RAJMAHAL: a MEDIEVAL TOWN in SUBAH BENGAL ' Varun Kumar Roy1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medieval Banaras: a City of Cultural and Economic Dynamics and Response

[VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 4 I OCT. – DEC. 2018] e ISSN 2348 –1269, Print ISSN 2349-5138 http://ijrar.com/ Cosmos Impact Factor 4.236 Medieval Banaras: A City of Cultural and Economic Dynamics and Response Pritam Kumar Gupta Research Scholar, Jawaharlal Nehru University. Received: November 12, 2018 Accepted: December 17, 2018 ABSTRACT This paper attempts to understand the cultural and economic importance of the city of Banarasto various medieval political powers.As there are many examples on the basis of which it can be said that the nature, dynamics, and popularity of a city have changed at different times according to the demands and needs of the time. Banaras is one of those ancient cities which has been associated with various religious beliefs and cultures since ancient times but the city, while retaining its old features, established itself as a developed trade city by accepting new economic challenges, how the Banaras provided a suitable environment to the changing cultural and economic challenges, whereas it went through the pressure of different political powers from time to time and made them realize its importance. This paper attempts to understand those suitable environmentson how the landscape of Banaras and its dynamics in the medieval period transformed this city into a developed economic-cultural city. Keywords: Banaras, Religious, Economic, Urbanization, Mughal, Market, Landscape. Wide-ranging literary works have been written on Banaras by scholars of various subject backgrounds, in which they highlight the socio-economic life of different religious and cultural ideals of the inhabitants of Banaras. It is very important for scholars studying regional history to understand what challenges a city has to face in different historical periods to maintain its identity.The name Banaras is found as the present name Varanasi in the Buddhist Jataka and Hindu epic Mahabharata. -

The Core and the Periphery: a Contribution to the Debate on the Eighteenth Century Author(S): Z

Social Scientist The Core and the Periphery: A Contribution to the Debate on the Eighteenth Century Author(s): Z. U. Malik Source: Social Scientist, Vol. 18, No. 11/12 (Nov. - Dec., 1990), pp. 3-35 Published by: Social Scientist Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3517149 Accessed: 03-04-2020 15:29 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Social Scientist is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social Scientist This content downloaded from 117.240.50.232 on Fri, 03 Apr 2020 15:29:21 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Z.U. MALIK* The Core and the Periphery: A Contribution to the Debate on the Eighteenth Century** There is a general unanimity among modern historians on seeing the dissolution of Mughal empire as a notable phenomenon cf the eighteenth century. The discord of views relates to the classification and explanation of historical processes behind it, and also to the interpretation and articulation of its impact on political and socio- economic conditions of the country. Most historians sought to explain the imperial crisis from the angle of medieval society in general, relating it to the character and quality of people, and the roles of the diverse classes. -

Malda Division

MALDA DIVISION 0 MALDA DIVISION 1 DISCLAIMER The information provided in this document is for the purpose of general guidance. Although all efforts have been made to ensure that it is authentic and accurate, however, in case of any conflict, the GR & SR /Accident Manual and other Codes would override. 2 3 4 CONTENTS Chapter Subject Matter Page No. Maps – Malda Division System Map 3 Rail & Road Map 4 1. ASSISTANCE FROM DEFENCE ORGANISATION IN CASE OF 6 RAILWAY DISASTER Assistance for Helicopter from Defence during Major Railway Disaters. 7 National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) 8-11 2. Important Numbers of Head Quarter & all Divisions of ER 13 Telephone numbers of Way side station of Malda division Telephone Numbers of Services HQs and Corresponding Railway Zonal/Divisional HQ. 3. CUG Numbers of Malda Division CUG Numbers of DRM, Accounts, Commercial CUG Numbers of Engineering & Electrical Department CUG Numbers of Mechanical department CUG Numbers of Medical department CUG Numbers of Operating, Personnel & RRB department CUG Numbers of S & T department CUG Numbers of Safety, Security & Stores department Phone Numbers of Medical/SBG & JMP Civil officers and Police offices 4. Station-wise information regarding disaster-management plan of Malda Division MLDT-BDAG L/C section DGLE-MPLR section BHW-SLJ ( Incl. TPH-RJL) section SBG-SBO section BGP-RPUR ( Incl. BGP-MDLE) section JMP-DNRE section Station-wise information regarding disaster-management plan of Malda Division 5 MLDT-BDAG L/C section DGLE-MPLR section BHW-SLJ ( Incl. TPH-RJL) section SBG-SBO section BGP-RPUR ( Incl. BGP-MDLE) section JMP-DNRE section 5 Chapter-1 ASSISTANCE FROM DEFENCE ORGANISATION IN CASE OF RAILWAY DISASTER. -

