NAGPRA Consultation and the National Park Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 2019 Competitive Oil and Gas Lease Sale Monticello Field Office DOI-BLM-UT-0000-2019-0003-OTHER NEPA -Mtfo-EA

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management July 2019 September 2019 Competitive Oil and Gas Lease Sale Monticello Field Office DOI-BLM-UT-0000-2019-0003-OTHER NEPA -MtFO-EA Monticello Field Office 365 North Main PO Box 7 Monticello, UT 84535 DOI-BLM-UT-0000-2019-0003_Other NEPA-MtFO-EA July 2019 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Purpose & Need .................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Project Location and Legal Description ........................................................................................ 4 1.2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Background ................................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Purpose and Need ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.5 Decision to be Made ..................................................................................................................... 6 1.6 Plan Conformance Review............................................................................................................ 6 1.7 Relationship to Statutes, Regulations, Policies or Other Plans ..................................................... 9 1.8 Issues Identified ......................................................................................................................... -

People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: a Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada

Portland State University PDXScholar Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations Anthropology 2012 People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: A Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada Douglas Deur Portland State University, [email protected] Deborah Confer University of Washington Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Deur, Douglas and Confer, Deborah, "People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: A Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada" (2012). Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations. 98. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac/98 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Pacific West Region: Social Science Series National Park Service Publication Number 2012-01 U.S. Department of the Interior PEOPLE OF SNOWY MOUNTAIN, PEOPLE OF THE RIVER: A MULTI-AGENCY ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW AND COMPENDIUM RELATING TO TRIBES ASSOCIATED WITH CLARK COUNTY, NEVADA 2012 Douglas Deur, Ph.D. and Deborah Confer LAKE MEAD AND BLACK CANYON Doc Searls Photo, Courtesy Wikimedia Commons -

Tribal Higher Education Contacts.Pdf

New Mexico Tribes/Pueblos Mescalero Apache Contact Person: Kelton Starr Acoma Pueblo Address: PO Box 277, Mescalero, NM 88340 Phone: (575) 464-4500 Contact Person: Lloyd Tortalita Fax: (575) 464-4508 Address: PO Box 307, Acoma, NM 87034 Phone: (505) 552-5121 Fax: (505) 552-6812 Nambe Pueblo E-mail: [email protected] Contact Person: Claudene Romero Address: RR 1 Box 117BB, Santa Fe, NM 87506 Cochiti Pueblo Phone: (505) 455-2036 ext. 126 Fax: (505) 455-2038 Contact Person: Curtis Chavez Address: 255 Cochiti St., Cochiti Pueblo, NM 87072 Phone: (505) 465-3115 Navajo Nation Fax: (505) 465-1135 Address: ONNSFA-Crownpoint Agency E-mail: [email protected] PO Box 1080,Crownpoint, NM 87313 Toll Free: (866) 254-9913 Eight Northern Pueblos Council Fax Number: (505) 786-2178 Email: [email protected] Contact Person: Rob Corabi Website: http://www.onnsfa.org/Home.aspx Address: 19 Industrial Park Rd. #3, Santa Fe, NM 87506 (other ONNSFA agency addresses may be found on the Phone: (505) 747-1593 website) Fax: (505) 455-1805 Ohkay Owingeh Isleta Pueblo Contact Person: Patricia Archuleta Contact Person: Jennifer Padilla Address: PO Box 1269, Ohkay Owingeh, NM 87566 Address: PO Box 1270, Isleta,NM 87022 Phone: (505) 852-2154 Phone: (505) 869-9720 Fax: (505) 852-3030 Fax: (505) 869-7573 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.isletapueblo.com Picuris Pueblo Contact Person: Yesca Sullivan Jemez Pueblo Address: PO Box 127, Penasco, NM 87553 Contact Person: Odessa Waquiu Phone: (575) 587-2519 Address: PO Box 100, Jemez Pueblo, -

