Srynotfunny: Communicative Functions of Hashtags on Twitter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GALAXIES PART 1 (These Are the Video Notes from the Crash Course Video)

CRASH COURSE ASTRONOMY: GALAXIES PART 1 (these are the video notes from the crash course video) We live in a pretty cool neighborhood: the Milky Way Galaxy. We're out in the suburbs, sure, but it's still an interesting place, buzzing with activity: stars, nebulae, stellar clusters of various sorts, the occasional supernova. It's a happening place. In the earliest part of the 20th Century, astronomers were just starting to figure this all out. But there were a handful of objects that were puzzling. Dotting the sky here and there were faint fuzzies displaying a variety of shapes. Some were round, some elongated, and some even seemed to have spiral arms. Even with big telescopes, they looked smoky, so they were simply called nebulae. Their existence was puzzling though. What were they? How did they form? Were they big? Small? Near? Far? Eventually, astronomers had uncovered the key to these objects, and in one fell swoop, our universe got a lot bigger. A lot. (Intro) In 1920, there were two competing ideas about the universe. One was that our Milky Way was it, and that everything we saw was in it. The other was that these spiral nebulae seen in the sky were also like our Milky Way, island universes in their own right. Two astronomers debated this controversy in that year. Harlow Shapley argued that the Milky Way was all there is, while Heber Curtis was of the opinion that we were one of many galaxies. It wasn't a debate as such, more of a presentation of ideas, and there was no clear winner. -

Mil Veces Hasta Siempre Para Henry Y Alice El Hombre Puede Hacer Lo Que Quiera, Pero No Puede Querer Lo Que Quiera

Cortesía de LibreríaPDF Encontrá muchos más libros en: www.libreriapdf.com JOHN GREEN Mil veces hasta siempre Para Henry y Alice El hombre puede hacer lo que quiera, pero no puede querer lo que quiera. ARTHUR SCHOPENHAUER 1 La primera vez que caí en la cuenta de que yo podría ser un personaje de ficción, asistía de lunes a viernes a un centro público del norte de Indianápolis llamado White River High School, en el que fuerzas muy superiores a mí que no podía siquiera empezar a identificar me exigían comer a una hora concreta: entre las 12:37 y las 13:14. Si esas fuerzas me hubieran asignado un horario de comida diferente, o si los compañeros de mesa que ayudaban a escribir mi destino hubieran elegido otro tema de conversación aquel día de septiembre, yo habría tenido un final diferente, o al menos un nudo narrativo diferente. Pero empezaba a descubrir que tu vida es una historia que cuentan sobre ti, no una historia que cuentas tú. Crees que eres el autor, por supuesto. Tienes que serlo. Cuando el monótono timbre suena a las 12:37, piensas: «Ahora decido ir a comer». Pero en realidad el que decide es el timbre. Crees que eres el pintor, pero eres el cuadro. En la cafetería, cientos de gritos se superponían, de modo que la conversación se convirtió en un mero sonido, en el rumor de un río avanzando sobre las piedras. Y mientras me sentaba debajo de fluorescentes cilíndricos que escupían una agresiva luz artificial, pensaba que todos nos creíamos protagonistas de alguna epopeya personal, cuando en realidad éramos básicamente organismos idénticos colonizando una sala enorme sin ventanas que olía a desinfectante y a grasa. -

