Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

Henrietta Van Der Blom, Christa Gray, and Catherine Steel (Eds.)

Henrietta Van der Blom, Christa Gray, and Catherine Steel (eds.). Institutions and Ideology in Republican Rome. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2017. Hb. $120.00 USD. Institutions and Ideology in Republican Rome is a collection of papers first presented at a conference in 2014, which in turn arose from the Fragments of the Republican Roman Orators (FRRO) project. Perhaps ironically, few of these papers focus on oratorical fragments, although the ways in which Republican politicians communicated with each other and the voting public is a common theme across the collection. In their introduction the editors foreground the interplay between political institutions and ideology as a key point of conflict in late Republican politics, taking aim in particular at the interpretation of Republican political life as dominated by money and self-serving politicians at the top and by institutionally curated consensus at the bottom. This, they argue, is unsustainable, not least in light of the evidence presented by their contributors of politicians sharing and acting on ‘ideological’ motives within the constraints of Republican institutions. Sixteen papers grouped into four sections follow; the quality is consistently high, and several chapters are outstanding. The four chapters of Part I address ‘Modes of Political Communication’. Alexander Yakobson opens with an exploration of the contio as an institution where the elite were regularly hauled in front of the populus and treated less than respectfully by junior politicians they would probably have considered beneath them. He argues that the paternalism of Roman public life was undercut by the fact that ‘the “parents” were constantly fighting in front of the children’ (32). -

Percorsi Bici Depliant

The bicycle represents an excel- lent alternative to mobility-based travel and sustainable tourism. The www.turismoroma.it Eternal City is still unique, even by some bicycle. There are a total of 240 km INFO 060608 of cycle paths in Rome, 110 km of useful info which are routed through green areas, while the remainder follow public roads. The paths follow the courses of the Tiber and Aniene rivers and along the line of the coast at Ostia. Bicycle rental: Bike sharing www.gobeebike.it www.o.bike/it Casa del Parco Vigna Cardinali Viale della Caffarella Access from Largo Tacchi Venturi for information and reservations, call +39 347 8424087 Appia Antica Service Centre Via Appia Antica 58/60 stampa: Gemmagraf Srl - copie 5.000 10/07/2018 For information and reservations, call +39 06 5135316 www.infopointappia.it Rome by bike communication Valley of the Caffarella The main path of the Valley of the Caffarella, scene of myths and legends intertwined with the history of Rome, features a wide range of biodiversity as well as important historical heritage, such as a part of the Triopius of Herod Atticus. Entering the park via the Via Latina entrance in correspondence with Largo Tacchi e Venturi, head right up to Via della Caffarella and follow the path to the Appia Antica, approxima- tely 6 km away. Along the way you'll encounter: the Casale della Vaccareccia, consisting of a medieval tower and a sixteenth century farmhouse, built by Caffarelli who, in the sixteenth century, reclaimed the area; the Sepolcro di Annia Regilla, a sepulchral monument shaped like a small temple, and the meandering Almone river, a small tributary of the Tiber, thought to be sacred by the ancient Romans. -

The Lex Sempronia Agraria: a Soldier's Stipendum

THE LEX SEMPRONIA AGRARIA: A SOLDIER’S STIPENDUM by Raymond Richard Hill A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University August 2016 © 2016 Raymond Richard Hill ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Raymond Richard Hill Thesis Title: The Lex Sempronia Agraria: A Soldier’s Stipendum Date of Final Oral Examination: 16 June 2016 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Raymond Richard Hill, and they evaluated his presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. Katherine V. Huntley, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Lisa McClain, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Lee Ann Turner, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by Katherine V. Huntley, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved for the Graduate College by Jodi Chilson, M.F.A., Coordinator of Theses and Dissertations. DEDICATION To Kessa for all of her love, patience, guidance and support. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to Dr. Katherine Huntley for her hours spent proofing my work, providing insights and making suggestions on research materials. To Dr. Charles Matson Odahl who started this journey with me and first fired my curiosity about the Gracchi. To the history professors of Boise State University who helped me become a better scholar. v ABSTRACT This thesis examines mid-second century BCE Roman society to determine the forces at work that resulted in the passing of a radical piece of legislation known as the lex Sempronia agraria. -