NEW MEXICO, SANTA FE New Mexico State Records Center And

Guide to Catholic-Related Records in the West about Native Americans See User Guide for help on interpreting entries NEW MEXICO, SANTA FE new 2006 New Mexico State Records Center and Archives W-382 1205 Camino Carlos Rey Santa Fe, New Mexico 87507 Phone 505-476-7948 http://www.nmcpr.state.nm.us/ Online Archive of New Mexico, http://elibrary.unm.edu/oanm/ Hours: Monday-Friday, 8:00-4:45 Access: Some restrictions apply Copying facilities: Yes Holdings of Catholic-related records about Native Americans: Inclusive dates: 1598-present; n.d. Volume: 1-2 cubic feet Description: 26 collections include Native Catholic records. /1 “Valentin Armijo Collection, 1960-002” Inclusive dates: Between 1831-1883 Volume: Less than .2 cubic foot Description: Papers (copies) of Valentin Armijo; includes the Catholic Church in Peña Blanca, New Mexico. /2 “Alice Scoville Barry Collection of Historical Documents, 1959-016” Inclusive dates: 1791, 1799, 1826 Volume: 3 folders Description: Finding aid online, http://elibrary.unm.edu/oanm/; includes: a. “Letter Comandante General Pedro de Nava, Chihuahua, to Governor of New Mexico Fernando de la Concha,” July 26, 1791, 1 letter: re: death of Father Francisco Martin-Bueno, O.F.M., the scarcity of ministers, and the substitution of Fray Francisco Ocio, O.F.M. to administer to the Pueblos of Pecos and Tesuque b. “Letter from Comandante General Pedro de Nava, Chihuahua, to governor of New Mexico,” August 6, 1799, 1 letter: re: religion c. “Letter from Baltazar Perea, Bernalillo, to the Gefe Politico y Militar [Governor],” July 2, 1826, 1 letter: re: construction of a chapel at Bernalillo /3 “Fray Angelico Chavez Collection of New Mexico Historical Documents, 1960- 007” Inclusive dates: 1678-1913 (bulk, 1689-1811) Volume: Approximately .3 cubic foot 1 Description: Includes the missions at Zuni Pueblo, San Ildefonso Pueblo, Laguna Pueblo, and Santa Cruz, New Mexico. -

Southern Sinagua Sites Tour: Montezuma Castle, Montezuma

Information as of Old Pueblo Archaeology Center Presents: March 4, 2021 99 a.m.-5:30a.m.-5:30 p.m.p.m. SouthernSouthern SinaguaSinagua SitesSites Tour:Tour: MayMay 8,8, 20212021 MontezumaMontezuma Castle,Castle, SaturdaySaturday MontezumaMontezuma Well,Well, andand TuzigootTuzigoot $30 donation ($24 for members of Old Pueblo Archaeology Center or Friends of Pueblo Grande Museum) Donations are due 10 days after reservation request or by 5 p.m. Wednesday May 8, whichever is earlier. SEE NEXT PAGES FOR DETAILS. National Park Service photographs: Upper, Tuzigoot Pueblo near Clarkdale, Arizona Middle and lower, Montezuma Well and Montezuma Castle cliff dwelling, Camp Verde, Arizona 9 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Saturday May 8: Southern Sinagua Sites Tour – Montezuma Castle, Montezuma Well, and Tuzigoot meets at Montezuma Castle National Monument, 2800 Montezuma Castle Rd., Camp Verde, Arizona What is Sinagua? Named with the Spanish term sin agua (‘without water’), people of the Sinagua culture inhabited Arizona’s Middle Verde Valley and Flagstaff areas from about 6001400 CE Verde Valley cliff houses below the rim of Montezuma Well and grew corn, beans, and squash in scattered lo- cations. Their architecture included masonry-lined pithouses, surface pueblos, and cliff dwellings. Their pottery included some black-on-white ceramic vessels much like those produced elsewhere by the An- cestral Pueblo people but was mostly plain brown, and made using the paddle-and-anvil technique. Was Sinagua a separate culture from the sur- rounding Ancestral Pueblo, Mogollon, Hohokam, and Patayan ones? Was Sinagua a branch of one of those other cultures? Or was it a complex blending or borrowing of attributes from all of the surrounding cultures? Whatever the case might have been, today’s Hopi Indians consider the Sinagua to be ancestral to the Hopi. -

Passage and Discovery: the Southwest Studies Major

Non-Profit Org. U.S. Postage PAID Colorado Springs, CO 14 East Cache La Poudre Street Permit No. 105 Colorado Springs, CO 80903 Vol. XVIII, No. 3 Fall 2002 Passage and Discovery: The Southwest Studies Major Tracey Clark, Southwest Studies Major (’03), Colorado Springs, CO Early June, and I’m headed south from Taos, New Mexico, into a context that has remained with me to this day. That class toward Santa Fe. It is day one of a seven-day research trip into lit the spark that would later result in my decision to major in the heart of the Southwest. The morning sunlight cuts a clear Southwest Studies. I would not make that decision for another path to the western horizon, illuminating the gaping mouth of year and a half, after first declaring myself an art history major. I the Rio Grande gorge. This sight never fails to inspire me. With am grateful that I have developed a firm foundation in art history awe and anticipation, I wonder what awaits me on this journey. because I feel that it strengthens my studies now and will be a I am a fourth-year non-traditional student at Colorado benefit when I continue on to graduate school. College and a Liberal Arts and Sciences major with an emphasis Being a Southwest Studies major has allowed me the flexibility in Southwest Studies. My focus of study is Art and Culture of the and freedom to define my own interests and choose my classes Fall 2002 Southwest, specifically pottery of the Pueblo people. -

