The First Neuroethics Meeting: Then and Now Essays by Jonathan D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haecceitism, Chance

HAECCEITISM, CHANCE, AND COUNTERFACTUALS Boris Kment Abstract. Anti-haecceitists believe that all facts about specific individuals—such as the fact that Fred exists, or that Katie is tall—globally supervene on purely qualitative facts. Haecceitists deny that. The issue is not only of interest in itself, but receives additional importance from its intimate connection to the question of whether all fundamental facts are qualitative or whether they include facts about which specific individuals there are and how qualitative properties and relations are distributed over them. Those who think that all fundamental facts are qualitative are arguably committed to anti-haecceitism. The goal of this paper is to point out some problems for anti-haecceitism (and therefore for the thesis that all fundamental facts are qualitative). The article focuses on two common assumptions about possible worlds: (i) Sets of possible worlds are the bearers of objective physical chance. (ii) Counterfactual conditionals can be defined by appeal to a relation of closeness between possible worlds. The essay tries to show that absurd consequences ensue if either of these assumptions is combined with anti-haecceitism. Then it considers a natural response by the anti-haecceitist, which is to deny that worlds play the role described in (i) and (ii). Instead, the reply continues, we can introduce a new set of entities that are defined in terms of worlds and that behave the way worlds do on the haecceitist position. That allows the anti-haecceitist to formulate anti-haecceitist friendly versions of (i) and (ii) by replacing the appeal to possible worlds with reference to the newly introduced entities. -

Neurophilosophy and Its Discontents How Do We Understand Consciousness Without Becoming Complicit in That Understanding?

Neurophilosophy and Its Discontents How Do We Understand Consciousness Without Becoming Complicit in that Understanding? BY GABRIELLE BENETTE JACKSON dependent on empathy or imagination. Though presumably it would not capture everything, its goal would be to describe, at least in part, the subjective character of hat is consciousness? “It is being awake,” “being responsive,” “acting,” “being experience in a form comprehensible to beings incapable of having those experi- Waware,” “being self-aware,” “paying attention,” “perceiving,” “feeling emo- ences. […] It should be possible to devise a method of expressing in objective terms tions,” “feeling feelings,” “having thoughts,” “thinking about thoughts,” “it is like much more than we can at present, and with much greater precision.” The proposal, this!” simply put, was to develop a language to describe subjectivity in non-subjective Who is conscious? “We humans, surely!” Well, maybe not all the time. “Animals!” terms. And although it is definitely not the case that all theorists pushing past the Debatable. “Computers?” No—at least, not yet. “Other machines?” Only in fiction. problem of consciousness consider themselves to be implementing Nagel’s plan, it “Plants?” Absolutely not, right? does help to understand a particular set of accumulated answers. Two fundamental Nearly twenty-five years ago, we lived through “the project of the decade of the approaches have been neurophilosophy and neurophenomenology, each emphasizing brain,” a governmental initiative set forth by President one aspect of Nagel’s suggestion—either the objective part George H. W. Bush.1 Presidential Proclamation 6158 (viz. neurophilosophy) or the phenomenology part (viz. begins, “The human brain, a three-pound mass of inter- neurophenomenology). -

Churchland Source: the Journal of Philosophy, Vol

Journal of Philosophy, Inc. Reduction, Qualia, and the Direct Introspection of Brain States Author(s): Paul M. Churchland Source: The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 82, No. 1 (Jan., 1985), pp. 8-28 Published by: Journal of Philosophy, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2026509 Accessed: 07-08-2015 19:14 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Philosophy, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Philosophy. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.58.129.109 on Fri, 07 Aug 2015 19:14:45 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 8 THE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY structureof this idiom, moreover-its embeddingof a subordinate sentence-would have been clearly dictatedby its primitiveuse in assessing children's acquisition of observationsentences. Analogi- cal extension of the idiom to other than observation sentences would follow inevitably,and the developmentof parallel idioms for other propositional attitudeswould then come naturally too, notwithstanding their opacity from a logical point of view. Naturalness is one thing, transparencyanother; familiarityone, clarityanother. W. V. QtJINE Harvard University REDUCTION, QUALIA, AND THE DIRECT INTROSPECTION OF BRAIN STATES* DO the phenomenological or qualitative featuresof our sen- sations constitutea permanentbarrier to thereductive aspi- rations of any materialisticneuroscience? I here argue that theydo not. -

Distance Learning Program Anatomy of the Human Brain/Sheep Brain Dissection

Distance Learning Program Anatomy of the Human Brain/Sheep Brain Dissection This guide is for middle and high school students participating in AIMS Anatomy of the Human Brain and Sheep Brain Dissections. Programs will be presented by an AIMS Anatomy Specialist. In this activity students will become more familiar with the anatomical structures of the human brain by observing, studying, and examining human specimens. The primary focus is on the anatomy, function, and pathology. Those students participating in Sheep Brain Dissections will have the opportunity to dissect and compare anatomical structures. At the end of this document, you will find anatomical diagrams, vocabulary review, and pre/post tests for your students. The following topics will be covered: 1. The neurons and supporting cells of the nervous system 2. Organization of the nervous system (the central and peripheral nervous systems) 4. Protective coverings of the brain 5. Brain Anatomy, including cerebral hemispheres, cerebellum and brain stem 6. Spinal Cord Anatomy 7. Cranial and spinal nerves Objectives: The student will be able to: 1. Define the selected terms associated with the human brain and spinal cord; 2. Identify the protective structures of the brain; 3. Identify the four lobes of the brain; 4. Explain the correlation between brain surface area, structure and brain function. 5. Discuss common neurological disorders and treatments. 6. Describe the effects of drug and alcohol on the brain. 7. Correctly label a diagram of the human brain National Science Education -

In Defence of Folk Psychology

FRANK JACKSON & PHILIP PETTIT IN DEFENCE OF FOLK PSYCHOLOGY (Received 14 October, 1988) It turned out that there was no phlogiston, no caloric fluid, and no luminiferous ether. Might it turn out that there are no beliefs and desires? Patricia and Paul Churchland say yes. ~ We say no. In part one we give our positive argument for the existence of beliefs and desires, and in part two we offer a diagnosis of what has misled the Church- lands into holding that it might very well turn out that there are no beliefs and desires. 1. THE EXISTENCE OF BELIEFS AND DESIRES 1.1. Our Strategy Eliminativists do not insist that it is certain as of now that there are no beliefs and desires. They insist that it might very well turn out that there are no beliefs and desires. Thus, in order to engage with their position, we need to provide a case for beliefs and desires which, in addition to being a strong one given what we now know, is one which is peculiarly unlikely to be undermined by future progress in neuroscience. Our first step towards providing such a case is to observe that the question of the existence of beliefs and desires as conceived in folk psychology can be divided into two questions. There exist beliefs and desires if there exist creatures with states truly describable as states of believing that such-and-such or desiring that so-and-so. Our question, then, can be divided into two questions. First, what is it for a state to be truly describable as a belief or as a desire; what, that is, needs to be the case according to our folk conception of belief and desire for a state to be a belief or a desire? And, second, is what needs to be the case in fact the case? Accordingly , if we accepted a certain, simple behaviourist account of, say, our folk Philosophical Studies 59:31--54, 1990. -

Maintaining Meaningful Expressions of Romantic Love in a Material World

Reconciling Eros and Neuroscience: Maintaining Meaningful Expressions of Romantic Love in a Material World by ANDREW J. PELLITIERI* Boston University Abstract Many people currently working in the sciences of the mind believe terms such as “love” will soon be rendered philosophically obsolete. This belief results from a common assumption that such terms are irreconcilable with the naturalistic worldview that most modern scientists might require. Some philosophers reject the meaning of the terms, claiming that as science progresses words like ‘love’ and ‘happiness’ will be replaced completely by language that is more descriptive of the material phenomena taking place. This paper attempts to defend these meaningful concepts in philosophy of mind without appealing to concepts a materialist could not accept. Introduction hilosophy engages the meaning of the word “love” in a myriad of complex discourses ranging from ancient musings on happiness, Pto modern work in the philosophy of mind. The eliminative and reductive forms of materialism threaten to reduce the importance of our everyday language and devalue the meaning we attach to words like “love,” in the name of scientific progress. Faced with this threat, some philosophers, such as Owen Flanagan, have attempted to defend meaningful words and concepts important to the contemporary philosopher, while simultaneously promoting widespread acceptance of materialism. While I believe that the available work is useful, I think * [email protected]. Received 1/2011, revised December 2011. © the author. Arché Undergraduate Journal of Philosophy, Volume V, Issue 1: Winter 2012. pp. 60-82 RECONCILING EROS AND NEUROSCIENCE 61 more needs to be said about the functional role of words like “love” in the script of progressing neuroscience, and further the important implications this yields for our current mode of practical reasoning. -

Mind and Language Seminar: Theories of Content

Mind and Language Seminar: Theories of Content Ned Block and David Chalmers Meetings • Main meeting: Tuesdays 4-7pm over Zoom [4-6pm in weeks without a visitor] • Student meeting: Mondays 5-6pm hybrid • Starting Feb 22 [only weeks with a visitor] • Enrolled students and NYU philosophy graduate students only. • Feb 2: Background: Theories of Content • Feb 9: Background: Causal/Teleological Theories • Feb 16: Background: Interpretivism • Feb 23: Nick Shea • March 2: Robbie Williams • March 9: Frances Egan • March 16: Adam Pautz • March 23: Veronica Gómez Sánchez • March 30: Background: Phenomenal Intentionality • April 6: Imogen Dickie • April 13: Angela Mendelovici • April 20: Background: Conceptual-Role Semantics • April 27: Christopher Peacocke • May 4: David Chalmers Assessment • Draft paper due April 19 • Term paper due May 17 Attendance Policy • Monday meetings: Enrolled students and NYU philosophy graduate students only. • Tuesday meetings: NYU and NYC Consortium students and faculty only • Very limited exceptions • Email us to sign up on email list if you haven’t already. Introductions Short History of the 20th Century • 1900-1970: Reduce philosophical questions to issues about language and meaning. • 1970s: Theories of meaning (philosophy of language as first philosophy) • 1980s: Theories of mental content (philosophy of mind as first philosophy). • 1990s: Brick wall. Theories of Content • What is content? • What is a theory of content? Content • Content (in the broadest sense?) is intentionality or aboutness • Something has content when it is about something. Contents • Content = truth-conditions • Content = satisfaction-conditions • Content = propositions • Content = objects of intentional states • Content = … What Has Content? • What sort of thing has content? What Has Content? • What sort of thing has content? • language (esp. -

Basic Brain Anatomy

Chapter 2 Basic Brain Anatomy Where this icon appears, visit The Brain http://go.jblearning.com/ManascoCWS to view the corresponding video. The average weight of an adult human brain is about 3 pounds. That is about the weight of a single small To understand how a part of the brain is disordered by cantaloupe or six grapefruits. If a human brain was damage or disease, speech-language pathologists must placed on a tray, it would look like a pretty unim- first know a few facts about the anatomy of the brain pressive mass of gray lumpy tissue (Luria, 1973). In in general and how a normal and healthy brain func- fact, for most of history the brain was thought to be tions. Readers can use the anatomy presented here as an utterly useless piece of flesh housed in the skull. a reference, review, and jumping off point to under- The Egyptians believed that the heart was the seat standing the consequences of damage to the structures of human intelligence, and as such, the brain was discussed. This chapter begins with the big picture promptly removed during mummification. In his and works down into the specifics of brain anatomy. essay On Sleep and Sleeplessness, Aristotle argued that the brain is a complex cooling mechanism for our bodies that works primarily to help cool and The Central Nervous condense water vapors rising in our bodies (Aristo- tle, republished 2011). He also established a strong System argument in this same essay for why infants should not drink wine. The basis for this argument was that The nervous system is divided into two major sec- infants already have Central nervous tions: the central nervous system and the peripheral too much moisture system The brain and nervous system. -

The Puzzle of Conscious Experience (Chalmers)

The Puzzle of Conscious Experience David J. Chalmers * From David Chalmers, "The Puzzle of Conscious Experience," Scientific American, 273 (1995), pp. 80-6. Reprinted by permission of the author. Conscious experience is at once the most familiar thing in the world and the most mysterious. There is nothing we know about more directly than consciousness, but it is extraordinarily hard to reconcile it with everything else we know. Why does it exist? What does it do? How could it possibly arise from neural processes in the brain? These questions are among the most intriguing in all of science. From an objective viewpoint, the brain is relatively comprehensible. When you look at this page, there is a whir of processing: photons strike your retina, electrical signals are passed up your optic nerve and between different areas of your brain, and eventually you might respond with a smile, a perplexed frown or a remark. But there is also a subjective aspect. When you look at the page, you are conscious of it, directly experiencing the images and words as part of your private, mental life. You have vivid impressions of colored flowers and vibrant sky. At the same time, you may be feeling some emotions and forming some thoughts. Together such experiences make up consciousness: the subjective, inner life of the mind. For many years consciousness was shunned by researchers studying the brain and the mind. The prevailing view was that science, which depends on objectivity, could not accommodate something as subjective as consciousness. The behaviorist movement in psychology, dominant earlier in this century, concentrated on external behavior and disallowed any talk of internal mental processes. -

