Click Here to Read the Court Filing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HBO S I LL BE GONE in the DARK Returns with a Special Episode June 22

HBO’s I’LL BE GONE IN THE DARK Returns With A Special Episode June 22 The Story Syndicate Production Marks One Year Since The Guilty Plea Of Joseph James DeAngelo, The Golden State Killer I’LL BE GONE IN THE DARK returns with a special episode directed by Elizabeth Wolff (HBO’s “I’ll Be Gone in the Dark”) and executive produced by Liz Garbus (HBO’s “I’ll Be Gone in the Dark,” “Who Killed Garrett Phillips?” and “Nothing Left Unsaid: Gloria Vanderbilt & Anderson Cooper). The critically acclaimed six-part documentary series based on the best-selling book of the same name debuted in June 2020 and explores writer Michelle McNamara’s investigation into the dark world of the violent predator she dubbed "The Golden State Killer.” This special episode debuts TUESDAY, JUNE 22 on HBO. Times per country visit Hbocaribbean.com Synopsis: In the summer of 2020, former police officer Joseph James DeAngelo, also known as the Golden State Killer, was sentenced to life in prison for the 50 home-invasion rapes and 13 murders he committed during his reign of terror in the 1970s and ‘80s in California. Many of the survivors and victim’s family members featured in the series reconvened for an emotional public sentencing hearing in August 2020, where they were given the opportunity to speak about their long-held pain and anger through victim impact statements, facing their attacker directly for the first time and bringing a sense of justice and resolution to the case. Writer Michelle McNamara was key to keeping the Golden State Killer case alive and in the public eye for so many years, but passed away in 2016, before she could witness the impact of her relentless determination in seeking justice for the victims. -

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

Ethics and True Crime: Setting a Standard for the Genre

Portland State University PDXScholar Book Publishing Final Research Paper English 5-12-2020 Ethics and True Crime: Setting a Standard for the Genre Hazel Wright Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/eng_bookpubpaper Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Publishing Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Wright, Hazel, "Ethics and True Crime: Setting a Standard for the Genre" (2020). Book Publishing Final Research Paper. 51. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/eng_bookpubpaper/51 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Book Publishing Final Research Paper by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Ethics and True Crime: Setting a Standard for the Genre by Hazel Wright May 12, 2020 RESEARCH QUESTION What are the perceived ethical problems with true crime as a genre? What considerations should be included in a preliminary ethical standard for true-crime literature? ABSTRACT True crime is a genre that has existed for centuries, adapting to social and literary trends as they come and go. The 21st century, particularly in the last five years, has seen true crime explode in popularity across different forms of media. As the omnipresence of true crime grows, so to do the ethical dilemmas presented by this often controversial genre. This paper examines what readers perceive to be the common ethical problems with true crime and uses this information to create a preliminary ethical standard for true-crime literature. -

April New Books

BROWNELL LIBRARY NEW TITLES, APRIL 2018 FICTION F ALBERT Albert, Susan Wittig. Queen Anne's lace / Berkley Prime Crime, 2018 While helping Ruby Wilcox clean up the loft above their shops, China comes upon a box of antique handcrafted lace and old photographs. Following the discovery, she hears a woman humming an old Scottish ballad and smells the delicate scent of lavender. Soon strange things start occurring. Could the building be haunted? F ARDEN Arden, Katherine. The bear and the nightingale: a novel / Del Rey, 2017 A novel inspired by Russian fairy tales follows the experiences of a wild young girl who taps the mysterious powers of a precious necklace given to her father years earlier to save her village from dark and dangerous forces. F BALDACCI Baldacci, David. The fallen / Grand Central Publishing, 2018 Amos Decker and his journalist friend Alex Jamison are visiting the home of Alex's sister in Barronville, a small town in western Pennsylvania that has been hit hard economically. When Decker is out on the rear deck of the house talking with Alex's niece, a precocious eight-year- old, he notices flickering lights and then a spark of flame in the window of the house across the way. When he goes to investigate he finds two dead bodies inside and it's not clear how either man died. But this is only the tip of the iceberg. There's something going on in Barronville that might be the canary in the coal mine for the rest of the country. Faced with a stonewalling local police force, and roadblocks put up by unseen forces, Decker and Jamison must pull out all the stops to solve the case. -