11. References

11. References Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT). State Transportation Improvement Program. December 1994. Associated Cultural Resource Experts (ACRE). Boulder City/U.S. 93 Corridor Study Historic Structures Survey. Vol. 1: Final Report. September 2002. _______________. Boulder City/U.S. 93 Corridor Study Historic Structures Survey. Vol. 1: Technical Report. July 2001. Averett, Walter. Directory of Southern Nevada Place Names. Las Vegas. 1963. Bedwell, S. F. Fort Rock Basin: Prehistory and Environment. University of Oregon Books, Eugene, Oregon. 1973. _______________. Prehistory and Environment of the Pluvial Fort Rock Lake Area of South Central Oregon. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon, Eugene. 1970. Bernard, Mary. Boulder Beach Utility Line Installation. LAME 79C. 1979. Bettinger, Robert L. and Martin A. Baumhoff. The Numic Spread: Great Basin Cultures in Competition. American Antiquity 46(3):485-503. 1982. Blair, Lynda M. An Evaluation of Eighteen Historic Transmission Line Systems That Originate From Hoover Dam, Clark County, Nevada. Harry Reid Center for Environmental Studies, Marjorie Barrick Museum of Natural History, University of Nevada, Las Vegas. 1994. _______________. A New Interpretation of Archaeological Features in the California Wash Region of Southern Nevada. M.A. Thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Nevada, Las Vegas. 1986. _______________. Virgin Anasazi Turquoise Extraction and Trade. Paper presented at the 1985 Arizona-Nevada Academy of Sciences, Las Vegas, Nevada. 1985. Blair, Lynda M. and Megan Fuller-Murillo. Rock Circles of Southern Nevada and Adjacent Portions of the Mojave Desert. Harry Reid Center for Environmental Studies, University of Nevada, Las Vegas. HRC Report 2-1-29. 1997. Blair, Lynda M. -

Texas Archeological and Paleontological Society

BULLETIN OF THE Texas Archeological and Paleontological Society Volume Nine SEPTEMBER 1937 Published by the Society at Abilene, Texas COPYRIGHT, 1937 BY TEXAS ARCHEOLOGICAL AND PALEONTOLOGICAL SOCIETY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA The Texas Archeological and Paleontological Society OFFICERS CYRUS N. RAY, President JULIUS OLSEN, Vice-President OTTO O. WATTS, Secretary-Treasurer DIRECTORS CYRUS N. RAY, D.O. W. C. HOLDEN, Ph. D. JULIUS OLSEN, Ph D., Sc.D. RUPERT RICHARDSON, Ph. D. OTTO O. WATTS, Ph. D. C. W. HANLEY REGIONAL VICE-PRESIDENTS FLOYD V. S TUDER - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Amarillo COL. M. L. CRIMMINS - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - New York, N. Y. VICTOR J. SMITH - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Alpine C. L. WEST - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Hamilton DR. J. E. PEARCE - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Austin LESTER B. WOOD - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Breckenridge JUDGE O. L. SIMS - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Paint Rock TRUSTEES DR. ELLIS SHULER - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Dallas DR. STEWART COOPER - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Abilene W. A. RINEY - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Abilene PRICE CAMPBELL - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Abilene FRED COCKRELL - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Abilene ERNEST W. W ILSON - -

Fact Sheet Overview

southwestlearning.org MONTEZUMA WELL Montezuma Well FACTOVERVIEW SHEET CO 1864 - Present W AN (2012:FIGURE 7) Montezuma Well, long the home of prehistoric Hohokam, Sinagua, Yavapai, and Apache people, was, following the establishment of Arizona Territory in 1863, a working cattle ranch and one of Arizona’s first tourist attractions before be- ing acquired by the National Park Service in 1947. The Well itself passed through a series of owners between 1883 and 1888, when William and Margorie Back bought the squat- ters claim for the land and filed for a homestead. Over the next 60 years, two generations of the Back family operated the Well ranch and museum. History of Land Use Although most likely encountered by Spanish explorers in the William “Bill” Beriman Back sitting on the porch of the original Back Fam- late 1500s, Montezuma Well was not officially re-discovered ily home. Original image courtesy of Helen Cain. until 1864, when it acquired the name “Montezuma” from a party venturing forth from Fort Whipple, a military establish- diverting water from both Wet Beaver Creek and Montezuma ment some 50 miles west. These early visitors noted not only Well to irrigate 30 acres of their holdings, which they oper- the deep water of the Well itself, but also the prehistoric dwell- ated as a mail station and support post supplying hay and veg- ings in and around the Well, and the prehistoric irrigation ditch etables to the local military post and feed and range space for later reclaimed and used by the first settlers (this ditch trans- the horses and mules of the express riders, freight wagons, and ports Well water to residents of the Verde Valley to this day). -

