Agreed Report on the Local/Universal Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mary's Notebook

Mary’s Notebook October – November 2009 www.legionofmarytidewater. com Issue 35 Section Page Front Page 1 USCCB Healthcare Letter News & Events 2 Handbook Study 3-4 As our special extra this month, we are attaching a copy of Divine Mysteries 5-12 the bulletin insert being printed nation-wide by the United Legion Spirit 12-14 States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Special/Extra 15 Prayer Requests Order of Praesidium Meeting Please continue to pray for the This is our fifth in a series of articles describing the Praesidium people and intentions that are meeting. In this issue, we discuss section six of the order of the praesidium meeting, which addresses the reading of the listed in Mary’s Notebook, and submit prayer requests to us at: praesidium minutes. It is the duty of every member to listen to webmaster@legionofmarytidewa the minutes without interrupting them, and then – after the ter.com . (Continued on page 2) reading of the minutes is concluded—to discuss any corrections needed in the minutes, before approving them. (Continued on page 3) Divine Mysteries: The Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redintegratio -- Decree on Ecumenism INTRODUCTION 1. The restoration of unity among all Christians is one of the principal concerns of the Second Vatican Council. Christ the Lord founded one Church and one Church only. However, many Christian communions present themselves to men as the true inheritors of Jesus Christ; all indeed profess to be followers of the Lord but differ in mind and go their different ways, as if Christ Himself were divided.(1) Such division openly contradicts the will of Christ, scandalizes the world, and damages the holy cause of preaching the Gospel to every creature. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

WELCOME to the CATHEDRAL of ALL

BETHESDA EPISCOPAL CHURCH Washington Street near Broadway Saratoga Springs, New York 12866 THE FEAST OF SAINT POLYCARP, BISHOP & MARTYR 23 FEBRUARY 2019 11:00A.M. Preface to the Ordination Rites The Holy Scriptures and ancient Christian writers make it clear that from the apostles’ time, there have been different ministries within the Church. In particular, since the time of the New Testament, three distinct orders of ordained ministers have been characteristic of Christ’s holy catholic Church. First, there is the order of bishops who carry on the apostolic work of leading, supervising, and uniting the Church. Secondly, associated with them are the presbyters, or ordained elders, in subsequent times generally known as priests. Together with the bishops, they take part in the governance of the Church, in the carrying out of its missionary and pastoral work, and in the preaching of the Word of God and administering his holy Sacraments. Thirdly, there are deacons who assist bishops and priests in all of this work. It is also a special responsibility of deacons to minister in Christ’s name to the poor, the sick, the suffering, and the helpless. The persons who are chosen and recognized by the Church as being called by God to the ordained ministry are admitted to these sacred orders by solemn prayer and the laying on of episcopal hands. It has been, and is, the intention and purpose of this Church to maintain and continue these three orders; and for this purpose these services of ordination and consecration are appointed. No persons are allowed to exercise the offices of bishop, priest, or deacon in this Church unless they are so ordained, or have already received such ordination with the laying on of hands by bishops who are themselves duly qualified to confer Holy Orders. -

CHRISTUS DOMINUS Decree Concerning the Pastoral Office of Bishops in the Church

CHRISTUS DOMINUS Decree Concerning the Pastoral Office of Bishops in the Church Petru GHERGHEL*1 I am pleased to participate, although not in person, in this academic meeting organized by the Roman-Catholic Theological Institute of Iasi and the Faculty of Roman-Catholic Theology within the Al. I. Cuza University, and I take this opportunity to express to the rector Fr. Benone Lucaci, PhD, organizer of this symposium, to Fr. Stefan Lupu, PhD, to the fathers associ- ate professors, seminarians, guests and to all participants, a warm welcome accompanied by a wish for heavenly blessing and for distinguished achieve- ments in the mission to continue the analysis of the great Second Vatican Council and to share to all believers, but not only, the richness of the holy teachings developed with a true spirit of faith by the Council Fathers under the coordination of the Holy Father, Saint John XXIII and Blessed Paul VI. It is a happy moment to relive that event and it is a real joy to have the opportunity to go back in time and rediscover the great values that the Christian people, and not only, received from the great Second Vatican Council, from the celebration of which we mark 50 years this year. Among the documents, which remain as a true legacy in the treasure of the Church and that the Second Vatican Council had included on its agenda for particular study and deepening, a special attention was devoted to the reflection on the ministry of bishops as successors of the Apostles and Pas- tors of Christian people in close communion with the Holy Father, the Pope, the successor of St. -