Pro Milone: the Purposes of Cicero’S Published Defense Of

PRO MILONE: THE PURPOSES OF CICERO’S PUBLISHED DEFENSE OF T. ANNIUS MILO by ROBERT CHRISTIAN RUTLEDGE (Under the Direction of James C. Anderson, Jr.) ABSTRACT This thesis explores the trial of T. Annius Milo for the murder of P. Clodius Pulcher, which occurred in Rome in 52 BC, and the events leading up to it, as well as Marcus Tullius Cicero’s defense of Milo and his later published version of that defense. The thesis examines the purposes for Cicero’s publication of the speech because Cicero failed to acquit his client, and yet still published his defense. Before specifically examining Cicero’s goals for his publication, this thesis considers relationships between the parties involved in the trial, as well as the conflicting accounts of the murder; it then observes the volatile events and novel procedure surrounding the trial; and it also surveys the unusual topographic setting of the trial. Finally, this thesis considers the differences between the published speech and the speech delivered at trial, the timing of its publication, and possible political and philosophical purposes. INDEX WORDS: Marcus Tullius Cicero, Pro Milone, Titus Annius Milo, Publius Clodius Pulcher, Pompey, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, Quintus Asconius Pedianus, Roman Courts, Roman Trials, Roman Criminal Procedure, Ancient Criminal Procedure, Roman Rhetoric, Latin Rhetoric, Ancient Rhetoric, Roman Speeches, Roman Defense Speeches, Roman Topography, Roman Forum, Roman Philosophy, Roman Stoicism, Roman Natural Law, Roman Politics PRO MILONE: THE PURPOSES OF CICERO’S PUBLISHED DEFENSE OF T. ANNIUS MILO by ROBERT CHRISTIAN RUTLEDGE B.A. Philosophy, Georgia State University, 1995 J.D., University of Georgia, 2005 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2006 © 2006 Robert Christian Rutledge All Rights Reserved PRO MILONE: THE PURPOSES OF CICERO’S PUBLISHED DEFENSE OF T. -

Ancient Roman Tour Walk with the Ancient Romans TOUR DIFFICULTY EAZY MEDIUM HARD

SHORE EXCURSION BROCHURE FROM THE PORT OF ROME DURATION 10 hr Ancient Roman Tour Walk With The Ancient Romans TOUR DIFFICULTY EAZY MEDIUM HARD our driver will pick you up at your cruise ship for an experience of a lifetime. YYour Own Italy’s Private Rome shore excursion of Ancient Rome includes the Colosseum, Appian Way, Pantheon, Ancient Rome Forum and much more. Ideal for families and those looking for an in-depth and thoroughly entertaining tour focusing on the life and times of Ancient Romans. First, with your private English-speaking guide, visit the alluring remains of the Ancient Roman Forum. While walking through the ruins of the imposing ancient buildings, you will lis- ten to its history -- peppered with anecdotes about the structure of Roman so- ciety, their beliefs, their social and political life. Learn how the Romans managed to create and control such a vast territory and how that empire declined. hen, avoiding the lines to get in to the Colosseum, you’ll visit the imposing Tarena and relive the days of Ancient Rome! Enjoy a thorough tour of the building, learning about the inner workings of the Colosseum and the special effects and showmanship of the ferocious games played there…the role the Col- osseum had in Roman society…and what it meant to a Roman to attend these games…what different games where held in the amphitheater. Afterwards, you will be taken on a short drive through the center of Rome to see the Pantheon, and learn about the rich history of one of Rome’s most important and beautiful buildings. -

