Problematising Theology and Marginality in Bengal's Hinduism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banians in the Bengal Economy (18Th and 19Th Centuries): Historical Perspective

Banians in the Bengal Economy (18th and 19th Centuries): Historical Perspective Murshida Bintey Rahman Registration No: 45 Session: 2008-09 Academic Supervisor Dr. Sharif uddin Ahmed Supernumerary Professor Department of History University of Dhaka This Thesis Submitted to the Department of History University of Dhaka for the Degree of Master of Philosophy (M.Phil) December, 2013 Declaration This is to certify that Murshida Bintey Rahman has written the thesis titled ‘Banians in the Bengal Economy (18th & 19th Centuries): Historical Perspective’ under my supervision. She has written the thesis for the M.Phil degree in History. I further affirm that the work reported in this thesis is original and no part or the whole of the dissertation has been submitted to, any form in any other University or institution for any degree. Dr. Sharif uddin Ahmed Supernumerary Professor Department of History Dated: University of Dhaka 2 Declaration I do declare that, I have written the thesis titled ‘Banians in the Bengal Economy (18th & 19th Centuries): Historical Perspective’ for the M.Phil degree in History. I affirm that the work reported in this thesis is original and no part or the whole of the dissertation has been submitted to, any form in any other University or institution for any degree. Murshida Bintey Rahman Registration No: 45 Dated: Session: 2008-09 Department of History University of Dhaka 3 Banians in the Bengal Economy (18th and 19th Centuries): Historical Perspective Abstract Banians or merchants’ bankers were the first Bengali collaborators or cross cultural brokers for the foreign merchants from the seventeenth century until well into the mid-nineteenth century Bengal. -

1. Textbook Regimes: Overall Analysis

TEXTBOOK REGIMES a feminist critique of nation and identity an overall analysis Research Team Dipta Bhog Disha Mullick Purwa Bharadwaj Jaya Sharma Project Coordinator Dipta Bhog CONTENTS Gender in Education: Opening up the Field 1 An Analysis of Language Textbooks 32 Prologue 33 Forging a Vocabulary for the Nation 39 The Tussle between Tradition and Modernity 75 Romantic Visions of Labour: Class and Gender in the Textbook 99 Textbook Patterns of Violence 111 Marking the Body 127 An Analysis of Social Science Textbooks 142 Interrogating Power in History 143 Locked Within Colonial and Development Paradigms: A Reading of Geography Textbooks 193 Creating the Male and Female Citizen: The Norm of Civics Textbooks 209 An Analysis of Moral Science, Physical and Adolescent Education Textbooks 220 References 265 Annexures 1. Parliamentary Debate on Hindi Textbooks 269 2. Press Statement on NACO Adolescence Education material 271 3. Tables for Analysis of Textbooks 274 4. Textbooks Analysed 283 5. Research Partners 290 An Overall Analysis 1 Gender in Education: Opening up the Field … I am your mother. Not only yours, but also the mother of your ancestors. I am Ganga. Ganga, meaning, I give speed to that which can move even a little. I have descended on this earth primarily to give speed, that is why I am named Ganga. I desire to serve others incessantly… I bear witness - to penance and meditation [sadhana], to the sacrifice of lives into the holy fire for the protection of the country, and to the service of those who are troubled and poor. On my banks, a great civilisation has grown because of these sacrificial ascetics, and I have seen myself as an intrinsic part of this civilisation. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

