ABSTRACT an INTERNSHIP with the NATURE CONSERVANCY's NORTHERN CARIBBEAN PROGRAM by Sharrah Moss in Fulfillment of the Master

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment of the Effects and Impacts of Hurricane Matthew the Bahamas

AssessmentThe Bahamas of the Effects and Impacts of Hurricane Matthew The Bahamas Oct 6, - 7:00 pm 1 2 3 4 6 7 Centre path of Hurricane Matthew 1 Grand Bahama 2 Abaco 8 5 3 Bimini Islands 4 Berry Islands 12 5 Andros Hurricane force winds (74+ mph) 6 New Providence 9 7 11 Eleuthera 50+ knot winds (58+ mph) 8 Cat Island 9 The Exumas 10 Tropical storm force winds (39+mph) 10 Long Island 11 Rum Cay 14 12 San Salvador 13 Ragged Island 14 Crooked Island 15 Acklins 16 Mayaguna 13 15 16 17 The Inaguas 17 Oct 5, - 1:00 am 1 Hurricane Matthew 2 The Bahamas Assessment of the Effects and Impacts of Hurricane Matthew The Bahamas 3 Hurricane Matthew Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean Omar Bello Mission Coordinator, Affected Population & Fisheries Robert Williams Technical Coordinator, Power & Telecommunications Michael Hendrickson Macroeconomics Food and Agriculture Organization Roberto De Andrade Fisheries Pan American Health Organization Gustavo Mery Health Sector Specialists Andrés Bazo Housing & Water and Sanitation Jeff De Quattro Environment Francisco Ibarra Tourism, Fisheries Blaine Marcano Education Salvador Marconi National Accounts Esteban Ruiz Roads, Ports and Air Inter-American Development Bank Florencia Attademo-Hirt Country Representative Michael Nelson Chief of Operations Marie Edwige Baron Operations Editorial Production Jim De Quattro Editor 4 The Bahamas Contents Contents 5 List of tables 10 List of figures 11 List of acronyms 13 Executive summary 15 Introduction 19 Affected population 21 Housing 21 Health 22 Education 22 Roads, airports, and ports 23 Telecommunications 23 Power 24 Water and sanitation 24 Tourism 24 Fisheries 25 Environment 26 Economics 26 Methodological approach 27 Description of the event 29 Affected population 35 Introduction 35 1. -

Terms of Reference Monitoring and Conservation Consultant

Terms of Reference Monitoring and Conservation Consultant I. ASSIGNMENT INFORMATION Project Title: Meeting the Challenge of 2020 in The Bahamas Post Title: Species Monitoring and Conservation Consultant Duration of Consultancy: 200 days II. BACKGROUND The Bahamas is a country of over 700 islands and cays. Its topographical construct of limestone has developed a distinct environment for The Bahamas comprised of numerous irreplaceable habitats and species, including vast expanses of Caribbean pine forest, tidal flats with thriving bonefish populations, extensive barrier reefs, the highest concentration of blue holes in the Western Hemisphere, and critical fish nursery habitat believed to contribute significantly to fisheries stocks throughout the Caribbean region. Even prior to The Bahamas becoming signatory to the Convention on Biological Diversity in 1993, The Bahamas has been involved with the conservation and preservation of nature. The Bahamas established the world’s first land and sea park in 1958 with the Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park. That initiative was further enhanced when the Government of The Bahamas doubled the existing protected area network in 2002, and in 2008 committed to protecting 20% of the country’s nearshore and marine habitat by 2020 as part of the Caribbean Challenge Initiative (CCI). The CCI was accomplished as of May 2019, and currently The Bahamas has a Protected Areas Network of more than fourteen (14) million acres. With that in mind, ‘Meeting the Challenge of 2020 in The Bahamas’ seeks to strengthen and integrate Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) management into broader landscape planning in efforts to reduce pressures on ecosystem services and biodiversity from competing resource uses. -

Marine Protected Areas Management Guidance Document

Bahamas Protected Photo by Shane Gross Marine Protected Area Management Guidance Document A Guide for Policy-Makers & Protected Area Managers SEATHEFUTURE September 2018 Prepared by the Bahamas National Trust Marine Protected Area Management Guidance Document | September 2018 A Companion Document to the Marine Protection Plan for expanding The Bahamas Marine Protected Areas Network to meet The Bahamas 2020 declaration (September 2018) Prepared by Global Parks & the Bahamas National Trust with support from The Nature Conservancy Bahamas Protected is a three-year initiative to effectively manage and expand the Bahamian marine protected areas (MPA) network. It aims to support the Government of The Bahamas in meeting its commitment to the Caribbean Challenge Initiative (CCI); a regional agenda where 11 Caribbean countries have committed to protect 20 percent of their marine and coastal habitat by 2020. CCI countries have also pledged to provide sustainable financing for effective management of MPAs. Bahamas Protected is a joint effort between The Nature Conservancy, the Bahamas National Trust, the Bahamas Reef Environment Educational Foundation and multiple national stakeholders, with major funding support from Oceans 5. For further information, please contact: Bahamas National Trust, P.O. Box N-4105, Nassau, N.P., The Bahamas. Phone: (242) 393-1317, Fax: (242) 393-4878, Email: [email protected] 1 Marine Protected Area Management Guidance Document | September 2018 Contents I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... -

