Palearctic Birds Special Review by K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes Courtes

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/40114541 Birds of Waza new to Cameroon: corrigenda and addenda Article · January 2000 Source: OAI CITATIONS READS 3 36 2 authors: Paul Scholte Robert Dowsett Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit Private University Consortium Ltd 136 PUBLICATIONS 1,612 CITATIONS 62 PUBLICATIONS 771 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Works of dates of publication View project Dragon Tree Consortium View project All content following this page was uploaded by Paul Scholte on 05 June 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. 2000 29 Short Notes — Notes Courtes Birds of Waza new to Cameroon: corrigenda and addenda In their annotated list of birds of the Waza area, northern Cameroon, Scholte et al. (1999) claimed 11 species for which there were no previous published records from Cameroon “mainly based on Louette (1981)”. In fact, their list included 14 such species, but there are previous published records for most, some missed by Louette (1981), some of which had been listed by Dowsett (1993). We here clarify these records and give additional notes on two other species of the area. Corrigenda Ciconia nigra Black Stork (Dowsett 1993, based on Robertson 1992). Waza. Not claimed as new by Scholte et al. (1999), but the previous record mentioned by them is unpublished (Vanpraet 1977). Platalea leucorodia European Spoonbill (new). Phoenicopterus ruber Greater Flamingo (new). Not claimed as new by Scholte et al. (1999), but the previous record mentioned by them is unidentifiable as to species (Louette 1981). -

FOOTPRINTS in the MUD of AGADEM Eastern Niger's Way

Tilman Musch: FOOTPRINTS IN THE MUD OF AGADEM … FOOTPRINTS IN THE MUD OF AGADEM Eastern Niger’s way towards the Anthropocene Tilman Musch Abstract: Petrified footprints of now extinct rhinos and those of humans in the mud of the former lake Agadem may symbolise the beginning of an epoch dominated by humans. How could such a “local” Anthropocene be defined? In eastern Niger, two aspects seem particularly important for answering this question. The first is the disappearance of the addax in the context of the megafauna extinction. The second is the question how the “natural” environment may be conceived by the local Teda where current Western discussions highlight the “hybridity” of space. Keywords: Anthropocene, Teda, Space, Conservation, addax Agadem is a small oasis in eastern Niger with hardly 200 inhabitants. Most of them are camel breeding nomadic Teda from the Guna clan. Some possess palm trees there. The oasis is situated inside a fossil lake and sometimes digging or even the wind uncovers carbonised fish skeletons, shells or other “things from another time” (yina ŋgoan), as locals call them. But when a traveler crosses the bed of the lake with locals, they make him discover more: Petrified tracks from cattle, from a rhinoceros1 and even from a human being who long ago walked in the lake’s mud.2 1 Locals presume the tracks to be those of a lion. Nevertheless, according to scholars, they are probably the tracks of a rhinoceros. Thanks for this information are due to Louis Liebenberg (Cybertracker) and Friedemann Schrenk (Palaeanthropology; Senckenberg Institute, Frankfurt am Main). -

Scf Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey

SCF PAN SAHARA WILDLIFE SURVEY PSWS Technical Report 12 SUMMARY OF RESULTS AND ACHIEVEMENTS OF THE PILOT PHASE OF THE PAN SAHARA WILDLIFE SURVEY 2009-2012 November 2012 Dr Tim Wacher & Mr John Newby REPORT TITLE Wacher, T. & Newby, J. 2012. Summary of results and achievements of the Pilot Phase of the Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey 2009-2012. SCF PSWS Technical Report 12. Sahara Conservation Fund. ii + 26 pp. + Annexes. AUTHORS Dr Tim Wacher (SCF/Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey & Zoological Society of London) Mr John Newby (Sahara Conservation Fund) COVER PICTURE New-born dorcas gazelle in the Ouadi Rimé-Ouadi Achim Game Reserve, Chad. Photo credit: Tim Wacher/ZSL. SPONSORS AND PARTNERS Funding and support for the work described in this report was provided by: • His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi • Emirates Center for Wildlife Propagation (ECWP) • International Fund for Houbara Conservation (IFHC) • Sahara Conservation Fund (SCF) • Zoological Society of London (ZSL) • Ministère de l’Environnement et de la Lutte Contre la Désertification (Niger) • Ministère de l’Environnement et des Ressources Halieutiques (Chad) • Direction de la Chasse, Faune et Aires Protégées (Niger) • Direction des Parcs Nationaux, Réserves de Faune et de la Chasse (Chad) • Direction Générale des Forêts (Tunis) • Projet Antilopes Sahélo-Sahariennes (Niger) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Sahara Conservation Fund sincerely thanks HH Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, for his interest and generosity in funding the Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey through the Emirates Centre for Wildlife Propagation (ECWP) and the International Fund for Houbara Conservation (IFHC). This project is carried out in association with the Zoological Society of London (ZSL). -

