Folklife Center News, Volume XIV Number 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MIKE SEEGER I ELIZABETH COTTEN M~E.Lf to Rf.5Ef Today's Schedule - ALL FREE DI61TAL W,\TCHE5

Daily Zippy on Finals, see page 10 II FAIR TODAY with chance of precipitation near zero. High, up- 'Ver reen per 50s; Low, upper 30s. Tuesday, April 14, 1981 Pullman. Washington Vol. LXXXVII No.118 Establishecl1894 Surcharge will raise 500G ~\' KRISTIN RICHARDSON of meetings discussing' 'amounts, rarnifi- ~green Staff cations and 'should we or shouldn't we " resulted in the decision. said George "Jay" Hartford, vice president of busi- ti A 2.3 percent surcharge for administra·' ness and finance. ""V?se~vices of eight university operations Hartford. then budget director Pete " I I bring the administration $500,000 this Jear. ' Wollstein and then provost John Slaughter made the decision. I I~Plemented July 1, the charge is not The exemption of athletics, ASWSU and aeVledon athletics, ASWSU or the veterin- ry Clinic. the vet clinic resulted from budget prob- lems in those departments. Hamel said. , ,~he decision was made because of the , 'All are close financially, having a hard s ttght fiscal situation" of the university, time facing their budgets and staying r:ld Joe Hamel, assistant vice president of nance, within them," he said. "Raising. fees, d The percentage comes off what the would only be negative while they are thPartments collect in gross receipts. For trying to payoff deficits." rose departments' 'performing a service In addition. Hartford said taking money from athletics increases the amount of c~r Operating areas of the university", state support necessary to help make up c arges pay part of "indirect costs and its deficit. "We would end up giving them entral service" provided by WSU. -

Bob Dylan - Unreleased Performances 2

1. Friend Of The Devil (6:20) Frankenstadion, Nürnberg, Germany 5/31/98 A performance of the Hunter-Garcia classic, "Friend of the Devil." Bob Dylan - Unreleased Performances 2. Oh Babe, It Ain't No Lie (5:04) Stadtpark, Hamburg, Germany 6/12/98 Another Elizabeth Cotten song. Find out more on the Cowboy Angel Sings website. Itsuko Nishimura has created a web site called In Search of Elizabeth Cotten. 3. Shake Sugaree (5:12) The Roxy, Atlanta, Georgia 12/1/97 The Elizabeth Cotten (1895-1987) song, sometimes known as "I've Got A Secret." Find out more on the Cowboy Angel Sings website. There's also an interesting exigesis of "Shake Sugaree" in an essay by Gary Knigge. Itsuko Nishimura has created a web site called In Search of Elizabeth Cotten. Bob Dylan has also performed the Cotten composition "Oh, Babe, It Ain't No Lie." 4. I and I , Forum, Dijon, France 7/1/98 (6:22) "I and I" was officially released on Infidels and on the 1984 live album Real Live. This performance comes from Bob Dylan's recent European tour. 5. Senor, Piazza Napoleone, Lucca, Italy 7/6/98 (4:27) "Senor" was officially released on Street Legal. This performance comes from a public square in Italy on Bob Dylan's recent European tour. "Senor" was covered regularly by the Jerry Garcia Band. 6. Mama, You Been On My Mind, Brussels, Belgium 6/17/98 (4:35) "Mama, You Been On My Mind" has been part of Bob Dylan's performing repertoire for over thirty years. -

