Reading Shakespearespread 5/21/09 9:53 AM Page 1 Reading Shakespeare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Pronunciation in Virginia

English Pronunciation in Virginia A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Virginia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for mavww-»~mn the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy -—wu_.<.=.- gr r-i ~ 7' - ‘ By EDWIN FRANCIS SHEWMAKE Alumni Professor of English in Davidson College _ ' UV; “Vtw ‘z 7 , ul’.m.‘;tl=-frmmfi.flmfiwuz_;_-I .- u~ 33915 . ._..,. PREFACE —. This study of English pronunciation in Virginia was accepted in 1920 by the faculty of the University of Virginia as a doctoral disserta- tion. That part dealing with the dialectal pronunciation of 0:4 and of i, was published in slightly modified form in Modern Language Notes, XL, 489 E., for December, 1925. The editor of the N ates has kindly given permission for the use of the article here. The author would thank all those who have in any way assisted or encouraged him in this undertaking. Especially does he wish to record his indebtedness to Professors John Calvin Metmlf and James Southall Wilson of the University of Virginia, Professor Percy W. Long of Harvard University, and Professor George Philip Krapp of Columbia University, all of whom have given valuable suggestions and advice. Thanks are also due to several editors and publishers for permission to use certain material for purposes of quotation and summary. The titles of books and periodicals used in this way appear in the text, with specific references to volumes and pages. E. F. S. Davidson, North Carolina. November, 1927. .-r.. .. _. .i 4.. ..._......_.__..4.-. .. >»~e~q—.«+.~vym oOpr-r 3-,, - A“. -

Applicant Preparation Guide for the Post Entry-Level Test Battery

APPLICANT PREPARATION GUIDE FOR THE POST ENTRY-LEVEL TEST BATTERY PREPARING FOR THE MULTIPLE-CHOICE AND CLOZE EXAMS There are many different types of tests. Two kinds of tests that most of us are familiar with are achievement tests and aptitude tests. Achievement tests measure what you know about some specific thing. A final exam in college is an example of an achievement test. In a final exam, the student is evaluated on how well he or she has mastered the curriculum of the class. Aptitude tests are quite different; they are tests for determining the probability of a person's success in some activity in which he or she is not yet trained. A college entrance test, such as the SAT, is an example of an aptitude test. In reality, achievement tests and aptitude tests occupy the end points of a continuum of test type for all tests are a little of each. It is important to know the distinction between the two types of tests is because, in general, you can study to improve your score on an achievement test, but there is only a limited amount of study and preparation that you can do for an aptitude test. The POST Test-Battery is primarily a language aptitude test. As such, there is some improvement in test score that can be achieved by preparation, but how you do on the test is primarily determined by how much language skill you presently possess. Language skills develop over a lifetime and tend to be very stable. Noticeable improvement in language skills typically takes a prolonged, intense effort. -

Open Steinle Cory Kanyecriticism.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION ARTS & SCIENCES “I THOUGHT ABOUT KILLING YOU”: CONSIDERING THE UTILITY OF RHETORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL CRITICAL APPROACHES TO KANYE WEST’S YE CORY N. STEINLE SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Communication Arts and Sciences and Labor and Employment Relations with honors in Communication Arts and Sciences Reviewed and approved* by the following: Bradford Vivian Professor of Communication Arts & Sciences Thesis Supervisor Lori Bedell Associate Teaching Professor in Communication Arts & Sciences Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT This paper examines the merits of intrinsic and extrinsic critical approaches to hip-hop artifacts. To do so, I provide both a neo-Aristotelian and biographical criticism of three songs from ye (2018) by Kanye West. Chapters 1 & 2 consider Roland Barthes’ The Death of the Author and other landmark papers in rhetorical and literary theory to develop an intrinsic and extrinsic approach to criticizing ye (2018), evident in Tables 1 & 2. Chapter 3 provides the biographical antecedents of West’s life prior to the release of ye (2018). Chapters 4, 5, & 6 supply intrinsic (neo-Aristotelian) and extrinsic (biographical) critiques of the selected artifacts. Each of these chapters aims to address the concerns of one of three guiding questions: which critical approaches prove most useful to the hip-hop consumer listening to this song? How can and should the listener construct meaning? Are there any improper ways to critique and interpret this song? Chapter 7 discusses the variance in each mode of critical analysis from Chapters 4, 5, & 6. -

