Entanglements a Story Mapping Tool for Rpgs Version 0.2 ©2011 by Ewen Cluney

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARCH 1St 2018

March 1st We love you, Archivist! MARCH 1st 2018 Attention PDF authors and publishers: Da Archive runs on your tolerance. If you want your product removed from this list, just tell us and it will not be included. This is a compilation of pdf share threads since 2015 and the rpg generals threads. Some things are from even earlier, like Lotsastuff’s collection. Thanks Lotsastuff, your pdf was inspirational. And all the Awesome Pioneer Dudes who built the foundations. Many of their names are still in the Big Collections A THOUSAND THANK YOUS to the Anon Brigade, who do all the digging, loading, and posting. Especially those elite commandos, the Nametag Legionaires, who selflessly achieve the improbable. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – The New Big Dog on the Block is Da Curated Archive. It probably has what you are looking for, so you might want to look there first. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – Don't think of this as a library index, think of it as Portobello Road in London, filled with bookstores and little street market booths and you have to talk to each shopkeeper. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to ~16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. Some links are encoded without a hyperlink to restrict spiderbot activity. You will have to complete the link. Sorry for the inconvenience. Others are encoded but have a working hyperlink underneath. Some are Spoonerisms or even written backwards, Enjoy! ss, @SS or $$ is Send Spaace, m3g@ is Megaa, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. -

The Platinum Appendix

SHANNON APPELCLINE SHANNON A HISTORY OF THE ROLEPLAYING GAME INDUSTRY THE PLATINUM APPENDIX SHANNON APPELCLINE This supplement to the Designers & Dragons book series was made possible by the incredible support given to us by the backers of the Designers & Dragons Kickstarter campaign. To all our backers, a big thank you from Evil Hat! _Journeyman_ Antoine Pempie Carlos Curt Meyer Donny Van Zandt Gareth Ryder-Han- James Terry John Fiala Keith Zientek malifer Michael Rees Patrick Holloway Robert Andersson Selesias TiresiasBC ^JJ^ Anton Skovorodin Carlos de la Cruz Curtis D Carbonell Dorian rahan James Trimble John Forinash Kelly Brown Manfred Gabriel Michael Robins Patrick Martin Frosz Robert Biddle Selganor Yoster Todd 2002simon01 Antonio Miguel Morales CURTIS RICKER Doug Atkinson Garrett Rooney James Turnbull John GT Kelroy Was Here Manticore2050 Michael Ruff Nielsen Robert Biskin seraphim_72 Todd Agthe 2Die10 Games Martorell Ferriol Carlos Gustavo D. Cardillo Doug Keester Garry Jenkins James Winfield John H. Ken Manu Marron Michael Ryder Patrick McCann Robert Challenger Serge Beaumont Todd Blake 64 Oz. Games Aoren Flores Ríos D. Christopher Doug Kern Gary Buckland James Wood John Hartwell ken Bronson Manuel Pinta Michael Sauer Patrick Menard Robert Conley Sérgio Alves Todd Bogenrief 6mmWar Apocryphal Lore Carlos Ovalle Dawson Dougal Scott Gary Gin Jamie John Heerens Ken Bullock Guerrero Michael Scholl Patrick Mueller-Best Robert Daines Sergio Silvio Todd Cash 7th Dimension Games Aram Glick Carlos Rincon D. Daniel Wagner Douglas Andrew Gary Kacmarcik Jamie MacLaren John Hergenroeder Ken Ditto Manuel Siebert Michael Sean Manley Patrick Murphy Robert Dickerson Herrera Gea Todd Dyck 9thLevel Aram Zucker-Scharff caroline D.J. -

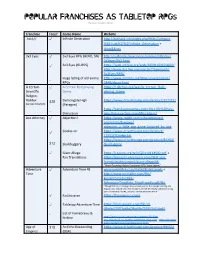

POPULAR FRANCHISES AS TABLETOP RPGS Revision 10 (Apr.2021)