Sahebganj Districts, Jharkhand

कᴂद्रीय भूमि जल बो셍ड जल संसाधन, नदी विकास और गंगा संरक्षण विभाग, जल शक्ति मंत्रालय भारत सरकार Central Ground Water Board Department of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation, Ministry of Jal Shakti Government of India AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT OF GROUND WATER RESOURCES SAHEBGANJ DISTRICTS, JHARKHAND राज्य एकक कायाालय, रांची State Unit Office, Ranchi भारत सरकार Government of India जऱ स車साधन, नदी विकास एि車 ग車गा स車रक्षण म車त्राऱय Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation केन्द्रीय भमू म-जऱ र्बो셍ा Central Ground Water Board PART – I/ भाग -१ Aquifer Maps and Ground Water Management Plan of Sahebganj district, Jharkhand जऱभतृ न啍शे तथा भूजऱ प्रबंधन योजना साहिबगंज जजऱा, झारख赍ड State Unit Office, Ranchi Mid-Eastern Region, Patna March 2019 रा煍य एकक कायााऱय रा車ची मध्य-ऩर्बू ी क्षेत्र ऩटना माचा २०१९ Aquifer Maps and Ground Water Management Plan of Sahebganj district, Jharkhand जऱभतृ न啍शे तथा भूजऱ प्रबंधन योजना साहिबगंज जजऱा, झारख赍ड State Unit Office, Ranchi Mid-Eastern Region, Patna March 2019 रा煍य एकक कायााऱय रा車ची मध्य-ऩर्बू ी क्षेत्र ऩटना माचा २०१९ REPORT ON AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT PLAN (PART – I) OF SAHEBGANJ DISTRICT, JHARKHAND 2017 – 18 CONTRIBUTORS’ Principal Authors Sunil Toppo : Junior Hydrogeologist (Scientist-B) Supervision & Guidance A.K.Agrawal : Regional Director G. K. Roy : Officer-In- Charge T.B.N. Singh : Scientist-D Dr Sudhanshu Shekhar : Scientist-D Hydrogeology, GIS maps and Management Plan Sunil Toppo : Junior Hydrogeologist Dr Anukaran Kujur : Assistant Hydrogeologist Atul Beck : Assistant Hydrogeologist Hydrogeological Data Acquisition and Groundwater Exploration Sunil Toppo : Junior Hydrogeologist Dr Anukaran Kujur : Assistant Hydrogeologist Atul Beck : Assistant Hydrogeologist Geophysics : B. -

Central Administration of Akbar

Central Administration of Akbar The mughal rule is distinguished by the establishment of a stable government and other social and cultural activities. The arts of life flourished. It was an age of profound change, seemingly not very apparent on the surface but it definitely shaped and molded the socio economic life of our country. Since Akbar was anxious to evolve a national culture and a national outlook, he encouraged and initiated policies in religious, political and cultural spheres which were calculated to broaden the outlook of his contemporaries and infuse in them the consciousness of belonging to one culture. Akbar prided himself unjustly upon being the author of most of his measures by saying that he was grateful to God that he had found no capable minister, otherwise people would have given the minister the credit for the emperor’s measures, yet there is ample evidence to show that Akbar benefited greatly from the council of able administrators.1 He conceded that a monarch should not himself undertake duties that may be performed by his subjects, he did not do to this for reasons of administrative efficiency, but because “the errors of others it is his part to remedy, but his own lapses, who may correct ?2 The Mughal’s were able to create the such position and functions of the emperor in the popular mind, an image which stands out clearly not only in historical and either literature of the period but also in folklore which exists even today in form of popular stories narrated in the villages of the areas that constituted the Mughal’s vast dominions when his power had not declined .The emperor was looked upon as the father of people whose function it was to protect the weak and average the persecuted. -

![Ftyk Fuokzpu Dk;Kzy;] Lkgscxat](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2720/ftyk-fuokzpu-dk-kzy-lkgscxat-1372720.webp)