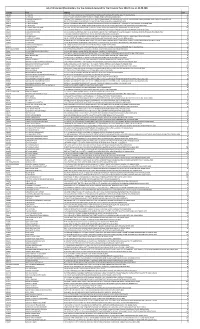

Final Dividend for the Year 2013-2014 As on 31-03-2021

Oriental Carbon & Chemicals Limited Unpaid Dividend Details for Final Dividend for the Year 2013-2014 As on 31-03-2021 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NAMES & ADDRESS OF THE SHARE NO. OF Amount HOLDER SHARES (RS.) SR NO FOLIO NO. WARRANTNO --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------. 1 B090156 2 BANWARI LAL GOYAL 300 1500.00 C/O GOYAL OIL MILL IND. NEAR BUS STAND CHOMU DIST. JAIPUR 2 C000281 3 SURESH KUMAR PRABHUDAS 34 170.00 CHUDASAMA C/O P.N.CHUDASAMA DHANJI BLDG MANI BHAI CHOWK SAVARKUNDALA 3 G000163 5 RAM CHANDRA GAUR 8 40.00 GAYATRI NILAY 78-79,CHURCH ROAD VISHNUPURI,ALIGANJ LUCKNOW 4 M000426 6 MAHENDRA MANSUKHLAL MODY 10 50.00 B/61, GANGA NAGAR SOCIETY NR. TECKARAWALA SCHOOL PALANPUR PATIA, RANDER ROAD SURAT-9 5 M005151 7 MAFATLAL TRIBHOVANDAS PATEL 100 500.00 16A, TRIDEV PARK SOCIETY MADHEVNAGAR, TEKARA VASTRAL ROAD AHMEDABAD 6 M090099 8 JAGAT RAM MOTWANI 2000 10000.00 C/O SHARDA CYCLE AGENCY, CONGRESS COMPLEX, SHOP NO. 2, BUGHAR ROAD SHAHDOL 7 N000160 9 LALITA NATANI 4 20.00 C-56,PUNCH SHEEL COLONY BH.BAKE HOME NEAR OLD OCTROI NAKA AJMER ROAD JAIPUR 8 V000420 11 NEELU VARMA 4 20.00 C/O MR SURAJ PRAQSAD RASTOGI 2/419 KHATRANA FARURKHABAD U P 9 A000026 12 GULABCHAND AJMERA 52 260.00 RAJPATH CHHOTA BAZAR P O SAMBHAR LANE RAJASTHAN 10 A000120 13 RAVI KRISHANA AGARWAL 50 250.00 PREM KUNJ MAIN ROAD MOTIHARI CHAMPARAN 11 A000150 14 SUBASH CHANDER AGGARWAL 4 20.00 C/O KASHMIRI LALL AGGARWAL & BROS ENGINEERS -

Obstacles to Womens' Participation in the Politics of Bangladesh

Obstacles to Womens’ Participation in the Politics of Bangladesh (This dissertation has been prepared for the fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Political science) Supervised by Dr. Nelofar Parvin Professor Department of Political Science University of Dhaka Submitted by: Ishrat Jahan Reg. No: 205 Session: 2008-09 Department of Political science University of Dhaka June, 2014 i Obstacles to Womens’ Participation in the Politics of Bangladesh DECLARATION This dissertation is prepared to submit to the Department of Political Science, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh to fulfill the condition of the Masters of Philosophy (M Phil) program. The material embodied in this thesis is original and has not been submitted in part or full for any other Diploma or Degree of this or any other University or Institution. Ishrat Jahan Registration no: 205 Academic Session: 2008-2009 Department of Political Science University of Dhaka Dhaka-1000 Bangladesh April, 2014 ii University of Dhaka Faculty of Social Sciences Department of Political Science CERTIFICATE It is my pleasure to introduce Most. an M Phil research fellow of the Department of Political science, University of Dhaka has prepared her M Phil dissertation on “Obstacles to women’s participation in the politics of Bangladesh” under my supervision. This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (M.Phil) in Political Science, the University of Dhaka, during the session 2008- 2009. Supervisor Dr. Nelofar Parvin Professor -

Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title Accno Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks

www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks CF, All letters to A 1 Bengali Many Others 75 RBVB_042 Rabindranath Tagore Vol-A, Corrected, English tr. A Flight of Wild Geese 66 English Typed 112 RBVB_006 By K.C. Sen A Flight of Wild Geese 338 English Typed 107 RBVB_024 Vol-A A poems by Dwijendranath to Satyendranath and Dwijendranath Jyotirindranath while 431(B) Bengali Tagore and 118 RBVB_033 Vol-A, presenting a copy of Printed Swapnaprayana to them A poems in English ('This 397(xiv Rabindranath English 1 RBVB_029 Vol-A, great utterance...') ) Tagore A song from Tapati and Rabindranath 397(ix) Bengali 1.5 RBVB_029 Vol-A, stage directions Tagore A. Perumal Collection 214 English A. Perumal ? 102 RBVB_101 CF, All letters to AA 83 Bengali Many others 14 RBVB_043 Rabindranath Tagore Aakas Pradeep 466 Bengali Rabindranath 61 RBVB_036 Vol-A, Tagore and 1 www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks Sudhir Chandra Kar Aakas Pradeep, Chitra- Bichitra, Nabajatak, Sudhir Vol-A, corrected by 263 Bengali 40 RBVB_018 Parisesh, Prahasinee, Chandra Kar Rabindranath Tagore Sanai, and others Indira Devi Bengali & Choudhurani, Aamar Katha 409 73 RBVB_029 Vol-A, English Unknown, & printed Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(A) Bengali Choudhurani 37 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(B) Bengali Choudhurani 72 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Aarogya, Geetabitan, 262 Bengali Sudhir 72 RBVB_018 Vol-A, corrected by Chhelebele-fef. Rabindra- Chandra -

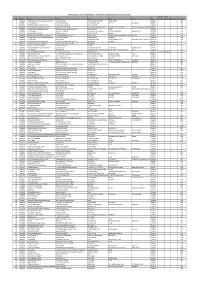

For the Dividend Declared for the Financial Year 2012-13 As on 12.09.2017

List of Unclaimed Shareholders: For the dividend declared for the Financial Year 2012-13 as on 12.09.2017 FOLIO NO NAME ADDRESS AMT A04314 A B FONTES 104 IVTH CROSS KALASIPALYAM NEW EXTENSION BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560002,INDIA 25 A17671 A C SRAJAN 66 LUZ CHURCH ROAD MYLAPORE CHENNAI CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,PIN-600004,INDIA 180 D00252 A DHAKSHINAMOORTHY PARTNER V M C TRADERS STOCKISTS OF A C LTD 6/10 MARIAMMAN KOIL RAMANATHAPURAM DT RAMANATHAPURAM RAMNAD,TAMIL NADU,PIN-623501,INDIA 90 A02076 A JANARDHAN 8/1101 SESHAGIRINIVAS NEW ROAD COCHIN COCHIN ERNAKULAM,KERALA,PIN-682002,INDIA 25 A02270 A K BHATTACHARYA UNITED COMMERCIAL BANK MATA ANANDA NAGAR SHIVALA HOSPITAL VARANASI U P VARANASI,UTTAR PRADESH,PIN-221001,INDIA 25 A03705 A K NARAYANA C/O A K KESAUACHAR 451 TENTH CROSS GIRINAGAR SECOND PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560085,INDIA 25 P00351 A K RAMACHANDRAPRABHU 'PAVITRA' NO 949 24TH MAIN ROAD J P NAGAR II PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560078,INDIA 360 A17411 A KALPAKAM NARAYAN C/O V KAMESWARARAO 7-6-108 ENUGULAMALAL STREET SRIKAKULAM (A.P.) SRIKAKULAM,ANDHRA PRADESH,PIN-532001,INDIA 18 A03555 A LAKSHMINARAYANA C/O G ARUNACHALAM RANA PLOT NO 30 LEPAKSHI COLONY WEST MARREDPALLY SECUNDERABAD HYDERABAD,ANDHRA PRADESH,PIN-500026,INDIA 25 A04366 A M DAVID 1 MISSION COMPOUND AJMER ROAD JAIPUR JAIPUR,RAJASTHAN,PIN-302006,INDIA 25 M00394 A MURUGESAN 3 A D BLOCK V G RAO NAGAR EXTENSION KATPADI P O VELLORE N A A DT VELLORE NORTH ARCOT,TAMIL NADU,PIN-632007,INDIA 23 A17672 A N VENKATALAKSHMI 361 XI A CROSS 29TH MAIN J -