Bahamas Proposed Protected Areas 2014

ANNEX I 40th Anniversary of The Bahamas proposal for The Expansion of The Protected Area System Of The Commonwealth of The Bahamas Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 3 A Unique Opportunity for MPA Declaration ............................................................................. 6 ABACO .............................................................................................................................................. 10 The Abaco Marls National Reserve ................................................................................................... 10 East Abaco Creeks National Park ...................................................................................................... 11 Cross Harbour Conservation Area ..................................................................................................... 12 South Abaco Blue Holes Conservation Area ...................................................................................... 13 ACKLINS/ CROOKED ISLAND ............................................................................................. 14 Acklin's Bight ..................................................................................................................................... 14 ANDROS ............................................................................................................................... 15 Andros Green Cay National Park ...................................................................................................... -

The Bahamas Experience

Case Study Marine Protected Areas Assigning IUCN Protected Area Management Categories – The Bahamas Experience “The process of assigning management categories to our national parks will help facilitate the planning of protected areas and protected area systems managed by BNT and other agencies, improve information management about protected areas and assist to regulate activities within protected areas.” Eric Carey, Executive Director, Bahamas National Trust1 Participants at the BIOPAMA-facilitated workshops Summary Credit: Lynn Gape, BNT At its first meeting, the Commonwealth Blue Charter has produced detailed guidance on the categories but Marine Protected Area (MPA) Action Group identified there are few documented examples of the assignment training on the International Union for Conservation of process. Nature (IUCN) protected area management categories As part of the process to improve the management as one of its capacity development needs. Each and expansion of The Bahamas MPA network, the protected area should be assigned to one of these Bahamas National Trust (BNT), with the Department categories, and governments should provide information of Marine Resources (DMR) and the Clifton Heritage on categories when submitting data on protected Authority, undertook a process to assign IUCN areas to the World Database of Protected Areas. IUCN protected area management categories to all sites under its purview, through a series of workshops in 2014. 1 https://www.biopama.org/news/bahamas-moves-to-assign- protected-areas-management-categories52 Protected areas of The Bahamas (as of 2015) Credit: Lindy Knowles, BNT Recommendations for categories for all designated Assigning categories can be difficult if there are multiple protected areas, including MPAs, were made. -

08Annualreportbnt Web.Indd

2008 Annual Report The Bahamas National Trust Tel: 242-393-1317 Fax: 242-393-4978 P.O. Box N-4105, Nassau, Bahamas [email protected] • www.bnt.bs President’s Message I am pleased to report that over the past four years as your president, The Bahamas National Trust has made tremendous strides. We have improved the infrastructure and management of our park system, forged meaningful partnerships, strengthened our leadership, and introduced thousands of visitors and Bahamians to the beauty and diversity of our country, while increasing awareness of the need to protect our precious resources. Our key objective of developing an integrated national park and pro- tected area system was achieved. I am particularly proud that we were able to improve public access and infrastructure at national parks on New Providence, Andros and Grand Bahama. Harrold and Wilson Ponds National Park on New Providence has become a world-class outdoor recreation and ecotourism venue for residents and visitors. The two boardwalks and viewing stations built in 2007/8 have facilitated visitor education and appreciation of this signifi- cant wetland and birding habitat. At the Abaco National Park and the Blue Hole National Park in Fresh Creek, Andros (with its new boardwalk and observation deck), wardens were hired for the first time. Park wardens employed by the BNT have increased from five in 2006 to 10 in 2008. Grand Bahama, home to three national parks, received significant attention in both 2007 and 2008. Working with the BNTs rejuvenated Grand Bahama Committee; the bridge at the Lucayan National Park was rebuilt. -