Modal Empiricism and Two-Dimensional Semantics

=" Modal Empiricismand Two-DimensionalSemantics GergelyAmbrus, Miskolc, Hungary h45í2amb@he|ka.iif.hu l. The concept ofstrong necessity hold that zombies are not possible,even thoughtthey are li:, conceivab|e;víz. certain physica| (brain) events strong|y ]l"1 A strongly necessitates B, when it is not possible that A necessitateconscious events. This view is a version of a and not B, though it is conceivable that A and not B. In posteriorimaterialism, which holds that physical facts de- ..t anotherÍormu|ation: A entai|sB' but it is not priori a fuhatA terminefacts about consciousness.but thev do not deter- entails B (A does not imply B). Strong metaphysicatne- mine them a priori. cessities determine the space oÍ possib|e wor|ds. |f the T'1 space of possible worlds is sparser then the worlds which are (ideallyprimarily positively) conceivable, then whether ll. Chalmers' arguments against strong necessities a world is possible or not, is determinedby some meta- & physical fact, over and above the world's being (ideally One argument of David Chalmers against strong meta- primarily positively) conceivable.' Thus: accepting that physical necessities is the following.There are no candi- - - there are strong necessities commits one to modal empir- dates of strong necessities,except the alleged strong :l icsm;denying it, to modalrationalism. necessity of the brain-consciousnessrelation; and this 1: suggests that strong necessity is an ad froc inventionto a The concept oÍstrong necessity may be i||uminated save materialism.I shall argue, however, that it follows {. further by consideringthe relation between complete de- trom Chalmers, views on the semantics and ontology oÍ iui scriptionof a world w and a particulartrue statementS. -

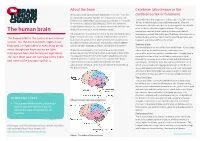

The Human Brain Hemisphere Controls the Left Side of the Body and the Left What Makes the Human Brain Unique Is Its Size

About the brain Cerebrum (also known as the The brain is made up of around 100 billion nerve cells - each one cerebral cortex or forebrain) is connected to another 10,000. This means that, in total, we The cerebrum is the largest part of the brain. It is split in to two have around 1,000 trillion connections in our brains. (This would ‘halves’ of roughly equal size called hemispheres. The two be written as 1,000,000,000,000,000). These are ultimately hemispheres, the left and right, are joined together by a bundle responsible for who we are. Our brains control the decisions we of nerve fibres called the corpus callosum. The right make, the way we learn, move, and how we feel. The human brain hemisphere controls the left side of the body and the left What makes the human brain unique is its size. Our brains have a hemisphere controls the right side of the body. The cerebrum is larger cerebral cortex, or cerebrum, relative to the rest of the The human brain is the centre of our nervous further divided in to four lobes: frontal, parietal, occipital, and brain than any other animal. (See the Cerebrum section of this temporal, which have different functions. system. It is the most complex organ in our fact sheet for further information.) This enables us to have abilities The frontal lobe body and is responsible for everything we do - such as complex language, problem-solving and self-control. The frontal lobe is located at the front of the brain. -

Tools of Pragmatism

Coping with the World: Tools of Pragmatism Mind, Brain and the Intentional Vocabulary Anders Kristian Krabberød Hovedoppgave Filosofisk Institutt UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Høsten 2004 Contents 1. Introduction.................................................................................................. 2 2. Different Ways of Describing the Same Thing ........................................... 7 3. Rorty and Vocabularies ............................................................................. 11 The Vocabulary-Vocabulary ...............................................................................................13 Reduction and Ontology......................................................................................................17 4. The Intentional Vocabulary and Folk Psychology: the Churchlands and Eliminative Materialism ................................................................................ 21 Eliminative Materialism......................................................................................................22 Dire Consequences..............................................................................................................24 Objecting against Eliminative Materialism..........................................................................25 1. The first objection: Eliminative materialism is a non-starter........................................27 2. The second objection: What could possibly falsify Folk Psychology?...........................29 3. The third objection: Folk Psychology is used