The Coming of Methodism to Northern Hampshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Martin's Church East Woodhay Index, Catalogue and Condition Of

ST MARTIN’S CHURCH EAST WOODHAY INDEX, CATALOGUE AND CONDITION OF MEMORIAL AND OTHER INSCRIPTIONS 1546-2007 Prepared by Graham Heald East Woodhay Local History Society 2008 Developed from the 1987 Catalogue prepared by A C Colpus, P W Cooper and G G Cooper Hampshire Genealogical Society An electronic copy of this document is available on the Church website www.hantsweb.gov.uk/stmartinschurch First issue: June 2005 Updated and minor corrections: February 2008 St Martin’s Church, East Woodhay Index, Catalogue and Condition of Memorial Inscriptions, 1546 - 2007 CONTENTS Page Abbreviations 1 Plan of Memorial Locations 2 Index 3 Catalogue of Inscriptions and Condition Churchyard, Zone A 11 Churchyard, Zone B 12 Churchyard, Zone C 15 Churchyard, Zone D 28 Churchyard, Zone E 29 Churchyard, Zone F 39 Churchyard, Zone G 43 Church, East Window 45 Church, North Wall (NW) 45 Church, South Wall (SW) 48 Church, West Wall (WW) 50 Church, Central Aisle (CA) 50 Church, South Aisle (SA) 50 Pulpit, Organ and Porch 51 Memorials located out of position (M) 51 Memorials previously recorded but not located (X) 52 The Stained Glass Windows of St Martin’s Church 53 St Martin’s Church, East Woodhay Index, Catalogue and Condition of Memorial Inscriptions, 1546 - 2007 ABBREVIATIONS Form of Memorial CH Cross over Headstone CP Cross over Plinth DFS Double Footstone DHS Double Headstone FS Footstone HS Headstone K Kerb (no inscription) Kerb KR Kerb and Rail (no inscription) PC Prostrate Cross Plinth Slab Slab (typically 2000mm x 1000mm) SS Small Slab (typically 500mm -

The Loddon Valley Link Church and Community Magazine June 2019 Issue 523

The Loddon Valley Link Church and Community Magazine June 2019 Issue 523 Page 1 Minister’s Letter Editorial Dear Friends being true I have to ask myself elcome to the June edition of in. do hope your year is progressing well why I can be patient with others but not so much myself. I the Loddon Valley Link. The The Link will be helping run a stall in and that you are enjoying the summer, year seems to progress with however, at the time of writing I have suspect that I am not the only the ‘Window on Sherfield’ feature at Simon Boase one that reacts in this way. But I relentless abandon. Our the fete so come along, meet the team no idea whether we will be knee deep in swallows are back chasing the mud or not when you receive this. I need to learn to be patient with and tell us what you think of the magazine. Apparently myself and I need to love myself Wcats away from the garage and repairing their nest. there will be competitions and prizes too. Ihave grown lots of plants from seed this year and for Everything has greened up and gardens are blooming more because others do and so does Send your articles, comments and pictures (especially the first time for a number of years I had them all lovely. We had a very interesting village walk last month sown on time. One particular pot of celeriac had me God. God himself knows how many reasons there for the cover) to [email protected] are for him not to be patient with me and yet he is. -

Week Ending 12Th February 2010

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 06 Week Ending: 12th February 2010 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column For the Northern Area to: For the Southern Area to: Head of Planning Head of Planning Beech Hurst Council Offices Weyhill Road Duttons Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ ROMSEY SO51 8XG In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 10/00166/FULLN Erection of two replacement 33 And 34 Andover Road, Red Mr & Mrs S Brown Jnr Mrs Lucy Miranda YES 08.02.2010 dwellings together with Post Bridge, Andover, And Mr R Brown Page ABBOTTS ANN garaging and replacement Hampshire SP11 8BU 12.03.2010 and resiting of entrance gates 10/00248/VARN Variation of condition 21 of 11 Elder Crescent, Andover, Mr David Harman Miss Sarah Barter 10.02.2010 TVN.06928 - To allow garage Hampshire, SP10 3XY 05.03.2010 ABBOTTS ANN to be used for storage room -