Frequencies Between Serial Killer Typology And

FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS A dissertation presented to the faculty of ANTIOCH UNIVERSITY SANTA BARBARA in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY in CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY By Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori March 2016 FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS This dissertation, by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, has been approved by the committee members signed below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of Antioch University Santa Barbara in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Committee: _______________________________ Ron Pilato, Psy.D. Chairperson _______________________________ Brett Kia-Keating, Ed.D. Second Faculty _______________________________ Maxann Shwartz, Ph.D. External Expert ii © Copyright by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, 2016 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS LERYN ROSE-DOGGETT MESSORI Antioch University Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA This study examined the association between serial killer typologies and previously proposed etiological factors within serial killer case histories. Stratified sampling based on race and gender was used to identify thirty-six serial killers for this study. The percentage of serial killers within each race and gender category included in the study was taken from current serial killer demographic statistics between 1950 and 2010. Detailed data -

Medical Management of Biologic Casualties Handbook

USAMRIID’s MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF BIOLOGICAL CASUALTIES HANDBOOK Fourth Edition February 2001 U.S. ARMY MEDICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES ¨ FORT DETRICK FREDERICK, MARYLAND 1 Sources of information: National Response Center 1-800-424-8802 or (for chem/bio hazards & terrorist events) 1-202-267-2675 National Domestic Preparedness Office: 1-202-324-9025 (for civilian use) Domestic Preparedness Chem/Bio Help line: 1-410-436-4484 or (Edgewood Ops Center - for military use) DSN 584-4484 USAMRIID Emergency Response Line: 1-888-872-7443 CDC'S Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Center: 1-770-488-7100 John's Hopkins Center for Civilian Biodefense: 1-410-223-1667 (Civilian Biodefense Studies) An Adobe Acrobat Reader (pdf file) version and a Palm OS Electronic version of this Handbook can both be downloaded from the Internet at: http://www.usamriid.army.mil/education/bluebook.html 2 USAMRIID’s MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF BIOLOGICAL CASUALTIES HANDBOOK Fourth Edition February 2001 Editors: LTC Mark Kortepeter LTC George Christopher COL Ted Cieslak CDR Randall Culpepper CDR Robert Darling MAJ Julie Pavlin LTC John Rowe COL Kelly McKee, Jr. COL Edward Eitzen, Jr. Comments and suggestions are appreciated and should be addressed to: Operational Medicine Department Attn: MCMR-UIM-O U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) Fort Detrick, Maryland 21702-5011 3 PREFACE TO THE FOURTH EDITION The Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook, which has become affectionately known as the "Blue Book," has been enormously successful - far beyond our expectations. Since the first edition in 1993, the awareness of biological weapons in the United States has increased dramatically. -

Hattori Hachi.’ My Favourite Books

Praise for ‘A great debut novel.’ The Sun ‘Hattie is joined on her terrifying adventures by some fantastic characters, you can’t help but want to be one of them by the end – or maybe you’re brave enough to want to be Hattie herself . .’ Chicklish ‘Hachi is strong, independent, clever and remarkable in every way . I can’t shout loud enough about Hattori Hachi.’ My Favourite Books ‘Jane Prowse has completely nailed this novel. I loved the descriptions, the action, the heart-stopping moments where deceit lurks just around the corner. The story is fabulous, while almost hidden profoundness is scattered in every chapter.’ Flamingnet reviewer, age 12 ‘Hattori Hachi is like the female Jackie Chan, she has all the ninjutsu skills and all the moves! The Revenge of Praying Mantis is one of my all time favourite books! I love the fact that both boys and girls can enjoy it.’ Jessica, age 12 ‘I couldn’t put this book down – it was absolutely brilliant!’ Hugo, age 9 ‘This delightful book is full of ninja action and packed with clever surprises that will hook anyone who reads it!’ Hollymay, age 15 ‘This was the best book I’ve ever read. It was exciting and thrilling and when I started reading it, I could not put it back down.’ Roshane, age 18 ‘Amazing! Couldn’t put it down. Bought from my school after the author’s talk and finished it on the very next day! Jack, age 12 This edition published by Silver Fox Productions Ltd, 2012 www.silverfoxproductions.co.uk First published in Great Britain in 2009 by Piccadilly Press Ltd. -