Treasures in the Sea

Generous support for this project comes from Lynette and Richard Jaffe, The Tiffany & Co. Foundation, the National Science Foundation (Grant No. OCE-0119976), Colina Imperial Insurance Ltd., and the Bahamas Reef Environment Educational Foundation. Managing Editor Meg Domroese Writers and Editors Meg Domroese, Christine Engels, Monique Sweeting, Lynn Gape Design and Illustration James Lui Science Education Advisors Ronique Curry, Garvin Tynes Primary School Barbara Dorsett,Thelma Gibson School Sheriece Lightbourne-Edwards, St. Cecilia’s Catholic Primary School Joan Knowles, Carlton Francis Primary School Dorothy M. Rolle, Ridgeland Primary School Portia Sweeting, Primary Science Education Coordinator, Ministry of Education,Youth,Sports and Culture Beverly J.T.Taylor, Assistant Director of Education, Ministry of Education,Youth,Sports and Culture Project Partners Bahamas National Trust Center for Biodiversity and Conservation Ministry of Education,Youth,Sports The Retreat,Village Road American Museum of Natural History and Culture P.O. Box N-4105 Central Park West at 79th Street Thompson Boulevard Nassau,The Bahamas New York,NY 10024 USA P.O. Box N-3913 242-393-1317 212-769-5742 Nassau,The Bahamas 242-393-4978 (fax) 212-769-5292 (fax) 242-322-8140 www.thebahamasnationaltrust.org cbc.amnh.org 242-323-8491 (fax) [email protected] [email protected] Copyright © 2007 Bahamas National Trust and American Museum of Natural History. Information in this publication may be reproduced for non-commercial, educational purposes, providing credit is given to the original work. For any other purposes, prior permission is required. ISBN 978-0-913424-59-9 Listing of publications or other resources does not imply endorsement by the Bahamas National Trust, the American Museum of Natural History, or the Ministry of Education,Youth,Sports and Culture. -

National Parks • Preserving Our Future

Managing National Parks • Preserving Our Future Cost of Managing National Parks Presenter: Catherine Pinder Director of Finance and Operations, Bahamas National Trust Overview! • Issues faced by our Nation and the role of the Bahamas National Trust • Resource protection cost and challenges • BNT sustainable funding mechanisms • The funding gap Issues faced by our nation and the role of the Bahamas National Trust • Competition for government funds – high crime, high unemployment, high health care costs, educational concerns • The Exuma Land and Sea Park formed in 1958 • The Bahamas National Trust formed in 1959 ➢ Bahamas National Trust ACT ➢ Charged with creating and managing the national parks ➢ Advisor to the government THE GAP Our cost verification report commissioned by the IDB in September 2016 and updated by The BNT in March 2018, shows funding needs for optimal performance as follows: Staffing Annual Investment Description Needs Operating Costs Needs Existing parks 211 $10,526,820 27,662,899 New and park expansions 18 1,370,672 3,711,200 Total at optimal performance 229 11,897,492 31,374,099 Historical operating budgets 60 $4,300,000 OPERATIONAL GAP 169 $7,597,492 BENEFITS OF AN OPTIMAL NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM: increased ecological assessments to identify and advocate for the increase in staff and designation of areas that should be protected; increased evaluations Science Resource protection larger travel budget to determine the effectiveness of our programs and expanded habitat restoration program increase in staff, increased enforcement, -

The Bahamas Protected Area Network Management Effectiveness Evaluation Workshop Report

The Bahamas Protected Area Network Management Effectiveness Evaluation Workshop July 22 – 24, 2014 Paradise Island, Bahamas Report submitted by: Table of Contents I. Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................1 II. Background ................................................................................................................................4 III. Conceptual Approach ...............................................................................................................5 IV. Workshop Implementation......................................................................................................6 V. Comparative Analysis (2009 – 2014).........................................................................................9 Protected Area Context.............................................................................................................9 Ecological and Socioeconomic Importance ................................................................................9 Vulnerability .............................................................................................................................12 Landscape/Seascape Planning and Protected Area Benefits ...................................................16 Pressures and Threats ..............................................................................................................18 Protected Area Planning, Inputs, Processes and Outputs ......................................................29 -

Marine Protected Areas Proposal

Bahamas Protected Marine Protection Plan for expanding The Bahamas Marine Protected Areas Network to meet The Bahamas 2020 declaration SEATHEFUTURE September 2018 20 by 20 White Paper Prepared by The Bahamas National Trust 20 by 20 White Paper : Marine Protection Plan | 1 A Proposal Prepared for the Office of the Prime Minister, Ministry of Environment and Housing and the Ministry of Agriculture and Marine Resources Prepared by the Bahamas Protected 20 by 20 White Paper Working Team: Lakeshia Anderson1, Craig Dahlgren2, Lindy Knowles1, Lashanti Jupp1, Shelley Cant-Woodside1, Shenique Albury-Smith3, Casuarina McKinney-Lambert4, Agnessa Lundy1 Bahamas National Trust1 Perry Institute for Marine Science2 The Nature Conservancy3 Bahamas Reef Environment Educational Foundation4 20 by 20 White Paper : Marine Protection Plan | 2 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................ 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................................................................... 13 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 14 THE BAHAMAS: A LEADER IN MARINE CONSERVATION ..................................................................... 15 BAHAMAS PROTECTED PROJECT ......................................................................................................... 16 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ............................................................................................................. -

