Women and Leadership in Sports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Athletics Rules to Athletics (Women) February 2018 Those of Men’S

General and Discipline Rules United Nations Inter-Agency Games Secretariat Change Log Date This Change# Document Was Type of Change Description Date Approved Comments Modified Amended rules #1, Approved by the Aligned women’s 18 28 February 2018 Rule amendment #4, and #7 for CC by email on 16 athletics rules to Athletics (Women) February 2018 those of men’s. It is not possible to Amended rule #5 have a tie situation 17 29 January 2018 Rule amendment for women’s table N/A in women’s table tennis tennis. Approved by the Amended several 16 7 December 2017 Rule amendment CC in Vienna on 3 darts rules May 2017 Amended several Approved by the 15 7 December 2017 Rule amendment beach volleyball CC in Vienna on 3 rules May 2017 Confirmed badminton rules #5, Approved by the amended rules #6 14 7 December 2017 Rule amendment CC in Vienna on 3 and #7; May 2017 renumbered subsequent rules Could be provisional pending Amended rule #5 Approved by the 13 7 April 2017 Rule amendment a review by for badminton CC in March 2017 captains and the CC in Vienna Approved by the Swimming (Men & Amended individual 12 14 March 2017 CC in Salou on 29 Women) medley order April 2015 Approved by the Added rules for 11 28 February 2017 Rule addition CC by email in Pool-Billiards February 2017 Cricket has been at the Games since Added rules for 2014, but for some 10 19 January 2017 Rule addition N/A Cricket reason was not added to this document Amended tennis Approved by CC by rules as requested 9 4 October 2016 Rule amendment email in October by captains at the Malaga -

SM-Liiga Saatiin Päätökseen Tulevaisuudesta

SM-liiga saatiin päätökseen Tulevaisuudesta retkieväin ei ole eikä sitä hallituksen nykyi- lutuksia ja muita häiriötekijöitä. Helpottaa sellä kokoonpanolla saada ikinä aikaan. Ei kaikkien kisaan osallistuvien päivää. hallituksen itse sitä ajatushautomoa tarvitse käydä läpi, vaan hoitaa sekin puoli omista Kilpailuiden pituus velvollisuuksistaan liitoa kohtaan. Kisapäivät alkavat olla liian pitkiä niin pe- Siksi syksyn kokouksessa on ensiarvoi- laajien kuin kisajärjestäjien kannalta. 12- sen tärkeää, että mukaan tulisi joku, jol- 14 tuntia on työ- tai kisapäivän pituudeksi la on aikaa ottaa tämä sarka hoitaakseen. aivan liikaa huonoilla yöunilla. Pelipäiväs- Oma näkemykseni on että hän ei saa olla sä saisi olla vain yksi pääsarja ja mahdolli- puheenjohtaja, koska olemme vahvasti pj- set B- sekä ikäkausisarjat. vetoinen liitto käytännön tasolla. Valitta- Jos kisamaksu on 35 euroa sisältäen pää- va puheenjohtaja joutuu tekemään paljon sarjan ja B-kisan, joka olisi 1. ja 2. kierrok- rutiiniasioita eikä silloin ole aikaa kehitel- sen pudonneille, niin yhdessä ennakkoil- lä uusia kuvioita. moittautumisen ja kisan aikataulutuksen Tietynlainen kylähullu ja Pelle Peloton kanssa koko kisapaketista saadaan paketti, tarvitaan hallituksen jäsenen asemassa rik- joka toimisi omaan tahtiinsa eikä rasittaisi Risto Spora komaan tuttuja latuja. Annetaan hänelle pelaajia eikä toimitsijoita. valtuudet miettiä uutta tapaa lähestyä tä- Ja kun meillä on käytössä ennakkoil- tä yksinkertaista lajia monikulmasta jopa moittautuminen, niin 1. kierroksen pudon- kierteellä nurkan takaa. nut näkee kaaviosta mihin kohtaa pääkisan Viime lehden jälkeen olin jo Huolestuttavaa on, ettei puheenjohta- po. ottelun hävinnyt menee ja tietää näin ajatellut että tämä nyt käsissä- juudesta ole käyty minkäänlaista keskuste- heti koska pelaa ”Looser Cupin” ottelunsa. si oleva lehti on viimeinen jon- lua viime vuosina. -

