Mutations in NGLY1 Cause an Inherited Disorder of the Endoplasmic Reticulum–Associated Degradation Pathway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Science

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Science. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2014 September 08. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Science. 2014 January 31; 343(6170): 506–511. doi:10.1126/science.1247363. Exome Sequencing Links Corticospinal Motor Neuron Disease to Common Neurodegenerative Disorders A full list of authors and affiliations appears at the end of the article. # These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract Hereditary spastic paraplegias (HSPs) are neurodegenerative motor neuron diseases characterized by progressive age-dependent loss of corticospinal motor tract function. Although the genetic basis is partly understood, only a fraction of cases can receive a genetic diagnosis, and a global view of HSP is lacking. By using whole-exome sequencing in combination with network analysis, we identified 18 previously unknown putative HSP genes and validated nearly all of these genes functionally or genetically. The pathways highlighted by these mutations link HSP to cellular transport, nucleotide metabolism, and synapse and axon development. Network analysis revealed a host of further candidate genes, of which three were mutated in our cohort. Our analysis links HSP to other neurodegenerative disorders and can facilitate gene discovery and mechanistic understanding of disease. Hereditary spastic paraplegias (HSPs) are a group of genetically heterogeneous neurodegenerative disorders with prevalence between 3 and 10 per 100,000 individuals (1). Hallmark features are axonal degeneration and progressive lower limb spasticity resulting from a loss of corticospinal tract (CST) function. HSP is classified into two broad categories, uncomplicated and complicated, on the basis of the presence of additional clinical features such as intellectual disability, seizures, ataxia, peripheral neuropathy, skin abnormalities, and visual defects. -

2020 Program Book

PROGRAM BOOK Note that TAGC was cancelled and held online with a different schedule and program. This document serves as a record of the original program designed for the in-person meeting. April 22–26, 2020 Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center Metro Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS About the GSA ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Conference Organizers ...........................................................................................................................................4 General Information ...............................................................................................................................................7 Mobile App ....................................................................................................................................................7 Registration, Badges, and Pre-ordered T-shirts .............................................................................................7 Oral Presenters: Speaker Ready Room - Camellia 4.......................................................................................7 Poster Sessions and Exhibits - Prince George’s Exhibition Hall ......................................................................7 GSA Central - Booth 520 ................................................................................................................................8 Internet Access ..............................................................................................................................................8 -

2021 Western Medical Research Conference

Abstracts J Investig Med: first published as 10.1136/jim-2021-WRMC on 21 December 2020. Downloaded from Genetics I Purpose of Study Genomic sequencing has identified a growing number of genes associated with developmental brain disorders Concurrent session and revealed the overlapping genetic architecture of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and intellectual disability (ID). Chil- 8:10 AM dren with ASD are often identified first by psychologists or neurologists and the extent of genetic testing or genetics refer- Friday, January 29, 2021 ral is variable. Applying clinical whole genome sequencing (cWGS) early in the diagnostic process has the potential for timely molecular diagnosis and to circumvent the diagnostic 1 PROSPECTIVE STUDY OF EPILEPSY IN NGLY1 odyssey. Here we report a pilot study of cWGS in a clinical DEFICIENCY cohort of young children with ASD. RJ Levy*, CH Frater, WB Galentine, MR Ruzhnikov. Stanford University School of Medicine, Methods Used Children with ASD and cognitive delays/ID Stanford, CA were referred by neurologists or psychologists at a regional healthcare organization. Medical records were used to classify 10.1136/jim-2021-WRMC.1 probands as 1) ASD/ID or 2) complex ASD (defined as 1 or more major malformations, abnormal head circumference, or Purpose of Study To refine the electroclinical phenotype of dysmorphic features). cWGS was performed using either epilepsy in NGLY1 deficiency via prospective clinical and elec- parent-child trio (n=16) or parent-child-affected sibling (multi- troencephalogram (EEG) findings in an international cohort. plex families; n=3). Variants were classified according to Methods Used We performed prospective phenotyping of 28 ACMG guidelines. -