ABBOTTS ANN PARISH COUNCIL Newsletter: November 2008

ABBOTTS ANN PARISH COUNCIL Newsletter: November 2008 LEST WE FORGET There is so much to remember in November, but it must be wise for us to have a kind of annual audit of shared and personal memories. Some of us will never forget the tremendous impact in the 1930s of the whole of London stopping dead at 11 o’clock every November 11th with buses at a standstill, shops falling silent, pedestrians standing hatless on the pavements, and even the cycling errand-boys hushing their whistling. There are interesting signs that after the casual attitudes of recent years a more thoughtful approach to remembrance is emerging, even as those with direct experience of war are dwindling in numbers. So, while our heads are whirling with the bewildering complications of the Megashed saga, there is a danger that we will forget that the old airfield, which, after all, is only a few yards from our Parish boundary, is a site of major importance in the history of air warfare. Starting off in 1917 as a base for the Royal Flying Corps, built mainly by German prisoners-of-war, the station was first occupied by the No. 2 School of Navigation and Bomb-dropping. This set the pattern for 60 years of vital work, mainly in the fields of training and research, including the first form of electronic navigation (Radio Direction Finding), which, in principle, is still in use. Between the wars it hosted the RAF Staff College (which did not finally move away until 1970) and numerous experimental and training units. -

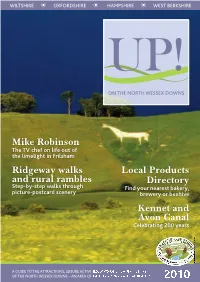

Local Products Directory Kennet and Avon Canal Mike Robinson

WILTSHIRE OXFORDSHIRE HAMPSHIRE WEST BERKSHIRE UP! ON THE NORTH WESSEX DOWNS Mike Robinson The TV chef on life out of the limelight in Frilsham Ridgeway walks Local Products and rural rambles Directory Step-by-step walks through Find your nearest bakery, picture-postcard scenery brewery or beehive Kennet and Avon Canal Celebrating 200 years A GUIDE TO THE ATTRACTIONS, LEISURE ACTIVITIES, WAYS OF LIFE AND HISTORY OF THE NORTH WESSEX DOWNS – AN AREA OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY 2010 For Wining and Dining, indoors or out The Furze Bush Inn provides TheThe FurzeFurze BushBush formal and informal dining come rain or shine. Ball Hill, Near Newbury Welcome Just 2 miles from Wayfarer’s Walk in the elcome to one of the most beautiful, amazing and varied parts of England. The North Wessex village of Ball Hill, The Furze Bush Inn is one Front cover image: Downs was designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in 1972, which means of Newbury’s longest established ‘Food Pubs’ White Horse, Cherhill. Wit deserves the same protection by law as National Parks like the Lake District. It’s the job of serving Traditional English Bar Meals and an my team and our partners to work with everyone we can to defend, protect and enrich its natural beauty. excellent ‘A La Carte’ menu every lunchtime Part of the attraction of this place is the sheer variety – chances are that even if you’re local there are from Noon until 2.30pm, from 6pm until still discoveries to be made. Exhilarating chalk downs, rolling expanses of wheat and barley under huge 9.30pm in the evening and all day at skies, sparkling chalk streams, quiet river valleys, heaths, commons, pretty villages and historic market weekends and bank holidays towns, ancient forest and more.. -

358 940 .Co.Uk

The Villager November 2017 Sherbornes and Pamber 1 04412_Villager_July2012:19191_Villager_Oct07 2/7/12 17:08 Page 40 2 Communications to the Editor: the Villager CONTACTS Distribution of the Villager George Rust and his team do a truly marvellous job of delivering the Villager Editor: magazine to your door. Occasionally, due to a variety of reasons, members of his Julie Crawley team decide to give up this job. Would you be willing to deliver to a few houses 01256 851003 down your road? Maybe while walking your dog, or trying to achieve your 10,000 [email protected] steps each day! George, or I, would love to hear from you. Remember: No distributor = no magazine ! Advertisements: Emma Foreman Welcome to our new local police officer 01256 889215/07747 015494 My name is PCSO Matthew Woods 15973 and I will now be replacing PCSO John [email protected] Dullingham as the local officer for Baughurst, Sherborne St John, Ramsdell, North Tadley, Monk Sherborne, Charter Alley, Wolverton, Inhurst and other local areas. I will be making contact with you to introduce myself properly in the next few weeks Distribution: so I look forward to meeting you all. George Rust If anybody wishes to contact me, my email address is below. 01256 850413 [email protected] Many thanks PCSO 15973 Matthew Woods Work mobile: 07392 314033 [email protected] Message from the Flood and Water Management Team: Future Events: Lindsay Berry Unfortunately it is fast becoming the time of year when we need to think about the state of Hampshire’s land drainage network. -

