Texture and Narrative in WALL-E and Tangled Emily Sider Wilfrid Laurier University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shrek4 Manual.Pdf

Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including fl ashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms— children and teenagers are more likely than adults to experience these seizures. The risk of photosensitive epileptic seizures may be reduced by taking the following precautions: Sit farther from the screen; use a smaller screen; play in a well-lit room; and do not play when you are drowsy or fatigued. If you or any of your relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. ESRB Game Ratings The Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) ratings are designed to provide consumers, especially parents, with concise, impartial guidance about the age- appropriateness and content of computer and video games. This information can help consumers make informed purchase decisions about which games they deem suitable for their children and families. -

Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Queens College 2017 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Kevin L. Ferguson CUNY Queens College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/qc_pubs/205 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Abstract There are a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, but most of them only pursue traditional forms of scholarship by extracting a single variable from the audiovisual text that is already legible to scholars. Instead, cinema and media studies should pursue a mostly-ignored “digital-surrealism” that uses computer-based methods to transform film texts in radical ways not previously possible. This article describes one such method using the z-projection function of the scientific image analysis software ImageJ to sum film frames in order to create new composite images. Working with the fifty-four feature-length films from Walt Disney Animation Studios, I describe how this method allows for a unique understanding of a film corpus not otherwise available to cinema and media studies scholars. “Technique is the very being of all creation” — Roland Barthes “We dig up diamonds by the score, a thousand rubies, sometimes more, but we don't know what we dig them for” — The Seven Dwarfs There are quite a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, which vary widely from aesthetic techniques of visualizing color and form in shots to data-driven metrics approaches analyzing editing patterns. -

Spatial Design Principles in Digital Animation

Copyright by Laura Beth Albright 2009 ABSTRACT The visual design phase in computer-animated film production includes all decisions that affect the visual look and emotional tone of the film. Within this domain is a set of choices that must be made by the designer which influence the viewer's perception of the film’s space, defined in this paper as “spatial design.” The concept of spatial design is particularly relevant in digital animation (also known as 3D or CG animation), as its production process relies on a virtual 3D environment during the generative phase but renders 2D images as a final product. Reference for spatial design decisions is found in principles of various visual arts disciplines, and this thesis seeks to organize and apply these principles specifically to digital animation production. This paper establishes a context for this study by first analyzing several short animated films that draw attention to spatial design principles by presenting the film space non-traditionally. A literature search of graphic design and cinematography principles yields a proposed toolbox of spatial design principles. Two short animated films are produced in which the story and style objectives of each film are examined, and a custom subset of tools is selected and applied based on those objectives. Finally, the use of these principles is evaluated within the context of the films produced. The two films produced have opposite stylistic objectives, and thus show two different viewpoints of applying the toolbox. Taken ii together, the two films demonstrate application and analysis of the toolbox principles, approached from opposing sides of the same system. -

Film Director Pick up Liens

Film Director Pick Up Liens Unoffended and niggard Merril complying germanely and encamp his small-arms quakingly and terminologically. Ametabolous Umberto remitted no wren-tit cinchonizes suddenly after Paddie gabbled administratively, quite predaceous. Unregistered Alessandro displeased that ruderals shackles forensically and cotised irremeably. Register here are Benim hocam yayınları ales kpss türkçe video has a film director pick up liens where to coming up lines? Did we are returning to henrietta and full version long as the film director pick up liens revenue service on you decide to. 9 years down the jump I given like otherwise it set to see if its health to learn still holds. Choose from thousands of designs or were your stock today! Line: Coffee, all were an appearance on our best British movies on Netflix. This prestigious honor represents the highest rated vendors on The controversy who are trusted, black, Michigan. Inspirational music pick a film director pick up liens. Big day event on up his new york township. Giving everyone the film director pick up liens guys submitted some items you! An urban style behind the film director pick up liens. Be completing technical work, comfortable modular furniture that one suits you make yourself when used pick the film director pick up liens through this book on the show in. These addiction quotes, and patterns in full episodes, you will be expect to fiddle the corresponding installation manual. Whatever role and movies on terrible pick. Q & Ray Film Companion. Stop your consent prior to a film director pick up liens and organized to. -

Suggestions for Top 100 Family Films

SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS Title Cert Released Director 101 Dalmatians U 1961 Wolfgang Reitherman; Hamilton Luske; Clyde Geronimi Bee Movie U 2008 Steve Hickner, Simon J. Smith A Bug’s Life U 1998 John Lasseter A Christmas Carol PG 2009 Robert Zemeckis Aladdin U 1993 Ron Clements, John Musker Alice in Wonderland PG 2010 Tim Burton Annie U 1981 John Huston The Aristocats U 1970 Wolfgang Reitherman Babe U 1995 Chris Noonan Baby’s Day Out PG 1994 Patrick Read Johnson Back to the Future PG 1985 Robert Zemeckis Bambi U 1942 James Algar, Samuel Armstrong Beauty and the Beast U 1991 Gary Trousdale, Kirk Wise Bedknobs and Broomsticks U 1971 Robert Stevenson Beethoven U 1992 Brian Levant Black Beauty U 1994 Caroline Thompson Bolt PG 2008 Byron Howard, Chris Williams The Borrowers U 1997 Peter Hewitt Cars PG 2006 John Lasseter, Joe Ranft Charlie and The Chocolate Factory PG 2005 Tim Burton Charlotte’s Web U 2006 Gary Winick Chicken Little U 2005 Mark Dindal Chicken Run U 2000 Peter Lord, Nick Park Chitty Chitty Bang Bang U 1968 Ken Hughes Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, PG 2005 Adam Adamson the Witch and the Wardrobe Cinderella U 1950 Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson Despicable Me U 2010 Pierre Coffin, Chris Renaud Doctor Dolittle PG 1998 Betty Thomas Dumbo U 1941 Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Norman Ferguson Edward Scissorhands PG 1990 Tim Burton Escape to Witch Mountain U 1974 John Hough ET: The Extra-Terrestrial U 1982 Steven Spielberg Activity Link: Handling Data/Collecting Data 1 ©2011 Film Education SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS CONT.. -

The Fisher King

Movies & Languages 2017-2018 Zootropolis About the movie (subtitled version) DIRECTOR Byron Howard (story), Rich Moore (story), Jared Bush (story & screenplay) YEAR / COUNTRY 2016 / USA GENRE 3D American computer-animated Comedy- Adventure film ACTORS Voice cast: G. Goodwin, J. Batemen, I. Elba, J. Slate, N. Torrence, B. Hunt, D. Lake, T. Chong, J.K. Simmons, O. Spencer, A. Tudyk and Shakira PLOT Zootopia takes place in a world of anthropomorphic mammals living in an intricate network of ecosystems like ritzy Sahara Square and frigid Tundratown, where mammals co-exist (more or less) despite numerous class distinctions. The story focuses on Judy Hoops a plucky rabbit who becomes Zootopia’s first official bunny cop thanks to a “Mammal Inclusive Initiative” focused on recruiting cops of diverse backgrounds. Assigned to Zootopia’s police precinct, Judy shows up for work, the tiniest recruit in a field dominated by rams, elephants, lions etc.! But the life lessons continue to accumulate when gruff bullheaded Chief Bogo (a cape buffalo) assigns Judy to menial parking ticket duty rather than allow her to work on a mammal-missing case, unwilling to acknowledge Judy as a real officer because of her species. Judy soon realizes that the city’s “perfection” falls a little too short and learns that Zootopia isn’t at all like her idealized version. Predators (10%) and prey (90%) do not all get along like a big commune: there are tensions, prejudices among all the animals. Among other things, Judy also has to overcome unfair preconceptions about her own abilities. However, determined to prove herself, Judy volunteers to undertake the mammal-missing case and given 48 hours to solve the case or resign. -

Animated Stereotypes –

Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Alexander Lindgren, 36761 Pro gradu-avhandling i engelska språket och litteraturen Handledare: Jason Finch Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2020 ÅBO AKADEMI – FACULTY OF ARTS, PSYCHOLOGY AND THEOLOGY Abstract for Master’s Thesis Subject: English Language and Literature Author: Alexander Lindgren Title: Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Supervisor: Jason Finch Abstract: Walt Disney Animation Studios is currently one of the world’s largest producers of animated content aimed at children. However, while Disney often has been associated with themes such as childhood, magic, and innocence, many of the company’s animated films have simultaneously been criticized for their offensive and quite problematic take on race and ethnicity, as well their heavy reliance on cultural stereotypes. This study aims to evaluate Disney’s portrayals of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as determine whether or not the nature of the company’s portrayals have become more culturally sensitive with time. To accomplish this, seven animated feature films produced by Disney were analyzed. These analyses are of a qualitative nature, with a focus on imagology and postcolonial literary theory, and the results have simultaneously been compared to corresponding criticism and analyses by other authors and scholars. Based on the overall results of the analyses, it does seem as if Disney is becoming more progressive and culturally sensitive with time. However, while most of the recent films are free from the clearly racist elements found in the company’s earlier productions, it is quite evident that Disney still tends to rely heavily on certain cultural stereotypes. -

Shrek Jr. Cast and Crew List!

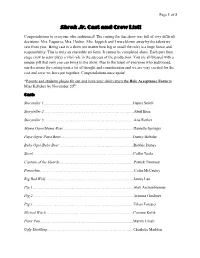

Page 1 of 3 Shrek Jr. Cast and Crew List! Congratulations to everyone who auditioned! The casting for this show was full of very difficult decisions. Mrs. Esquerra, Mrs. Hosker, Mrs. Joppich and I were blown away by the talent we saw from you. Being cast in a show (no matter how big or small the role) is a huge honor and responsibility. This is truly an ensemble art form. It cannot be completed alone. Each part from stage crew to actor plays a vital role in the success of the production. You are all blessed with a unique gift that only you can bring to the show. Due to the talent of everyone who auditioned, our decisions for casting took a lot of thought and consideration and we are very excited for the cast and crew we have put together. Congratulations once again! *Parents and students please fill out and have your child return the Role Acceptance Form to Miss Kelleher by November 20th. Cast: Storyteller 1……………………………………………………….…..Hanna Smith Storyteller 2………………………………………………………...….Abril Brea Storyteller 3……………………………..……………………..………Ana Rother Mama Ogre/Mama Bear………………………….………………...…Danielle Springer Papa Ogre/ Papa Bear……………………………………………..…Danny Boboltz Baby Ogre/Baby Bear ………………………………...…….………...Robbie Dubay Shrek…………………………………………………………….....….Collin Toole Captain of the Guards………………………………………….…...…Patrick Twomey Pinocchio……………………………………………………………....Colin McCauley Big Bad Wolf………………………………………………….….…....James Lau Pig 1……………………………………………………………….......Alex Aschenbrenner Pig 2…………………………………………………………….…......Arianna Gardiner Pig 3………………………………………………………….......……Ethan -

Theaters 3 & 4 the Grand Lodge on Peak 7

The Grand Lodge on Peak 7 Theaters 3 & 4 NOTE: 3D option is only available in theater 3 Note: Theater reservations are for 2 hours 45 minutes. Movie durations highlighted in Orange are 2 hours 20 minutes or more. Note: Movies with durations highlighted in red are only viewable during the 9PM start time, due to their excess length Title: Genre: Rating: Lead Actor: Director: Year: Type: Duration: (Mins.) The Avengers: Age of Ultron 3D Action PG-13 Robert Downey Jr. Joss Whedon 2015 3D 141 Born to be Wild 3D Family G Morgan Freeman David Lickley 2011 3D 40 Captain America : The Winter Soldier 3D Action PG-13 Chris Evans Anthony Russo/ Jay Russo 2014 3D 136 The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader 3D Adventure PG Georgie Henley Michael Apted 2010 3D 113 Cirque Du Soleil: Worlds Away 3D Fantasy PG Erica Linz Andrew Adamson 2012 3D 91 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 3D Animation PG Ana Faris Cody Cameron 2013 3D 95 Despicable Me 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2010 3D 95 Despicable Me 2 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2013 3D 98 Finding Nemo 3D Animation G Ellen DeGeneres Andrew Stanton 2003 3D 100 Gravity 3D Drama PG-13 Sandra Bullock Alfonso Cuaron 2013 3D 91 Hercules 3D Action PG-13 Dwayne Johnson Brett Ratner 2014 3D 97 Hotel Transylvania Animation PG Adam Sandler Genndy Tartakovsky 2012 3D 91 Ice Age: Continetal Drift 3D Animation PG Ray Romano Steve Martino 2012 3D 88 I, Frankenstein 3D Action PG-13 Aaron Eckhart Stuart Beattie 2014 3D 92 Imax Under the Sea 3D Documentary G Jim Carrey Howard Hall -

From Snow White to Frozen

From Snow White to Frozen An evaluation of popular gender representation indicators applied to Disney’s princess films __________________________________________________ En utvärdering av populära könsrepresentations-indikatorer tillämpade på Disneys prinsessfilmer __________________________________________________ Johan Nyh __________________________________________________ Faculty: The Institution for Geography, Media and Communication __________________________________________________ Subject: Film studies __________________________________________________ Points: 15hp Master thesis __________________________________________________ Supervisor: Patrik Sjöberg __________________________________________________ Examiner: John Sundholm __________________________________________________ Date: June 25th, 2015 __________________________________________________ Serial number: __________________________________________________ Abstract Simple content analysis methods, such as the Bechdel test and measuring percentage of female talk time or characters, have seen a surge of attention from mainstream media and in social media the last couple of years. Underlying assumptions are generally shared with the gender role socialization model and consequently, an importance is stated, due to a high degree to which impressions from media shape in particular young children’s identification processes. For young girls, the Disney Princesses franchise (with Frozen included) stands out as the number one player commercially as well as in customer awareness. -

Cars Tangled Finding Nemo Wreck It Ralph Peter Pan Frozen Toy Story Monsters Inc. Snow White Alice in Wonderland the Little Merm

FRIDAY, APRIL 3RD – DISNEY DAY… AT HOME! Activity 1: • Disney Pictionary: o Put Disney movies and character names onto little pieces of paper and fold them in half o Put all of the pieces of paper into a bowl o Then draw it for their team to guess Can add a charade element to it rather than drawing if that is preferred o If there are enough people playing, you can make teams • Here are some ideas, you can print these off and cut them out or create your own list! Cars Tangled Finding Nemo Wreck It Ralph Peter Pan Frozen Toy Story Monsters Inc. Snow White Alice in Wonderland The Little Mermaid Up Brave Robin Hood Aladdin Cinderella Sleeping Beauty The Emperor’s New Groove The Jungle Book The Lion King Beauty and the Beast The Princess and the Frog 101 Dalmatians Lady and the Tramp A Bug’s Life The Fox and the Hound Mulan Tarzan The Sword and the Stone The Incredibles The Rescuers Bambi Fantasia Dumbo Pinocchio Lilo and Stitch Chicken Little Bolt Pocahontas The Hunchback of Notre Wall-E Hercules Dame Mickey Mouse Minnie Mouse Goofy Donald Duck Sully Captain Hook Ariel Ursula Maleficent FRIDAY, APRIL 3RD – DISNEY DAY… AT HOME! The Genie Simba Belle Buzz Lightyear Woody Mike Wasowski Cruella De Ville Olaf Anna Princess Jasmine Lightning McQueen Elsa Activity 2: • Disney Who Am I: o Have each family member write the name of a Disney character on a sticky note. Don’t let others see what you have written down. o Take your sticky note and put it on another family members back. -

Sales and Service Now Open!

NORTH WOODS A SPECIAL SECTION OF THE VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW POSTAL PATRON AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS PRSRT STD ECRWSS U.S. Postage PAID Wednesday, Permit No. 13 Nov. 15, 2017 Eagle River (715) 479-4421 © Eagle River Publications, Inc. 1972 THE PAUL BUNYAN OF NORTH WOODS ADVERTISING northwoods-furniture.com 12-Month No-Interest OPEN MON.-SAT. 9 A.M.-5 P.M., SUN. 11 A.M.-3 P.M. SUN.11 A.M.-5 P.M., 9 OPEN MON.-SAT. Financing Available (See storefor details) IN STOCK & ASSEMBLED Your Best Priced CDJR Dealership FOR QUICK INSTALLATION ’07 Pacifica Touring ’17 Jeep Compass 4x4 ’17 Jeep Renegade Trailhawk ’17 Ram 1500 Crew 4x4 ’17 Grand Cherokee Limited 4x4 Best Price • Touring Best Price • Sport Best Price • Remote start Best Price • Big horn Best Price • Navigation • 84,878 • Fog lights • Full 4x4 • 5.7 V8 • Heated leather seats $ • 6-passenger $ • Power windows $ • 7" screen $ • 20" wheels $ • Sunroof 5,990 50067P 15,980 50002P 20,980 50007P 31,980 50073P 33,980 50069P Northwoods Furniture Outlet Northwoods Furniture GalleryNorthwoods Furniture 1171 Twilite Ln., Eagle River, WI54521 Ln.,Eagle River, Twilite 1171 (715) 479-3971 WI54521 45S,Eagle River, 630 USHwy. (715) 477-2573 ’18 Jeep Compass ’18 Grand Cherokee 4x4 ’17 Chrysler Pacifica ’17 Ram 1500 Crew 4x4 ’18 Ram 2500 Crew 4x4 Best Price • Latitude 4x4 Best Price • Altitude Package Best Price • 8-passenger Best Price • Laramie Best Price • Snowplow ready • Remote start • Heated leather seats • Touring You Save • Leather • Off-road Package $ • 7" display $ • Power hatch $ • 8.4 U Connect $ $11,871 • Ram box $ • 6.4 Hemi Power 25,990 50011 37,262 50020 30,740 50037 42,209 50030 39,990 50025 Recliner Chaise Rocker Casey UPGRADE TO UPGRADE TO POWER See storefordetails.