In Because of Mr. Terupt by Rob Buyea Content

Content Questions Question Answer Pg # In Because of Mr. Terupt by Rob Buyea What grade does Mr Terupt teach? 5th grade 1 What month does Because of Mr. Terupt start? September 1 What kind of teacher is the best hope to get? Brand-new 1 Which character first narrates BOMT? Peter 1 What grade is Peter entering? Fifth 1 What is the name of the rookie teacher? Mr. Terupt 1 Where does Peter go to get out of doing work? The bathrooms 1 Where are the bathrooms located? Right across the hall 1 What did Peter's brother say you would have to clean the A tooth brush 2 toilets with if you got caught plugging them with toilet paper? Who is the pirncipal? Mrs. Williams 2 What are the two nicknames Mr. Terupt wanted to give Peter Mr. Peebody Pee-er 2 for using the restroom? What table did Peter sit at? Number Three 3 Who sat right next to Peter? Marty 3 What is the name of the school where Mr Terupt teaches? Snow Hill School 4 What was the name of the school? Snow Hill School 4 What state does the book take place? Connecticut 4 What color hair does Mr.s Williams have? Brown 4 Who is Jessica's Mom? Julie Whiteman 4 Two part question: What is the name of Jessica's new school Snow Hill School AND Mrs. Williams. 5 and who is the principal? Where is Jessica from? California 5 Where is Jessica's dad? California 5 What does Jessica's dad do? Write plays 5 1 Content Questions Question Answer Pg # In Because of Mr. -

Two-Words.Pdf

TWO WORDS by Isabel Allende Copyright © 1989 by Isabel Allende https://fortheloveofshortstories.wordpress.com/2016/09/01/two-words/ She went by the name of Belisa Crepusculario, not because she had been baptized with that name or given it by her mother, but because she herself had searched until she found the poetry of "beauty" and "twilight" and cloaked herself in it. She made her living selling words. She journeyed through the country from the high cold mountains to the burning coasts, stopping at fairs and in markets where she set up four poles covered by a canvas awning under which she took refuge from the sun and rain to minister to her customers. She did not have to peddle her merchandise because from having wandered far and near, everyone knew who she was. Some people waited for her from one year to the next, and when she appeared in the village with her bundle beneath her arm, they would form a line in front of her stall. Her prices were fair. For five centavos she delivered verses from memory, for seven she improved the quality of dreams, for nine she wrote love letters, for twelve she invented insults for irreconcilable enemies. She also sold stories, not fantasies but long, true stories she recited at one telling, never skipping a word. This is how she carried news from one town to another. People paid her to add a line or two: our son was born, so-and-so died, our children got married, the crops burned in the field. Wherever she went a small crowd gathered around to listen as she began to speak, and that was how they learned about each others' doings, about distant relatives, about what was going on in the civil war. -

Beginning Japanese for Professionals: Book 1

BEGINNING JAPANESE FOR PROFESSIONALS: BOOK 1 Emiko Konomi Beginning Japanese for Professionals: Book 1 Emiko Konomi Portland State University 2015 ii © 2018 Emiko Konomi This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License You are free to: • Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format • Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. Under the following terms: • Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. • NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes Published by Portland State University Library Portland, OR 97207-1151 Cover photo: courtesy of Katharine Ross iii Accessibility Statement PDXScholar supports the creation, use, and remixing of open educational resources (OER). Portland State University (PSU) Library acknowledges that many open educational resources are not created with accessibility in mind, which creates barriers to teaching and learning. PDXScholar is actively committed to increasing the accessibility and usability of the works we produce and/or host. We welcome feedback about accessibility issues our users encounter so that we can work to mitigate them. Please email us with your questions and comments at [email protected]. “Accessibility Statement” is a derivative of Accessibility Statement by BCcampus, and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Accessibility of Beginning Japanese I A prior version of this document contained multiple accessibility issues. -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia ) Robert R. Prunté, )