Ftyk Fuokzpu Dk;Kzy;] Lkgscxat

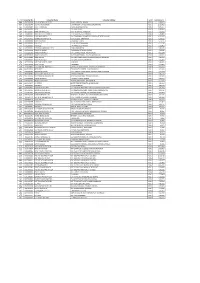

ftyk fuokZpu dk;kZy;] lkgscxat ch0,y0vks0 dh lwph 01& jktegy fo/kku lHkk fuokZpu {ks= AC- Booth Booth Name Name of BLO Mobile No Address NO Number Middle School Hajipur Diyara 1-Vill- Hajipur Diyara, Dist- 1 1 Savita Devi 9939967486 (New Building) Sahibganj Middle School Hajipur Diyara, 2-Vill- Hajipur Diyara, Dist- 1 2 Sangita Devi 9955137519 (Old Building) Sahibganj Middle School Hajipur Diyara, 3-Vill- Hajipur Diyara, Dist- 1 3 Sulekha Devi 7739650069 (Old Building) Sahibganj 4-Vill- Hajipur Bhitta, Dist- 1 4 Up. Middle School, Rajgaown Ramakanta Devi 8936016787 Sahibganj 5-Vill- Hajipur Bhitta, Dist- 1 5 Up. Middle School, Rajgaown Babita Devi 9973195910 Sahibganj 1 6 Panchayat Building, Dihari Manju Kumari 9973195910 6-Vill- Dihari, Dist- Sahibganj 1 7 Up.High School,, Dihari Ajay Kumar Yadav 7766017485 7-Vill- Dihari, Dist- Sahibganj Up. Middle School, Patwar 8-Vill- Patwar Tola, Dist- 1 8 Rita Devi 9801340228 Tola Sahibganj Up. Middle School, Patwar 1 9 Usha Devi 9661205005 9-Vill- Dihari, Dist- Sahibganj Tola Up. Middle School Badi 10-Vill-Bholiya Tola, Dist- 1 10 Shavya Devi 8409462362 Kodarjanna Sahibganj Middle School Badi 11-Vill-Bari Kojarjanna South, 1 11 Renu Devi 9006958107 Kodarjanna (South Part) Dist- Sahibganj Middle School Badi 12-Vill-Mahaldar Tola, Dist- 1 12 Shrimani Devi 8271720579 Kodarjanna (North Part) Sahibganj Middle School Badi 13-Vill- Naya Tola, Dist- 1 13 Kiran Devi 9771823375 Kodarjanna (North Part) Sahibganj Urdu Middle School 14-Vill- Makhmalpur South, 1 14 Akhtari Begam 9801430040 Makhmalpur Dist- Sahibganj Panchayat Building 15-Vill-Rahamat Tola, Dist- 1 15 Anjuman Aara 7295915866 Makhmalpur ( South Part) Sahibganj Panchayat Building 16-Vill- Sarpanch Tola, Dist- 1 16 Alimuddin Jang 9798190712 Makhmalpur ( South Part) Sahibganj Up. -

ATDC -16-17.Xlsx

List of Skilled Candidates for Skill Development Training Programme on Sewing Machine Operator (B+ A) Sponsored By NSFDC in Session 2016-17 ( From 15.09.16 to 14.12.16 ) Address Status of Training Stipend Name of the Annual S.no Father's Name Category Area Disbursement Candidate Income Amount DELHI B-423,Gali no-3 Meet Nager,Gokalpuri,Delhi-110094 1 Rekha Rani Sri Ram SC Urban 72000/- 3000 Completed B-118,G.no-3,Saboli Khadda,Delhi-110093 2 Priyanka Jagdish SC Urban 48000/- 3000 Completed H.no-739,G.no-13 Mandoli Vistar,nand nagri Delhi-110093 3 Pushpa Panna Lal SC Urban 60000/- 3000 Completed H.no-E61-A247,D2 Block Jhuggi Nand Nagri Delhi-110093 4 Vandana Ramnath SC Urban 35000/- 4500 Completed E-56-22,G.T.Road Village Khera Delhi- 110095 5 Suman Heera Lal SC Rural 60000/- 4500 Completed H.no-13-737,Mandoli Vistar Mondoli Delhi-110093 6 Komal Satya Pal SC Urban 60000/- 3000 Completed B-3-197 Nand Nagri Delhi 110093 7 Gayatri Panna Lal SC Urban 48000/- 1500 Completed C-2-330,G.no-12 Harsh Vihar Delhi 110093 8 Jai Bharti Mitter Singh SC Urban 48000/- 1500 Completed D-2-287,Nand Nagri,Mondoli Delhi- 110093 9 Priyanka Kumari Bajrangi SC Urban 72000/- 1500 Completed E-60-400 Jhuggi,Sunder Nagri Delhi- 110093 10 Ragini Ashok SC Urban 25000/- 3000 Completed H.no-28,G.no-2,Mandoli Village Delhi- 110093 11 Jyoti Santer Pal SC Urban 60000/- 3000 Completed E-18-602,G.no-18 Amar Colony Gokal Pur Delhi110094 12 Laxmi Pooja Devender Singh SC Urban 80000/- 3000 Completed H.no-105,D.D.A Janta Flats G.T.B Enclave Dilshad Garden 13 Meena Kumari Ram Awadh -