Severe Decline of Large Birds in the Northern Sahel of West Africa: a Long-Term Assessment

Bird Conservation International (2006) 16:353–365. ß BirdLife International 2006 doi: 10.1017/S0959270906000487 Printed in the United Kingdom Severe decline of large birds in the Northern Sahel of West Africa: a long-term assessment JEAN-MARC THIOLLAY Summary The current status of most West African birds is little known and may change quickly with increasing human population pressure and agriculture, road, tourism, hunting and mining developments. Following documented declines of raptors in Sudan and the Southern Sahel zones, I compared the number of birds counted along the same eight extensive transect counts in 1971– 1973 (3,703 km) and 2004 (3,688 km) in arid steppes, acacia woodlands and desert mountains of northern Mali and Niger (Adrar des Iforhas, Aı¨r, Te´ne´re´). The once widespread Ostrich Struthio camelus is now extinct west of Chad. No Arabian Ardeotis arabs and Nubian Bustards Neotis nuba were seen in 2004 (216 in 1970s) nor any Ru¨ ppell’s Griffon Gyps rueppellii and Lappet-faced Vultures Torgos tracheliotus (114 and 96 respectively recorded in the 1970s). From Adrar to Te´ne´re´, just one Egyptian Vulture Neophron percnopterus was recorded in 2004 (vs 75 in 1970s), but it was still common in the oases of Kawar (27 vs 38). These data are exploratory and the current status of the species involved should be further documented. Nevertheless, they are a serious warning about the future of several taxa. Overhunting, aggravated by overgrazing and degradation of acacia woodlands are obvious causes of the collapse of Ostrich and bustards. The near-extinction of wild ungulates, intensified use of cattle, increased disturbance and poisoning of predators may have been critical in the dramatic decline of vultures. -

CMS 25 YEARS Final

A special report to mark the Silver Anniversary of the Bonn Convention on Migratory Species (1979–2004) OF JOURNEYS 25 YEARS Convention on Migratory Species United Nations Environment Programme 25 Years A message from the Secretary-General of the United Nations People have long marvelled at the sight of great flocks, shoals or herds of migratory creatures on the move, or have wondered at that movement’s meaning. Published by the Secretariat of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory animals are not only something spectacular to behold from afar; they Migratory Species of Wild Animals are an integral part of the web of life on Earth. Animal migration is essential for (CMS). healthy ecosystems, contributing to their structure and function and visibly Bonn, Germany 2004 connecting one to the other. It is a basis for activities that create livelihoods and support local and global economies. Migratory animals are among the top © 2004 CMS attractions of ecotourism, contributing to sustainable development and national Information in this publication may be wealth. And in many religious and cultural traditions, they stand out in ritual and quoted or reproduced in part or in full lore passed down from generation to generation. provided the source and authorship is As nomads of necessity, these species are highly susceptible to harm caused acknowledged, unless a copyright by destruction of ecosystems. Migratory animals are also threatened by man- symbol appears with the item. made barriers and by unsustainable hunting and fishing practices, including ISBN 3-937429-03-4 ‘bycatch’ in commercial fisheries. People tend to underestimate the vulnerability DISCLAIMER of migratory species, regarding them as hardy and plentiful. -

