Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

Autonomy and Devolution

AUTONOMY AND DEVOLUTION Innovations in Philippine Governance 2nd ECOGOVERNANCE ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION 20 June 2002 Balay Kalinaw University of the Philippines, Diliman Quezon City ECOGOVERNANCE ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION 20 JUNE 2002 Published in January 2003 by: The Philippine Environmental Governance Program, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Manila in cooperation with the: League of Municipalities of the Philippines and Center for Leadership, Citizenship, and Democracy, National College of Public Administration and Governance, University of the Philippines, Diliman with technical and production support from: The Philippine Environmental Governance Project Produced by the DENR-USAID’s Philippine Environmental Governance Project (EcoGov) through the assistance of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under USAID PCE-I-00-99-00002-00 EcoGov Project No. 4105505-006. The views expressed and opinions contained in this publication are those of the authors and are not intended as statements of policy of USAID or the authors’ parent organization. 2ND ECOGOVERNANCE ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION AUTONOMY AND DEVOLUTION 9:30 A.M. - 12 NOON 20 JUNE 2002 BALAY KALINAW UP DILIMAN, QUEZON CITY AUTONOMY AND DEVOLUTION i Contents Acronyms ..................................................................................... iii Autonomy and Devolution: Innovations in Governance in the Philippines Eleuterio Dumugho, Office of Sen. Aquilino Pimentel .................................................................. 1 Situationer -

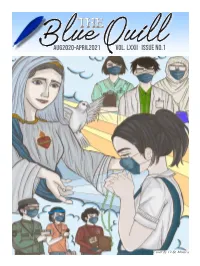

Vol. Lxxii Issue No.1 Aug2020-April2021

THE AUG2020-APRIL2021 VOL. LXXII ISSUE NO.1 Cover by 12-St. Monica 2 news AUG 2020 - APRIL 2021 VOL. LXXII ISSUE NO.1 AUG 2020 - APRIL 2021 VOL. LXXII ISSUE NO.1 news 3 Duterte Signs Pope Francis Anti-Terror backs civil Bill into Law unions for by Rynna Estacio LGBTQ+ President Rodrigo Duterte signed into couples law a highly controversial bill that aims Photo by Gregorio Borja/ AP Photos il unions for same-sex couples, although to broaden the country’s anti-terrorism The statements represent a break by Rynna Estacio he endorsed such legal arrangements campaign. from the Church’s teachings and his when he was archbishop of Buenos Aires. strongest comments yet on the issue. Pope Francis has become the first He also sought to support the church’s It was signed just days before it was Photo by Karl Norman Alonzo/ Presidential Photo leader of the Roman Catholic Church LGBT followers in his public statements effective as law. Nonetheless, Francis’s comments do to support same-sex civil unions. since he was elected pope in March 2013. Executive secretary Salvador Medialdea Over 250 organizations, including the not, in any way, alter the Catholic doc- Republic Act No. 11479, or the Anti-Ter- and presidential spokesman Harry Roque country’s top schools, urged President trine, but represent a remarkable turn for His comments came in an inter- The Ozanne Foundation, which advocates rorism Act of 2020, seeks to strengthen Jr. said the president signed the bill in its Duterte to veto the anti-terrorism bill. a church that has fought against LGBT view in a feature-length documen- for LGBT equality in religious settings, the Human Security Act of 2007, giving entirety. -