Phil Plait's Bad Astronomy Misconceptions

Phil Plait's Bad Astronomy: Misconceptions 10/13/08 11:07 AM Blog Intro What's New? Bad Astronomy Misconceptions Movies News TV Free Planets Screensavers BA Blog Bring the Universe Alive on Your PC 100% Free Screensaver. Screensaver.com/Planets Q & BA Full-Svc Proposal Support Bulletin Board 83% Win Rate; 97% Return Clients Consultants in every labor category www.OCIwins.com Media My PR Kit Burr Pilger Mayer Radio One of the Bay Areas Top Accounting /Tax In Print Management Firms. Learn more.. www.bpmllp.com Bitesize Astronomy Withholding Hubble Space Telescope Data Book Store Bad: Bad Astro In general, withholding Hubble Space Telescope data is a bad thing. Store Good: Mad Science Actually, it is a very good thing; it improves the quality of the knowledge received from the data. Note: This is a long article; the longest Bad Astronomy to date. This particular issue is one near and dear to me, so please bear with me! Fun Stuff How it works: Site Info The idea that withholding Hubble Space Telescope (HST) data is bad is not Search the site something I have heard about in the media, but does seem to have some internet staying power. I have seen three general attitudes about it: Who am I? Contact me 1. People simply being curious as to why HST data are withheld from public view Public Talks for a year, Calendar/Events Check out my 2. People that think a NASA conspiracy is doing this, and book "Bad Links Astronomy" 3. People that feel that as taxpayers they have a right to immediate access to the data. -

Astronomy 152 Fall 2021 Syllabus

Astronomy 152 - Fall 2021 Syllabus Stars, Galaxies, and Cosmology Fall 2021 Semester University of Tennessee, Knoxville Course Details Instructor: Dr. Sean Lindsay E-mail: [email protected] (he/him/his) Class Times: 9:15 - 10:05 AM Monday, Wednesday, and Friday (MWF) Class Location: PHYS 415 in Nielsen Physics and Astronomy Building Course Number: ASTR 152-001 Dr. Lindsay’s Office: PHYS 215 in Nielsen Physics & Astronomy Building Phone: 865-974-2362 (leave voicemail) Zoom Office Hours: In-Office: Mondays: 11 am - 12 pm or by Appointment Tuesdays: 3 pm – 4 pm or by Appointment Virtual: Available by appointment. Zoom Link: https://tennessee.zoom.us/j/96905649825 Passcode: HA6563 Course TAs: Jesse Farr Hannah Garrett [email protected] [email protected] Michelle Simpson [email protected] Course Resources: Fall 2021 Semester Schedule: Link to Schedule Textbook: No Official Course Textbook. No purchase necessary I rely on my extensive course notes provided to you for free. Going through the PowerPoint version in presenter mode is recommended to see all of the animations. Additional Text Resource: Openstax’s Astronomy Link: https://openstax.org/details/books/astronomy?Book%20details (Not required in any way for this course) Crash Course Astronomy with Dr. Phil Plait (Great for review & reinforcement) Hyperlink to Youtube Channel: Link Course Website: Canvas Required Course Materials: Calculator GroupMe: Invite Link Discord Server: Invite Link Course Policies in Brief ● Attendance is not mandatory ● There is no required textbook or homework platform purchase. ● Must complete weekly exercises called Engagement Exercises (15% of grade) ● Must complete all homework assignments - No homework will be dropped (35% of grade) ● Must complete all 6 quizzes - No quizzes will be dropped, but final quiz grade will be calculated out of 66 instead of the available 72 quiz points. -

SKY Journal of Linguistics

Volume 27:2014 sky SKY Journal of Linguistics Editors: Markus Hamunen, Tiina Keisanen, Hanna Lantto, Lotta Lehti, Saija Merke SKY Journal of Linguistics is published by the Linguistic Association of Finland (one issue per year). Notes for Contributors Policy: SKY Journal of Linguistics welcomes unpublished original works from authors of all nationalities and theoretical persuasions. Every manuscript is reviewed by at least two anonymous referees. In addition to full-length articles, the journal also accepts short (3–9 pages) ‘squibs’ as well as book reviews. Language of Publication: Contributions should be written in English, French, or German. If the article is not written in the native language of the author, the language should be checked by a qualified native speaker. Style Sheet: A detailed style sheet is available from the editors, as well as via WWW at http://www.linguistics.fi/skystyle.shtml. Abstracts: Abstracts of the published papers are included in Linguistics Abstracts and Cambridge Scientific Abstracts. The published papers are included in EBSCO Communication & Mass Media Complete. SKY JoL is also indexed in the MLA Bibliography. Editors’ Addresses (2014): Markus Hamunen, School of Language, Translation and Literary Studies, Kalevantie 4, FI- 33014, University of Tampere, Finland Tiina Keisanen, Faculty of Humanities, P.O. Box 1000, FI-90014 University of Oulu, Finland Hanna Lantto, Department of Modern Languages, P.O. Box 24, Unioninkatu, FI-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland Lotta Lehti, French Department, Koskenniemenkatu 4, FI-20014 University of Turku, Finland Saija Merke, Department of Finnish, Finno-Ugrian and Scandinavian Studies, P.O. Box 3, Fabianinkatu 33, FI-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland Editors’ E-mail: sky-journal(at)helsinki(dot)fi Publisher: The Linguistic Association of Finland c/o General Linguistics P.O. -