South African Darts Board of Control

SOUTH AFRICAN DARTS BOARD OF CONTROL SSTB. I H I (WUJATtD TO WOlUD OMTS FEOEMTMN) President: Secretary: S. David M. F. Johnson 3 Khan Lane P. O. Box 6282 ISIPINGO RAIL ROGGfiBAAI 8012 4110 Tel:. Cape Town 71-0954 ALL COMMUNICATIONS TO K 26 June 1979 AOOAESSED TO THE SECRETAAY Mr. Tom Fleetwood S e c r e t a r y American Darts Or>ganlsatlon 13641 Eastbrook Avenue B e l l f l o w e r California 90706 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Dear Mr. Fleetwood, INVITATION TO PARTICIPATE IN WORLD CUP II We acknowledge ana thank you for the invitation extended to oui Board, as the representatives of South Africa, to participate in the World Darts Federation's 1979 WORLD CUP II, to be hosted by your Organisation in Las Vegas on November 2-3, 1979. We confirm sending the following cable to-day: " SADBOC not playing World Cup II stop Letter follows stop Kind regards J o h n s o n SADBOC Secretary. " Participation in International sporting events by teams'and individuals representing South Africa receives considerable local and international attention'. The single cause for this special focus is the oppressive and humiliating practice of racial discrimination in South African sport a direct result of the racist policies of the South African authorities which reaches very deeply into every aspect of life in this country* It is the very firm standpoint of our Board that racial discrimination in sport obstructs its normal development and that it denies a rightful and fair opportunity for each and every sportsman and woman to develop their sportlng^talents and fo^ teams and'individuals to be .jSelected on merit and ability only to represent South Africa in world sp^rt. -

International Sports Federations Social Media Ranking #Ifranking Social Media from Side Stage to Main Stage

2020 INTERNATIONAL SPORTS FEDERATIONS SOCIAL MEDIA RANKING #IFRANKING SOCIAL MEDIA FROM SIDE STAGE TO MAIN STAGE Burson Cohn & Wolfe Sports (BCW Sports) is pleased to publish the 2020 International Sports Federations Social Media Ranking. Published for the fourth year in a row, this ranking aims to capture the social media footprint of international sports federations and provide insightful takeaways of how different content leads to different outcomes. 2020 has been a year unlike any other for sports federations. Despite setback after setback, with cancellations and postponements of sporting events around the world, the year has been revolutionary for the whole sports industry. Since matches and tournaments were not taking place, sports fans had to look for other channels of engagement. They found what they were looking for on social media. This year’s ranking, as per previous years, includes international sports federations (IFs) from both the Winter and Summer Olympic programmes. In addition, for the first time, non-Olympic IFs have also been included. This should serve to increase the comparative and informative value of the IF Ranking. On behalf of BCW Sports, I truly hope that you enjoy our findings. Share your thoughts by engaging with us at @bcwsport and use our hashtag #IFranking. Switzerland, January 2021 Lars Haue-Pedersen Managing Director BCW Sports 1 CONTENTS Will Non-Olympic be the Ones to Beat? 3 Performance Indicators 4 The Overall Ranking 5 Most Followed International Sports Federation on Social Media – Olympic IFs 5 -

Sportonsocial 2018 1 INTRODUCTION

#SportOnSocial 2018 1 INTRODUCTION 2 RANKINGS TABLE 3 HEADLINES 4 CHANNEL SUMMARIES A) FACEBOOK CONTENTS B) INSTAGRAM C) TWITTER D) YOUTUBE 5 METHODOLOGY 6 ABOUT REDTORCH INTRODUCTION #SportOnSocial INTRODUCTION Welcome to the second edition of #SportOnSocial. This annual report by REDTORCH analyses the presence and performance of 35 IOC- recognised International Sport Federations (IFs) on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube. The report includes links to examples of high-performing content that can be viewed by clicking on words in red. Which sports were the highest climbers in our Rankings Table? How did IFs perform at INTRODUCTION PyeongChang 2018? What was the impact of their own World Championships? Who was crowned this year’s best on social? We hope you find the report interesting and informative! The REDTORCH team. 4 RANKINGS TABLE SOCIAL MEDIA RANKINGS TABLE #SportOnSocial Overall International Channel Rank Overall International Channel Rank Rank* Federation Rank* Federation 1 +1 WR: World Rugby 1 5 7 1 19 +1 IWF: International Weightlifting Federation 13 24 27 13 2 +8 ITTF: International Table Tennis Federation 2 4 10 2 20 -1 FIE: International Fencing Federation 22 14 22 22 3 – 0 FIBA: International Basketball Federation 5 1 2 18 21 -6 IBU: International Biathlon Union 23 11 33 17 4 +7 UWW: United World Wrestling 3 2 11 9 22 +10 WCF: World Curling Federation 16 25 12 25 5 +3 FIVB: International Volleyball Federation 7 8 6 10 23 – 0 IBSF: International Bobsleigh and Skeleton Federation 17 15 19 30 6 +3 IAAF: International -