Burkina Faso

BURKINA FASO Unité-Progrès-Justice Annuaire des Statistiques sur l'Environnement Année 2009 SOMMAIRE AVANT PROPOS 2 LISTE DES SIGLES ET ABREVIATIONS 3 Définitions de quelques termes et concepts utilisés 5 CONTEXTE GENERAL 12 GENERALITES SUR LE BURKINA FASO 13 CADRE ADMINISTRATIF 14 CONTEXTE SOCIOECONOMIQUE 17 CONTEXTE ENVIRONNEMENTAL 22 CONTEXTE DE L’ANNUAIRE 27 CHAPITRE 1 UTILISATION DES TERRES 29 INTRODUCTION 30 LISTE DES TABLEAUX DU CHAPITRE 31 CHAPITRE 2 AGRICULTURE 46 INTRODUCTION 47 LISTE DES TABLEAUX DU CHAPITRE 48 CHAPITRE 3 FORESTERIE 87 INTRODUCTION 88 LISTE DES TABLEAUX DU CHAPITRE 89 CHAPITRE 4 ELEVAGE 111 INTRODUCTION 112 LISTE DES TABLEAUX DU CHAPITRE 113 CHAPITRE 5 BIODIVERSITE 134 INTRODUCTION 135 LISTE DES TABLEAUX DU CHAPITRE 136 CHAPITRE 6 EAU 155 INTRODUCTION 156 LISTE DES TABLEAUX DU CHAPITRE 157 CHAPITRE 7 DECHETS 189 INTRODUCTION 190 LISTE DES TABLEAUX DU CHAPITRE 191 CHAPITRE 8 TRANSPORTS 203 INTRODUCTION 204 LISTE DES TABLEAUX DU CHAPITRE 205 CHAPITRE 9 ENERGIE 219 INTRODUCTION 220 LISTE DES TABLEAUX DU CHAPITRE 221 CHAPITRE 10 AIR 246 INTRODUCTION 247 LISTE DES TABLEAUX DU CHAPITRE 248 CHAPITRE 11 LE CLIMAT 275 INTRODUCTION 276 LISTE DES TABLEAUX DU CHAPITRE 277 CHAPITRE 12 CATASTROPHES NATURELLES 292 INTRODUCTION 293 LISTE DES TABLEAUX DU CHAPITRE 294 CHAPITRE 13 Santé Environnementale 301 INTRODUCTION 302 LISTE DES TABLEAUX DU CHAPITRE 303 CHAPITRE 14 Comptabilité Environnementale 311 INTRODUCTION 312 LISTE DES TABLEAUX DU CHAPITRE 313 1 Annuaire des Statistiques sur l'Environnement Année 2010 LISTE DES SIGLES -

International Trophy Hunting

International Trophy Hunting March 20, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45615 SUMMARY R45615 International Trophy Hunting March 20, 2019 International trophy hunting is a multinational, multimillion-dollar industry practiced throughout the world. Trophy hunting is broadly defined as the killing of animals for recreation with the Pervaze A. Sheikh purpose of collecting trophies such as horns, antlers, skulls, skins, tusks, or teeth for display. The Specialist in Natural United States imports the most trophies of any country in the world. Congressional interest in Resources Policy trophy hunting is related to the recreational and ethical considerations of hunting and the potential consequences of hunting for conservation. For some, interest in trophy hunting centers on particular charismatic species, such as African lions, elephants, and rhinoceroses. Congress’s Lucas F. Bermejo Research Associate role in addressing international trophy hunting is limited, because hunting is regulated by laws of the range country (i.e., the country where the hunted species resides). However, Congress could address trophy hunting through actions such as regulating trophy imports into the United States or providing funding and technical expertise to conserve hunted species in range countries. International trophy hunting generates controversy because of its potential costs and benefits to conservation, ethical considerations, and its contribution to local economies in range states. Proponents of trophy hunting contend that the practice provides an estimated millions of dollars for the conservation of species in exchange for the hunting of a proportionally small number of individuals. Further, they argue that trophy hunting can create incentives for conserving habitat and ecosystems where hunted animals roam and, in some impoverished areas in range countries, can provide a means of income, employment, and community development. -