List of Consumers of Sahibganj

SL. NO Consumer No. Consumer Name Consumer Address Tarrif Total Amount 298 GVCS000006 THE I/C MEDICAL OFFICER RANGA HOSPITAL, RANGA NDS-3 11,58,453 397 GVCS000046 DISTRICT HOMEGAURD COMMANDENT OFFICE, BANSKOLA,SAKRIGALI NDS-3 10,96,411 396 GVCS000029 B.D.O. , RAJMAHAL , NAYA BAZAR,RAJMAHAL NDS-3 10,90,657 395 GVCS000030 B D O , TALJHARI BLOCK NDS-3 10,88,846 297 MJPCS00557 BHARTI INFRATEL LTD PROP- A DWIVEDI, MIRZAPUR NDS-3 7,91,505 392 TPCS000005 DIVN.ELEC.EXEC.ENGINEER , E.RLY,MALDA,AT-TEENPAHAR NDS-3 6,98,808 198 LHDCS00001 SUNIL KR BHARTIYA S/o LT MURARILAL BHARTIYA, LOHANDA,AT-PETROL PUMP NDS-3 6,81,282 296 BHCS002471 ADIWASI KALYAN HOSTEL B S K COLLEGE, BARHARWA NDS-3 6,14,929 386 GVCS000002 SUPDT OF POLICE , RAJMAHAL THANA NDS-3 6,11,735 385 GVCS000033 CIVIL S.D.O. , S.D.O. COURT,RAJMAHAL NDS-3 6,11,126 295 GVCS000015 THE B.D.O. , PATHNA BLOCK,PATHNA NDS-3 5,93,452 294 GVCS000014 THE PRAKHAND BIKASH OFFI. , BARHARWA BLOCK NDS-3 5,90,543 380 GVCS000004 THANA INCHARGE , RADHANAGAR THANA,UDHWA NDS-3 5,14,026 191 MZCCS00783 BRANCH MANAGER STATE BANK OF INDIA, MIRZA CHAUKI NDS-3 4,79,984 190 MDSCS00045 BRANCH MANAGER STATE BANK OF INDIA, CHHOTA MADANSAHI NDS-3 4,63,921 188 BROCS00546 HEAD MASTER STR GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL, BANDARKOLA,BORIO,SAHIBGAN NDS-3 4,56,278 377 GVCS000007 MEDICAL OFFICER , REFERAL HOSPITAL,RAJMAHAL NDS-3 4,32,801 179 GVCS000009 DIST EMPLOYMENT OFFICE , LOHANDA NDS-3 3,98,842 373 GVCS000001 SUPDT OF JAIL , RAJMAHAL NDS-3 3,75,802 369 RJLCS01800 ATC TOWER OF INDIA (P) LT C/o MD ZIAUDDIN AHMED, GUDRAGHAT,RAJMAHAL NDS-3 -

Temple Destruction and the Great Mughals' Religious

Analisa Journal of Social Science and Religion Website Journal : http://blasemarang.kemenag.go.id/journal/index.php/analisa DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18784/analisa.v3i1.595 TEMPLE DESTRUCTION AND THE GREAT MUGHALS’ RELIGIOUS POLICY IN NORTH INDIA: A Case Study of Banaras Region, 1526-1707 Parvez Alam Department of History, ABSTRACT Banaras Hindu University, Banaras also known as Varanasi (at present a district of Uttar Pradesh state, India) Varanasi, India, 221005 [email protected] was a sarkar (district) under Allahabad Subah (province) during the great Mughals period (1526-1707). The great Mughals have immortal position for their contribu- Paper received: 07 February 2018 tions to Indian economic, society and culture, most important in the development of Paper revised: 15 – 23 May 2018 Ganga-Jamuni Tehzeeb (Hindustani culture). With the establishment of their state in Paper approved: 11 July 2018 Northern India, Mughal emperors had effected changes by their policies. One of them was their religious policy which is a very controversial topic though is very impor- tant to the history of medieval India. There are debates among the historians about it. According to one group, Mughals’ religious policy was very intolerance towards non- Muslims and their holy places, while the opposite group does not agree with it, and say that Mughlas adopted a liberal religious policy which was in favour of non-Mus- lims and their deities. In the context of Banaras we see the second view. As far as the destruction of temples is concerned was not the result of Mughals’ bigotry, but due to the contemporary political and social circumstances. -