FIFA and the FIRST WORLD CUP by 1900 Soccer Was Well on Its Way to World Domination

THE WORLD CUP SOCCER’S GLOBAL CHAMPIONSHIP he World Cup is international Tsoccer’s championship tournament, and it rules the global sports stage. Award-winning author Matt Doeden explores the history of international soccer and covers the World Cup’s greatest moments, from the Save of the Century to Diego Maradona’s Hand of God goal to the United States Women’s National Team’s dominance. The most shocking goals, the greatest upsets, and the fun and fanfare of soccer’s biggest event are all here. REINFORCED BINDING Matt Doeden J MILLBROOK PRESS · MINNEAPOLIS Copyright © 2018 by Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means— electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review. Millbrook Press A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. 241 First Avenue North Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com. Main body text set in Adobe Garamond Pro Regular 14/19. Typeface provided by Adobe Systems. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Doeden, Matt. Title: The world cup : soccer’s global championship / By Matt Doeden. Description: Minneapolis : Millbrook Press, [2018] | Series: Spectacular sports | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017009220 (print) | LCCN 2017014231 (ebook) | ISBN 9781512498684 (eb pdf) | ISBN 9781512427554 (lb : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: World Cup (Soccer)—Juvenile literature. -

2021-2022 Minutes of Meeting

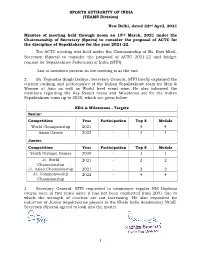

SPORTS AUTHORITY OF INDIA (TEAMS Division) New Delhi, dated 22nd April, 2021 Minutes of meeting held through zoom on 15th March, 2021 under the Chairmanship of Secretary (Sports) to consider the proposal of ACTC for the discipline of Sepaktakraw for the year 2021-22. The ACTC meeting was held under the Chairmanship of Sh. Ravi Mital, Secretary (Sports) to consider the proposal of ACTC 2021-22 and budget request for Sepaktakraw Federation of India (STFI). List of members present in the meeting is at the end. 2. Sh. Yogendra Singh Dahiya, Secretary General, STFI briefly explained the current ranking and performance of the Indian Sepaktakraw team for Men & Women at Asia as well as World level event wise. He also informed the members regarding the Key Result Areas and Milestones set for the Indian Sepaktakraw team up to 2030, which are given below: KRA & Milestones - Targets Senior: Competition Year Participation Top 8 Medals World Championship 2021 - 4 4 Asian Games 2022 - 4 4 Junior: Competition Year Participation Top 8 Medals Youth Olympic Games 2030 - 1 1 Jr. World 2021 - 2 2 Championship Jr. Asian Championship 2021 - 2 2 Jr. Commonwealth 2022 - 4 4 Championship 3. Secretary General, STFI requested to commence regular NIS Diploma course once in two years since it has not been conducted from 2001 due to which the strength of coaches are not increasing. He also requested for induction of Junior Sepaktakraw players in the Khelo India Academies/ NCoE. Secretary (Sports) agreed to look into the matter. 1 4. Thereafter, the ACTC 2021-22 proposal for the discipline of Sepaktakraw was taken up for consideration and total budget of Rs. -

Kausi Käyntiin, Sami Mondolin Mestariksi Sivu 15 Matkalla Tulevaisuuteen Tätä Lukiessanne on Uusi Liittohallitus Valittu

