAI FENG ZE SJKC JALAN DAVIDSON GOLD HOO XINYI SJKC JALAN DAVIDSON GOLD -

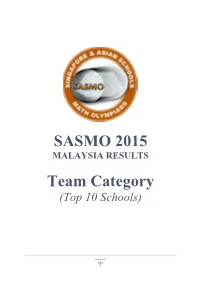

SASMO 2015 Team Category

SASMO 2015 MALAYSIA RESULTS Team Category (Top 10 Schools) P a g e | 1 YEAR 2 1. SJK (C) CHUNG KWOK, Jalan Merpati, Kuala Lumpur 2. SJK (C) HAN CHIANG, Georgetown, Pulau Pinang 3. SJK (C) PANDAN, Johor Bahru, Johor 4. SJK (C) FOON YEW 5, Johor Bahru, Johor 5. SJK (C) YUK CHIN, Tawau, Sabah 6. SJK (C) PUI GIN, Sandakan, Sabah 7. SJK (C) KAI CHEE, Butterworth, Penang 8. NOBEL INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL, Petaling Jaya, Selangor 9. SK BUKIT JELUTONG. Shah Alam, Selangor 10. SK SAUJANA IMPIAN, Kajang, Selangor SASMO 2015 Malaysia Results - Team Category (Top 10 Schools) P a g e | 2 YEAR 3 1. BRAINBUILDER - DR FONG SINGAPORE MATHS, Subang Jaya, Selangor 2. SJK (C) JALAN DAVIDSON, Jalan Hang Jebat, Kuala Lumpur 3. SJK (C) FOON YEW 5, Johor Bahru, Johor 4. SJK (C) KWANG HWA SG NIBONG, Pulau Pinang 5. SJK (C) HAN CHIANG, Georgetown, Pulau Pinang 6. SJK (C) KAI CHEE, Butterworth, Pulau Pinang 7. SK BANDAR UDA 2, Johor Bahru, Johor 8. SJK (C) KUEN CHENG 1, Jalan Belfield, Kuala Lumpur 9. NOBEL INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL, Petaling Jaya, Selangor 10. SJK (C) PUI GIN, Sandakan, Sabah SASMO 2015 Malaysia Results - Team Category (Top 10 Schools) P a g e | 3 YEAR 4 1. BRAINBUILDER - DR FONG SINGAPORE MATHS Subang Jaya, Selangor 2. SJK (C) JALAN DAVIDSON, Jalan Hang Jebat, Kuala Lumpur 3. SJK (C) KWANG HWA SG NIBONG, Pulau Pinang 4. SJK (C) HAN CHIANG, Georgetown, Pulau Pinang 5. SJK (C) FOON YEW 5, Johor Bahru, Johor 6. SJK (C) PANDAN, Johor Bahru, Johor 7. -

The Chinese Education Movement in Malaysia

INSTITUTIONS AND SOCIAL MOBILIZATION: THE CHINESE EDUCATION MOVEMENT IN MALAYSIA ANG MING CHEE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2011 i 2011 ANG MING CHEE CHEE ANG MING SOCIAL MOBILIZATION:SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS AND THE CHINESE EDUCATION CHINESE MOVEMENT INTHE MALAYSIA ii INSTITUTIONS AND SOCIAL MOBILIZATION: THE CHINESE EDUCATION MOVEMENT IN MALAYSIA ANG MING CHEE (MASTER OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, UPPSALA UNIVERSITET, SWEDEN) (BACHELOR OF COMMUNICATION (HONOURS), UNIVERSITI SAINS MALAYSIA) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2011 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My utmost gratitude goes first and foremost to my supervisor, Associate Professor Jamie Seth Davidson, for his enduring support that has helped me overcome many challenges during my candidacy. His critical supervision and brilliant suggestions have helped me to mature in my academic thinking and writing skills. Most importantly, his understanding of my medical condition and readiness to lend a hand warmed my heart beyond words. I also thank my thesis committee members, Associate Professor Hussin Mutalib and Associate Professor Goh Beng Lan for their valuable feedback on my thesis drafts. I would like to thank the National University of Singapore for providing the research scholarship that enabled me to concentrate on my thesis as a full-time doctorate student in the past four years. In particular, I would also like to thank the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences for partially supporting my fieldwork expenses and the Faculty Research Cluster for allocating the precious working space. My appreciation also goes to members of my department, especially the administrative staff, for their patience and attentive assistance in facilitating various secretarial works. -