Exchange As an Adaptive Strategy in Southern Nevada

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 12-1-2014 Keeping in Touch: Exchange as an Adaptive Strategy in Southern Nevada Timothy Joshua Ferguson University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, and the Chemistry Commons Repository Citation Ferguson, Timothy Joshua, "Keeping in Touch: Exchange as an Adaptive Strategy in Southern Nevada" (2014). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2258. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/7048577 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KEEPING IN TOUCH: EXCHANGE AS AN ADAPTIVE STRATEGY IN SOUTHERN NEVADA By Timothy J. Ferguson Bachelor of Arts in Art History and Archaeology University of Missouri - Columbia 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts -- Anthropology Department of Anthropology College of Liberal Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2014 We recommend the thesis prepared under our supervision by Timothy J. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT of COLUMBIA PUEBLO of ACOMA ) 25 Pinsbaari Drive ) Acoma Pueblo, NM 87034 ) )

Case 1:21-cv-00253-BAH Document 1 Filed 01/28/21 Page 1 of 16 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA PUEBLO OF ACOMA ) 25 Pinsbaari Drive ) Acoma Pueblo, NM 87034 ) ) ) PLAINTIFF, ) ) v. ) ) NORRIS COCHRAN, in his official capacity ) as Acting Secretary, ) U.S. Department of Health & Human Services ) 200 Independence Avenue, S.W. ) Civil Action No. 21- Washington, D.C. 20201 ) ) DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND ) HUMAN SERVICES ) 200 Independence Avenue, S.W. ) Washington, D.C. 20201 ) ) ELIZABETH FOWLER, in her official capacity ) as Acting Director, ) Indian Health Service ) 5006 Fisher's Lane ) COMPLAINT Rockville, MD 20857 ) ) INDIAN HEALTH SERVICE ) 5006 Fisher's Lane ) Rockville, MD 20857 ) ) DEFENDANTS. ) COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF Plaintiff Acoma Pueblo (“Tribe”), a federally recognized tribe, for its causes of actions against the Defendants named above, alleges as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. The Tribe brings this action against the Department of Health and Human Services Case 1:21-cv-00253-BAH Document 1 Filed 01/28/21 Page 2 of 16 ("HHS") and its agency, the Indian Health Service ("IHS"), seeking redress for their decision to close the Acoma- Cañoncito -Laguna Hospital ("ACL Hospital") without providing Congress the requisite evaluation and one year notice required by Section 301(b) of the Indian Health Care Improvement Act ("IHCIA"), 25 U.S.C. §1631(b) and determination required by Section 105(i) of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act ("ISDEAA"), 25 U.S.C. § 5324(i). According to the IHS, it intends to cease operating ACL Hospital as a hospital on February 1, 2021 and instead begin operating the facility as an urgent care facility with limited hours and no capacity to provide inpatient or emergency room services. -

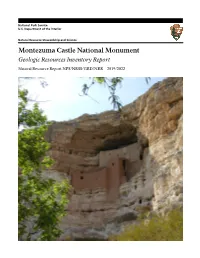

Montezuma Castle National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Montezuma Castle National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2019/2022 ON THE COVER Photograph of Montezuma Castle (cliff dwellings). Early in the 12th century, ancestral Native American people called the “Southern Sinagua” by archeologists began building a five-story, 20-room dwelling in an alcove about 30 m (100 ft) above the valley floor. The alcove occurs in the Verde Formation, limestone. The contrast of two colors of mortar is evident in this photograph. More than 700 years ago, inhabitants applied the lighter white mortar on the top one-third. In the late 1990s, the National Park Service applied the darker red mortar on the bottom two-thirds. Photograph by Katie KellerLynn (Colorado State University). THIS PAGE Photograph of Montezuma Castle National Monument. View is looking west from the top of the Montezuma Castle ruins. Beaver Creek, which flows through the Castle Unit of the monument, is on the valley floor. NPS photograph available at https://www.nps.gov/moca/learn/photosmultimedia/ photogallery.htm (accessed 22 November 2017). Montezuma Castle National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2019/2022 Katie KellerLynn Colorado State University Research Associate National Park Service Geologic Resources Inventory Geologic Resources Division PO Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225 October 2019 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics.