New Consensus, New Keynesianism, and the Economics of the 'Third

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monetary Policy in Economies with Little Or No Money

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES MONETARY POLICY IN ECONOMIES WITH LITTLE OR NO MONEY Bennett T. McCallum Working Paper 9838 http://www.nber.org/papers/w9838 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 July 2003 This paper was prepared for presentation at the December 16-17, 2002, meeting of the Hong Kong Economic Association. I am indebted to Marvin Goodfriend, Lok Sang Ho, Allan Meltzer, and Edward Nelson for helpful comments and suggestions. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Bureau of Economic Research ©2003 by Bennett T. McCallum. All rights reserved. Short sections of text not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit including © notice, is given to the source. Monetary Policy in Economies with Little or No Money Bennett T. McCallum NBER Working Paper No. 9838 July 2003 JEL No. E3, E4, E5 ABSTRACT The paper's arguments include: (1) Medium-of-exchange money will not disappear in the foreseeable future, although the quantity of base money may continue to decline. (2) In economies with very little money (e.g., no currency but bank settlement balances at the central bank), monetary policy will be conducted much as at present by activist adjustment of overnight interest rates. Operating procedures will be different, however, with payment of interest on reserves likely to become the norm. (3) In economies without any money there can be no monetary policy. The relevant notion of a general price level concerns some index of prices in terms of a medium of account. -

A Study of Paul A. Samuelson's Economics

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. A Study of Paul A. Samuelson's Econol11ics: Making Economics Accessible to Students A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics at Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand. Leanne Marie Smith July 2000 Abstract Paul A. Samuelson is the founder of the modem introductory economics textbook. His textbook Economics has become a classic, and the yardstick of introductory economics textbooks. What is said to distinguish economics from the other social sciences is the development of a textbook tradition. The textbook presents the fundamental paradigms of the discipline, these gradually evolve over time as puzzles emerge, and solutions are found or suggested. The textbook is central to the dissemination of the principles of a discipline. Economics has, and does contribute to the education of students, and advances economic literacy and understanding in society. It provided a common economic language for students. Systematic analysis and research into introductory textbooks is relatively recent. The contribution that textbooks play in portraying a discipline and its evolution has been undervalued and under-researched. Specifically, applying bibliographical and textual analysis to textbook writing in economics, examining a single introductory economics textbook and its successive editions through time is new. When it is considered that an economics textbook is more than a disseminator of information, but a physical object with specific content, presented in a particular way, it changes the way a researcher looks at that textbook. -

Fiscal Policy in an Unemployment Crisis∗

Fiscal Policy in an Unemployment Crisis∗ Pontus Rendahly University of Cambridge, CEPR, and Centre for Macroeconomics (CFM) April 30, 2014 Abstract This paper shows that large fiscal multipliers arise naturally from equilibrium unemploy- ment dynamics. In response to a shock that brings the economy into a liquidity trap, an expansion in government spending increases output and causes a fall in the unemployment rate. Since movements in unemployment are persistent, the effects of current spending linger into the future, leading to an enduring rise in income. As an enduring rise in income boosts private demand, even a temporary increase in government spending sets in motion a virtuous employment-spending spiral with a large associated multiplier. This transmission mechanism contrasts with the conventional view in which fiscal policy may be efficacious only under a prolonged and committed rise in government spending, which engineers a spiral of increasing inflation. Keywords: Fiscal multiplier, liquidity trap, zero lower bound, unemployment inertia. ∗The first version of this paper can be found as Cambridge Working Papers in Economics No. 1211. yThe author would like to thank Andrea Caggese, Giancarlo Corsetti, Wouter den Haan, Jean-Paul L'Huillier, Giammario Impulitti, Karel Mertens, Emi Nakamura, Kristoffer Nimark, Evi Pappa, Franck Portier, Morten Ravn, Jon Steinsson, Silvana Tenreyro, and Mirko Wiederholt for helpful comments and suggestions. I am grateful to seminar participants at LSE, Royal Economic Society, UCL, European Univer- sity Institute, EIEF, ESSIM 2012, SED 2013, Bonn University, Goethe University, UAB, and in particular to James Costain, and Jonathan Heathcote for helpful discussions and conversations. Financial support is gratefully acknowledge from the Centre for Macroeconomics (CFM) and the Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET). -

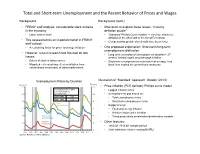

Total and Short-Term Unemployment and the Recent Behavior of Prices and Wages

Total and Short-term Unemployment and the Recent Behavior of Prices and Wages Background Background (cont.) • FRBNY staff analysis: considerable slack remains • Motivation to explore these issues: “missing in the economy deflation puzzle” • Labor market flows • “Standard” Phillips Curve models → very low inflation or deflation in the aftermath of the Great Recession • This assessment is an important factor in FRBNY • Compensation growth also should have been lower staff outlook • A restraining factor for price- and wage-inflation • One proposed explanation: Short-term/long-term unemployment distinction • However, recent research has focused on two • Long-term unemployed (unemployment duration > 27 issues: weeks): limited impact on price/wage inflation • Extent of slack in labor market • Short-term unemployment near historical average: less • Magnitude of restraining effect on inflation from slack than implied by conventional measures conventional measure(s) of labor market slack Unemployment Rates by Duration Illustration of “Standard” Approach: Gordon (2013) Percent Percent 12 12 • Price-inflation (PCE deflator) Phillips curve model: Correlation Between Short- • Lagged inflation terms term and Long-term 10 Unemployment 10 • Unemployment gap based on: 1976—2007 0.63 • Total unemployment rate 1976—2013 0.28 8 8 • Short-term unemployment rate Total Unemployment • Supply shocks: 6 6 • Food and energy inflation • Relative import price inflation 4 Short-term 4 • Trend productivity acceleration/deceleration variable Unemployment Long-term • Other features: 2 Unemployment 2 • 1960:Q1-2013:Q1 sample period 0 0 • Joint estimation of time-varying NAIRU 1976 1979 1982 1985 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 4 Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics Total and Short-term Unemployment and the Recent Behavior of Prices and Wages Evaluation of Short-term vs. -

Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions by Irving Fisher

THE DEBT-DEFLATION THEORY OF GREAT DEPRESSIONS BY IRVING FISHER INTRODUCTORY IN Booms and Depressions, I have developed, theoretically and sta- tistically, what may be called a debt-deflation theory of great depres- sions. In the preface, I stated that the results "seem largely new," I spoke thus cautiously because of my unfamiliarity with the vast literature on the subject. Since the book was published its special con- clusions have been widely accepted and, so far as I know, no one has yet found them anticipated by previous writers, though several, in- cluding myself, have zealously sought to find such anticipations. Two of the best-read authorities in this field assure me that those conclu- sions are, in the words of one of them, "both new and important." Partly to specify what some of these special conclusions are which are believed to be new and partly to fit them into the conclusions of other students in this field, I am offering this paper as embodying, in brief, my present "creed" on the whole subject of so-called "cycle theory." My "creed" consists of 49 "articles" some of which are old and some new. I say "creed" because, for brevity, it is purposely ex- pressed dogmatically and without proof. But it is not a creed in the sense that my faith in it does not rest on evidence and that I am not ready to modify it on presentation of new evidence. On the contrary, it is quite tentative. It may serve as a challenge to others and as raw material to help them work out a better product. -

Nber Working Paper Series Financial Markets and The

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES FINANCIAL MARKETS AND THE REAL ECONOMY John H. Cochrane Working Paper 11193 http://www.nber.org/papers/w11193 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2005 This review will introduce a volume by the same title in the Edward Elgar series “The International Library of Critical Writings in Financial Economics” edited by Richard Roll. I encourage comments. Please write promptly so I can include your comments in the final version. I gratefully acknowledge research support from the NSF in a grant administered by the NBER and from the CRSP. I thank Monika Piazzesi and Motohiro Yogo for comments. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2005 by John H. Cochrane. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Financial Markets and the Real Economy John H. Cochrane NBER Working Paper No. 11193 March 2005, Revised September 2006 JEL No. G1, E3 ABSTRACT I survey work on the intersection between macroeconomics and finance. The challenge is to find the right measure of "bad times," rises in the marginal value of wealth, so that we can understand high average returns or low prices as compensation for assets' tendency to pay off poorly in "bad times." I survey the literature, covering the time-series and cross-sectional facts, the equity premium, consumption-based models, general equilibrium models, and labor income/idiosyncratic risk approaches. -

Inflation and the Business Cycle

Inflation and the business cycle Michael McMahon Money and Banking (5): Inflation & Bus. Cycle 1 / 68 To Cover • Discuss the costs of inflation; • Investigate the relationship between money and inflation; • Introduce the Romer framework; • Discuss hyperinflations. • Shocks and the business cycle; • Monetary policy responses to business cycles. • Explain what the monetary transmission mechanism is; • Examine the link between inflation and GDP. Money and Banking (5): Inflation & Bus. Cycle 2 / 68 The Next Few Lectures Term structure, asset prices Exchange and capital rate market conditions Import prices Bank rate Net external demand CPI inflation Bank lending Monetary rates and credit Policy Asset purchase/ Corporate DGI conditions Framework sales demand loans Macro prudential Household policy demand deposits Inflation expectations Money and Banking (5): Inflation & Bus. Cycle 3 / 68 Inflation Definition Inflation is a sustained general rise in the price level in the economy. In reality we measure it using concepts such as: • Consumer Price Indices (CPI); • Producer Price Indices (PPI); • Deflators (GDP deflator, Consumption Expenditure Deflator) Money and Banking (5): Inflation & Bus. Cycle 4 / 68 Inflation: The Costs If all prices are rising at same rate, including wages and asset prices, what is the problem? • Information: Makes it harder to detect relative price changes and so hinders efficient operation of market; • Uncertainty: High inflation countries have very volatile inflation; • High inflation undermines role of money and encourages barter; • Growth - if inflation increases by 10%, reduce long term growth by 0.2% but only for countries with inflation higher than 15% (Barro); • Shoe leather costs/menu costs; • Interaction with tax system; • Because of fixed nominal contracts arbitrarily redistributes wealth; • Nominal contracts break down and long-term contracts avoided. -

A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960’

JOURNALOF Monetary ECONOMICS ELSEVIER Journal of Monetary Economics 34 (I 994) 5- 16 Review of Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz’s ‘A monetary history of the United States, 1867-1960’ Robert E. Lucas, Jr. Department qf Economics, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA (Received October 1993; final version received December 1993) Key words: Monetary history; Monetary policy JEL classijcation: E5; B22 A contribution to monetary economics reviewed again after 30 years - quite an occasion! Keynes’s General Theory has certainly had reappraisals on many anniversaries, and perhaps Patinkin’s Money, Interest and Prices. I cannot think of any others. Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz’s A Monetary History qf the United States has become a classic. People are even beginning to quote from it out of context in support of views entirely different from any advanced in the book, echoing the compliment - if that is what it is - so often paid to Keynes. Why do people still read and cite A Monetary History? One reason, certainly, is its beautiful time series on the money supply and its components, extended back to 1867, painstakingly documented and conveniently presented. Such a gift to the profession merits a long life, perhaps even immortality. But I think it is clear that A Monetary History is much more than a collection of useful time series. The book played an important - perhaps even decisive - role in the 1960s’ debates over stabilization policy between Keynesians and monetarists. It organ- ized nearly a century of U.S. macroeconomic evidence in a way that has had great influence on subsequent statistical and theoretical research. -

The Principle of Effective Demand and the State of Post Keynesian Monetary Economics

The University of Adelaide School of Economics Research Paper No. 2008-04 The Principle of Effective Demand and the State of Post Keynesian Monetary Economics Colin Rogers The principle of effective demand and the state of post Keynesian monetary economics Colin Rogers (Revised 20/08/08) School of Economics University of Adelaide Introduction Keynesians of all shades have generally misunderstood the theoretical structure of the General Theory. What is missing is an appreciation of the principle of effective demand. As Laidler (1999) has documented, Old Keynesians largely fabricated the theoretical basis of the Keynesian Revolution and retained the `classical' analysis of long-period equilibrium. Old Keynesians generally took Frank Knight's (1937) advice to ignore the claim to revolution in economic theory and interpreted the General Theory as another contribution to the theory of business cycles. This is most obvious from the Old Keynesian reliance on wage rigidity to generate involuntary unemployment. But for Keynes (1936, chapter 19), wage and price stickiness is the `classical' explanation for unemployment to be contrasted with his explanation, in terms of the principle of effective demand, where the flexibility of wages and prices cannot automatically shift long-period equilibrium to full employment. New Keynesians have continued the `classical' vision by providing the microeconomic foundations for the `ad hoc' rigidities employed by Old 1 Keynesians. Generally, New Keynesians do not question the underlying `classical' vision. Post Keynesians have always questioned the `classical' vision but have not succeeded as yet in agreeing on what the principle of effective demand is1. There should, however, be no grounds for misunderstanding of the principle of effective demand given Keynes's exposition in the General Theory and Dillard's (1948) synopsis. -

Dangers of Deflation Douglas H

ERD POLICY BRIEF SERIES Economics and Research Department Number 12 Dangers of Deflation Douglas H. Brooks Pilipinas F. Quising Asian Development Bank http://www.adb.org Asian Development Bank P.O. Box 789 0980 Manila Philippines 2002 by Asian Development Bank December 2002 ISSN 1655-5260 The views expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Asian Development Bank. The ERD Policy Brief Series is based on papers or notes prepared by ADB staff and their resource persons. The series is designed to provide concise nontechnical accounts of policy issues of topical interest to ADB management, Board of Directors, and staff. Though prepared primarily for internal readership within the ADB, the series may be accessed by interested external readers. Feedback is welcome via e-mail ([email protected]). ERD POLICY BRIEF NO. 12 Dangers of Deflation Douglas H. Brooks and Pilipinas F. Quising December 2002 ecently, there has been growing concern about deflation in some Rcountries and the possibility of deflation at the global level. Aggregate demand, output, and employment could stagnate or decline, particularly where debt levels are already high. Standard economic policy stimuli could become less effective, while few policymakers have experience in preventing or halting deflation with alternative means. Causes and Consequences of Deflation Deflation refers to a fall in prices, leading to a negative change in the price index over a sustained period. The fall in prices can result from improvements in productivity, advances in technology, changes in the policy environment (e.g., deregulation), a drop in prices of major inputs (e.g., oil), excess capacity, or weak demand. -

The Interaction Between Monetary and Fiscal Policy: Insights from Two Business Cycles in Israel

The interaction between monetary and fiscal policy: insights from two business cycles in Israel Kobi Braude and Karnit Flug1 Abstract Comparing the two significant recessions Israel experienced over the last decade, we highlight the importance of sustained fiscal discipline and credible monetary policy during normal times for expanding the set of policy options available at a time of need. In the first recession Israel was forced to conduct a contractionary fiscal and monetary policy, whereas in the second one it was able to pursue an expansionary policy. The difference in the effect of the policy response between the two recessions is sizable: it exacerbated the first recession while it helped to moderate the second one. Keywords: Fiscal policy, fiscal discipline, public debt, monetary policy, counter-cyclical policy, business cycles JEL classification: E52, E62, H6 1 Bank of Israel. We thank Stanley Fischer and Alon Binyamini for helpful comments and Noa Heymann for her research assistance. BIS Papers No 67 205 Introduction Over the last decade Israel experienced two significant business cycles. The monetary and fiscal policy response to the recession at the end of the decade was very different from the response to recession of the early 2000s. In the earlier episode, following a steep rise in the budget deficit and a single 2 percentage point interest rate reduction, policy makers were forced to make a sharp reversal and conduct a contractionary policy in the midst of the recession. In the second episode, monetary and fiscal expansion was pursued until recovery was well under way. This note examines the factors behind the difference in the policy response to the two recession episodes. -

New Keynesian Macroeconomics: Empirically Tested in the Case of Republic of Macedonia

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Josheski, Dushko; Lazarov, Darko Preprint New Keynesian Macroeconomics: Empirically tested in the case of Republic of Macedonia Suggested Citation: Josheski, Dushko; Lazarov, Darko (2012) : New Keynesian Macroeconomics: Empirically tested in the case of Republic of Macedonia, ZBW - Deutsche Zentralbibliothek für Wirtschaftswissenschaften, Leibniz-Informationszentrum Wirtschaft, Kiel und Hamburg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/64403 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu NEW KEYNESIAN MACROECONOMICS: EMPIRICALLY TESTED IN THE CASE OF REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA Dushko Josheski 1 Darko Lazarov2 Abstract In this paper we test New Keynesian propositions about inflation and unemployment trade off with the New Keynesian Phillips curve and the proposition of non-neutrality of money.