Doctora Honoris Causa Lisa Randall

Doctora honoris causa Lisa Randall Doctora honoris causa LISA RANDALL Discurs llegit a la cerimònia d’investidura celebrada a la sala d’actes de l’edifici Rectorat el dia 25 de març de l’any 2019 Índex Presentació de Lisa Randall per Àlex Pomarol Clotet 5 Discurs de Lisa Randall 13 Discurs de Margarita Arboix, rectora de la UAB 21 Curriculum vitae de Lisa Randall 27 Acord de Consell de Govern 131 PRESENTACIÓ DE LISA RANDALL PER ÀLEX POMAROL CLOTET És un plaer ser el padrí de la professora Lisa Randall, una persona que ha destacat per les seves contribucions en el camp de la física de partícules Les teories proposades per la professora Lisa Randall han mirat de resoldre alguns dels problemes més importants dins de la física de partícules i han inspirat una àmplia gamma de cerques ex- perimentals, especialment en el gran col·lisionador de partícules LHC del CERN a Ginebra, però també dins de l’àmbit astrofísic, motivades per les seves propostes per l’origen de la matèria fosca de l’univers Tot i això, l’interès de la professora Lisa Randall s’ha estès més enllà de la recerca d’avantguarda i també s’ha centrat a transmetre aquests coneixements al públic general Això ho ha fet possible no sols grà- cies als seus llibres de divulgació sinó també mantenint una estreta col·laboració amb artistes per obrir nous camins per portar al públic les idees científiques. En aquest aspecte, la professora Lisa Randall ha sabut relacionar els coneixements del seu camp amb els de la filosofia, les humanitats i la música, com veurem a continuació Professor -

Dr. Phil Plait Speaker, Author, Astronomer

Dr. Phil Plait Speaker, Author, Astronomer For as long as he can remember, Phil Plait has been in love with science: "When I was maybe four or five years old, my dad brought home a cheapo department store telescope. He aimed it at Saturn that night. One look, and that was it. I was hooked," he says. After earning his doctorate in astronomy at the University of Virginia, he worked as a NASA contractor at the Goddard Space Flight Center, working with the Hubble Space Telescope. Dr. Plait began a career in public outreach and education with the 'Bad Astronomy' website and blog, debunking bad science and popular misconceptions. In 2008 he became the President of the James Randi Educational Foundation, a non-profit educational foundation dedicated to promoting critical thinking. Dr. Plait has given dozens of talks about science and pseudo-science across the US and internationally. He uses images, audio, and video clips in an entertaining and informative multimedia presentation packed with humor and backed by solid science. He has spoken at NASA's Kennedy Space Center, NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center, the Space Telescope Science Institute (home of Hubble), the Hayden Planetarium in NYC and many other world-class museums and planetaria, conferences, astronomy clubs, colleges & universities, and community groups. He has appeared on CNN, Fox News, MSNBC, Pax TV, Tech TV, the SciFi Channel, Radio BBC, Air America, NPR, and many other television and internet venues. The Bad Astronomy website receives more than 6 million hits per year and received the 'Best Science Blog' Weblog award in 2007. -

