Generating Procedures and Cardiothoracic Surgery and Anaesthesia —

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Middle Nasal Valve Collapse: a Way to Resolve

Journal of Otolaryngology-ENT Research Case Report Open Access Middle nasal valve collapse: a way to resolve Abstract Volume 10 Issue 3 - 2018 Middle nasal valve collapse is a partial or complete collapsing of soft structures of Dunja Milicic,1 Carolina Serodio2 nasal pyramid, due to negative intranasal pressures resulting in complete anterior nasal 1 obstruction of air-flow. Even though is relatively common, it is often misdiagnosed or Hospital da Luz Arrabida, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Portugal neglected in diagnosis. There are too many suggestions of surgical resolution of the 2Hospital da Luz Póvoa de Varzim, Department of problem, giving an idea that all of them are actually only partially or insufficiently Otorhinolaryngology, Portugal resolving the problem. In this paper a possible solution of middle nasal vault collapse was presented. A Correspondence: Dunja Milicic, Hospital da Luz Arrábida, triangle cartilage grafting with respecting of anatomical and functional principles was Praceta de Henrique Moreira 150, 4400-346 Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal, Tel +351-22 377-6800, suggested. An open rhinoplasty approach by its large exposure was, in our hands, the Email [email protected] election method for resolving the problem. Received: February 01, 2018 | Published: May 21, 2018 Keywords: nasal valve collapse, triangular cartilage, graft, open rhinoplasty Introduction the nostril (lateral alar crura) is usually annoying the patients, by its hardness and cosmetic deformity, even though some authors minimize Collapse -

Dorsal Approach Rhinoplasty Dorsal Approach Rhinoplasty

AIJOC 10.5005/jp-journals-10003-1105 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Dorsal Approach Rhinoplasty Dorsal Approach Rhinoplasty Kenneth R Dubeta Part I: Historical Milestones in Rhinoplasty ABSTRACT Direct dorsal excision of skin and subcutaneous tissue is employed in rhinoplasty cases characterized by thick rigid skin to achieve satisfactory esthetic results, in which attempted repair by more conventional means would most likely frustrate both surgeon and patient. This historical review reminds us of the lesson: ‘History repeats itself.’ Built on a foundation of reconstructive rhinoplasty, modern cosmetic and corrective rhinoplasty have seen the parallel development of both open and closed techniques as ‘new’ methods are introduced and reintroduced again. It is from the perspective of constant evolution in the art of rhinoplasty surgery that the author presents, in Part II, his unique ‘eagle wing’ chevron incision technique of dorsal approach rhinoplasty, to overcome the problems posed by the rigid skin nose. Keywords: Dorsal approach rhinoplasty, Eagle wing incision, Fig. 1: Ancient Greek ‘perikephalea’ to support the Rigid skin nose, External approach rhinoplasty, Historical straightened nose1 milestones. How to cite this article: Dubeta KR. Dorsal Approach and functions of the nose. Refinement of these techniques Rhinoplasty. Int J Otorhinolaryngol Clin 2013;5(1):1-23. seemingly had to await three antecedent developments; Source of support: Nil topical vasoconstriction; topical, systemic and local Conflict of interest: None declared anesthesia; and safe, reliable sources of illumination. The last half of the 20th century has seen the dissemination of INTRODUCTION two of the most important developments in the history of Throughout the ages, numerous techniques of altering, nasal surgery: correcting and more recently, improving the appearance and 1. -

Lung Decortication in Phase III Pleural Empyema by Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (VATS)—Results of a Learning Curve Study

4320 Original Article Lung decortication in phase III pleural empyema by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS)—results of a learning curve study Martin Reichert1, Bernd Pösentrup1, Andreas Hecker1, Winfried Padberg1, Johannes Bodner2,3 1Department of General, Visceral, Thoracic, Transplant and Pediatric Surgery, University Hospital of Giessen, Giessen, Germany; 2Department of Thoracic Surgery, Klinikum Bogenhausen, Munich, Germany; 3Department of Visceral, Transplant and Thoracic Surgery, Center of Operative Medicine, Innsbruck Medical University, Innsbruck, Austria Contributions: (I) Conception and design: M Reichert, J Bodner; (II) Administrative support: A Hecker, W Padberg; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: W Padberg, J Bodner; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: M Reichert, B Pösentrup; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Martin Reichert, MD. Department of General, Visceral, Thoracic, Transplant and Pediatric Surgery, University Hospital of Giessen, Rudolf-Buchheim Strasse 7, 35392 Giessen, Germany. Email: [email protected]. Background: Pleural empyema (PE) is a devastating disease with a high morbidity and mortality. According to the American Thoracic Society it is graduated into three phases and surgery is indicated in intermediate phase II and organized phase III. In the latter, open decortication of the lung via thoracotomy is the gold standard whereas the evidence for feasibility and safety of a minimally-invasive video-assisted thoracoscopic approach is still poor. Methods: Retrospective single-center analysis of patients undergoing surgery for phase III PE from 02/2011 to 03/2015 [n=138, including n=130 VATS approach (n=3 of them with bilateral disease) and n=8 open approach]. -