Towards an Understanding of Lived Methodism

Telling Our Stories: Towards an Understanding of Lived Methodism Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Edwards, Graham M. Citation Edwards, G. M. (2018). Telling Our Stories: Towards an Understanding of Lived Methodism. (Doctoral dissertation). University of Chester, United Kingdom. Publisher University of Chester Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 28/09/2021 05:58:45 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/621795 Telling Our Stories: Towards an Understanding of Lived Methodism Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Chester for the degree of Doctor of Professional Studies in Practical Theology By Graham Michael Edwards May 2018 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The work is my own, but I am indebted to the encouragement, wisdom and support of others, especially: The Methodist Church of Great Britain who contributed funding towards my research. The members of my group interviews for generously giving their time and energy to engage in conversation about the life of their churches. My supervisors, Professor Elaine Graham and Dr Dawn Llewellyn, for their endless patience, advice and support. The community of the Dprof programme, who challenged, critiqued, and questioned me along the way. Most of all, my family and friends, Sue, Helen, Simon, and Richard who listened to me over the years, read my work, and encouraged me to complete it. Thank you. 2 CONTENTS Abstract 5 Summary of Portfolio 6 Chapter One. Introduction: Methodism, a New Narrative? 7 1.1 Experiencing Methodism 7 1.2 Narrative and Identity 10 1.3 A Local Focus 16 1.4 Overview of Thesis 17 Chapter Two. -

East Woodhay

Information on Rights of Way in Hampshire including extracts from “The Hampshire Definitive Statement of Public Rights of Way” Prepared by the County Council under section 33(1) of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949 and section 57(3) of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 The relevant date of this document is 15th December 2007 Published 1st January 2008 Notes: 1. Save as otherwise provided, the prefix SU applies to all grid references 2. The majority of the statements set out in column 5 were prepared between 1950 and 1964 and have not been revised save as provided by column 6 3. Paths numbered with the prefix ‘5’ were added to the definitive map after 1st January 1964 4. Paths numbered with the prefix ‘7’ were originally in an adjoining parish but have been affected by a diversion or parish boundary change since 1st January 1964 5. Paths numbered with the prefix ‘9’ were in an adjoining county on 1st January 1964 6. Columns 3 and 4 do not form part of the Definitive Statement and are included for information only Parish and Path No. Status Start Point (Grid End point (Grid Descriptions, Conditions and Limitations ref and ref and description) description) Footpath 3775 0098 3743 0073 From Road B.3054, southwest of Beaulieu Village, to Parish Boundary The path follows a diverted route between 3810 0150 and East Boldre 703 Beaulieu Footpath Chapel Lane 3829 0170 3 at Parish From B.3054, over stile, southwards along verge of pasture on east side of wire Boundary fence, over stile, south westwards along verge of pasture on southeast side of hedge, over stile, southwards along headland of arable field on east side of hedge, over stile, Beaulieu 3 Footpath 3829 0170 3775 0098 south westwards along verge of pasture on southeast side of hedge, through kissing Hatchet Lane East Boldre gate, over earth culvert, along path through Bulls Wood, through kissing gate, along Footpath 703 at gravel road 9 ft. -

For England Report No. .513

For England Report No. .513 Parish Review BOROUGH OF BASINGSTOKE AND DEANE LOCAL GOVERNlfERT BOUNDARY COMMISSION ••.••" FOH ENGLAND BEPORT NO.SI3 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN Mr G J Ellerton CMG MBE DEPUTY CHAIRMAN Mr J G Powell FRICS FSVA MEMBERS Lady Ackner Mr T Brockbank DL Professor G E Cherry Mr K J L Newell Mr D Scholes OBE THE RIGHT HON. KENNETH BAKER MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT BACKGROUND 1. In a letter dated 20 December 1984 we were informed of your predecessor's decision not to give effect to "our proposals to transfer part of the parish of Monk Sherborne, at Charter Alley, to the parish of Wootton St. Lawrence. He felt that in the light of representations subsequently made to him this element of our proposals warranted further consideration. Accordingly, in exercise of his powers under section 51(3 ) of the Local Government Act 1972 he directed us to undertake a 'further review of the parishes of Monk Sherborne and Wootton St. Lawrence, and to make such revised proposals as we saw fit before 31 December 1985. CONSIDERATION OF DRAFT PROPOSALS 2. In preparing our draft proposals we considered a number of possible alternative approaches to uniting Charter Alley within one parish, bearing in mind the represent- ations made to the Secretary of State. 3. The first was to create a new parish consisting of the northern parts of the existing parishes of Monk Sherborne and Wootton St. Lawrence and bounded in the south by the A339. One difficulty with this approach was that whilst Monk Sherborne Parish Council would have welcomed the idea, Wootton St. -