CAN the REIGN of SHAH JAHAN BE CALLED the GOLDEN ERA of INDIAN HISTORY? *Mr

C S CAN THE REIGN OF SHAH JAHAN BE CALLED THE GOLDEN ERA OF INDIAN HISTORY? *Mr. Ashutosh Audichya & **Dr. Anshul Sharma **PhD Scholar, Himalayan University, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh, India. **Head & Assistant Professor, Department of History, S.S Jain Subodh .P.G College, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India. ABSTRACT: Emperor Shah Jahan was one of the greatest Mughal Emperors of India. He ruled an empire that was as vast as the Roman Empire and the British Empire. It covered today’s India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Nepal, Bhutan and parts of Iran. Shah Jahan during his reign built up a strong army that ensured that he ruled one of the largest empires in the history of the world. Mewar, which was a hostile kingdom for centuries submitted to Mughal dominance. It was during Shah Jahan’s time that the south Indian kingdoms like Ahmednagar, Bijapur and Golcoonda also submitted to the Mughal dominance. During this period some of the world’s most beautiful pieces of art and architecture were built up like the Red Fort of Delhi, the Taj Mahal of Agra, the famous peacock throne etc. Financial collections of the Empire rose to the highest level during this period. This was a phase of Indian history which was by and large peaceful and progressive. But in spite of this, this period has been painted in black by many historians. Extravagant lifestyle of the Emperor, huge expenses for promoting art and architecture, too much pressure exerted on subjects for payment of taxes, increasing corruption levels of the army and the royal executive were reasons that created a severe financial recession immediately after the reign of Shah Jahan ended. -

Environment Monitoring Plan of Sahibganj Terminal for Construction and Operation Phase

“CAPACITY AUGMENTATION OF NATIONAL WATERWAY.1” (Jal Marg Vikas Project) ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORTS VOLUME - 5: Environmental Management Plan (EMP) for Sahibganj Terminal May 2016 Consolidated Environmental Impact Assessment Report of National Waterways-1, Volume-5 Table of Contents 1.1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 3 1.2. Brief On Sahibganj Terminal ........................................................................................... 3 1.3. Description of Environment ............................................................................................. 4 1.4. Environmental Management and Monitoring Plan.......................................................... 8 1.5. Environment Health and Safety Cell ............................................................................... 9 1.6. Reporting Requirements: ................................................................................................ 9 List of Tables Table 1.1 : Salient Environmental Features of Sahibganj Terminal Site ............................................. 5 Table 1.2 : Environment Management Plan Sahibganj Terminal During Construction Phase ......... 10 Table 1.3 2 Consolidated Environmental Impact Assessment Report of National Waterways-1, Volume-5 Chapter 1. EMP FOR SAHIBGANJ TERMINAL 1.1. Introduction Inland waterways Authority of India (IWAI) has proposed to augment the navigation capacity of waterway NW-1 (Haldia to Allahabad) -

VIKAS RATHEE Department of History Central University of Punjab V.P.O

Rathee cv VIKAS RATHEE Department of History Central University of Punjab V.P.O. Ghudda, District Bathinda, Punjab, INDIA 151401 [email protected] APPOINTMENTS July 2019 – now Assistant Professor, Department of History, School of Social Sciences, Central University of Punjab Nov 2016 – July 2019 Assistant Professor of History, South and Central Asian Studies, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab Oct 2014-Sept 2016 PBC Post-doctoral Research Fellow, Harry S. Truman Institute for the Advancement of Peace, Hebrew University of Jerusalem March 2005-March 2006 Guest Lecturer, Dept of Germanic & Romance Studies, University of Delhi Aug 2001 – Jun 2002 Manager (Logistics) & Tour Guide, Aquaterra Adventures (Pvt.) Ltd, Delhi for river and mountain operations in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh. EDUCATION Jan 2007-Aug 2015 Department of History, The University of Arizona Ph.D. in History (Middle Eastern Caucus), for the thesis “Narratives of the 1658 War of Succession for the Mughal Throne, 1658-1707,”. Committee: Richard Eaton (Chair), Linda Darling, Allison Busch (Columbia University) and Brian Silverstein (Anthropology). Minor: World & Comparative History. 2002-2006 Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi, India . M.Phil. in History (CGPA: 7.69 on a scale of 9.0, first division) . Unpublished M.Phil. Dissertation: “Centre and the Region: Aspects of the Making of Mughal Rule in the Bengal Subah, 16th and 17th Centuries” (Advisor: Rajat Datta) . M.A. in History (specialisation - Medieval Indian History, CGPA: 6.56 on a scale of 9.0, First Division), Centre for Historical Studies, School of Social Sciences 1998-2002 St. Stephen's College, University of Delhi, India B.A.