Journal No. 75

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES Senate Pasay City Journal SESSION NO. 75 Monday, May 12,2008 FOURTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST REGULAR SESSION SESSION NO. 75 Monday, May 12,2008 CALL TO ORDER Senator Trillanes was unable to attend the session as he is under detention. At 3:28 p.m., the Senate President, Hon. Manny Villar, called the session to order. APPROVAL OF THE JOURNAL PRAYER Upon motion of Senator Pangilinan, there being no objection, the Body dispensed with the reading of the The Body observed a minute of silent prayer. Journal of Session No. 74 and considered it approved. NATIONAL ANTHEM REFERENCE OF BUSINESS The Mapua Concert Singers led the singing of The Secretary of the Senate read the following the national anthem and thereafter rendered the matters and the Chair made the correspondmg referrals: song, entitled Pilipino, Mabuhay Ka. BILLS ON FIRST READING ROLL CALL Senate Bill No. 2257, entitled Upon direction of the Chair, the Secretary of the Senate, Emma Lirio-Reyes, called the roll, to which AN ACT PREVENTING THE MAC- the following senators responded: TURE OR IMPORTATION OF PRODUCTS WITH TOXIC AND Angara, E. J. Honasan, G. B. HAZARDOUS PACKAGING Aquiuo 111, B. S. C. Lapid, M. L. M. Arroyo, J. P. Legarda, L. Introduced by Senator Miriam Defensor Biazon, R. G. Madrigal, M. A. Santiago Cayetano, A. P. C. S. Pangilinan, F. N. Cayetano, C. P. S. Pimentel Jr., A. Q. To the Committees on Trade and Commerce; Defensor Santiago, M. Revilla Jr., R. B. and Health and Demography Ejercito Estrada, J. Villar, M. Enrile, J. -

Liyab-At-Alipato

LIYAB AT ALIPATO MGA KARANASAN SA PAG-OORGANISA SA MGA ESPESYAL NA SONANG PANG-EKONOMIYA SA PILIPINAS Crispin B. Beltran Resource Center Ecumenical Institute for Labor Education and Research Workers Assistance Center sa tulong ng Stichting Onderzoek Multinationale Ondernemingen (SOMO) Liyab at Alipato: Mga Karanasan sa Pag-oorganisa sa mga Espesyal na Sonang Pang-ekonomiya sa Pilipinas © Copyright 2011 Crispin B. Beltran Resource Center, Inc., Ecumenical Institute for Labor Education and Research, Workers Assistance Center. Some rights reserved. Any other copyrighted material used and/or referred to in this book are the properties of their respective owners. First printing, 2011 Recommended Entry: Crispin B. Beltran Resource Center, Inc., Ecumenical Institute for Labor Education and Research Workers Assistance Center ISBN: 978-971-95101-1-6 I. Liyab at Alipato: Mga Karanasan sa Pag-oorganisa sa mga Espesyal na Sonang Pang-ekonomiya sa Pilipinas Book and cover design by ronvil Published by Crispin B. Beltran Reseource Center, Inc. 57 Burgos St., Brgy. Marilag, Project IV, Quezon City, Philippines Ecumenical Institute for Labor Education and Research #15 Anonas St., Unit D-24 Cellar Mansions Barangay Quirino 3-A, Project 3, Quezon City, Philippines Workers Assistance Center Bahay Manggagawa, Indian Mango St., Manggahan Compound Sapa I, 4106 Rosario, Cavite, Philippines Printed by by SJMM Printing Center NILALAMAN 01 Paunang Salita 03 kasaysayan ng mga espesyal na sonang pang-ekonomiya 11 Ang Mga Sonang Pang-ekonomiya sa Pilipinas 31 Apat -

GUEST SPEAKER the ROTARY CLUB of MANILA BOARD of DIRECTORS and Executive Officers 2017-2018