Kausi käyntiin, Sami Mondolin mestariksi sivu 15 Matkalla tulevaisuuteen Tätä lukiessanne on uusi liittohallitus valittu. Tai tarkemmin: allekirjoittanut ja maajoukkueen johtaja/liigasihteeri ovat Risto Spora saaneet kyytiä tai työnsä jatkajiksi virkeät voimat. dellisessä lehdessä kirjoitin pienes- heti loppua. Jos meillä ei ole kykyä näyttää rantaa toimintaansa. Koska me emme toi- tä toiveestani siirtyä takavasemmal- olevamme osaajia, niin uudet harrastajat jää- mi emmekä voi toimia yritysmaailman ta- E le hallitustyöskentelystä ja tiesin jo vät haavistamme. paan osakkailta tai rahoituslaitoksilta lisära- silloin että Tapani Heikkilällä on samat Vaikka liitto on voittoa tavoittelematon hoitusta pyytäen, niin pienet raha- ja hen- ajatukset, mutta minun asiani ei ole niitä yhdistys, hienommin World Darts Federa- kilöresurssit, sisäinen ja ulkoinen vastarin- tuoda julki. Sittemmin Tapsa tarinoi netis- tionin tapaan amerikkalaisittain lausuttuna ta sekä suuri paine välttää ristiriitaisia vies- sä ja kertoi omat ajatuksensa. Samalla meni ns. nonprofit-organisaatio, kohtaamme me tejä, ovat meidän pulmiamme suunnittelun myös tämä pääkirjoitus uusiksi, sillä syys- toiminnassamme kovaa kilpailua ympäris- puutteen ohessa. Näiden pulmien avaajaa kuun tarinoissa oli pääpiirtein samat asiat tössämme. Siinä pärjätäksemme tarvitsem- ja ratkaisijaa kaipaamme. Ehkä hän istuu kuin valmiiksi kirjoitetussa jutussani tähän me osaamista usealta eri osa-alueelta ja toi- jo hallituksessa. sivulle 2. von, että Hämeenlinnan kokouksessa saim- Otan vielä myöhemmin paria asiaa kir- me hallitukseen nimenomaan osaajia eikä Liiga joitukseni raadosta esiin, mutta ensin halu- taaksepäin tuijottajia. Toivon, että saimme Hallitus käsitteli liiga-asiaa kesällä koko- aisin herättää kerhot miettimään liittomme viestikapulan kuljettajia, joilla kapula myös uksessaan Tampereella ja päätyi odottaval- todellista suuntaa. Liitolla ei ole tällä hetkel- pysyy kädessä. le kannalle, kuten moni on jo Tapsan Tari- lä aatteellista johtajaa. -

New Canadians and Sport: a RESOURCE for GRASSROOTS SPORT Contents Foreword

New Canadians and Sport: A RESOURCE FOR GRASSROOTS SPORT Contents Foreword Foreword . .3 This guide has been developed following 2 years of rigorous activity in the Ottawa area. While the examples and programs are solely focused on soccer, Background – Ottawa and ethnicity . .4 many situations can be seen in other sports. Underlying the project was the simple message that sport (soccer) connects people in a way that few other Settlement – How did we find newcomers? . .5 activities can. Learn and Play . .5 Over the course of 2 years (2011-2013), The Ontario Soccer Association (OSA) led an innovative array of soccer programs tirelessly searching for the next Community Day Events. .10 local groups or association to collaborate with. The ‘Thank you’ on page 23 gives a very clear picture of the diversity within which we live. All of these Coaching. .12 groups were drawn to the beautiful game often simply knowing that their kids love the sport. Our future concern as leaders and as parents should be on Mentorship program . .15 keeping these children actively engaged. Referee . .16 The support of the federal government through the Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration Canada made the whole program possible and for that we Soccer in Schools . .18 are very appreciative. As a result of their support and through the positive connection we were able to make with soccer clubs, community groups and By The Numbers . .21 schools we were able to connect: The Program – about Javier, about Audra . .22 • New and experienced coaches and referees with clubs in their area opening up many opportunities to develop their knowledge Thank you. -

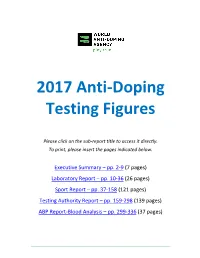

2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Report

2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Please click on the sub‐report title to access it directly. To print, please insert the pages indicated below. Executive Summary – pp. 2‐9 (7 pages) Laboratory Report – pp. 10‐36 (26 pages) Sport Report – pp. 37‐158 (121 pages) Testing Authority Report – pp. 159‐298 (139 pages) ABP Report‐Blood Analysis – pp. 299‐336 (37 pages) ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Executive Summary ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Samples Analyzed and Reported by Accredited Laboratories in ADAMS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Executive Summary is intended to assist stakeholders in navigating the data outlined within the 2017 Anti -Doping Testing Figures Report (2017 Report) and to highlight overall trends. The 2017 Report summarizes the results of all the samples WADA-accredited laboratories analyzed and reported into WADA’s Anti-Doping Administration and Management System (ADAMS) in 2017. This is the third set of global testing results since the revised World Anti-Doping Code (Code) came into effect in January 2015. The 2017 Report – which includes this Executive Summary and sub-reports by Laboratory , Sport, Testing Authority (TA) and Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) Blood Analysis – includes in- and out-of-competition urine samples; blood and ABP blood data; and, the resulting Adverse Analytical Findings (AAFs) and Atypical Findings (ATFs). REPORT HIGHLIGHTS • A analyzed: 300,565 in 2016 to 322,050 in 2017. 7.1 % increase in the overall number of samples • A de crease in the number of AAFs: 1.60% in 2016 (4,822 AAFs from 300,565 samples) to 1.43% in 2017 (4,596 AAFs from 322,050 samples). -