Pg. 3-4 Koh: Traffic & Housing Problem Increase Burden Penangites

PP 16376/08/2012 (030849) January - March 2013 pg. 3-4 Koh: Traffic & housing problem increase burden Penangites pg. 5 Politics is a long-term struggle, Gerakan will never dissolve pg. 20 Gerakan cares for the people and hopeful for the future www.gerakan.org.my for internal circulation only | 只供内部传阅 GM_2013_02JanMar_v4.indd 1 3/29/2013 3:41:50 PM Contents 3 & 4 Koh: Traffic & housing problem increase burden Penangites EDITORIAL BOARD 编辑部 槟交通房屋问题增市民负担 §À¡ìÌÅÃòÐ ÁüÚõ Å£¼¨ÁôÒ À¢Ã¨É ÌÊÁì¸Ç¢ý Publicity, Information & Communication Chairman ͨÁ¨Â «¾¢¸Ã¢ì¸¢ÈÐ 宣传、资讯及通讯局主任 - Teng Chang Yeow 邓章耀 5 政治是长远斗争 民政党绝不解散 Politics is a long-term struggle, Gerakan will never dissolve Editor-in-Chief 总编辑 陈全坤 - Tan Chuan Koon 6 Mah urges more self employed people to participate in the 1 Malaysia Retirement Saving Scheme Editor 编辑 马袖强冀自雇人士踊跃参与退休储蓄计划 - Lim Shi Hou 林诗豪 Teng questions the need for undersea tunnel in Penang Sub-Editors 助编 7 - Lee Chun Hung 李俊鸿 邓章耀质问槟城建海底隧道的需要 - Tan Aik Mund 陈毅民 8 Abort Tunnel Vision - S.M. Mohamed Idris, CAP President Layout & Design 美术编辑 槟岛承受力有限不应引进更多车 - Lim Shi Hou 林诗豪 槟消协促取消海底隧道工程 许子根移交首相拨款 隆4独中再获100万令吉 Address: Level 5, Tower 1, Menara PGRM, 9 No. 6 & 8, Jalan Pudu Ulu, Gerakan presented federal aid to Sabah communities 56100 Cheras, Kuala Lumpur Tel: 03-9287 6868 10, 11 & 12 The Legacy of A True Malaysian - Fax: 03-9287 8866 Tun Dr. Lim Keng Yaik memorial service Website: www.gerakan.org.my Ðý ¼¡ì¼÷ Ä¢õ ¦¸í ±ö츢ý ¿¢¨É× ²ó¾ø ¿¢¸ú× - ´Õ ¯ñ¨ÁÂ¡É Á§Äº¢Ââý Gerakan matters! would like to invite members to send «¨¼Â¡Çî ÍÅÎ in your views. -

DESIRE and SELFHOOD GLOBAL CHINESE RELIGIOUS HEALING in PENANG, MALAYSIA a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Gradua

DESIRE AND SELFHOOD GLOBAL CHINESE RELIGIOUS HEALING IN PENANG, MALAYSIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by I-Fan Wu December 2018 © 2018 I-Fan Wu DESIRE AND SELFHOOD GLOBAL CHINESE RELIGIOUS HEALING IN PENANG, MALAYSIA I-Fan Wu, Ph. D. Cornell University 2018 This dissertation is an ethnographic examination of Chinese meditators who, propelled by their suffering, pursue alternative religious healing education to harmonize their conflicts with social others and to answer their existential questions. Using Lacan’s analysis of desire as an analytic with which to understand two religious healing schools—Bodhi Heart Sanctuary in Penang with global lecturers, and Wise Qigong centers in Penang, Hong Kong, and Shenzhen—this dissertation delineates and explains how, in the Chinese diaspora, unconscious desires are expressed through alternative religious healing systems. The doctrines of Bodhi Heart Sanctuary and Wise Qigong follow a similar internal logic: they teach their disciples to submit themselves to a new alterity that resembles Confucianism, requiring self-submission if not asceticism. In so doing, practitioners, misrecognizing the source of their self-making, claim to transcend their suffering by overcoming their desires with the guidance of the new alterity, which represents a new form of ego-ideal. By attaching themselves to the best object—Buddha’s Right View, or hunyuan qi, the “primordial energy”—practitioners believe that they revitalize themselves as they address and work through the existential dilemmas involved in everyday interactions. This dissertation explicates the process through which Chinese forms of “self-help” therapy make sense to people as a manifestation of cross-cultural human existential concerns while these concerns take distinctively Chinese forms. -