1 Official Newsletter of Rotary Club of Manila 0 balita No. 3728, January 25, 2018 THE ROTARY CLUB OF MANILA GUEST SPEAKER BOARD OF DIRECTORS and Executive Officers 2017-2018 JIMMIE POLICARPIO President TEDDY OCAMPO Immediate Past President CHITO ZALDARRIAGA Vice President BOBBY JOSEPH ISSAM ELDEBS LANCE MASTERS CALOY REYES SUSING PINEDA ART LOPEZ Directors ALVIN LACAMBACAL Secretary NICKY VILLASEÑOR Treasurer DAVE REYNOLDS What’s Inside Sergeant-At-Arms Program 2-3 AMADING VALDEZ Presidential Timeline 4-5 Guest of Honor and Speaker’s Profile 5 Board Legal Adviser Preview of Forthcoming Guest Speakers 7 R.I. Theme RY 2018-2019 7 The Week that Was/ Music Committee 8-12 RENE POLICARPIO Centennial Committee 13 Assistant Secretary New Generations Service 14 Inaugural Meeting 15 International Relations 16-17 NER LONZAGA International Assembly 18-25 JIM CHUA Philippine Rotary 26-27 Assistant Treasurer DISCON 2018 28 Speaker’s Bureau 29-32 News Release 33-34 BOLLIE BOLTON Public Health Nutrition and Child Care 35 Deputy Sgt-at-Arms Advertisement 35-37 Secretariat ANNA KUN TOLEDO Executive Secretary 2 PROGRAM RCM’S 27th for Rotary Year 2017-2018 January 25, 2018, Thursday, 12Noon, New World Makati Hotel Ballroom Officer-In-Charge/ Program Moderator: Rtn. Ricky Trinidad P R O G R A M TIMETABLE 11:30 AM Registration & Cocktails (WINES courtesy of RCM DE/Dir. Bobby Joseph) 12:25 PM Bell to be Rung: Members and Guests are requested to be seated by OIC/Moderator : Rtn. Ricky Trinidad 12:30 PM Call to Order Pres. Jimmie Policarpio Singing of the Republic of the Philippines National Anthem RCM WF Music Chorale Invocation Rtn. -

Covo Holds Visayan Century Awards Gala

BUSINESS FEATURE PHILIPPINE NEWS LEGAL NOTES inside look Entrepreneur Creates 6 28 Congressmen 8 Shortcut to 13 AUG. 1, 2009 Treats for Man's Best With GMA in U.S. Green Card for Friend Trip Doctors H AWAII’ S O NLY W EEKLY F ILIPINO - A MERICAN N EWSPAPER COVO HOLDS VISAYAN CENTURY AWARDS GALA By Serafin COLMENARES s part of its year-long celebration of the Visayan Centennial anniversary in Hawaii, the Congress of Visayan Organiza- tions (COVO) held the Visayan Century Awards Gala on Sun- A day, July 19, 2009 at the Hale Koa hotel. Among the estimated 250 honorees The 12 posthumous awardees were: were honored guests, including City Man- Juan Dionisio Sr. (Oahu), Antonio Ypil aging Director Kirk Caldwell, representing (Oahu), Inocenta Arrogante (Oahu), Ri- the Mayor, and Consul Paul Raymund cardo Labez (Kauai), Zachary Labez Cortes, acting head of post of the Philippine (Kauai), Guadalupe Bulatao (Kauai), Flo- Consulate, and about 50 Visayans from the rentino Hera (Lanai), Paterno Pencerga neighbor islands. (Maui), Pedro Razo (Maui), Agapito and There were three award categories: Catalina Diama (Big Island), Alfred Pa- posthumous, organizational and individual. dayao (Big Island), and Jesus Del Mar (Big The statewide awards were given to indi- Island). The awardees were honored in a viduals (deceased and living) and organi- PowerPoint presentation and awards given zations that have worked towards the to their respective family members and unification of the Visayan community, pro- representatives. moted Visayan culture and traditions, and The three organizational awardees assisted in the growth and development of were: the Balaan Catalina Society (founded (from left) City Managing Director Kirk Caldwell, Jun Colmenares, Emme Tomimbang, Allan Vil- the Visayan and the larger Filipino commu- in 1930), represented by president Leilani laflor, COVO President Margarita Hopkins, Philippine Consul Paul Raymund Cortes and Awards Chair George Carpenter pose for a group photo at the Visayan Century Awards Gala. -

Induced Forest Fires in Region 8 Published April 26, 2020, 11:06 AM by Marie Tonette Marticio