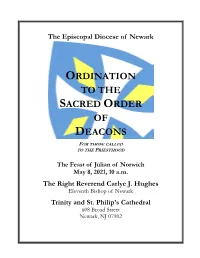

Ordination to the Sacred Order of Deacons

The Episcopal Diocese of Newark ORDINATION TO THE SACRED ORDER OF DEACONS FOR THOSE CALLED TO THE PRIESTHOOD The Feast of Julian of Norwich May 8, 2021, 10 a.m. The Right Reverend Carlye J. Hughes Eleventh Bishop of Newark Trinity and St. Philip’s Cathedral 608 Broad Street Newark, NJ 07102 MINISTERS OF THE LITURGY Celebrant The Right Reverend Carlye J. Hughes, Eleventh Bishop of Newark Minister of Ceremonies and Litanist The Reverend Canon Andrew Wright, Canon to the Ordinary Lector Ms. Gail Barkley, Trinity and St. Philip’s Cathedral Gospeller The Rev. Deacon Ken Boccino, Church of the Saviour, Denville Preacher The Reverend Thomas M. Murphy, St. Paul and Incarnation, Jersey City Deacons of the Table The Newly Ordained Soloist Ms. Gail Blache-Gill, St. Paul and Incarnation, Jersey City Organist Mr. Mark Trautman, St. Paul’s, Englewood; Missioner for Music and the Arts Altar Guild Ms. Gail Barkley and the People of Trinity and St. Philip’s Cathedral 2 Preface to the Ordination Rites The Holy Scriptures and ancient Christian writers make it clear that from the apostles’ time, there have been different ministries within the Church. In particular, since the time of the New Testament, three distinct orders of ordained ministers have been characteristic of Christ’s holy Catholic Church. First, there is the order of bishops who carry on the apostolic work of leading, supervising, and uniting the Church. Secondly, associated with them are the presbyters, or ordained elders, in subsequent times generally known as priests. Together with the bishops, they take part in the governance of the Church, in the carrying out of its missionary and pastoral work, and in the preaching of the Word of God and administering his holy Sacraments. -

Pdf (Accessed January 21, 2011)

Notes Introduction 1. Moon, a Presbyterian from North Korea, founded the Holy Spirit Association for the Unification of World Christianity in Korea on May 1, 1954. 2. Benedict XVI, post- synodal apostolic exhortation Saramen- tum Caritatis (February 22, 2007), http://www.vatican.va/holy _father/benedict_xvi/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_ben-xvi _exh_20070222_sacramentum-caritatis_en.html (accessed January 26, 2011). 3. Patrician Friesen, Rose Hudson, and Elsie McGrath were subjects of a formal decree of excommunication by Archbishop Burke, now a Cardinal Prefect of the Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signa- tura (the Roman Catholic Church’s Supreme Court). Burke left St. Louis nearly immediately following his actions. See St. Louis Review, “Declaration of Excommunication of Patricia Friesen, Rose Hud- son, and Elsie McGrath,” March 12, 2008, http://stlouisreview .com/article/2008-03-12/declaration-0 (accessed February 8, 2011). Part I 1. S. L. Hansen, “Vatican Affirms Excommunication of Call to Action Members in Lincoln,” Catholic News Service (December 8, 2006), http://www.catholicnews.com/data/stories/cns/0606995.htm (accessed November 2, 2010). 2. Weakland had previously served in Rome as fifth Abbot Primate of the Benedictine Confederation (1967– 1977) and is now retired. See Rembert G. Weakland, A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church: Memoirs of a Catholic Archbishop (Grand Rapids, MI: W. B. Eerdmans, 2009). 3. Facts are from Bruskewitz’s curriculum vitae at http://www .dioceseoflincoln.org/Archives/about_curriculum-vitae.aspx (accessed February 10, 2011). 138 Notes to pages 4– 6 4. The office is now called Vicar General. 5. His principal consecrator was the late Daniel E. Sheehan, then Arch- bishop of Omaha; his co- consecrators were the late Leo J. -