Firm Profile

OUR MISSION STATEMENT We strive for total value management by creating value for all stakeholders: - Clients, Team Members, Associates and Partners. We believe that our Client is the driving force behind our practice. Our Client philosophy is advice-led and “Kam Cheng” value is always at the heart of our relationships. We are committed to train and build our Team Members in augmenting their skills and expertise. Our Team Members are our valued asset and they are empowered to go the “extra mile” to secure the best interests of our Client. At our core, we are a law firm with an over-riding commitment to the highest quality of research, advice and solutions expected by our Client. We embrace the age of Information Technology and will continuously invest in appropriate technology to add value to our legal services. We are committed to uplift the social well-being of our community and to preserve the environment by providing the necessary resources and advice. MESSRS CHEE SIAH LE KEE & PARTNERS No. 2B Jalan KLJ 4, Taman Kota Laksamana Jaya 75200 Melaka Malaysia We are a partnership firm of nine partners practising at No. 2B Jalan KLJ 4, Taman Kota Laksamana Jaya, 75200 Melaka and we are assisted by one senior associate, four associates and one consultant, totalling fifteen lawyers. HISTORY OF THE FIRM Dato’ Chee Kong Chi started the firm on 18th January 1981 with one clerk. Over the years with the support of loyal clients and staff, the firm has grown to its present size of fifteen (15) lawyers and forty five (45) team members. -

Decentworkcheck.Org

Malaysia DECENTWORKCHECK.ORG National Regulation exists Check DecentWorkCheck Malaysia is a product of WageIndicator.org and www.gajimu.my/utama National Regulation does not exist 01/13 Work & Wages NR Yes No 1. I earn at least the minimum wage announced by the Government 2. I get my pay on a regular basis. (daily, weekly, fortnightly, monthly) 02/13 Compensation 3. Whenever I work overtime, I always get compensation ȋƤȌ 4. Whenever I work at night, I get higher compensation for night work 5. I get compensatory holiday when I have to work on a public holiday or weekly rest day 6. Whenever I work on a weekly rest day or public holiday, I get due compensation for it 03/13 Annual Leave & Holidays 7. How many weeks of paid annual leave are you entitled to?* 1 3 2 4+ 8. I get paid during public (national and religious) holidays 9. I get a weekly rest period of at least one day (i.e. 24 hours) in a week 04/13 Employment Security 10. I was provided a written statement of particulars at the start of my employment 11. Dzdz 12. My probation period is only 06 months 13. My employer gives due notice before terminating my employment contract (or pays in lieu of notice) 14. ơ Ǥ 05/13 Family Responsibilities 15. My employer provides paid paternity leave Ȁ 16. My employer provides (paid or unpaid) parental leave Ǥ Ǥ 17. ƪ Ǧƪ 06/13 Maternity & Work 18. I get free ante and post natal medical care 19. ǡ ȋȌ 20. -

Closing Ceremony

100 Team 423 - Kaisei Academy, Tokyo Kenji Steiner School, Choate Rosemary Hall - Yukoh Shimizu, Miles Hirozumi Shiotsu, Aiyu Kamate 99 Team 570 - Villa International High School - Ibrahim Mikyaal Ahmed, Aishath Zeyba Atho, Adam Navee Mohamed 98 Team 325 - King George V School - Brandon Choy, Brandon Tong, Arthur Cheung 97 Team 639 - II Gimnazija Maribor - Helena Godina, Barbara Simonič, Jure Kekec 96 Team 397 - Ahad Haam High School - Nicole Grossman, Roey Shemesh, Iddo Beker 95 Team 414 - Doshisha International Junior and Senior High School, Redmond High School - Toko Narita, Yukina Yamaguchi, Ayaka Takei 94 Team 450 - Nishiyamato Gakuen High School - Shiyu Yoshikawa, Amiri Hirayama, Yuki Otake 93 Team 256 - International High School Affiliated to SCNU - Ruijun Sun, Yantang Du, Siqi Wang 92 Team 731 - Shanghai United International School Gubei - Roslyn Hong, Yeguo Ye, Katherine Wang 91 Team 386 - Sekolah Victory Plus - Clara Inggrid Rouli Tambunan, Russell Revel Wijanto, Jovita Nakeisha Venska 90 Team 218 - British School of Bahrain - Rose Baslious Salib, Kaviesh Ramesh Kinger, Syed Yousaf Kamran Zain 89 Team 558 - St Joseph’s Institution International Malaysia - Kyra Chellam, Meagan Motha, Carmen Foo 88 Team 299 - Wellington College International Shanghai - Jung Chi George Chang, Han Sheng Nicholas Su, Leopold Lind 87 Team 742 - Macleans College - Nancy Chen, Regina Yun, Sue Jynn Leong 86 Team 344 - Heritage School Rohini - Divyanshi Agarwal, Shubhi Agarwala, Avni Jain 85 Team 541 - Kolej PERMATApintar - Ruehan Thiagarajan, Akif Irfan