A Drosophila Natural Variation Screen Identifies NKCC1 As a Substrate of NGLY1 Deglycosylation and a Modifier of NGLY1 Deficienc

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.13.039651; this version posted April 14, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Title 2 A Drosophila natural variation screen identifies NKCC1 as a substrate of NGLY1 deglycosylation 3 and a modifier of NGLY1 deficiency 4 Authors 5 Dana M. Talsness1, Katie G. Owings1, Emily Coelho1, Gaelle Mercenne2, John M. Pleinis2, Aamir 6 R. Zuberi3, Raghavendran Partha4, Nathan L. Clark1, Cathleen M. Lutz3, Aylin R. Rodan2,5, 7 Clement Y. Chow1* 8 The first two authors contributed equally to this study. 1Department of Human Genetics, University 9 of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, UT; 2Department of Internal Medicine, Division of 10 Nephrology and Hypertension, and Molecular Medicine Program, University of Utah, Salt Lake 11 City, UT; 3Genetic Resource Science, The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME.; 4Department of 12 Computational and Systems Biology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA; 5Medical Service, 13 Veterans Affairs Salt Lake City Health Care System, Salt Lake City, UT; *For correspondence: 14 [email protected] 15 Abstract 16 N-Glycanase 1 (NGLY1) is a cytoplasmic deglycosylating enzyme. Loss-of-function mutations in 17 the NGLY1 gene cause NGLY1 deficiency, which is characterized by developmental delay, 18 seizures, and a lack of sweat and tears. To model the phenotypic variability observed among 19 patients, we crossed a Drosophila model of NGLY1 deficiency onto a panel of genetically diverse 20 strains. -

Mouse Ngly1 Conditional Knockout Project (CRISPR/Cas9)

https://www.alphaknockout.com Mouse Ngly1 Conditional Knockout Project (CRISPR/Cas9) Objective: To create a Ngly1 conditional knockout Mouse model (C57BL/6J) by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Strategy summary: The Ngly1 gene (NCBI Reference Sequence: NM_021504 ; Ensembl: ENSMUSG00000021785 ) is located on Mouse chromosome 14. 12 exons are identified, with the ATG start codon in exon 1 and the TGA stop codon in exon 12 (Transcript: ENSMUST00000022310). Exon 2 will be selected as conditional knockout region (cKO region). Deletion of this region should result in the loss of function of the Mouse Ngly1 gene. To engineer the targeting vector, homologous arms and cKO region will be generated by PCR using BAC clone RP23-304N3 as template. Cas9, gRNA and targeting vector will be co-injected into fertilized eggs for cKO Mouse production. The pups will be genotyped by PCR followed by sequencing analysis. Note: Mice homozygous for a knock-out allele exhibit dysregulation of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation (ERAD) process. Exon 2 starts from about 6.76% of the coding region. The knockout of Exon 2 will result in frameshift of the gene. The size of intron 1 for 5'-loxP site insertion: 5144 bp, and the size of intron 2 for 3'-loxP site insertion: 5807 bp. The size of effective cKO region: ~615 bp. The cKO region does not have any other known gene. Page 1 of 8 https://www.alphaknockout.com Overview of the Targeting Strategy Wildtype allele gRNA region 5' gRNA region 3' 1 2 12 Targeting vector Targeted allele Constitutive KO allele (After Cre recombination) Legends Exon of mouse Ngly1 Homology arm cKO region loxP site Page 2 of 8 https://www.alphaknockout.com Overview of the Dot Plot Window size: 10 bp Forward Reverse Complement Sequence 12 Note: The sequence of homologous arms and cKO region is aligned with itself to determine if there are tandem repeats. -

Ubiquitin-Dependent Regulation of the WNT Cargo Protein EVI/WLS Handelt Es Sich Um Meine Eigenständig Erbrachte Leistung