Monuments and Memory: the Aedes Castoris in the Formation of Augustan Ideology

Classical Quarterly 59.1 167–186 (2009) Printed in Great Britain 167 doi:10.1017/S00098388090000135 MONUMENTSGEOFFREY AND MEMORY S. SUMI MONUMENTS AND MEMORY: THE AEDES CASTORIS IN THE FORMATION OF AUGUSTAN IDEOLOGY I. INTRODUCTION When Augustus came to power he made every effort to demonstrate his new regime’s continuity with the past, even claiming to have handed power in 28 and 27 B.C. back to the Senate and people of Rome (Mon. Anc. 34.1). He could not escape the reality, however, that his new monarchical form of government was incompatible with the political ideals of the Republic. At the same time, Augustus was attempting to reunite a society that in the recent past had been riven by civil conflict. It should be no surprise, then, that the new ideology that evolved around the figure of the princeps attempted to retain the memory of the old Republic while at the same time promoting and securing the power of a single authority through which Rome could flourish.1 The new regime’s relationship to the recent past was complicated, too, inasmuch as Augustus’ power was forged in the cauldron of the late Republic, and he was the ultimate beneficiary of the political upheaval of his youth. Augustus’ new ideology had to recall the Republic without lingering over its tumultuous last generation; it had to restore and renew.2 Augustus’ boast that he found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble as well as the long list in the Res Gestae (Mon. Anc. 19–21.2) of monuments that he either built or restored declare that the new topography of the city was an important component of this new ideology. -

Searching for Blood in the Streets: Mapping Political Violence Onto

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects Spring 5-2016 Searching for Blood in the Streets: Mapping Political Violence onto Urban Topography in the Late Roman Republic, 80-50 BCE Theodore Samuel Rube Bates College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Rube, Theodore Samuel, "Searching for Blood in the Streets: Mapping Political Violence onto Urban Topography in the Late Roman Republic, 80-50 BCE" (2016). Honors Theses. 186. http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/186 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Searching for Blood in the Streets: Mapping Political Violence onto Urban Topography in the Late Roman Republic, 80-50 BCE An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Classical and Medieval Studies Bates College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts By Theodore Samuel Rube Lewiston, Maine March 28th, 2016 2 Acknowledgements I want to take this opportunity to express my sincerest gratitude to everybody who during this process has helped me out, cheered me up, cheered me on, distracted me, bothered me, and has made the writing of this thesis eminently more enjoyable for their presence. I am extremely grateful for the guidance, mentoring, and humor of Professor Margaret Imber, who has helped me through every step of this adventure. I’d also like to give a very special thanks to the Bates Student Research Fund, which provided me the opportunity to study Rome’s topography in person. -

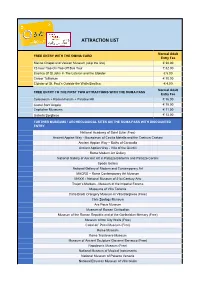

Attraction List

ATTRACTION LIST Normal Adult FREE ENTRY WITH THE OMNIA CARD Entry Fee Sistine Chapel and Vatican Museum (skip the line) € 30.00 72-hour Hop-On Hop-Off Bus Tour € 32.00 Basilica Of St.John In The Lateran and the Cloister € 5.00 Carcer Tullianum € 10.00 Cloister of St. Paul’s Outside the Walls Basilica € 4.00 Normal Adult FREE ENTRY TO THE FIRST TWO ATTRACTIONS WITH THE ROMA PASS Entry Fee Colosseum + Roman Forum + Palatine Hill € 16.00 Castel Sant’Angelo € 15.00 Capitoline Museums € 11.50 Galleria Borghese € 13.00 FURTHER MUSEUMS / ARCHEOLOGICAL SITES ON THE ROMA PASS WITH DISCOUNTED ENTRY National Academy of Saint Luke (Free) Ancient Appian Way - Mausoleum of Cecilia Metella and the Castrum Caetani Ancient Appian Way – Baths of Caracalla Ancient Appian Way - Villa of the Quintili Rome Modern Art Gallery National Gallery of Ancient Art in Palazzo Barberini and Palazzo Corsini Spada Gallery National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art MACRO – Rome Contemporary Art Museum MAXXI - National Museum of 21st Century Arts Trajan’s Markets - Museum of the Imperial Forums Museums of Villa Torlonia Carlo Bilotti Orangery Museum in Villa Borghese (Free) Civic Zoology Museum Ara Pacis Museum Museum of Roman Civilization Museum of the Roman Republic and of the Garibaldian Memory (Free) Museum of the City Walls (Free) Casal de’ Pazzi Museum (Free) Rome Museum Rome Trastevere Museum Museum of Ancient Sculpture Giovanni Barracco (Free) Napoleonic Museum (Free) National Museum of Musical Instruments National Museum of Palazzo Venezia National Etruscan -

Appius Claudius Caecus 'The Blind'