POPULAR FRANCHISES AS TABLETOP RPGS Revision 10 (Apr.2021) Franchise Free? Game Name Website .hack// ✓ Infinite Generation http://dothack.info/index.php?title=Category %3A.hack%2F%2FInfinite_Generation + Odds&Ends 3x3 Eyes ✓ 3x3 Eyes RPG (HERO, SN) http://surbrook.devermore.com/worldbooks/ 3x3eyes/3x3.html ✓ 3x3 Eyes (GURPS) https://web.archive.org/web/20001109020600/ http://www.dca.fee.unicamp.br/~henriqmh/ 3x3Eyes/RPG/ Huge listing of old anime http://www.oocities.org/timessquare/arena/ - RPGs 2448/about.html A Certain ✓ A Certain Roleplaying https://1d4chan.org/wiki/A_Certain_Role- Scientific Game playing_Game Railgun, Raildex $20 Demongate High https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/127312/ See also Smallville. (Paragon) https://yarukizerogames.com/2011/02/10/role- - Discussion play-this-a-certain-scientific-railgun/ Ace Attorney ✓ Abjection! https://www.reddit.com/r/AceAttorney/ comments/8zwgwa/ abjection_a_little_rpg_game_inspired_by_ace ✓ Cookie Jar https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/ 115517/Cookie-Jar https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/84260/ $12 Skullduggery Skulduggery ✓ Giant Allege: https://i.4pcdn.org/tg/1520114144592.pdf + Fan Translations https://projects.inklesspen.com/fatal-and- friends/professorprof/giant-allege/#6 “Heart-Pounding Robot Courtroom RPG" from Japan!” Adventure ✓ Adventure Time 4E www.mediafire.com/?ia9628cdx6zacwb + Time http://www.mediafire.com/file/ kmxkml5mzduc994/ AdventureTimeBeta_PrintFriendly.pdf/file “Though I’m not releasing a new version just for this, people reading this original post should -

1540355802564.Pdf

OCTOBER 23rd 2018 Attention PDF authors and publishers: Da Archive runs on your tolerance. If you want your product removed from this list, just tell us and it will not be included. This is a compilation of pdf share threads since 2015 and the rpg generals threads. Some things are from even earlier, like Lotsastuff’s collection. Thanks Lotsastuff, your pdf was inspirational. And all the Awesome Pioneer Dudes who built the foundations. Many of their names are still in the Big Collections A THOUSAND THANK YOUS to the Anon Brigade, who do all the digging, loading, and posting. Especially those elite commandos, the Nametag Legionaires, who selflessly achieve the improbable. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – The New Big Dog on the Block is Da Curated Archive. It probably has what you are looking for, so you might want to look there first. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – Don't think of this as a library index, think of it as Portobello Road in London, filled with bookstores and little street market booths and you have to talk to each shopkeeper. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to ~16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. Some links are encoded without a hyperlink to restrict spiderbot activity. You will have to complete the link. Sorry for the inconvenience. Others are encoded but have a working hyperlink underneath. Some are Spoonerisms or even written backwards, Enjoy! ss, @SS or $$ is Send Spaace, m3g@ is Megaa, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. -

Popular Franchises As Tabletop Rpgs Rev. 6 (Nov. 2020)

Popular Franchises as Tabletop RPGs Rev. 6 (Nov. 2020) Ctrl+F to find your way around. Use capitalization if nothing is coming up. Franchise Free? Game Name Website .hack// ✓ Infinite Generation http://dothack.info/index.php?title=Category%3 A.hack%2F%2FInfinite_Generation A Certain ✓ A Certain Roleplaying https://1d4chan.org/wiki/A_Certain_Role- Scientific Game playing_Game Railgun Ace Attorney ✓ Abjection! https://www.reddit.com/r/AceAttorney/commen ts/8zwgwa/abjection_a_little_rpg_game_inspired _by_ace ✓ Cookie Jar https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/115517/ Cookie-Jar https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/84260/S $12 Skullduggery kulduggery Adventure ✓ Adventure Time 4E www.mediafire.com/?ia9628cdx6zacwb + Time http://www.mediafire.com/file/kmxkml5mzduc9 94/AdventureTimeBeta_PrintFriendly.pdf/file “Though I’m not releasing a new version just for this, people reading this original post should note that hit points should be initially calculated using your constitution SCORE, not your constitution MODIFIER.” FarUniverse https://faruniverse.com/ ✓ https://docs.google.com/file/d/0BwNr37N7Yp6b ✓ Tabletop Adventure Time cDRmMnZSZ0V3a2s/edit - List of homebrews & https://www.reddit.com/r/rpg/comments/81nf9g/any_chance_of_a n_english_adventure_time_rpg/ + https://mutant- history future.fandom.com/wiki/Adventure_Time Age of ✓ Gods and Monsters https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/150889/ Mythology (Fate) Akira $10 KISHU (PbtA) https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/319947/ See also Battle KISHU Angel: Alita. $11 Cybergeneration (CP2020) https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/25143/ ✓ Psychedemia (Fate) https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/142732/ Aladdin $50 City of Brass (5E) https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/266871/ Prince of City-of-Brass-5e Often goes on sale for significantly less. Persia, The $25 City of Brass (SW/OSR) https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/266876/ Etc. -

FEBRUARY 20Th 2018

February 20th We love you, Archivist! FEBRUARY 20th 2018 Attention PDF authors and publishers: Da Archive runs on your tolerance. If you want your product removed from this list, just tell us and it will not be included. This is a compilation of pdf share threads since 2015 and the rpg generals threads. Some things are from even earlier, like Lotsastuff’s collection. Thanks Lotsastuff, your pdf was inspirational. And all the Awesome Pioneer Dudes who built the foundations. Many of their names are still in the Big Collections A THOUSAND THANK YOUS to the Anon Brigade, who do all the digging, loading, and posting. Especially those elite commandos, the Nametag Legionaires, who selflessly achieve the improbable. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – The New Big Dog on the Block is Da Curated Archive. It probably has what you are looking for, so you might want to look there first. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – Don't think of this as a library index, think of it as Portobello Road in London, filled with bookstores and little street market booths and you have to talk to each shopkeeper. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to ~16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. Some links are encoded without a hyperlink to restrict spiderbot activity. You will have to complete the link. Sorry for the inconvenience. Others are encoded but have a working hyperlink underneath. Some are Spoonerisms or even written backwards, Enjoy! ss, @SS or $$ is Send Spaace, m3g@ is Megaa, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. -

Issue 4 D6 Magazine Issue 4

TABLE OF CONTENTS... Talking With Peter Schweighofer by Jeremy Streeter .......... page 02 Firearms by Phil Hatfield .......... page 09 “Doc-Woc” and the Angel by Ray McVay .......... page 16 Pulp Adventure by Phil Hatfield .......... page 18 Rethinking The Wild Die by Michael Fraley .......... page 21 Cover Art Illustrated by Rich Woodall Edited by Brett M. Pisinski As the d6 Magazine heads in a new direction, we will continue to grow and expand with each issue. Like everything, we’re not immune to the effects of growing pains, it will be a process for everyone involved, but these are exciting times for d6 gaming! I would like to thank the online d6 community in their efforts for helping spread the word and involvement. The d6 System itself has gone through many changes since its initial conception in the late ‘70s, to the height of its popularity when West End Games held the Star Wars license to the OpenD6 OGL that we have now. The future of d6 gaming is looking very bright, with all the talented minds we have now. I am looking forward to working with everyone as we begin to push the boundaries of our imaginations while we continue to challenge ourselves. Never stop dreaming, anything is possible. Roll for initiative! Respectfully, - Brett M. Pisinski OpenD6 OGL 2.0 and Wicked North Games, LLC. Copyright April of 2012 Talking with Peter Schweighofer by Jeremy Streeter oversee the editorial staff, worked conventions, authored or contributed material to a number of games and sourcebooks -- including the Star Wars Roleplaying Game, 2nd Edition Revised & Expanded, Platt’s Starport Guide, the Raiders of the Lost Ark Sourcebook, Instant Adventures -- and generally contributed opinions and guidance on numerous game projects West End developed. -

Solo Roleplayer: the Collected Archives

Solo Roleplayer The Collected Archives Kenny Norris Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Important Notes ..................................................................................................................................................................................2 Solo RPG Resources and Tools............................................................................................................................................................ 3 The Top 5 Essential Tools for Solo RPG Tools....................................................................................................................................5 PhraseExpander: Speeding Up Play and Life .................................................................................................................................. 14 3 Elements of a Great Solo RPG Adventure...................................................................................................................................... 16 How to Respark Your Missing Roleplaying Passion ....................................................................................................................... 18 How to Respark your Missing Roleplaying Passion: An Example ................................................................................................. 21 4 Simple Steps to Start Solo Roleplaying ........................................................................................................................................ -

Tg/ Roleplaying Games Census 2017 Which Roleplaying System/Systems Have You Used the Most in 2017? Votes Percentage 442 D&D

/tg/ Roleplaying Games Census 2017 Which roleplaying system/systems have you used the most in 2017? Votes Percentage 442 D&D 5e 166 37.60% Pathfinder 25 5.70% Warhammer 40,000 Roleplay 20 4.50% Shadowrun 19 4.30% World Of Darkness 17 3.80% D&D 3.5 15 3.40% Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay 15 3.40% Star Wars Roleplaying Game 12 2.70% D&D Other 10 2.30% Savage Worlds 10 2.30% GURPS 9 2% Homebrew System 7 1.60% FATE 6 1.40% 13th Age 5 1.10% Dungeon World 5 1.10% Call Of Cthulhu 5 1.10% Starfinder 4 0.90% Dungeon Crawl Classics 4 0.90% D&D 4e 4 0.90% Don’t play TTRPGs 4 0.90% Exalted 3 0.70% Stars Without Number 3 0.70% Legend Of The Five Rings 3 0.70% Traveller 3 0.70% Mythras/RuneQuest 2 0.50% Eclipse Phase 2 0.50% Mario RPG 2 0.50% Numenera 2 0.50% Strike! 2 0.50% Degenesis 2 0.50% Dread 2 0.50% Apocalypse World 2 0.50% Risus 2 0.50% Deadlands 1 0.20% Legends of the Wulin 1 0.20% The Sprawl 1 0.20% Mutants and Masterminds 1 0.20% Unofficial Elder Scrolls RPG 1 0.20% Barbarians of Lemuria 1 0.20% BLAM! 1 0.20% Star Trek Adventures 1 0.20% Blade Of The Iron Throne 1 0.20% Within The Ring Of Fire 1 0.20% Qin: The Warring States 1 0.20% Age Of Rebellion 1 0.20% One Roll Engine 1 0.20% Unknown Armies 1 0.20% Mouse Guard 1 0.20% Goblin Laws of Gaming 1 0.20% Into The Odd 1 0.20% Blades In The Dark 1 0.20% Marvel Superheroes 1 0.20% The Riddle Of Steel 1 0.20% Genesys 1 0.20% Cyberpunk 2020 1 0.20% Misfortune 1 0.20% Artesia: Adventures in the Known World 1 0.20% Symbaroum 1 0.20% Anima 1 0.20% The Dark Eye 1 0.20% Nechronica 1 0.20% Splittermond 1 -

Timeline Tree of Tabletop Role-Playing Games Pascal Martinolli

Timeline Tree of Tabletop Role-Playing Games Pascal Martinolli To cite this version: Pascal Martinolli. Timeline Tree of Tabletop Role-Playing Games. Donjons & Données probantes, Nov 2018, Montréal, Canada. 2019. halshs-02522264 HAL Id: halshs-02522264 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02522264 Submitted on 1 Apr 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial| 4.0 International License TTTTRPG - Timeline Tree of Tabletop Role-Playing Games, Celebrating more than 40 years of innovations in game designs Free Kriegsspiel movement Referee renders decisions Midwest Military Simulation Association past Strategos: A Series of American Games of War (...) [Totten CAL, 1890] 1960 on tactical experience only (not on rules) (1963) Pascal Martinolli (CC-BY-NC-SA) 2016-2019 [1860-1880] github.com/pmartinolli/TTTTRPG v.20200118 Diplomacy [Allan B. Calhamer, 1954-59] 1950 PC centered game-play fostering emergent roleplay Modern War in Miniature 1966 [Michael F Korns, 1966] Braunstein 1967 [David A Wesely, 1967] Hyboria [Tony Bath, 1968-1973?] PC centered play-by-post wargame 1968 Random personality creation Fantasy world building campaign. Long-lasting consequences of PC decisions on the game-world 1969 The Courrier [of NEWA] Strategos ’N’ two-pages set of rules 1970 One figure = One character Simulation & Gaming WARriors vs GAMErs (Perren S) Castle & Crusade Society Lake Geneva Tactical Studies Association [David A. -

Explosive Runes 25 .COM Contents

ISSUE 25 WINTER 2018 THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF WWW.RPGCROSSING.COM EXPLOSIVE RUNES 25 WWW.RPGCROSSING .COM CONTENTS 3. LETTER FROM THE EDITOR Short Story News SIGHT OF SPRING 29. 4. RUMOURS IN THE TAVERN Game Tools Feature THE TROUBLE WITH 3D COMBAT 32. 7. PIMP YOUR GAME! Adventure Short Story DARK ENCOUNTER ON FLEXIAR ISLAND 34. 15. WHO DO YOU TRUST? Short Story Adventure TANGLED 41. 21. THE CHILD EMPEROR Game Tools SPICE UP YOUR GAME 45. 2 EXPLOSIVE RUNES 25 WWW.RPGCROSSING .COM Letter from The Editor hank you for picking handle it. What about a short the northern hemisphere), up (virtually at story, or an article, or a helpful DEPENDING UPON YOU! We least) this issue of hint or tip or three on playing need your input, your ideas, Explosive Runes. RPG’s? We’d love to have it. We your contributions. You can DUNGEON TASK MASTER Once again, I would need YOUR participation, too, read the issue and enjoy it, and Dirkoth like to thank the hard working to make the next issue great! we are happy. But, if you get Tgnomes who helped with the inspired, and want to share, we DUNGEON CREW issue, including GodRosen, Of course, we’d love to have would be ecstatic! Explosive GodRosen, undeadrajib, Grogg undeadrajib, Grogg Tree, and your help on the newsletter Runes is built by community Tree, Ytterbium, and Inem. Inem. Without them, and staff as well. You can join us, ideas, inspired by our our other contributors, we behind the scenes, and be part community gamers, and created COVER ART wouldn’t have an issue. -

Risus: the Anything RPG (Version 2.01)

Welcome to Risus: The Anything RPG, a complete pen-and-pa- He probably owns at least one sturdy hand-weapon and per roleplaying game! For some, Risus is a handy “emergency” (hopefully, mercifully) a complete loincloth. If you’re playing a RPG for spur-of-the-moment one-shots and rapid character Psychic Schoolgirl (3), you probably have the power to sense creation. For others, it’s a reliable campaign system supporting (and be freaked-out by) the psychometric residue lingering years of play. For others still, it’s a strange little pamphlet with at a murder scene, and might own a cute plushy stick figures. For me, it’s all three, and with this edition, Risus backpack filled with school supplies. If you’re celebrates not only two decades of existence, but two playing a Roguish Space Pirate (3), you decades of life, bolstered by an enthusiastic global can do all kinds of piratey roguey community devoted to expanding it, celebrating it, space-things, and you probably sharing it, and gaming with it. own a raygun, and maybe a sec- ondhand star freighter. When there’s Character Creation any doubt about your character’s abilities or “Tools of the Trade,” discuss The character Cliché is the heart of Risus. Clichés are it with your GM. shorthand for a kind of person, implying their skills, Tools of the Trade come “free” as part background, social role and more. The “character of each Cliché, but they’re vulnerable classes” of the oldest RPGs are enduring Clichés: to loss or damage, which can (sometimes) Wizard, Detective, Starpilot, Superspy.