Core Curriculum for Surgical Technology Sixth Edition

Core Curriculum for Surgical Technology Sixth Edition Core Curriculum 6.indd 1 11/17/10 11:51 PM TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Healthcare sciences A. Anatomy and physiology 7 B. Pharmacology and anesthesia 37 C. Medical terminology 49 D. Microbiology 63 E. Pathophysiology 71 II. Technological sciences A. Electricity 85 B. Information technology 86 C. Robotics 88 III. Patient care concepts A. Biopsychosocial needs of the patient 91 B. Death and dying 92 IV. Surgical technology A. Preoperative 1. Non-sterile a. Attire 97 b. Preoperative physical preparation of the patient 98 c. tneitaP noitacifitnedi 99 d. Transportation 100 e. Review of the chart 101 f. Surgical consent 102 g. refsnarT 104 h. Positioning 105 i. Urinary catheterization 106 j. Skin preparation 108 k. Equipment 110 l. Instrumentation 112 2. Sterile a. Asepsis and sterile technique 113 b. Hand hygiene and surgical scrub 115 c. Gowning and gloving 116 d. Surgical counts 117 e. Draping 118 B. Intraoperative: Sterile 1. Specimen care 119 2. Abdominal incisions 121 3. Hemostasis 122 4. Exposure 123 5. Catheters and drains 124 6. Wound closure 128 7. Surgical dressings 137 8. Wound healing 140 1 c. Light regulation d. Photoreceptors e. Macula lutea f. Fovea centralis g. Optic disc h. Brain pathways C. Ear 1. Anatomy a. External ear (1) Auricle (pinna) (2) Tragus b. Middle ear (1) Ossicles (a) Malleus (b) Incus (c) Stapes (2) Oval window (3) Round window (4) Mastoid sinus (5) Eustachian tube c. Internal ear (1) Labyrinth (2) Cochlea 2. Physiology of hearing a. Sound wave reception b. Bone conduction c. -

Management of Empyema Thoracis

466 Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine Volume 87 August 1994 Section Meetings Management of empyema thoracis John A Odell ChB FRCS(Ed) Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN 55905, USA Keywords: empyema thoracis; drainage of empyema; decortication loculation, particularly posteriorly. The pleural fluid Paper read to pH and glucose level become progressively lower and Cardiothoracic Definitions the LDH level increases. In the third or organizational Section, An empyema thoracis is simply a collection of pus stage, fibroblasts grow into the exudate from both the 27 May 1993 in the pleural space. Some have tried to define it visceral and parietal pleural surfaces to produce an differently, but this is unnecessary; many term a inelastic membrane called the pleural peel or cortex. parapneumonic effusion associated with bacterial pneumonia, lung abscess, or bronchiectasis an Historical empyema whereas others state that only para- perspective pneumonic effusions with positive pleural fluid cultures can be called an Likewise, others Those cases of empyema or dropsy which are treated by empyema1. incision or the cautery, ifthe water or pus flows rapidly all use the term 'complicated parapneumonic effusion' at once, certainly prove fatal. to refer to those effusions that do not resolve without When empyema is treated either by the cautery or incision, tube thoracostomy'. Another term that is frequently if pure and white pus flow from the wound, the patients used, particularly in regions where tuberculosis is recover, but if mixed with blood, slimy and fetid they die. common, is the term 'tuberculous empyema'. However, Hippocrates2 we do not normally classify a straw-coloured effusion from which tubercle bacilli are isolated as an Cardiothoracic surgery probably began with the empyema, nor do we often find thick caseous management of empyema. -

Table of Contents 1

GENERAL THORACIC SURGERY DATABASE v.2.3 TRAINING MANUAL August 2017 Table of Contents 1. Demographics ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Follow Up ........................................................................................................................................................................ 9 3. Admission ..................................................................................................................................................................... 10 4. Pre-Operative Evaluation ............................................................................................................................................. 14 5. Diagnosis (Category of Disease) ................................................................................................................................... 48 6. Procedure ..................................................................................................................................................................... 70 7. Post-Operative Events ................................................................................................................................................ 111 8. Discharge .................................................................................................................................................................... 135 9. Quality Measures ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Endoscopy Matrix