Appius Claudius Caecus ‘The Blind’ Faber est quisquis suae fortunae (‘Every man is architect of his own fortune’) Appius Claudius Caecus came from the Claudian gens, a prime patrician family that could trace its ancestors as far back as the decemvirs who authored Rome’s first laws (the Twelve Tables) in the mid-fifth century BC. Although many Roman families could boast successful ancestors, Appius Claudius Caecus has the distinction of being one the first characters in Roman history for whom a substantial array of material evidence survives: a road, an aqueduct, a temple and at least one inscription. His character and his nickname Caecus, ‘The Blind’, are also explained in historical sources. Livy (History of Rome 9.29) claims he was struck down by the gods for giving responsibilities of worship to temple servants, rather than the traditional family members, at the Temple of Hercules. Perhaps a more credible explanation is offered by Diodorus Siculus (20.36), who suggests that Appius Claudius said he was blind and stayed at home to avoid reprisals from the Senate after his time in office. In that case, his name was clearly coined in jest, as is often the case with cognomen. Appius Claudius Caecus, whether or not he was actually blind, is an illuminating case study in the ways that varying types of evidence (literature, inscriptions and archaeology) can be used together to recreate history. His succession of offices, not quite the typical progression of the cursus honorum, records a man who enjoyed the epitome of a successful career in Roman politics (Slide 1). -

Traditional Political Culture and the People's Role in the Roman Republic

TRADITIONAL POLITICAL CULTURE AND THE PEOPLEʼS ROLE IN THE ROMAN REPUBLIC The peopleʼs role in the political system of the Roman Republic has been at the centre of scholarly debate since Millarʼs challenge to the traditional oligarchic interpretation of Republican politics.1 Today, few would dismiss the signifi cance of the popular ele- ment in the system altogether. However, many scholars strongly insist that in the fi nal analysis, the Republic, whatever popular or pseudo-popular features it possessed, was a government of the elite, by the elite and for the elite. This has increasingly come to be attributed to the cultural hegemony of the Roman ruling class. Rather than excluding the common people from the political process, the elite, it is now argued, was able to make sure that the part they played in politics would be broadly positive from its point of view. What follows is a critical examination of this thesis. I. Cultural factors and the power of the elite The debate on Roman “democracy” is inevitably infl uenced by oneʼs understanding of this loaded term, which is often strongly informed by modern democratic theory and experience. That modern political systems usually regarded as democratic include a considerable element of elite control and manipulation is of course a truism.2 How far-reaching, and, indeed, “undemocratic” the infl uence of this elitist element is, and what room it leaves for genuine popular participation – these are debatable points, both analytically and ideologically. Hence there can be no full agreement as to what it is we are looking for when we inquire about “democratic” features in the Roman Republic. -

The Discovery and Exploration of the Jewish Catacomb of the Vigna Randanini in Rome Records, Research, and Excavations Through 1895

The Discovery and Exploration of the Jewish Catacomb of the Vigna Randanini in Rome Records, Research, and Excavations through 1895 Jessica Dello Russo “Il cimitero di Vigna Randanini e’ il punto di partenza per tutto lo studio della civilta’ ebraica.” Felice Barnabei (1896) At the meeting of the Papal Commission for Sacred Archae- single most valuable source for epitaphs and small finds from ology (CDAS) on July 21,1859, Giovanni Battista de Rossi the site.6 But the catacomb itself contained nothing that was of strong opinion that a newly discovered catacomb in required clerical oversight instead of that routinely performed Rome not be placed under the Commission’s care.1 Equally by de Rossi’s antiquarian colleagues at the Papal Court. surprising was the reason. The “Founder of Christian Archae- On de Rossi’s recommendation, the CDAS did not assume ology” was, in fact, quite sure that the catacomb had control over the “Jewish” site.7 Its declaration, “la cata- belonged to Rome’s ancient Jews. His conclusions were comba non e’ di nostra pertinenza,” became CDAS policy drawn from the very earliest stages of the excavation, within for the next fifty years, even as three other Jewish cata- sight of the catacombs he himself was researching on the combs came to light in various parts of Rome’s suburbium.8 Appian Way southeast of Rome. They would nonetheless In each case, the discovery was accidental and the excava- determine much of the final outcome of the dig. tion privately conducted: the sites themselves were all even- The CDAS had been established just a few years before in tually abandoned or destroyed.