DISSERTATION submitted to the Combined Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics of the Ruperto-Carola University of Heidelberg, Germany for the degree of Doctor of Natural Sciences presented by Lucie Magdalena Wolf, M.Sc. born in Nuremberg, Germany Date of oral examination: 2nd February 2021 Ubiquitin-dependent regulation of the WNT cargo protein EVI/WLS Referees: Prof. Dr. Michael Boutros apl. Prof. Dr. Viktor Umansky If you don’t think you might, you won’t. Terry Pratchett This work was accomplished from August 2015 to November 2020 under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Michael Boutros in the Division of Signalling and Functional Genomics at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany. Contents Contents ......................................................................................................................... ix 1 Abstract ....................................................................................................................xiii 1 Zusammenfassung .................................................................................................... xv 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 2.1 The WNT signalling pathways and cancer ........................................................................ 1 2.1.1 Intercellular communication ........................................................................................ 1 2.1.2 WNT ligands are conserved morphogens ................................................................. -

MOCHI Enables Discovery of Heterogeneous Interactome Modules in 3D Nucleome

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 4, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press MOCHI enables discovery of heterogeneous interactome modules in 3D nucleome Dechao Tian1,# , Ruochi Zhang1,# , Yang Zhang1, Xiaopeng Zhu1, and Jian Ma1,* 1Computational Biology Department, School of Computer Science, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA #These two authors contributed equally *Correspondence: [email protected] Contact To whom correspondence should be addressed: Jian Ma School of Computer Science Carnegie Mellon University 7705 Gates-Hillman Complex 5000 Forbes Avenue Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Phone: +1 (412) 268-2776 Email: [email protected] 1 Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 4, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Abstract The composition of the cell nucleus is highly heterogeneous, with different constituents forming complex interactomes. However, the global patterns of these interwoven heterogeneous interactomes remain poorly understood. Here we focus on two different interactomes, chromatin interaction network and gene regulatory network, as a proof-of-principle, to identify heterogeneous interactome modules (HIMs), each of which represents a cluster of gene loci that are in spatial contact more frequently than expected and that are regulated by the same group of transcription factors. HIM integrates transcription factor binding and 3D genome structure to reflect “transcriptional niche” in the nucleus. We develop a new algorithm MOCHI to facilitate the discovery of HIMs based on network motif clustering in heterogeneous interactomes. By applying MOCHI to five different cell types, we found that HIMs have strong spatial preference within the nucleus and exhibit distinct functional properties. Through integrative analysis, this work demonstrates the utility of MOCHI to identify HIMs, which may provide new perspectives on the interplay between transcriptional regulation and 3D genome organization. -

Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia: from Genes, Cells and Networks to Novel Pathways for Drug Discovery

brain sciences Review Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia: From Genes, Cells and Networks to Novel Pathways for Drug Discovery Alan Mackay-Sim Griffith Institute for Drug Discovery, Griffith University, Brisbane, QLD 4111, Australia; a.mackay-sim@griffith.edu.au Abstract: Hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) is a diverse group of Mendelian genetic disorders affect- ing the upper motor neurons, specifically degeneration of their distal axons in the corticospinal tract. Currently, there are 80 genes or genomic loci (genomic regions for which the causative gene has not been identified) associated with HSP diagnosis. HSP is therefore genetically very heterogeneous. Finding treatments for the HSPs is a daunting task: a rare disease made rarer by so many causative genes and many potential mutations in those genes in individual patients. Personalized medicine through genetic correction may be possible, but impractical as a generalized treatment strategy. The ideal treatments would be small molecules that are effective for people with different causative mutations. This requires identification of disease-associated cell dysfunctions shared across geno- types despite the large number of HSP genes that suggest a wide diversity of molecular and cellular mechanisms. This review highlights the shared dysfunctional phenotypes in patient-derived cells from patients with different causative mutations and uses bioinformatic analyses of the HSP genes to identify novel cell functions as potential targets for future drug treatments for multiple genotypes. Keywords: neurodegeneration; motor neuron disease; spastic paraplegia; endoplasmic reticulum; Citation: Mackay-Sim, A. Hereditary protein-protein interaction network Spastic Paraplegia: From Genes, Cells and Networks to Novel Pathways for Drug Discovery. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 403. -