KPCC-KPCV-KUOR Quarterly Report JAN-MAR 2012

Quarterly Programming Report Jan- Mar 2012 KPCC / KPCV / KUOR Date Key Synopsis Guest/Reporter Duration Pasadena Police Department will deploy more officers as Occupy activists plan to demonstrate at the 1/1/2012 POLI Rose Parade. CC :19 Skiers and snowboarders across the western United States face a "snow drought" this winter on some 1/1/2012 SPOR of their favorite slopes. Unknown :16 The three-year old Clean Trucks Program at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach moves into its 1/1/2012 TRAN final phase as the year begins. Peterson :58 1/1/2012 LAW Another dozen arson fires broke out overnight in Los Angeles and West Hollywood. CC :17 1/1/2012 ART Native American creation story and bird songs come alive in new Riverside art exhibition. Cuevas 1:33 1/1/2012 MEDI We asked KPCC listeners to look back on 2011 and ahead to 2012. CC :13 1/1/2012 DC Congressmangpyy shares a New Year's Day breakfast recipe. Felde 1:33 contract with United Teachers Los Angeles – an unprecedented agreement that Deasy called “groundbreaking work,” aimed at providing more freedom for teachers, school administrators and 1/2/12 YOUT parents top,gpggpp, manage their respective schools. John Deasy 00:31 of course. Comedy Congress has hung up its Christmas stocking and finds it full of Mitt and Newt and Barack – and it’s our holiday gift to you. Perry ups the voting age; Obama very politely asks Iran for his Alonzo Bodden, Greg 1/2/12 POLI drone back and we play the highlight reel of Cain’s self-described brain twirlings! And just as we thoughtProops, Ben Gleib 00:65 Dr. -

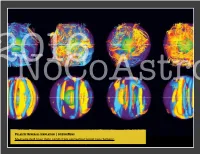

Magnetic Field Lines (Top) Result from Convecting Liquid Iron (Bottom)

2016NoCoAstro POLARITY REVERSAL SIMULATION | SCIENCENEWS Magnetic field lines (top) result from convecting liquid iron (bottom) OUR JOURNEY How much do you really know about the pale blue dot? EDITOR Amanda Bell CONTACT Questions, comments, submissions, photos or just to say ‘hello’: ObjView at NoCoAstro dot org April NoCoAstro NOCOASTRO MEETING Join us for our monthly awesomely-nerdy astro talk: Date: Thursday, May 5th, 6:15-7:45pm Speaker: TBD If you know someone who would like to dazzle the club with their astronomical knowledge, please contact Bob: VP at NoCoAstro dot org. DID YOU KNOW…? All meetings are FREE & open to the public! Just stop by the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery. NOCOASTRO OUTREACH MAY MAY 11th, Wednesday Poudre Learning Center, 8:30pm 13th, Friday Fossil Creek Reservoir, 8:30pm 27th, Friday Bobcat Ridge (pre-register), 8:45pm April 28th, Saturday Carter Lake (park fee req’d), 9pm H OME, SWEET EARTH ORIGIN OF NAME: Our planetary home has been called Earth for at least 1000 years. Did you know that Earth is the only planet that wasn't named after a Greek or Roman god or goddess? ATMOSPHERE TYPE: As you probably remember from elementary school, our atmosphere is primarily oxygen (~20%) and nitrogen (~78%) by volume. Our atmosphere thins with increasing altitude and 3/4 of it is within 6.8 miles (11km) of the surface. You may be saying to yourself, ‘That’s great but where does Earth end & space begin?’ Good question. MOONS: Surely we have one moon, right? Simply put, moons are just natural satellites. -