June 25, 2020 Telephone: 805-654-5082 Release No.: 20-054 E-Mail: [email protected]

GREGORY D. TOTTEN District Attorney NEWS RELEASE www.vcdistrictattorney.com Twitter: @VenturaDAOffice Contact: Cheryl M. Temple Approved: CMT Title: Chief Assistant Date: Thursday, June 25, 2020 Telephone: 805-654-5082 Release No.: 20-054 E-mail: [email protected] Announcement Regarding People v. DeAngelo VENTURA, California – District Attorney Gregory D. Totten alerts the public to the following announcement regarding People v. Joseph James DeAngelo. PRESS CONFERENCE: A joint press conference will be held immediately after the court hearing for People vs. Joseph James DeAngelo. WHEN: Monday, June 29, 2020 ~ to start at approximately 3:00 p.m. WHERE: Sacramento State University Union Ballroom 600 J Street, Sacramento 95819 (directions) SPEAKERS: - Sacramento County District Attorney Anne Marie Schubert - Contra Costa County District Attorney Diana Becton - Orange County District Attorney Todd Spitzer - Santa Barbara County District Attorney Joyce Dudley - Tulare County District Attorney Tim Ward - Ventura County District Attorney Gregory D. Totten • Limited Q&A and interview opportunities with speakers and victims to follow • Open to credentialed media only ~ space is limited and on a first-come, first-served basis • Media must RSVP in-person attendance to [email protected] by Saturday, June 27 at 5 p.m. • A media call-in line is available for credentialed media and information will be provided upon request by emailing [email protected] by Saturday, June 27 at 5 p.m. • To schedule one-on-one interviews with DA Totten after the press conference, please email [email protected] by Saturday, June 27 at 5:00 p.m. • Court hearing will be livestreamed on Sacramento Superior Court’s YouTube for Department 24 linked here • Press conference will be livestreamed on the Sacramento County District Attorney’s YouTube channel linked here and website linked here Press conference attendees will be subject to a temperature check and required to wear a face covering. -

Architecture Program Report for 2012 NAAB Visit for Continuing Accreditation

Harvard Graduate School of Design Department of Architecture Architecture Program Report for 2012 NAAB Visit for Continuing Accreditation Master of Architecture Undergraduate degree outside of Architecture + 105 graduate credit hours Related pre-professional degree + 75 graduate credit hours Year of the Previous Visit: 2006 Current Term of Accreditation: At the July 2006 meeting of the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB), the board reviewed the Visiting Team Report for the Harvard University Department of Architecture. As a result, the professional architecture program: Master of Architecture was formally granted a six-year term of accreditation. The accreditation term is effective January 1, 2006. The program is scheduled for its next accreditation visit in 2012. Submitted to: The National Architectural Accrediting Board Date: 14 September 2011 Harvard Graduate School of Design Architecture Program Report September 2011 Program Administrator: Jen Swartout Phone: 617.496.1234 Email: [email protected] Chief administrator for the academic unit in which the program is located (e.g., dean or department chair): Preston Scott Cohen, Chair, Department of Architecture Phone: 617.496.5826 Email: [email protected] Chief Academic Officer of the Institution: Mohsen Mostafavi, Dean Phone: 617.495.4364 Email: [email protected] President of the Institution: Drew Faust Phone: 617.495.1502 Email: [email protected] Individual submitting the Architecture Program Report: Mark Mulligan, Director, Master in Architecture Degree Program Adjunct Associate Professor of Architecture Phone: 617.496.4412 Email: [email protected] Name of individual to whom questions should be directed: Jen Swartout, Program Coordinator Phone: 617.496.1234 Email: [email protected] 2 Harvard Graduate School of Design Architecture Program Report September 2011 Table of Contents Section Page Part One. -