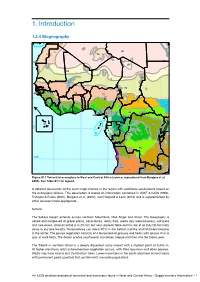

1. Introduction 86

34 85 1. Introduction 86 69 30N 60 1.2.4 Biogeography87 88 93 65 95 98 96 92 97 94 111 99 62 61 35 100 101 115 36 25 70 2 39 83 102 37 38 59 71 1 4 3 4 6 7 5 10 40 44 116 9 103 104 31 12 11 13 16 0 73 41 8 18 14 45 15 17 66 20 47 72 27 43 48 46 42 19 118 112 10S 81 74 50 21 52 82 49 32 26 56 Figure S1.1 Terrestrial ecoregions in West and Central Africa (source: reproduced from Burgess et al. 75 2004). See Table S1.1 for legend. 106 51 119 33 55 64 53 67 63 84 A2 0detailedS description of the eight major biomes in the region with additional subdivisions based on76 29 the ecoregions follows. This description is based on information contained 5in8 WWF6 8& IUCN (1994), 30 Fishpool & Evans (2001), Burgess et al. (2004), and Happold & Lock (2013) and is supplemented57 by 114 other sources where appropriate. 107 54 Terrestrial ecoregions 105 109 113 Sahara Country boundary 22 77 78 The Sahara Desert extends across northern Mauritania, Mali, Niger and Chad. The topography11 7is 28 30S 79 varied and composed of gravel plains, sand dunes, rocky flats, wadis110 (dry watercourses), salt pans 108 23 and rare oases. Annual rainfall is 0–25 mm but very unpredictable and no rain at all may fall for many 0 250 500 1,000 1,500 2,000 2,500 80 years in any one locality. -

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY INVESTING in OUR PLANET Naoko Ishii CEO and Chairperson May 03, 2018

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY INVESTING IN OUR PLANET Naoko Ishii CEO and Chairperson May 03, 2018 Ms Sendashonga Cyrie Global Director International Union for Conservation of Nature Switzerland Dear Ms Cyrie: I am pleased to inform you that I have approved the medium-sized project detailed below: Decision Sought: Medium-sized Project (MSP) Approval GEFSEC ID: 9519 Agency(ies): IUCN Focal Area: Multi Focal Area Project Type: Medium-Sized Project Country(ies): Cameroon Name of Project: Supporting Landscapes Restoration and Sustainable Use of Local Plant Species and Tree Products (Bambusa ssp, lrvingia spp, etc) for Biodiversity Conservation, Sustainable Livelihoods and Emissions Reduction in Cameroon Parent Program: Global: TRI The Restoration Initiative - Fostering Innovation and Integration in Support of the Bonn Challenge Indicative GEF Project Grant: $1,326,146 Indicative Agency Fee: $119,354 Funding Source: GEF Trust Fund Break-down of Indicative Agency Fee Agency Trust Fees committed at Council Fees to be committed at Total (US$) Fund Approval of PFD CEO Approval IUCN GET $47,742 $71,612 $119,354 This approval is subject to the comments made by the GEF Secretariat in the attached document. It is also based on the understanding that the project is in conformity with GEF focal areas strategies and in line with GEF policies and procedures. Chi Attachment: GEFSEC Project Review Document Copy to: Country Operational Focal Point, GEF Agencies, ST AP, Trustee 1818 H Street, NW D Washington, DC 20433 D USA Tel:+ I (202) 473 3202 - Fax:+ I -

Join the WAOS and Support the Future Availability of Free Pdfs on This Website

West African Ornithological Society Société d’Ornithologie de l’Ouest Africain Join the WAOS and support the future availability of free pdfs on this website. http://malimbus.free.fr/member.htm If this link does not work, please copy it to your browser and try again. If you want to print this pdf, we suggest you begin on the next page (2) to conserve paper. Devenez membre de la SOOA et soutenez la disponibilité future des pdfs gratuits sur ce site. http://malimbus.free.fr/adhesion.htm Si ce lien ne fonctionne pas, veuillez le copier pour votre navigateur et réessayer. Si vous souhaitez imprimer ce pdf, nous vous suggérons de commencer par la page suivante (2) pour économiser du papier. February / février 2010 2000 29 Short Notes — Notes Courtes Birds of Waza new to Cameroon: corrigenda and addenda In their annotated list of birds of the Waza area, northern Cameroon, Scholte et al. (1999) claimed 11 species for which there were no previous published records from Cameroon “mainly based on Louette (1981)”. In fact, their list included 14 such species, but there are previous published records for most, some missed by Louette (1981), some of which had been listed by Dowsett (1993). We here clarify these records and give additional notes on two other species of the area. Corrigenda Ciconia nigra Black Stork (Dowsett 1993, based on Robertson 1992). Waza. Not claimed as new by Scholte et al. (1999), but the previous record mentioned by them is unpublished (Vanpraet 1977). Platalea leucorodia European Spoonbill (new). Phoenicopterus ruber Greater Flamingo (new). -