“Bad Astronomer,” Dr. Phil Plait

NASA Blueshift - 2012 http://universe.nasa.gov/blueshift Keeping Skepticism Alive, Part 1 of our Interview with “Bad Astronomer,” Dr. Phil Plait [music] Maggie Masetti: Welcome to Blueshift, brought to you from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. I'm Maggie Masetti. Both Sara and I been involved with science education and public outreach, and not only with NASA Blueshift. The job of taking science and trying to explain it to the public so that it’s not only understandable but correct is often a challenge. But we both feel it’s so important that the public (as well as the next generation of kids) care about what NASA is doing, and more than that, we want people to have an interest or a curiosity in how the world (and the universe) work. The questions are, how DO you make people care? What’s the best way to convey how awesome science can be? And how do you combat the misinformation and superstition that are already out there? Since this is a subject we’ve spent a lot of time discussing amongst ourselves, we thought we’d consult some other well-known names in the field of mythbusting. The first of these is the so-called “Bad Astronomer”, Dr. Phil Plait. Phil used to work here at NASA Goddard, but is now a full-time writer and advocate for both good science and the busting of misconceptions. This podcast is the first part of our interview with him, in which we learn what makes him the “Bad Astronomer”, why he blogs about misconceptions, and how to help keep skepticism alive. -

Denying the Apollo Moon Landings: Conspiracy and Questioning in Modern American History

Denying the Apollo Moon Landings: Conspiracy and Questioning in Modern American History Roger D. Launius* Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20650 I. Abstract Almost from the point of the first Apollo missions, a small group of Americans denied that it had taken place at all. It had, they argued, been faked in Hollywood by the federal government for purposes ranging—depending on the particular Apollo landing denier—from embezzlement of the public treasury to complex conspiracy theories involving international intrigue and murderous criminality. They tapped into a rich vein of distrust of government, populist critiques of society, and questions about the fundamentals of epistemology and knowledge creation. At the time of the first landings, opinion polls showed that overall less than five percent, among some communities larger percentages, ―doubted the moon voyage had taken place.‖1 For example, Andrew Chaikin commented in his massive history of the Apollo Moon expeditions that at the time of the Apollo 8 circumlunar flight in December 1968 some people thought it was not real; instead it was ―all a hoax perpetrated by the government.‖ Bill Anders, an astronaut on the mission, thought live television would help convince skeptics since watching ―three men floating inside a spaceship was as close to proof as they might get.‖2 He could not have been more wrong. Fueled by conspiracy theorists of all stripes, this number has grown over time. In a 2004 poll, while overall numbers remained about the same, among Americans between 18 and 24 years old ―27% expressed doubts that NASA went to the Moon,‖ according to pollster Mary Lynne Dittmar. -

ASD Annual Report 2012

The Astrophysics Science Division Annual Report 2012 Astrophysics Science Division The NASA/TM-2013-217509 Goddard’s Astrophysics Science Division Annual Report 2012 Padi Boyd and Francis Reddy, Editors Pat Tyler, Graphical Editor NASA/TM-2013-217509 NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland 20771 May 2013 The NASA STI Program Offi ce … in Profi le Since its founding, NASA has been ded i cated to the • CONFERENCE PUBLICATION. Collected ad vancement of aeronautics and space science. The pa pers from scientifi c and technical conferences, NASA Sci en tifi c and Technical Information (STI) symposia, sem i nars, or other meetings spon sored Pro gram Offi ce plays a key part in helping NASA or co spon sored by NASA. maintain this impor tant role. • SPECIAL PUBLICATION. Scientifi c, tech ni cal, The NASA STI Program Offi ce is operated by or historical information from NASA pro grams, Langley Research Center, the lead center for projects, and mission, often concerned with sub- NASAʼs scientifi c and technical in for ma tion. The jects having substan tial public interest. NASA STI Program Offi ce pro vides ac cess to the NASA STI Database, the largest collec tion of • TECHNICAL TRANSLATION. En glish-language aero nau ti cal and space science STI in the world. trans la tions of foreign scien tifi c and tech ni cal ma- The Pro gram Offi ce is also NASAʼs in sti tu tion al terial pertinent to NASAʼs mis sion. mecha nism for dis sem i nat ing the results of its research and devel op ment activ i ties.