Catechism-Of-The-Catholic-Church.Pdf

CATECHISM OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH Table of Contents PROLOGUE I. The life of man - to know and love God nn. 1-3 II. Handing on the Faith: Catechesis nn. 4-10 III. The Aim and Intended Readership of the Catechism nn. 11-12 IV. Structure of this Catechism nn. 13-17 V. Practical Directions for Using this Catechism nn. 18-22 VI. Necessary Adaptations nn. 23-25 PART ONE: THE PROFESSION OF FAITH SECTION ONE "I BELIEVE" - "WE BELIEVE" n. 26 CHAPTER ONE MAN'S CAPACITY FOR GOD nn. 27-49 I. The Desire for God nn. 27-30 II. Ways of Coming to Know God nn. 31-35 III. The Knowledge of God According to the Church nn. 36-38 IV. How Can We Speak about God? nn.39-43 IN BRIEF nn. 44-49 CHAPTER TWO GOD COMES TO MEET MAN n. 50 Article 1 THE REVELATION OF GOD I. God Reveals His "Plan of Loving Goodness" nn. 51-53 II. The Stages of Revelation nn. 54-64 III. Christ Jesus -- "Mediator and Fullness of All Revelation" nn. 65- 67 IN BRIEF nn. 68-73 Article 2 THE TRANSMISSION OF DIVINE REVELATION n. 74 I. The Apostolic Tradition nn.75-79 II. The Relationship Between Tradition and Sacred Scripture nn. 80-83 III. The Interpretation of the Heritage of Faith nn. 84-95 IN BRIEF nn. 96-100 Article 3 SACRED SCRIPTURE I. Christ - The Unique Word of Sacred Scripture nn. 101-104 II. Inspiration and Truth of Sacred Scripture nn. 105-108 III. The Holy Spirit, Interpreter of Scripture nn. -

Keys to the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy

3 Keys to the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy September 2013 This document: SECOND VATICAN COUNCIL, Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy [CSL], Sacrosanctum concilium [SC], 4 December 1963, was a watershed for the Catholic Church and the Christian world. It was the first document of the Council and was issued toward the end of the second session. This constitution sets out the reform of the Liturgy, the liturgical books, and the very life of the Church. In the 50 years since this Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy was promulgated by Pope Paul VI, many authors have written about it and its impact on Church life. These pages highlight some worthy resources and worthy writing. For each work, there is the usual bibliographic information, a publisher link, recommended uses, and a synopsis. There is also a list of KEYS TO THE CONSTITUTION ON THE SACRED LITURGY from each author’s perspective. There are differences and overlaps in these lists. But these Keys will provide valuable summaries for study, for formation, for assessment, and for the ongoing work of the liturgical reform. For questions and other help, contact: Eliot Kapitan, director [email protected] or (217) 698-8500 ext. 177 Diocese of Springfield in Illinois Catholic Pastoral Center ♦ 1615 West Washington Street ♦ Springfield IL 62702-4757 (217) 698-8500 ♦ FAX (217) 698-0802 ♦ WEB www.dio.org Office for Worship and the Catechumenate E-MAIL [email protected] Funded by generous contributions to the Annual Catholic Services Appeal. ♦♦♦ CONTENTS & BIBLIOGRAPHY ♦♦♦ ♦♦♦ CONSTITUTION ON THE SACRED LITURGY ♦♦♦ Page 04 Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy Editions Page 05 Outline of the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy ♦♦♦ RESOURCES ON THE CSL ♦♦♦ Page 06 A Pastoral Commentary on Sacrosanctum Concilium: The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy of the Second Vatican Council. -

A Reflection on the Decree on the Apostolate of the Laity from the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965)

A Reflection on the Decree on the Apostolate of the Laity from the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) We at the Second Vatican Council make an earnest appeal to all the laypeople of the Church. We ask that you make a willing, noble, and enthusiastic response to God’s call. Christ is calling you indeed! The Spirit is urging you. You who are in the younger generation: you, too, are being called! Welcome this call with an eager heart and a generous spirit. It is the Lord, through this council, who is once more inviting all Christians of every level of the Church to work diligently in the harvest. Join yourselves to the mission of Christ in the world, knowing that in the Lord, your labors will not be lost. (Article 33) DOCUMENTS OF VATICAN II (1962-1965) Council documents are written first in Latin and so have an “official” Latin title (taken from the first words of the document). What has become the English translation of the documents’ titles follows in parenthesis. CONSTITUTIONS Constitutions are the most solemn and formal type of document issued by an ecumenical council. They treat substantive doctrinal issues that pertain to the “very nature of the church.” Sacrosanctum concilium (Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy) Dei Verbum (Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation) Lumen Gentium (Dogmatic Constitution on the Church) Gaudium et Spes (Pastoral Constitution on the Church In the Modern World) DECREES Draw on the doctrinal principles focused on in the Constitutions and applies them to specific issues or groups in the Church. Christus -