Regulation of BMP4/Dpp Retrotranslocation and Signaling By

RESEARCH ADVANCE Regulation of BMP4/Dpp retrotranslocation and signaling by deglycosylation Antonio Galeone1,2, Joshua M Adams3,4, Shinya Matsuda5, Maximiliano F Presa6, Ashutosh Pandey1, Seung Yeop Han1, Yuriko Tachida7,8, Hiroto Hirayama7,8, Thomas Vaccari2, Tadashi Suzuki7,8, Cathleen M Lutz6, Markus Affolter5, Aamir Zuberi6, Hamed Jafar-Nejad1,3* 1Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, United States; 2Department of Biosciences, University of Milan, Milan, Italy; 3Program in Developmental Biology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, United States; 4Medical Scientist Training Program, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, United States; 5Biozentrum, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland; 6The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, United States; 7Glycometabolome Biochemistry Laboratory, RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research, Saitama, Japan; 8T-CiRA joint program, Kanagawa, Japan Abstract During endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD), the cytoplasmic enzyme N-glycanase 1 (NGLY1) is proposed to remove N-glycans from misfolded N-glycoproteins after their retrotranslocation from the ER to the cytosol. We previously reported that NGLY1 regulates Drosophila BMP signaling in a tissue-specific manner (Galeone et al., 2017). Here, we establish the Drosophila Dpp and its mouse ortholog BMP4 as biologically relevant targets of NGLY1 and find, unexpectedly, that NGLY1-mediated deglycosylation of misfolded BMP4 is required for its *For correspondence: retrotranslocation. Accumulation of misfolded BMP4 in the ER results in ER stress and prompts the [email protected] ER recruitment of NGLY1. The ER-associated NGLY1 then deglycosylates misfolded BMP4 molecules to promote their retrotranslocation and proteasomal degradation, thereby allowing Competing interests: The properly-folded BMP4 molecules to proceed through the secretory pathway and activate signaling authors declare that no competing interests exist. -

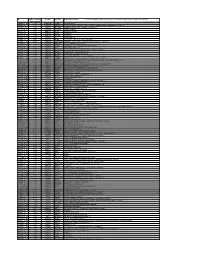

ID AKI Vs Control Fold Change P Value Symbol Entrez Gene Name *In

ID AKI vs control P value Symbol Entrez Gene Name *In case of multiple probesets per gene, one with the highest fold change was selected. Fold Change 208083_s_at 7.88 0.000932 ITGB6 integrin, beta 6 202376_at 6.12 0.000518 SERPINA3 serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade A (alpha-1 antiproteinase, antitrypsin), member 3 1553575_at 5.62 0.0033 MT-ND6 NADH dehydrogenase, subunit 6 (complex I) 212768_s_at 5.50 0.000896 OLFM4 olfactomedin 4 206157_at 5.26 0.00177 PTX3 pentraxin 3, long 212531_at 4.26 0.00405 LCN2 lipocalin 2 215646_s_at 4.13 0.00408 VCAN versican 202018_s_at 4.12 0.0318 LTF lactotransferrin 203021_at 4.05 0.0129 SLPI secretory leukocyte peptidase inhibitor 222486_s_at 4.03 0.000329 ADAMTS1 ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 1 1552439_s_at 3.82 0.000714 MEGF11 multiple EGF-like-domains 11 210602_s_at 3.74 0.000408 CDH6 cadherin 6, type 2, K-cadherin (fetal kidney) 229947_at 3.62 0.00843 PI15 peptidase inhibitor 15 204006_s_at 3.39 0.00241 FCGR3A Fc fragment of IgG, low affinity IIIa, receptor (CD16a) 202238_s_at 3.29 0.00492 NNMT nicotinamide N-methyltransferase 202917_s_at 3.20 0.00369 S100A8 S100 calcium binding protein A8 215223_s_at 3.17 0.000516 SOD2 superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial 204627_s_at 3.04 0.00619 ITGB3 integrin, beta 3 (platelet glycoprotein IIIa, antigen CD61) 223217_s_at 2.99 0.00397 NFKBIZ nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, zeta 231067_s_at 2.97 0.00681 AKAP12 A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 12 224917_at 2.94 0.00256 VMP1/ mir-21likely ortholog -