Endoscopy Matrix CPT Description of Endoscopy Diagnostic Therapeutic Code (Surgical) 31231 Nasal endoscopy, diagnostic, unilateral or bilateral (separate procedure) X 31233 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, diagnostic with maxillary sinusoscopy (via X inferior meatus or canine fossa puncture) 31235 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, diagnostic with sphenoid sinusoscopy (via X puncture of sphenoidal face or cannulation of ostium) 31237 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with biopsy, polypectomy or X debridement (separate procedure) 31238 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with control of hemorrhage X 31239 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with dacryocystorhinostomy X 31240 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with concha bullosa resection X 31241 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with ligation of sphenopalatine artery X 31253 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with ethmoidectomy, total (anterior X and posterior), including frontal sinus exploration, with removal of tissue from frontal sinus, when performed 31254 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with ethmoidectomy, partial (anterior) X 31255 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with ethmoidectomy, total (anterior X and posterior 31256 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with maxillary antrostomy X 31257 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with ethmoidectomy, total (anterior X and posterior), including sphenoidotomy 31259 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with ethmoidectomy, total (anterior X and posterior), including sphenoidotomy, with removal of tissue from the sphenoid sinus 31267 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with removal of -

ICD-9-CM Procedures (FY10)

2 PREFACE This sixth edition of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) is being published by the United States Government in recognition of its responsibility to promulgate this classification throughout the United States for morbidity coding. The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, published by the World Health Organization (WHO) is the foundation of the ICD-9-CM and continues to be the classification employed in cause-of-death coding in the United States. The ICD-9-CM is completely comparable with the ICD-9. The WHO Collaborating Center for Classification of Diseases in North America serves as liaison between the international obligations for comparable classifications and the national health data needs of the United States. The ICD-9-CM is recommended for use in all clinical settings but is required for reporting diagnoses and diseases to all U.S. Public Health Service and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (formerly the Health Care Financing Administration) programs. Guidance in the use of this classification can be found in the section "Guidance in the Use of ICD-9-CM." ICD-9-CM extensions, interpretations, modifications, addenda, or errata other than those approved by the U.S. Public Health Service and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are not to be considered official and should not be utilized. Continuous maintenance of the ICD-9- CM is the responsibility of the Federal Government. However, because the ICD-9-CM represents the best in contemporary thinking of clinicians, nosologists, epidemiologists, and statisticians from both public and private sectors, no future modifications will be considered without extensive advice from the appropriate representatives of all major users. -

Icd-9-Cm (2010)

ICD-9-CM (2010) PROCEDURE CODE LONG DESCRIPTION SHORT DESCRIPTION 0001 Therapeutic ultrasound of vessels of head and neck Ther ult head & neck ves 0002 Therapeutic ultrasound of heart Ther ultrasound of heart 0003 Therapeutic ultrasound of peripheral vascular vessels Ther ult peripheral ves 0009 Other therapeutic ultrasound Other therapeutic ultsnd 0010 Implantation of chemotherapeutic agent Implant chemothera agent 0011 Infusion of drotrecogin alfa (activated) Infus drotrecogin alfa 0012 Administration of inhaled nitric oxide Adm inhal nitric oxide 0013 Injection or infusion of nesiritide Inject/infus nesiritide 0014 Injection or infusion of oxazolidinone class of antibiotics Injection oxazolidinone 0015 High-dose infusion interleukin-2 [IL-2] High-dose infusion IL-2 0016 Pressurized treatment of venous bypass graft [conduit] with pharmaceutical substance Pressurized treat graft 0017 Infusion of vasopressor agent Infusion of vasopressor 0018 Infusion of immunosuppressive antibody therapy Infus immunosup antibody 0019 Disruption of blood brain barrier via infusion [BBBD] BBBD via infusion 0021 Intravascular imaging of extracranial cerebral vessels IVUS extracran cereb ves 0022 Intravascular imaging of intrathoracic vessels IVUS intrathoracic ves 0023 Intravascular imaging of peripheral vessels IVUS peripheral vessels 0024 Intravascular imaging of coronary vessels IVUS coronary vessels 0025 Intravascular imaging of renal vessels IVUS renal vessels 0028 Intravascular imaging, other specified vessel(s) Intravascul imaging NEC 0029 Intravascular -