Celebrating African American History February 2019 – Week 2

Celebrating African American History February 2019 – Week 2 28 biographies for 28 days compiled by Reverend Carolyn Matthews Rose Marie McCoy (1922 – 2015) In the spirit of Sister Rosetta Tharpe, here is another name that is important in music history. In McCoy’s biography, in the chapter titled, “Where’s the Music From,” she says the following: “It’s a gift from God. It’s inspirational. I just write what happens. It’s like you talk and then it automatically rhymes itself.” Rose Marie McCoy was one of the most prolific and versatile songwriters in the history of American music. A true pioneer, she broke into the white male-dominated music business in the early 1950s, not only writing songs, but also producing records and forming her own publishing firm. “She knew how to hang in there with the big boys,” remembers singer Maxine Brown. “Everyone was scrapping to get there, but it was always men. Women didn’t have a place, so she made a place for herself.” Rose Marie McCoy was born April 19, 1922 in Oneida, Arkansas and lived in a tin-top shack on a 40-acre farm her parents were renting. Though she lived in the Mississippi Delta, often referred to as the birthplace of the blues, the blues was not heard in Oneida, for many there considered it “the devil’s music.” But plenty of blues was heard 18 miles away in Helena, Arkansas, and since Helena was where the closest high school for blacks was located, McCoy was sent there to live with her grandparents. -

Come Hear North Carolina Backgrounder

COME HEAR NORTH CAROLINA BACKGROUNDER Come Hear North Carolina is a promotional campaign of the North Carolina Department of Natural & Cultural Resources, and the North Carolina Arts Council designed to celebrate North Carolinians groundbreaking contributions to many of America’s most important musical genres — blues, bluegrass, jazz, gospel, funk, rock, and everything in-between. Our goal is to share and promote authentic and compelling stories about music and musicians in North Carolina — especially those that demonstrate our state’s influence on American music — with residents and visitors. why: 1. Many North Carolina musicians have made North Carolina music globally appreciated and celebrated, such as: • Jazz visionaries John Coltrane, Nina Simone, Thelonious Monk, Billy Taylor, and Max Roach; • Banjo and guitar innovators Earl Scruggs and Doc Watson; • Piedmont blues greats Elizabeth Cotten, Blind Boy Fuller, and Etta Baker; • Gospel titans Reverend Faircloth Barnes and Shirley Caesar; • Funk architects Maceo and Melvin Parker, Nat Jones and George Clinton; • Rock, pop and country artists Link Wray, Roberta Flack, James Taylor, and Don Gibson, among others; • J. Cole, 9th Wonder, and Rapsody in hip-hop; • Superchunk, the Avett Brothers, and Sylvan Esso in indie. 2. Nearly 25,000 North Carolinians work in music occupations including musicians and singers, music directors, composers and songwriters, instrument makers, producers, conductors, event and venue promoters, recording engineers and record label owners – enriching our cultural life in addition to adding significantly to North Carolina’s economic prosperity. 3. North Carolina created the first state-supported orchestra in the nation, the North Carolina Symphony, which performs 175 annual concerts and events throughout the state. -

Freight Train and Other North Carolina Folk Songs and Tunes

“’Freight Train,’ and Other North Carolina Folk Songs and Tunes”--Elizabeth Cotten (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2007 Essay by Maya Lerman Elizabeth Cotten Elizabeth Cotten’s uniquely American guitar style and songs have woven their way into the tapestry of American folk music. She was unknown in the music world until she was in her 60s, when her playing, singing, and songwriting came to play a major role in the revival of traditional folk music and even made its way into popular music. Born in 1893, Elizabeth Cotten grew up in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where her father worked in the ore mines and her mother performed domestic housework. One of four children, Cotten early on became fixated on learning and practicing music. She taught herself to play on her brother’s banjo when she was only eight, and not much later to play on his guitar, which he thought he had hidden from her. Before the age of 12, Cotten found a job doing housework for a family. With the minimal money she earned--no more than one dollar a month--she was able to purchase her first guitar, which she named “Stella.” As a young girl she played her guitar at every opportunity, developing her style as a left-handed player and playing with her siblings around their home. When practicing, she would lay the guitar flat on her lap and teach herself song melodies and rhythms. The distinctive way she learned involved practicing with one string and finger, gradually working her way to a three-finger picking pattern. -