Case 1:06-cv-00480-PLF Document 116 Filed 03/29/10 Page 1 of 24 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA __________________________________________ ) ROBERT R. PRUNTÉ, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 06-0480 (PLF) ) UNIVERSAL MUSIC GROUP, INC., et al., ) ) Defendants. ) __________________________________________) OPINION Plaintiff Robert R. Prunté alleges that approximately 45 named defendants have infringed his copyright in numerous songs that he wrote and produced. He seeks to recover damages pursuant to the Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. §§ 101 et seq., for direct and contributory copyright violations. Of the many defendants currently named in this case, only two — UMG Recordings, Inc. (“UMG” or “Universal”), and Warner Music Group Corp. (“Warner”) (collectively “the defendants”), have responded to the complaint. These defendants have filed a motion for summary judgment, and Mr. Prunté has filed a cross-motion. Mr. Prunté has also submitted two plainly frivolous motions in which he (1) alleges that the defendants are in contempt of court, and (2) requests that the Court “take judicial notice of certain adjudicative facts and facts of law.” Docket No. 94 at 1. The defendants have moved to strike various papers Case 1:06-cv-00480-PLF Document 116 Filed 03/29/10 Page 2 of 24 filed by Mr. Prunté, including his motion alleging contempt of court and his motion for summary judgment.1 Upon consideration of the entire record in this case, the parties’ arguments, and the relevant law, the Court concludes that the defendants’ works are not substantially similar to those of the plaintiff and that the defendants therefore are entitled to summary judgment on all claims. -

Word Choice (Denotation and Connotation)

Word Choice (Denotation and Connotation) In argumentative writing, as in an editorial, authors choose their words carefully in order to best convince the audience of his/her point of view. They try to pick the most precise words to create the proper tone for their message. The way they achieve this effect is to write with words that have attached to them certain denotations and connotations. Denotation-Dictionary, literal meaning of words Connotation-Common associations that people make with words (positive or negative) Example Word: Gray Denotation-Color of any shade between the colors of black and white Connotation-Negative, Gloom, Sadness, Old Age Practice Word: Mustang Denotation-Small, wild horse of the North American Plains Connotation-Positive, strong, fast, sleek, beautiful The connotation of the word is why Ford carmakers would choose to name one of its models “Mustang.” Think of two currently used automobile names. What are the denotations of the words? What connotations did the manufacturer hope to evoke in naming that car that particular name? What details do the names bring to mind? What does the name tell you about who drives the car, how fast it is, and what its features are? Denotation and Connotation Practice Car #1 Car #2 Automobile Name: Denotation: Connotations: What name tells you about driver, speed, features of car: Now think of a car and color that describe you. Be prepared to share your response with the class. Car: Features of car that are similar to you: Color: Reason for color of car: Connotation Practice Words with similar dictionary meanings often have different connotations, so it is very important for a writer to choose words carefully. -

Possessive Contraction Pronoun Adverb It + Is = It's Its You + Are = You're Your He = Is = He's His They + Are = They're Their There Who + Is = Who's Whose

42 Name _ Date _ Contraction or Possessive Pronoun? I . Possessive Contraction Pronoun Adverb it + is = it's its you + are = you're your he = is = he's his they + are = they're their there who + is = who's whose Please select the proper word. l. The dog ate (it's, its) dinner. 2. (It' s, Its) going to rain tomorrow. 3. The team elected (it's, its) captain. 4. The man said that (it's, its) too hot to play baseball. 5. (You're, Your) studying apostrophes in this lesson. 6. (You're, Your) book is on the table. 7. If (you're, your) ready, you may begin the test. 8. Please give me (you're, your) opinion. 9. Tom said that (he's, his) lost his new iPod. 10. Jerry will lend you (he's, his) book tomorrow. 11. (Their, There, They're) going to win the game! 12. (Their, There, They're) children are at the party. 13. (Their, There, They're) goes my new car! 14. The Smiths borrowed my car. (Their, There, They're) car is in the shop. 15. It was Mr. Lee (whose, who's) car was stolen. 16. (Whose, Who's) going to the soccer game? 17. (Whose, Who's) book is this? 18. Karen was the teacher (whose, who's) book was chosen to be published. 43 Name _ Dme _ Adjective or Adverb? Please review each sentence carefully and choose the appropriate word. I. Always drive (careful, carefully). 2. Be (careful, carefully)! 3. Sara waited (patient, patiently) for class. 4. -

TABOOS – Common Writing Errors to Avoid (Created by Philip Dacey, SMSU Professor Emeritus, 1939-2016)