Church, Place and Organization: the Development of the New

238 CHURCH, PLACE AND ORGANIZATION The Development of the New Connexion General Baptists in Lincolnshire, 1770-18911 The history and developm~nt of the New Connexion of· the General Baptists represented a particular response to the challenges which the Evangelical Revival brought to the old dissenting churches. Any analysis of this response has to be aware of three key elements in the life of the Connexion which were a formative part in the way it evolved: the role of the gathered church, the context of the place within which each church worked and the structures which the organization of the Connexion provided. None of them was unique to it, nor did any of them, either individually, or with another, exercise a predominant influence on it, but together they contributed to the definition of a framework of belief, practice and organization which shaped its distinctive development. As such they provide a means of approaching its history. At the heart of the New Connexion lay the gathered churches. In the words of Adam Taylor, writing in the early part of the nineteenth century, they constituted societies 'of faithful men, voluntarily associated to support the interests of religion and enjoy its privilege, according to their own views of these sacred subjects'. 2 These churches worked within the context of the places where they had been established, and this paper is concerned with the development of the New Connexion among the General Baptist churches of Lincolnshire. Moreover, these Lincolnshire churches played a formative role in the establishment of the New Connexion, so that their history points up the partiCUlar character of the relationship between churches and the concept of a connexion as it evolved within the General Baptist community. -

29.08.2021 Weekly Intercessions

THE PARISH OF THE HOLY TRINITY CHRISTCHURCH WEEKLY INTERCESSIONS Week beginning Sunday 29th August 2021 THE THIRTEENTH SUNDAY AFTER TRINITY PLEASE REMEMBER IN YOUR PRAYERS: PARISH INTERCESSIONS: The sick or those in distress: Phil Aspinall, Brian Barley, Chris Calladine, Isla Drayton, John Franklin, Iain, Marion Keynes, Gill de Maine, Geoffrey Owen, Eileen Parkinson, Richard Passmore, Lynn Pearson, Roméo Ronchesse, Paul Rowsell, Sandra, Sia, Betty Sullivan, The long term sick: Brian Keemer, Denise Wall The housebound and infirm: Those recently departed: Karen Baden, Elizabeth Barr, Brenda Woodward Those whose anniversary of death falls at this time: Christine Sadler (30th), Susan Roberts (1st September), Eileen Wall (1st), Patricia Devall (1st), Joy Saberton (2nd), Daniel Whitcher (4th) ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ANGLICAN COMMUNION & WINCHESTER DIOCESE AND DEANERY INTERCESSIONS: Sunday 29th August The Thirteenth Sunday after Trinity Anglican Cycle: South Sudan: Justin Badi Arama (Archbishop, and Bishop of Juba) Diocesan Life: Chaplaincy: lay and ordained, in prisons, schools, universities, police, hospitals and in our communities; and Anna Chaplains working with older people and chaplains working with those with disability, the deaf & hard of hearing. Deanery: The Area Dean, Canon Gary Philbrick. The Assistant Area Dean , Matthew Trick, The Lay Chair of Synod, Susan Lyonette. Members of the Standing Committee. The Deanery Synod and our representatives on the Diocesan Synod. Kinkiizi Prayers : Kanyantorogo Archdeaconry. Monday 30th August John Bunyan, Spiritual Writer, 1688 Anglican Cycle: Ekiti Kwara (Nigeria): Andrew Ajayi (Bishop) Diocese: Benefice of Burghclere with Newtown and Ecchinswell with Sydmonton: Burghclere: The Ascension; Ecchinswell w Sydmonton: St Lawrence; Newtown: St Mary the Virgin & St John the Baptist. Clergy & LLMs: Priest in Charge: Anthony Smith. -

Proceedings Wesley Historical Society

Proceedings OF THE Wesley Historical Society Editor: REV. JOHN c. BOWMER, M.A., B.O. Volume XXXIV December 1963 CHURCH METHODISTS IN IRELAND R. OLIVER BECKERLEGGE'S interesting contribution on the Church Methodists (Proceedings, xxxiv, p. 63) draws D attention to the fact that the relationship of Methodists with the Established Church followed quite a different pattern in Ireland. Had it not been so, there would have been no Primitive Wesleyan Methodist preacher to bring over to address a meeting in Beverley, as mentioned in that article. Division in Methodism in Ireland away from the parent Wesleyan body was for the purpose of keeping in closer relation with-and not to move further away from-the Established (Anglican) Church of Ireland. Thus, until less than ninety years ago, there was still a Methodist connexion made up of members of the Anglican Church. In Ireland, outside the north-eastern region where Presbyterian ism predominates, tensions between the Roman Catholic and Protestant communities made it seem a grievous wrong to break with the Established Church. In the seventeenth century, the Independent Cromwellian settlers very soon threw in their lot with that Church, which thereby has had a greate~ Protestant Puritan element than other branches of Anglicanism. Even though early Methodism in Ireland showed the same anomalous position regard ing sacraments and Church polity generally, the sort of solution provided in England by the Plan of Pacification was not adopted until 1816, over twenty years later. Those who disagreed were not able to have the decision reversed at the 1817 Irish Conference. Meeting at Clones, they had formed a committee to demand that no Methodist preacher as such should administer the sacraments, and then in 1818, at a conference in Dublin, they established the Primitive Wesleyan Methodist Connexion.