The Black Hole of Empire

Th e Black Hole of Empire Th e Black Hole of Empire History of a Global Practice of Power Partha Chatterjee Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2012 by Princeton University Press Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chatterjee, Partha, 1947- Th e black hole of empire : history of a global practice of power / Partha Chatterjee. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-15200-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)— ISBN 978-0-691-15201-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Bengal (India)—Colonization—History—18th century. 2. Black Hole Incident, Calcutta, India, 1756. 3. East India Company—History—18th century. 4. Imperialism—History. 5. Europe—Colonies—History. I. Title. DS465.C53 2011 954'.14029—dc23 2011028355 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Th is book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Pro Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To the amazing surgeons and physicians who have kept me alive and working This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Illustrations ix Preface xi Chapter One Outrage in Calcutta 1 Th e Travels of a Monument—Old Fort William—A New Nawab—Th e Fall -

Raishahi Zamindars: a Historical Profile in the Colonial Period [1765-19471

Raishahi Zamindars: A Historical Profile in the Colonial Period [1765-19471 Thesis Submitted to the University of North Bengal, Darjeeling, India for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, History by S.iVI.Rabiul Karim Associtate Professor of Islamic History New Government Degree College Rajstiahi, Bangladesh /^B-'t'' .\ Under the Supervision of Dr. I. Sarkar Reader in History University fo North Bengal Darjeeling, West Bengal India Janiary.2006 18^62/ 2 6 FEB 4?eP. 354.9203 189627 26 FEB 2007 5. M. Rahiul Karitn Research Scholar, Associate Professor, Department of History Islamic History University of North Bengal New Government Degree College Darjeeling, West Bengal Rajshahi, Bangladesh India DECLARATION I hereby declare that the Thesis entitled 'Rajshahi Zamindars: A Historical Profile in the Colonial Period (1765-1947)' submitted by me for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of the Universit\' of North Bengal, is a record of research work done by me and that the Thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any other Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship and similar other tides. M^ Ro^JB^-vvA. VxQrVvvv S. M. Rabiul Karim (^ < o t • ^^ Acknowledgment I am grateful to all those who helped me in selecting such an interesting topic of research and for inspiring me to complete the present dissertation. The first person to be remembered in this connection is Dr. I. Sarkar, Reader, Department of History, University of North Bengal without his direct and indirect help and guidance it would not have been possible for me to complete the work. He guided me all along and I express my gratitude to him for his valuable advice and method that I could follow in course of preparation of the thesis. -

Malda Training Diary

Page 1 of 1 ATI Monograph 13/2006 For restricted circulation only A Probationer’s Training Diary COVER PAGE P. Bhattacharya Learning to Serve Administrative Training Institute Page 2 of 2 Government of West Bengal Page 3 of 3 ATI Monograph 13/2006 For restricted circulation A Probationer’s Training Diary TITLE PAGE P. Bhattacharya Learning to Serve Administrative Training Institute Government of West Bengal Page 4 of 4 Block FC, Bidhannagar (Salt Lake) Kolkata-700106 Page 5 of 5 PREFACE New entrants to the Indian Administrative Service and the West Bengal Civil Service (Executive) have to maintain a Training Diary as part of their district training. While supervising their work in the districts, the ATI faculty has found that in the majority of cases the probationers do not maintain their diaries properly, although these are intended to be records of the details of the training they undergo so that superior officers can check whether they have assimilated the proper lessons from the exposure in the field. During interactions with their Counsellors in the ATI, the trainees have complained that they are handicapped by not having an example to follow. A similar handicap has been reported regarding writing reports of enquiries assigned to probationers in the district. In view of this feedback, the ATI is publishing the diary I maintained in detail as probationer in Malda in 1972, trusting that it will provide civil service probationers with an example of how a training diary can be maintained. We were supposed to send the National Academy of Administration an official training diary and also maintain a personal one. -