Download Ppis for Each Single Seed, Thus Obtaining Each Seed’S Interactome (Ferrari Et Al., 2018)

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.14.425874; this version posted January 16, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Integrating protein networks and machine learning for disease stratification in the Hereditary Spastic Paraplegias Nikoleta Vavouraki1,2, James E. Tomkins1, Eleanna Kara3, Henry Houlden3, John Hardy4, Marcus J. Tindall2,5, Patrick A. Lewis1,4,6, Claudia Manzoni1,7* Author Affiliations 1: Department of Pharmacy, University of Reading, Reading, RG6 6AH, United Kingdom 2: Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Reading, Reading, RG6 6AH, United Kingdom 3: Department of Neuromuscular Diseases, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, WC1N 3BG, United Kingdom 4: Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, WC1N 3BG, United Kingdom 5: Institute of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Research, University of Reading, Reading, RG6 6AS, United Kingdom 6: Department of Comparative Biomedical Sciences, Royal Veterinary College, London, NW1 0TU, United Kingdom 7: School of Pharmacy, University College London, London, WC1N 1AX, United Kingdom *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract The Hereditary Spastic Paraplegias are a group of neurodegenerative diseases characterized by spasticity and weakness in the lower body. Despite the identification of causative mutations in over 70 genes, the molecular aetiology remains unclear. Due to the combination of genetic diversity and variable clinical presentation, the Hereditary Spastic Paraplegias are a strong candidate for protein- protein interaction network analysis as a tool to understand disease mechanism(s) and to aid functional stratification of phenotypes. -

ER-Resident Transcription Factor Nrf1 Regulates Proteasome Expression and Beyond

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review ER-Resident Transcription Factor Nrf1 Regulates Proteasome Expression and Beyond Jun Hamazaki * and Shigeo Murata Laboratory of Protein Metabolism, Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, the University of Tokyo, Tokyo 1130033, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 4 May 2020; Accepted: 20 May 2020; Published: 23 May 2020 Abstract: Protein folding is a substantively error prone process, especially when it occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The highly exquisite machinery in the ER controls secretory protein folding, recognizes aberrant folding states, and retrotranslocates permanently misfolded proteins from the ER back to the cytosol; these misfolded proteins are then degraded by the ubiquitin–proteasome system termed as the ER-associated degradation (ERAD). The 26S proteasome is a multisubunit protease complex that recognizes and degrades ubiquitinated proteins in an ATP-dependent manner. The complex structure of the 26S proteasome requires exquisite regulation at the transcription, translation, and molecular assembly levels. Nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-related factor 1 (Nrf1; NFE2L1), an ER-resident transcription factor, has recently been shown to be responsible for the coordinated expression of all the proteasome subunit genes upon proteasome impairment in mammalian cells. In this review, we summarize the current knowledge regarding the transcriptional regulation of the proteasome, as well as recent findings concerning the regulation of Nrf1 transcription activity in ER homeostasis and metabolic processes. Keywords: proteasome; Nrf1; DDI2; bounce back; proteostasis 1. Introduction Proteins are essential to the vast majority of cellular and organismal functions. Cellular protein levels are defined by the balance among protein synthesis, folding, and degradation, and the failure to accurately coordinate these processes leads to disease [1].