Freight Train Free

FREE FREIGHT TRAIN PDF Donald Crews | 32 pages | 21 Jan 2003 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780688117016 | English | New York, NY, United States Guitar Tablature: "Freight Train" - dummies Freight Train your Spotify account to your Last. Connect to Spotify. A new version of Last. Replace video. Do you know any background info about this track? Start the wiki. Elizabeth Cotten. Freight Train you know the lyrics for this track? Add lyrics on Musixmatch. Don't want to see ads? Upgrade Now. Scrobbling is when Last. Learn more. Javascript is required to view shouts on this page. Freight Train directly to shout page. View full artist profile. View all similar artists. View all trending tracks. Loading player…. Scrobble from Spotify? Connect to Spotify Dismiss. Search Search. Play album. Length Related Tags folk blues country Add tags View all tags. From The Album Play album. Play track. Artist images 9 Freight Train. Elizabeth Cotten 78, listeners Related Tags blues folk female vocalists Elizabeth "Libba" Cotten January 5, — June 29, was an American blues and folk musician, singer, and songwriter. A self-taught left-handed guitarist, Cotten developed her own original style. Her approach involved using a right-handed guitar usually in standard tuningnot re-strung for left-handed playing, essentially, holding a right-handed guitar upside down. This position required her to play the bass lines with her fingers and the melody with her thumb. Her signature alternating bass style has become known as "Cotten picking". Elizabeth Nevills w… read more. Elizabeth "Libba" Cotten January 5, — June 29, was an American blues and folk musician, singer, and songwriter. -

Folklore Journal North Carolina

Folklore Journal North Carolina Carolina North 57.2 Fall-Winter 2010 Fall-Winter 57.2 North Carolina Folklore Journal Philip E. (Ted) Coyle, Editor Jared W. Gallamore, Assistant Editor The North Carolina Folklore Journal is published twice a year by the North Carolina Folklore Society with assistance from Western Carolina University, Appalachian State University, and a grant from the North Carolina Arts Council, an agency funded by the State of North Carolina and the National Endowment for the Arts. Editorial Advisory Board (2006-2010) Barbara Duncan, Museum of the Cherokee Indian Alan Jabbour, American Folklife Center (retired) Erica Abrams Locklear, University of North Carolina at Asheville Thomas McGowan, Appalachian State University Carmine Prioli, North Carolina State University Kim Turnage, Lenoir Community College The North Carolina Folklore Journal publishes studies of North Carolina folklore and folklife, analyses of folklore in Southern literature, and articles whose rigorous or innovative approach pertains to local folklife study. Manuscripts should conform to The MLA Style Manual. Quotations from oral narratives should be transcriptions of spoken texts and should be identified by informant, place, and date. For informa- tion regarding submissions, view our website (http:/paws.wcu.edu/ncfj), or contact: Dr. Philip E. Coyle Department of Anthropology and Sociology Western Carolina University Cullowhee, NC 28723 North Carolina Folklore Society 2010 Officers Barbara Lau, Durham, President Lora Smith, Pittsboro, 1st Vice President Shelia Wilson, Burlington, 2nd Vice President Steve Kruger, Hillsborough, 3rd Vice President Joy M. Salyers, Hillsborough, Secretary Janet Hoshour, Hillsborough, Treasurer North Carolina Folklore Society memberships are $20 per year for individuals; student memberships are $15. -