Airway Inflammation in Asthma

ii4 Spoken sessions Spoken sessions ........................................................................... Thorax: first published as on 28 November 2005. Downloaded from of variable airflow obstruction: methacholine PC20,8 mg/ml, increase Airway inflammation in asthma: in FEV1 of 15% or greater following inhalation of 200 mg of salbutamol and/or peak flow amplitude as percent of mean over 14 days of .20%. basic and clinical science Endobronchial biopsies were taken from 11 patients with non- eosinophilic asthma, 12 patients with eosinophilic asthma, and 10 normal control subjects. The patients with non-eosinophilic asthma and S1 INCREASED TACHYKININ LEVELS IN THE AIRWAYS OF six patients with eosinophilic asthma entered a randomised, double ASTHMATIC PATIENTS AND CHRONIC COUGH blinded, placebo controlled cross over study of inhaled mometasone PATIENTS WITH COEXISTENT GASTRO- 400 mg once daily for eight weeks. Patients with eosinophilic asthma OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE had a median 23 bronchial submucosal cells positive for major basic protein per mm2 which was higher than both normal controls (0 cells/ 2 2 R. N. Patterson1, B. T. Johnston1, L. G. Heaney1,2, L. P. A. McGarvey1. mm , p = 0.043) and patients with eosinophilic asthma (4.4 cells/mm , 1Department of Medicine, Queens University Belfast, Belfast, N Ireland; p = 0.016). Submucosal mast cells numbers were not different between 2Regional Respiratory Centre, Belfast City Hospital, Belfast, N Ireland the groups. However airway smooth muscle mast cell numbers were higher in eosinophilic asthma (8 cells/mm2) and non eosinophilic 2 2 Background: Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) may aggra- asthma (9 cells/mm ) compared to normal controls (0 cells/mm , vate airway diseases including asthma and chronic cough. -

Anesthesia for Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery

23 Anesthesia for Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery Edmond Cohen Historical Considerations of Video-Assisted Thoracoscopy ....................................... 331 Medical Thoracoscopy ................................................................................................. 332 Surgical Thoracoscopy ................................................................................................. 332 Anesthetic Management ............................................................................................... 334 Postoperative Pain Management .................................................................................. 338 Clinical Case Discussion .............................................................................................. 339 Key Points Jacobaeus Thoracoscopy, the introduction of an illuminated tube through a small incision made between the ribs, was • Limited options to treat hypoxemia during one-lung venti- first used in 1910 for the treatment of tuberculosis. In 1882 lation (OLV) compared to open thoracotomy. Continuous the tubercle bacillus was discovered by Koch, and Forlanini positive airway pressure (CPAP) interferes with surgi- observed that tuberculous cavities collapsed and healed after cal exposure during video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery patients developed a spontaneous pneumothorax. The tech- (VATS). nique of injecting approximately 200 cc of air under pressure • Priority on rapid and complete lung collapse. to create an artificial pneumothorax became a widely used • Possibility -

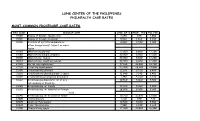

Most Common Procedure Case Rates

LUNG CENTER OF THE PHILIPPINES PHILHEALTH CASE RATES MOST COMMON PROCEDURE CASE RATES RVS CODE DESCRIPTION CASE RATE PROF. FEE HCI FEE 19100 Biopsy of breast; needle core 3,640 840 2,800 19101 Biopsy of breast; incisional 5,560 1,260 4,300 19120 Excision of cyst,fibroadenoma or 8,020 2,520 5,500 other benign breast tissue 1 or more lesion 19160 Mastectomy,partial 22,000 8,800 13,200 19180 Mastectomy,simple,complete 22,000 8,800 13,200 19200 Mastectomy, radical 22,000 8,800 13,200 19240 Mastectomy, modified radical 22,000 8,800 13,200 27125 Partial Hip replacement 37,180 18,480 18,700 27130 Total Hip replacement 53,400 29,400 24,000 31600 Tracheostomy,planned 12,120 6,720 5,400 31601 Tracheostomy,planned;under 2 years 12,540 7,140 5,400 31603 Tracheostomy,emergency procedure 7,140 4,760 2,380 31622 Bronchoscopy,diagnostic, w/ or w/o 10,960 5,460 5,500 cell washing or brushing 31625 Bronchoscopy, w/ biopsy 10,960 5,460 5,500 31635 Bronchoscopy; w/ removal of foreign 18,000 8,400 9,600 body 31640 Bronchoscopy; w/ excision of tumor 30,300 16,800 13,500 32000 Thoracentesis 1,260 840 420 32005 Chemical Pleurodesis 10,540 5,040 5,500 32020 Tube Thoracotomy 7,980 5,320 2,660 32100 Thoracotomy,major 37,800 21,000 16,800 32220 Decortication,pulmonary;total 38,440 19,740 18,700 32225 Decortication,pulmonary;partial 30,300 16,800 13,500 32310 Pleurectomy,parietal 37,800 21,000 16,800 32320 Decortication & parietal pleurectomy 37,800 21,000 16,800 32400 Biopsy of pleura 5,560 1,260 4,300 32402 Biopsy,pleura;open 37,180 18,480 18,700 32405 Biopsy,