TABOOS – Common Writing Errors to Avoid (Created by Philip Dacey, SMSU Professor Emeritus, 1939-2016) Professor Marianne Murphy Zarzana Southwest Minnesota State University, Marshall, Minnesota The errors identified below are ones students frequently make. Writing well is, of course, not just a matter of avoiding errors, but an error-free paper is like a clean window through which the reader looks; it helps display clearly what you have to say. Errors say, “I don’t care enough about you to take pains with this communication.” Ideally, over the course of the semester, you will not be violating any of these taboos and will have moved on to more advanced considerations about writing, positive ones, not just what to avoid but what to do to enhance your work. (On your essays, T plus a number will indicate one of the following taboos.) “We live at the level of our language. Whatever we can articulate we can imagine or understand or explore.” – Ellen Gilchrist I. GRAMMAR 1. Be wary of like/as confusion. “Like” is a preposition and must take an object: he looks like trouble. “Like” cannot precede a clause (clauses, unlike phrases, have verbs); “as” can precede a clause because it’s a conjunction. “Winston tastes good like a cigarette should” is grammatically incorrect (as the ad writers knew). Sometimes “that” can replace “like”: I feel alone, (like) that nobody cares.” Or try “as if.” 2. “Then,” “thus,” and “therefore” are adverbs, not conjunctions, and therefore cannot connect two independent clauses, even with a comma. Not this: “He knocked on the door, then she came to the window.” One alternative is: “When he knocked on the door, she came, etc.” 3. -

STC Macbeth's.Idml

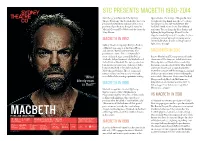

STC PRESENTS MACBETH 1980-2014 Over the 34-year-history of the Sydney Opera House. The design of the production Theatre Company “the Scottish play” has been brought the play fi rmly into the 20th century produced seven times, making it STC’s most by taking on a desolate World War I-like performed production, alongside Away by battlefi eld with actors dressed in military Michael Gow and Two Weeks with the Queen by uniforms. The set design by John Gunter and Mary Morris. lighting by Nigel Levings allowed for the stage to seamlessly morph from place to place creating a sinister atmosphere using arrow MACBETH IN 1982 slits in walls where shards and fragments of light shone through. Sydney Theatre Company’s fi rst production of Macbeth was staged at the Opera House and directed by Richard Wherrett. The MACHOMER IN 2010 performance starred three of Australia’s most celebrated stage actors, John Bell as In 2010 Macbeth at STC was performed by the Macbeth, Robyn Nevin as Lady Macbeth and characters of The Simpsons, titled MacHomer. Colin Friels as Macduff. The 1982 production This adaptation of Macbeth was created by had directorial references of character links Canadian comedian Rick Miller who in his between Macbeth and Hamlet and Lady one man show took on 50 characters Macbeth and Ophelia. The set design had from the cartoon while wearing traditional terracotta hues and was a series of rough, Shakespearean costume and mimicking the “What monolithic slabs creating a primitive setting. voices of the characters. Homer was Macbeth, bloody man Marge was Lady Macbeth, Mr Burns was MACBETH IN 1996 King Duncan and Barney was Macduff. -

DUNS Program5 FINAL Lowres

DUNSINANE DUNSINANE Contents —The Merry Wives of Windsor Chicago Shakespeare Theater 800 E. Grand on Navy Pier On the Boards 8 Chicago, Illinois 60611 A selection of notable CST events, plays and players 312.595.5600 www.chicagoshakes.com ©2015 Point of View 10 Chicago Shakespeare Theater Joyce McMillan examines the truth in All rights reserved. Shakespeare’s storytelling artistic director: Barbara Gaines executive director: Criss Henderson Cast 17 cover: Siobhan Redmond and Darrell D’Silva, photo by Simon Murphy. above: Siobhan Redmond in Dunsinane, photo by Richard Campbell. Playgoer’s Guide 18 Profiles 20 From Another Perspective 32 Journalist Jackie McGlone discusses Dunsinane playwright David Greig’s historical and contemporary inspirations www.chicagoshakes.com 3 CHICAGO SHAKESPEARE THEATER To be! Welcome DEAR FRIENDS, Welcome to Chicago’s home for Shakespeare. Today’s presentation marks the return of two of our seminal international partners: the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre of Scotland. Their collaboration on Dunsinane has created a tour-de-force, penned by modern-day Scottish playwright David Greig. By boldly imaging the complicated power struggle following the demise of King Macbeth, Greig provokes a timely dialog on the complexities of nation- building following an invasion of epic proportion. The original play is one of the greatest tragedies ever written. To have it followed 400 years later by an equally complicated, nuanced tale is theatrically thrilling. Through our World’s Stage Series, we are honored to serve as a cultural ambassador by importing leading international companies like the RSC and National Theatre of Scotland to Chicago. In the spirit of cultural exchange, we are also increasingly exporting our own work to the world.