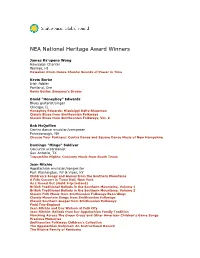

James Ka`Upena Wong

NEA National Heritage Award Winners James Ka’upena Wong Hawaaian Chanter Wainae, HI Hawaiian Drum Dance Chants: Sounds of Power in Time Kevin Burke Irish fiddler Portland, Ore Kevin Burke: Sweeney's Dream David "Honeyboy" Edwards Blues guitarist/singer Chicago, IL Honeyboy Edwards: Missisippi Delta Bluesman Classic Blues from Smithsonian Folkways Classic Blues from Smithsonian Folkways, Vol. 2 Bob McQuillen Contra dance musician/composer Peterborough, NH Choose Your Partners: Contra Dance and Square Dance Music of New Hampshire Domingo "Mingo" Saldivar Conjunto accordionist San Antonio, TX Taquachito Nights: Conjunto Music from South Texas Jean Ritchie Appalachian musician/songwriter Port Washington, NY & Viper, KY Children's Songs and Games from the Southern Mountains A Folk Concert in Town Hall, New York As I Roved Out (Field Trip-Ireland) British Traditional Ballads in the Southern Mountains, Volume 1 British Traditional Ballads in the Southern Mountains, Volume 2 Classic Folk Music from Smithsonian Folkways Recordings Classic Mountain Songs from Smithsonian Folkways Classic Southern Gospel from Smithsonian Folkways Field Trip-England Jean Ritchie and Doc Watson at Folk City Jean Ritchie: Ballads from her Appalachian Family Tradition Marching Across The Green Grass and Other American Children's Game Songs Precious Memories Smithsonian Folkways Children's Collection The Appalachian Dulcimer: An Instructional Record The Ritchie Family of Kentucky Wilson "Boozoo" Chavis Creole Zdeco Accordionist Lake Charles, LA Blues Routes: Heroes and Tricksters: Blues and Jazz Work Songs and Street Music Hazel Dickens Appalachian Singer-Songwriter Washington, DC and Montcalm, WV American Banjo: Three-Finger and Scruggs Style Classic Bluegrass from Smithsonian Folkways Classic Bluegrass Vol. -

Dylan Before

the unseen photos of Joe Alper 1961-1965 dylan before dylan Wall of sound gallery dylan before 16.05 | 21.07.13 dylan for the first time, A europeAn exclusive, the unseen photos of Joe Alper 1961-1965 Wall Of SOund Gallery This exhibition is included Cristina Pelissero in the City of Alba’s event “Primavera di Bellezza” Via Gastaldi, 4 12051 Alba (CN), Italy +39-0173-362324 [email protected] ©2013 Wall Of Sound Gallery / HRR Edizioni www.wallofsoundgallery.com The Joe Alper Photo Collection LLC Graphic design: Hours: Tuesday / Saturday GUIDO HARARI e ANNA FOSSATO 10.30-12.30 / 15.30-19.30 Sunday 15.30-19.30 Acknowledgments: EDWARD ELBERS and the JOE ALPER PHOTO Closed monday COLLECTION LLC, GEORGE ALPER, LEN CHARNEY, ERIC PERSON for starting the ball, DONALD PERSON Press office: for saving the show from shipwrecking. clarart Claudia Ratti +39-039-2721502 This catalogue cannot be reproduced in whole or in part [email protected] in any form without the written authorization of the www.clarart.com copyright owners and publisher. 1. Celebrating the 50th anniversary of Blowin’ in the Wind Wall Of Sound Gallery is proud to present, for ditions. At the time the Village is also one of a the first time ever and as a European exclusive, few interracial melting pots. the “DYLAN BEFORE DYLAN” exhibition with the Being a huge fan of Woody Guthrie, the great historic photographs by Joe Alper. folk legend who’s dying at the Brooklyn State Like last year with the Art Kane show, the edit- Hospital, Dylan sports a business card that says ing, the restoration of the original negatives as “I ain’t dead yet”, signed WG. -

The Cultural Politics of the North American Folk Music Revival in Washington, D.C

Cosmopolitan Folk: The Cultural Politics of the North American Folk Music Revival in Washington, D.C. by Stephen Fox Lorenz B.A. in English, May 1990, Washington College M.A. in American Studies, May 2003, The George Washington University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 18th, 2014 Dissertation directed by Joseph Kip Kosek Associate Professor of American Studies and John Vlach Professor Emeritus of American Studies and of Anthropology The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Stephen Fox Lorenz has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of March 20th, 2014. This is the final approved form of the dissertation. Cosmopolitan Folk: The Cultural Politics of the North American Folk Music Revival in Washington, D.C. Stephen Fox Lorenz Dissertation Research Committee: Joseph Kip Kosek, Associate Professor of American Studies, Dissertation Co-Director John Vlach, Professor Emeritus of American Studies and of Anthropology, Dissertation Co-Director Michael Taft, Head of the Archive of Folk Culture at The American Folklife Center (Retired), Committee Member Suleiman Osman, Associate Professor of American Studies, Department Reader ii © Copyright 2014 by Stephen Fox Lorenz All rights reserved iii Dedication The author wishes to dedicate this work to his father Jack Lorenz. Who knew all those trips as a kid to hear bluegrass at the Birchmere would lead here? iv Acknowledgements The author wishes to acknowledge and thank the individuals who gave interviews, special advice, and support for this dissertation. -