Share Liable to Be Transferres to IEPF Lying in UNCLAIMED SUSPENSE ACCOUNT

SHARES LIABLE TO BE TRANSFERRED TO IEPF LYING IN UNCLAIMED SUSPENSE ACCOUNT Second Third S.No Folio Name Add1 Add2 Add3 Add4 PIN Holder Holder Delivery Shares 1 000010 HARENDRA KUMAR MAGANLAL MEHTA C/O SHRINAGAR 1198 CHANDNI CHOWK DELHI 110006 110006 0 480 2 000013 N S SUNDARAM 9B CLEMENS ROAD POST BOX NO 480 VEPERY CHENNAI 7 600007 0 210 3 000024 BABUBHAI RANCHHODLAL SHAH 153-D KAMLA NAGAR, DELHI-110 007. 110007 0 210 4 000036 CHANDRAKANT RAOJIBHIA AMIN M/S APAJI AMIN & CO CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS 1299/B/1 LAL DARWAJA NEAR DR K M SHAH S HOSPITAL380001 0 615 5 000042 CHAMPAKLAL ISHWARLAL SHAH 2/4456 SHIVDAS ZAVERZIS SORRI SAGRAMPARA SURAT 395002 0 7 6 000048 K V SIVANNA 181/50 4TH CROSS VYALIKAVAL EXTENSION P O MALLESWARAM BANGALORE 3 560003 0 210 7 000052 NARAYANDAS K DAGA KRISHNA MAHAL MARINE DRIVE MUMBAI 1 400001 0 210 8 000080 MANGALACHERIL SAMUEL ABRAHAM AVT RUBBER PRODUCTS LTD PLOT NO 14-C COCHIN EXPORT PROCESSING ZONE COCHIN 682030 0 502 9 000089 RAMASWAMY PILLAI RAMACHANDRAN 1 PATULLOS ROAD MOUNT ROAD CHENNAI 2 600002 0 435 10 000134 P A ANTONY JOSEALAYAM MUNDAKAPADAM P O ATHIRAMPUZHA DIST-KOTTAYAM KERALA STATE686562 0 210 11 000168 S KOTHANDA RAMAN NAYANAR 11 MADHAVA PERUMAL KOVIL ST MYLAPORE CHENNAI 600004 0 435 12 000171 JETHALAL PANJALAL PAREKH D K ARTS &SCIENCE COLLEGE JAMNAGAR 361001 0 67 13 000173 SAJINI TULSIDAS DASWANI 24 KAHUN ROAD POONA 1 411001 0 1510 14 000226 KRISHNAMOORTY VENNELAGANTI HEAD CASHIER STATE BANK OF INDIA P O GUDUR DIST NELLORE 524101 0 435 15 000227 HAR PRASAD PROPRIETOR M/S GORDHAN DASS SHEONARAINKATRA -

Date of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 09-AUG-2018

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L24110MH1956PLC010806 Prefill Company/Bank Name CLARIANT CHEMICALS (INDIA) LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 09-AUG-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 3803100.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) THOLUR P O PARAPPUR DIST CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A J DANIEL AJJOHN INDIA Kerala 680552 5932.50 02-Oct-2019 TRICHUR KERALA TRICHUR 3572 unpaid dividend INDAS SECURITIES LIMITED 101 CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A J SEBASTIAN AVJOSEPH PIONEER TOWERS MARINE DRIVE INDIA Kerala 682031 192.50 02-Oct-2019 3813 unpaid dividend COCHIN ERNAKULAM RAMACHANDRA 23/10 GANGADHARA CHETTY CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A K ACCHANNA INDIA Karnataka 560042 3500.00 02-Oct-2019 PRABHU