STRATEGIC BANNER COMMUNICATION UPPER PAGE 1 EDITORIAL CARTOON STORY STORY INITIATIVES PAGE LOWER SERVICE April 27, 2020 PAGE 1/ DATE TITLE : DENR enjoins public to report human- induced forest fires in Region 8 Published April 26, 2020, 11:06 AM By Marie Tonette Marticio TACLOBAN City – The Department of Environment and Natural Resources in Region 8 (DENR-8) is urging the public to report any forest fire that could have been caused by careless individuals. “The first line of defense against forest fire is to avoid starting a fire. If it cannot be avoided, make sure you watch over and control it,” Forester Allan Cebuano, Chief, Enforcement Division Chief of DENR 8 noted. It was learned that some of the most recent incidents of forest fires in Eastern Visayas were caused by farming activities such as “kaingin (slash and burn farming)”, smoking of honeycombs to gather honey, cigarette butts, and other forms of activities that involve fire. These reportedly went out of control, and caused the widespread fire in the area. Cebuano added that barangay officials must be informed immediately upon the detection of forest fires. The officials are tasked to report to the concerned disaster risk and reduction management council where a protocol is already in-place for the Bureau of Fire Protection (BFP), as well as other appropriate agencies to respond. Cebuano also warned that unscrupulous individuals who will cause forest fires could be criminally charged under Presidential Decree 705 otherwise known as the “Revised Forestry Code of the Philippines” which provides penalties amounting to not less than P500 to not more than P20,000, and imprisonment of not less than six months or not more than two years. -

ITI Newsletter - May 2020 Online Version

ITI Newsletter - May 2020 Online version Dear Member and Friend of ITI, dear Reader Encouragement, love and support – this is an intangible “commodity” that is continuously needed by all of us. The multitude of letters, documents, videos, etc. that ITI has received are giving hope and connectedness – you can find proof and inspiration on the website of ITI. How will Culture and the Performing Arts recover after Covid-19? A debate with distinguished speakers you will find in the second edition of ResiliArt that is just online live on Thursday, 14 May, 14 to 16 h, Paris time, and can also be watched online at a later point. Also, just now, the Between.Pomiedzy Festival: Kosmopolis 2020 is presenting you a whole festival in Poland – online – from now until 17 May. The North Macedonian of Centre of ITI is offering you a series of online lectures on German Theatre with Thomas Irmer, German dramaturge and theatre researcher, 11 and 12 June. The World Theatre Training Institute AKT-ZENT/ITI is presenting you a three-day online conference in collaboration with the ITI/UNESCO Network for Higher Education in the Performing Arts and Kamal Theatre on 13 to 15 June. The tile is “Challenges of the Mind: An online conference about new dimensions in theatre training”. And much more is in the pipeline, at the moment online. But I ask myself: Online Festival? Online Conference? Online Lecture? Online Future of the Performing Arts? Or rather not? Well, from my own viewpoint is that the live arts – such as music, theatre, dance, music theatre, poetry readings – everything that is happening as an exchange between performers and the members of an audience never vanishes from Earth. -

May 18, 2019 Hawaii Filipino Chronicle 1

MAY 18, 2019 HAWAII FILIPINO CHRONICLE 1 MAY 18, 2019 CANDID PERSPECTIVES LEGAL NOTES ARE WE ASIAN AMERICANS TRUMP ORDERED CRACKDOWN YET? ON VISA OVERSTayS PHILIPPINE ELECTION 2019 COVERAGE VOTE BUYING AN INTEGRAL PART OF PHILIPPINE ELECTIONS - DUTERTE 2 HAWAII FILIPINO CHRONICLEMAY 18, 2019 EDITORIALS FROM THE PUBLISHER Publisher & Executive Editor verybody loves a success story. Charlie Y. Sonido, M.D. Publisher & Managing Editor At a time when immigrants are Immigrant Success Chona A. Montesines-Sonido negatively mischaracterized for Associate Editors political reasons, it’s particular- Edwin QuinaboDennis Galolo Stories Remind Us How ly inspirational and refreshing Contributing Editor to read about successful immi- Belinda Aquino, Ph.D. E Layout Valuable Immigrants grants who are making great contributions to Junggoi Peralta our communities. Photography Are to Our Communities One such individual is Jade Butay, the first Filipino-Amer- Tim Llena ican to be Director of the Hawaii Department of Transpor- Administrative Assistant raveling to a foreign country is always an Lilia Capalad tation (HDOT). Butay was appointed to lead the HDOT by Shalimar Pagulayan eye-opening experience. Travelers can’t help but Governor David Ige and confirmed for this position by the Columnists to compare how their foreign destinations differ Hawaii Senate on March 2 this year. But, as associate editor Carlota Hufana Ader from their own home country: the variations in Edwin Quinabo writes in this issue’s cover story on Butay, Elpidio R. Estioko climate, architecture, air quality, noise, modes of he is not new to the DOT and served as its former Deputy Emil Guillermo transportation, nightlife, leisure activities, cul- Melissa Martin, Ph.D. -