The Sabre's Edge June 2021

SA BRE' S ED GE THE VOI CE OF SCHALM ONT June 2021 INSIDE THIS ISSUE Class of 2021 ...................... 1-2 CLASS OF Senior Formal ......................... 3 2021 "Unmasked" # 1 .................... 4 "Unmasked" # 2 ..................... 5 Book Review .......................... 5 "Unmasked" # 3 .................... 6 Drama Club ........................... 7 Podcast Review ..................... 8 This year, the Senior class has had to overcome many challenges Your Voice ............................. 9 that the COVID pandemic brought. In the Fall, they faced new school The Marathon ....................... 9 policies that included mask wearing, sitting 6 feet apart, hybrid learning, and only seeing half of their class; that is, when they "Unmasked" # 4 ................... 10 weren?t quarantined. Because of this, they also didn?t get to have Bookface ................................ 10 many of their traditional fall activities such as a Spirit Week, Ronald McDonald House ..... 11 Homecoming games and dances, pep rallies, or the beloved Powder Puff football game. This could have ruined their Senior experience. From Our Editors .................. 12 But our Seniors persevered. They made their Spring activities as fun and memorable as possible. They designed and made their Senior IMPORTANT DATES T-Shirts, took a field trip to Rollarama, had a beautiful Senior Formal at River Stone Manor, planned and took part in a Senior Spirit Week, and in the last few days of school will do a graduation walk-through June 16: Last Day of Classes at Jefferson Elementary and have their Senior Send-Off event. June 25: Last Day of School These Seniors have proven their resilience and dedication to their June 25: Graduat ion! academics and school community by taking everything in stride and trying to make the best of a very difficult year. -

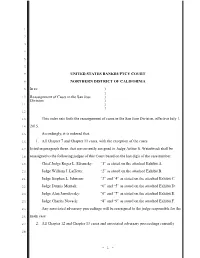

1 - 1 Assigned to Judge Arthur S

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT 8 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA In re: 9 ) ) 10 Reassignment of Cases in the San Jose ) Division ) 11 ) ) 12 13 This order sets forth the reassignment of cases in the San Jose Division, effective July 1, 14 2015. 15 Accordingly, it is ordered that: 16 1. All Chapter 7 and Chapter 11 cases, with the exception of the cases 17 listed in paragraph three, that are currently assigned to Judge Arthur S. Weissbrodt shall be 18 reassigned to the following judges of this Court based on the last digit of the case number: 19 Chief Judge Roger L. Efremsky: “1” as stated on the attached Exhibit A. 20 Judge William J. Lafferty: “2” as stated on the attached Exhibit B. 21 Judge Stephen L. Johnson: “3” and “4” as stated on the attached Exhibit C. 22 Judge Dennis Montali: “0” and “5” as stated on the attached Exhibit D. 23 Judge Alan Jaroslovsky: “6” and “7” as stated on the attached Exhibit E. 24 Judge Charles Novack: “8” and “9” as stated on the attached Exhibit F. 25 Any associated adversary proceedings will be reassigned to the judge responsible for the 26 main case. 27 2. All Chapter 12 and Chapter 13 cases and associated adversary proceedings currently 28 - 1 - 1 assigned to Judge Arthur S. Weissbrodt shall be reassigned to Judge M. Elaine Hammond. In 2 addition, all Salinas Chapter 12 and Chapter 13 cases and associated adversary proceedings shall 3 be reassigned from Judge M. Elaine Hammond to Judge Hannah L. -

Ethical Implications of Forensic Genealogy in Criminal Cases

The Journal of Business, Entrepreneurship & the Law Volume 13 Issue 2 Article 6 5-15-2020 Ethical Implications of Forensic Genealogy in Criminal Cases Solana Lund Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/jbel Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, Privacy Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Solana Lund, Ethical Implications of Forensic Genealogy in Criminal Cases, 13 J. Bus. Entrepreneurship & L. 185 (2020) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/jbel/vol13/iss2/6 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of Business, Entrepreneurship & the Law by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. ETHICAL IMPLICATIONS OF FORENSIC GENEALOGY IN CRIMINAL CASES Solana Lund* I. FORENSIC GENEALOGY .................................................186 II. DIRECT TO CONSUMER DATABASES ..........................189 A. Terms and Conditions ......................................... 189 B. Regulations ......................................................... 192 C. GEDmatch........................................................... 193 III. A SUMMARY OF CRIMINAL CASES THAT HAVE USED DTC AND FORENSIC GENEALOGY ...............................195 IV. ETHICAL IMPLICATIONS