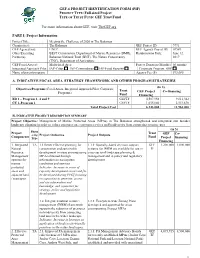

Financing Plan (In Us$)

GEF-6 PROJECT IDENTIFICATION FORM (PIF) PROJECT TYPE: Full-sized Project TYPE OF TRUST FUND: GEF Trust Fund For more information about GEF, visit TheGEF.org PART I: Project Information Project Title: Meeting the Challenge of 2020 in The Bahamas Country(ies): The Bahamas GEF Project ID: 9791 GEF Agency(ies): UNEP GEF Agency Project ID: 01569 Other Executing BEST Commission, Department of Marine Resources (DMR), Resubmission Date: June 12, Partner(s): Bahamas National Trust (BNT), The Nature Conservancy 2017 (TNC), Department of Agriculture GEF Focal Area(s): Multi-focal Area Project Duration (Months) 60 months Integrated Approach Pilot IAP-Cities IAP-Commodities IAP-Food Security Corporate Program: SGP Name of parent program: Agency Fee ($) 593,085 A. INDICATIVE FOCAL AREA STRATEGY FRAMEWORK AND OTHER PROGRAM STRATEGIES (in $) Objectives/Programs (Focal Areas, Integrated Approach Pilot, Corporate Trust Programs) GEF Project Co-financing Fund Financing BD 1 – Program 1, 4 and 9 GEFTF 4,587,958 9,811,322 CC 1-Program 1 GEFTF 1,655,046 2,151,678 Total Project Cost 6,243,004 11,963,000 B. INDICATIVE PROJECT DESCRIPTION SUMMARY Project Objective: Management of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in The Bahamas strengthened and integrated into broader landscape planning in order to reduce pressures on ecosystem services and biodiversity from competing resource uses (in $) Project Finan Trust -cing Project Outcomes Project Outputs GEF Co- Components Type Fund Project financing Financing 1. Integrated TA 1.1 Better effective planning for 1.1.1: Spatially-based -

Island Full Name Phone Contacts Town/Settlement/Area

Commit. (1 to Assets available to assist with (e.g. Island Full Name Phone contacts Town/Settlement/Area Stranding Kit (B=big, S=small) 5, 1 is low) car/truck, boat, heavy equipment, etc.) ABACO BMMRO 366 4155 / 357 6666 / 577 0655 Sandy Point B + S 5 ABACO FRIENDS OF THE ENVIRONMENT 367 2721 Marsh Harbour 5 ABACO Carol Laing ? Guana / Treasure Cay ABACO David Knowles (BNT) 577 3134 / 367 2256 Marsh Harbour S ABACO Dr Derrick Bailey 393 1681 / 577 0397 Marsh Harbour is a vet ABACO George Phillpot ? Man-O-War ABACO Ishman Williams ? Moore's Island ABACO Israel Williams ? Crossing Rocks ABACO Jeremy Saunders (Fisheries) 366 4445 (hm) / 475 2005 (cell) Marsh Harbour ABACO Junior Albury 366 3058 / 475 1892 Casaurina / Cherokee / Bahama Palm Shores ABACO Leon Pinder ? Coopers Town ABACO Mark Gonsalves 577 0148 / 475 8756 / VHF 09 Watercolours Hope Town / Lubbers tools ABACO Michael Wheeler ? Crossing Rocks ABACO Patrick Roberts ? Sandy Point ABACO Paul Pinder ? Sandy Point ABACO Richard Sawyer ? Green Turtle Cay ABACO Rob Meister 424 5833 / 393 7909 / 363 7159 / 457 2065 Guana / Treasure Cay equipment ABACO Chamara Parotti 242-458-8300/[email protected] Spring City 5 Car ABACO Wayne Cornish (Fisheries) 367 3482 Marsh Harbour S ANDROS Glen Gaitor (Fisheries) 329 1110 / 471 8191 B; at the same location as below ANDROS Filmore Russell (Fisheries) 324 4088 S; at the same loation as above ANDROS Administrator Francita Neely 369 4569 South Andros ANDROS Administrators Office 329 2278 North & South Andros ANDROS Alyson Canestrari (AUTEC) 368