World of Sound Catalog Wholesale List

WORLD OF SOUND CATALOG WHOLESALE LIST ORGANIZED IN ORDER BASED ON RECORD LABEL Smithsonian Folkways Recordings ◊ Collector Records ◊ Consignment ◊ Cook Records ◊ Dyer-Bennet Records ◊ Fast Folk Musical Magazine ◊ Folkways Records ◊ Monitor Records ◊ Minority Owned Record Enterprises (M.O.R.E.) ◊ Paredon Records ◊ Smithsonian Folkways Special Series Published 3/3/2011 Smithsonian Folkways Recordings CATALOG NO. ALBUM TITLE ALBUM ARTIST YEAR SFW40000 Folkways: The Original Vision Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly 2005 SFW40002 Musics of the Soviet Union Various Artists 1989 SFW40003 Happy Woman Blues Lucinda Williams 1990 SFW40004 Country Songs, Old and New The Country Gentlemen 1990 SFW40005 Jean Ritchie and Doc Watson at Folk City Jean Ritchie and Doc Watson 1990 SFW40006 Cajun Social Music Various Artists 1990 SFW40007 Woody Guthrie Sings Folk Songs Woody Guthrie 1989 SFW40008 Broadside Tapes 1 Phil Ochs 1989 SFW40009 Freight Train and Other North Carolina Folk Songs and Tunes Elizabeth Cotten 1989 SFW40010 Lead Belly Sings Folk Songs Lead Belly 1989 SFW40011 Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry Sing Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee 1990 SFW40012 The Doc Watson Family The Doc Watson Family 1990 SFW40013 Family Songs and Stories from the North Carolina Mountains Doug and Jack Wallin 1995 SFW40014 Puerto Rican Music in Hawaii Various Artists 1989 SFW40015 Hawaiian Drum Dance Chants: Sounds of Power in Time Various Artists 1989 Musics of Hawai'i: Anthology of Hawaiian Music - Special Festival SFW40016 Various Artists 1989 Edition SFW40017 Tuva: Voices from the Center of Asia Various Artists 1990 SFW40018 Darling Corey/Goofing-Off Suite Pete Seeger 1993 SFW40019 Lightnin' Hopkins Lightnin' Hopkins 1990 SFW40020 Mountain Music of Peru, Vol. -

This Year We Furthered Our Research to Name 100

100 Historic Black Women Guitarists and Bassists You Need To Know 02.13.20 Written by She Shreds Staff 35 This year we furthered our research to name 100 black women guitarists because we believe in constantly celebrating Black and Afro-identifying communities around the world—a statement meant to prove the disparity between the history we’re told and the history that exists. Last February, we published “50 Historic Black Women Guitarists and Bassists You Needs to Know” to showcase the influences that black, indigenous, and Afro-identifying women musicians have had on music history. For 2020, we updated the list to 100 black women guitarists, because we should constantly be celebrating the innovation, resilience, and talent of black music communities. For this particular list, we choose to focus on black women guitarists and bassists from prior to 1999. We did this specifically to showcase the legends—many of whom unfortunately have been overlooked, dismissed, or forgotten—that should be recognized as pillars of music history. This list is not to be brushed off as just another list. Rather, it should be treated as a step taken towards exposing the truth. It’s for all of us who aren’t able to count the names of black women guitarists on one hand. It’s for the young black girls aspiring to be musicians but seldom see a history that represents them. It’s to learn about our past and evolve into our future— and without black history, we cannot accurately do so. Below are 100 women, some of which you’ve heard about countless times, such as Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Elizabeth Cotten, and Barbara Lynn.