Exploring Certification Programs and Organizational Capacity in Canadian Soccer

Exploring certification programs and organizational capacity in Canadian soccer by Lara D. Schroeder A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master in Arts in Recreation and Leisure Studies Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2019 © Lara D. Schroeder 2019 CERTIFICATION, CAPACITY & CANADIAN SOCCER Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii CERTIFICATION, CAPACITY & CANADIAN SOCCER Abstract Assisting member organizations to achieve certification standards is becoming an activity of interest to many governing bodies who seek to develop capacity within their sport (Van Hoecke, Schoukens & De Knop, 2013). Certification programs aim to both promote and validate organizational development while standardizing programs, policies, and procedures. Sport-based certification is growing as an international phenomenon (e.g., Nichols & Taylor, 2015; Perck, Van Hoecke, Westerbeek, and Breesch, 2016; Relvas, Littlewood, Nesti, Gilbourne & Richardson, 2010). A growing number of governing bodies across Canada are implementing certification through multi-sport or single sport certification programs, either designed and delivered through internal programs or by external agencies. Sport organizations face increasing pressure to professionalize and standardize their program delivery and operations (Van Hoecke et al., 2013). Certification schemes represent one means of quality assurance, yet engaging in certification requires extensive investment of time, resources, and energy which may already be limited in amateur sport organizations (Cope, Haq, Garside, Pannell & Gooders, 2014). -

Complete General Guide

By : Faisal Qureshi LIST OF CONTENT DISCOVERIES LARGEST-HIGHEST-OLDEST-FIRST-IN-THE-WORLD WORLD-COUNTRIES-CAPITALS-CURRENCIES- LANGUAGES RELIGIONS GENERAL, MATH & ANALYTICS BIG HOLY LAND WORLD-FAMOUS-PERSONALITIES-PROFILES NORTH-ATLANTIC-TREATY-ORGANIZATION-OR-NATO LIST OF SECRETARIES GENERALS LIST-OF-SI-UNITS WORLD-FAMOUS-PARLIAMENTS WORLD-IMPORTANT-FAMOUS-DAYS FAMOUS-SPORTS-EVENTS-AND-INFORMATION FAMOUS-WORLD-POLITICAL-PARTIES FOOT-BALL-WORLD-CUPS CRICKET-WORLD-CUP HOCKEY WORLD CUP BASIC-KNOWLEDGE-ABOUT-COMPUTER GENERAL-KNOWLEDGE-OF-SPORTS-AND-GAMES GENERAL-KNOWLEDGE-ABOUT-EARTH WORLD-FAMO ANDES WORLD-HIGHEST-MILTAY-AWARDS NATIONAL-GAMES-OF-WORLD-COUNTRIES WORLD-FAMOUS-NEWS-AGENCIES FAMOUS-BOOKS-AND-THEIR-AUTHORS GENERAL-KNOWLEDGE-ABOUT-UNO GENERAL-KNOWLEDGE-ABOUT-OIC GENERAL-KNOWLEDGE-ABOUT-SAARC FAMOUS-RIVERS-OF-WORLD WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE RELIGIONS-OF-WORLD OLYMPIC-GAMES SAF-GAMES 1 By : Faisal Qureshi DISCOVERIES Galileo was first to discover rotation of earth • Kohler and Milstein discovered monoclonal antibodies. • Photography was invented by Mathew Barry • Albert Sabin invented Polio vaccine (oral) • Dmitry Ivanovich Mendeleyev (Russian) published his first version of periodic table in 1869. • X-ray machine was invented by James Clark • Arthur Campton discovered x-rays and Cosmic rays. • Chadwick discovered Neutron • Telescope was invented by Galileo • Penicillin was discovered by Alexander Fleming • Noble gases discovered by Cavendish • Gun powder was first invented in China • Velocity of light was measured by Michelson • Archimedes gave laws about Floatation of Bodies • Balloon fly up in air according to Archimedes‘s principle • Dr. Christian Bernard was first to perform heart transplant in 1967 in cape town(SA) • First man to receive artificial heart was Dr.