1965 Decree Christus Dominus Concerning the Pastoral Office Of

1965 Decree Christus Dominus Concerning the Pastoral Office of Bishops in the Church Vatican Council II (Excerpts) 28 October 1965 6. As legitimate successors of the Apostles and members of the episcopal college, [229] bishops should realize that they are bound together and should manifest a concern for all the churches. For by divine institution and the rule of the apostolic office each one together with all the other bishops is responsible for the Church.7 They should especially be concerned about those parts of the world where the word of God has not yet been proclaimed or where the faithful, particularly because of the small number of priests, are in danger of departing from the precepts of the Christian life, and even of losing the faith itself. Let bishops, therefore, make every effort to have the faithful actively support and [230] promote works of evangelization and the apostolate. Let them strive, moreover, to see to it that suitable sacred ministers as well as auxiliaries, both religious and lay, be prepared for the missions and other areas suffering from a lack of clergy. They should also see to it, as much as possible, that some of their own priests go to the above-mentioned missions or dioceses to exercise the sacred ministry there either permanently or for a set period of time. Bishops should also be mindful, in administering ecclesiastical property, of the [231] needs not only of their own dioceses but also of the other particular churches, for they are also a part of the one Church of Christ. -

May This Work Begin, Continue, and Be Brought to Fulfillment in Him

may this work begin, continue, and be brought to fulfillment in him. A Parish of the Diocese of Boise Dear Brothers and Sisters in Christ, The dream has become a reality; the vision is now visible; our hope has been fulfilled. As we gather together to dedicate Risen Christ Catholic Church we remember the prayers, the hard work, and the sacrifices given to bring this to fruition. We gather as a community united in Christ and in spirit to dedicate this church that we may worship, celebrate the sacraments and serve one another. As your bishop, I offer my gratitude to you for the gifts of your time, talent and treasure that enables us to dedicate this church today, for the future of the Risen Christ Catholic Community. Praying God’s continued blessings upon you, I remain, Sincerely yours in Christ, John Taye, sculptor Fr. Joseph da Silva blesses the foundation stone while Members of the Building Planning of the tabernacle, Deacon Michael Eisenbeiss looks on. Another intention is added to the wall Committee meet with Fr. Mark processional cross, at the foundation stone dedication. Joseph Costello. and paschal candle. Most Reverand Michael P. Driscoll, MSW, DD Bishop of Boise a r t i s t s Dear Friends, b u i l d i n g p l a n n i n g John Taye received a BFA from the University of Utah and an MFA from Otis Art Institute of Los c o m m i t t e e The Catholic imagination alerts us to the presence of God — everywhere. -

Catechism of the Catholic Church Second Edition

10174 Old Grove Road, Suite 200, San Diego, CA 92131 858-653-6740 www.JPCatholic.com CATECHISM OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH SECOND EDITION PART ONE THE PROFESSION OF FAITH SECTION TWO THE PROFESSION OF THE CHRISTIAN FAITH CHAPTER THREE I BELIEVE IN THE HOLY SPIRIT ARTICLE 9 "I BELIEVE IN THE HOLY CATHOLIC CHURCH" Paragraph 2. The Church - People of God, Body of Christ, Temple of the Holy Spirit I. THE CHURCH - PEOPLE OF GOD 781 "At all times and in every race, anyone who fears God and does what is right has been acceptable to him. He has, however, willed to make men holy and save them, not as individuals without any bond or link between them, but rather to make them into a people who might acknowledge him and serve him in holiness. He therefore chose the Israelite race to be his own people and established a covenant with it. He gradually instructed this people. All these things, however, happened as a preparation for and figure of that new and perfect covenant which was to be ratified in Christ . the New Covenant in his blood; he called together a race made up of Jews and Gentiles which would be one, not according to the flesh, but in the Spirit."201 Characteristics of the People of God 782 The People of God is marked by characteristics that clearly distinguish it from all other religious, ethnic, political, or cultural groups found in history: - It is the People of God: God is not the property of any one people. But he acquired a people for himself from those who previously were not a people: "a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation."202 - One becomes a member of this people not by a physical birth, but by being "born anew," a birth "of water and the Spirit,"203 that is, by faith in Christ, and Baptism.