Oil in the Sahara: Mapping Anthropogenic Threats to Saharan Biodiversity from Space

Oil in the Sahara: mapping anthropogenic threats to Saharan biodiversity from space Clare Duncan1, Daniela Kretz1,2, Martin Wegmann3,4, Thomas Rabeil5 and Nathalie Pettorelli1 rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org 1Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London NW1 4RY, UK 2BayCEER, University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth 95440, Germany 3Department of Remote Sensing, University of Wu¨rzburg, Campus Hubland Nord 86, Wu¨rzburg 97074, Germany 4German Remote Sensing Data Center, German Aerospace Center, Oberpfaffenhofen 82234, Germany 5Sahara Conservation Fund, Niamey, Republic of Niger Research Deserts are among the most poorly monitored and understood biomes in the world, with evidence suggesting that their biodiversity is declining Cite this article: Duncan C, Kretz D, fast. Oil exploration and exploitation can constitute an important threat to Wegmann M, Rabeil T, Pettorelli N. 2014 Oil in fragmented and remnant desert biodiversity, yet little is known about the Sahara: mapping anthropogenic threats to where and how intensively such developments are taking place. This lack of information hinders local efforts to adequately buffer and protect desert Saharan biodiversity from space. Phil. wildlife against encroachment from anthropogenic activity. Here, we Trans. R. Soc. B 369: 20130191. investigate the use of freely available satellite imagery for the detection of http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0191 features associated with oil exploration in the African Sahelo-Saharan region. We demonstrate how texture analyses combined with Landsat data One contribution of 9 to a Theme Issue can be employed to detect ground-validated exploration sites in Algeria and Niger. Our results show that site detection via supervised image classi- ‘Satellite remote sensing for biodiversity fication and prediction is generally accurate. -

NL1 (Icke-Tättingar) Ver

Nr Vetenskapligt namn Engelskt namn Svenskt namn (noter) 1 STRUTHIONIFORMES STRUTSFÅGLAR 2 Struthionidae Ostriches Strutsar 3 Struthio camelus Common Ostrich struts 4 Struthio molybdophanes Somali Ostrich somaliastruts 5 6 RHEIFORMES NANDUFÅGLAR 7 Rheidae Rheas Nanduer 8 Rhea americana Greater Rhea större nandu 9 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea mindre nandu 10 11 APTERYGIFORMES KIVIFÅGLAR 12 Apterygidae Kiwis Kivier 13 Apteryx australis Southern Brown Kiwi sydkivi 14 Apteryx mantelli North Island Brown Kiwi brunkivi 15 Apteryx rowi Okarito Kiwi okaritokivi 16 Apteryx owenii Little Spotted Kiwi mindre fläckkivi 17 Apteryx haastii Great Spotted Kiwi större fläckkivi 18 19 CASUARIIFORMES KASUARFÅGLAR 20 Casuariidae Cassowaries, Emu Kasuarer 21 Casuarius casuarius Southern Cassowary hjälmkasuar 22 Casuarius bennetti Dwarf Cassowary dvärgkasuar 23 Casuarius unappendiculatus Northern Cassowary enflikig kasuar 24 Dromaius novaehollandiae Emu emu 25 26 TINAMIFORMES TINAMOFÅGLAR 27 Tinamidae Tinamous Tinamoer 28 Tinamus tao Grey Tinamou grå tinamo 29 Tinamus solitarius Solitary Tinamou solitärtinamo 30 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou svart tinamo 31 Tinamus major Great Tinamou större tinamo 32 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou vitstrupig tinamo 33 Nothocercus bonapartei Highland Tinamou höglandstinamo 34 Nothocercus julius Tawny-breasted Tinamou brunbröstad tinamo 35 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou kamtinamo 36 Crypturellus berlepschi Berlepsch's Tinamou sottinamo 37 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou askgrå tinamo 38 Crypturellus soui