The 1.5˚ Celsius Climate Challenge: Survive and Thrive Together by LUDWIG O

The 1.5˚ celsius climate challenge: survive and thrive together BY LUDWIG O. FEDERIGAN NOVEMBER 15, 2018 HOME / BUSINESS / BUSINESS COLUMNS / THE 1.5˚ CELSIUS CLIMATE CHALLENGE: SURVIVE AND THRIVE TOGETHER LUDWIG O. FEDERIGAN The Climate Change Commission is spearheading this year’s observance of the Global Warming and Climate Change Consciousness Week on November 19 to 25 with the theme “The 1.5˚Celsius Climate Challenge: Survive and Thrive Together.” The observance will highlight the whole-of-government climate action together with sustainable development stakeholders. A week-long conference aims to synergize the country’s vision and policy direction towards green economy and low-carbon future, informed by the latest climate science and technology, knowledge and best practices on climate change resilience. The opening ceremonies on Monday (November 19) at the SMX Convention Center in the Mall of Asia Arena Complex will be led by Secretary Emmanuel M. De Guzman, vice-chair and executive director of the Climate Change Commission. Sen. Loren Legarda, commissioner of the Global Commission on Adaptation, and, at the same time, United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) Global Champion for Resilience and United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Champion for National Adaptation Plans, will deliver the keynote. President Rodrigo Duterte, as chairman of the Climate Change Commission, will share his Vision for a Climate-Resilient Philippines. Invited speakers for the plenary sessions include -

Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila THIRD

Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila THIRD DIVISION G.R. No.72878 April 15, 1988 ALMENDRAS MINING CORPORATION, petitioner, vs. OFFICE OF THE INSURANCE COMMISSION and COUNTRY BANKERS INSURANCE CORPORATION,respondents. Augusto G. Gatmaytan for petitioner. Romeo G. Velasquez for respondents. R E S O L U T I O N FELICIANO, J.: At about two-thirty in the morning of 3 September 1984, the marine cargo vessel LCT "Don Paulo," while on a voyage from Davao to Mariveles, Bataan, was forced ground somewhere in the vicinity of Sogod, Tablas Island, Romblon after having been hit by strong winds and tidal waves brought about by tropical typhoon "Nitang." Later that same day, petitioner Almendras Mining Corporation ("Almendras"), owner of the vessel, executed and filed the corresponding Marine Protest. 1 Subsequently, in a letter dated 6 September 1984, 2 petitioner Almendras formally notified the vessel's insurer, private respondent Country Bankers Insurance Corporation ("Bankers"), of its intention to file a provisional claim for indemnity for damages sustained by the vessel. 3 Immediately following the marine casualty, private respondent Bankers commissioned the services of Audemus Adjustment Corporation, which estimated the insurer's liability at P2,187,983.00, or the equivalent of seventy percent (70%) of all expenses necessary for the repair of the vessel. Private respondent accepted and approved this estimate. Salvage operations on the LCT "Don Paulo" were commenced on 5 September 1984. By 24 September 1984, the vessel had been towed to and docked at the Philippine National Oil Corporation (PNOC) marine facility in Bauan, Batangas where repair work on the same was subsequently performed by the PNOC Marine Corporation.