Photo Enlarged by 191%

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stanford Daily an Independent Newspaper

The Stanford Daily An Independent Newspaper VOLUME 199, NUMBER 36 99th YEAR MONDAY, APRIL 15, 1991 Electronic mail message may be bylaws violation By Howard Libit Staff writer Greek issues Over the weekend, campaign violations seemed to be the theme of the Council of Presidents and addressed in ASSU Senate races. Hearings offi- cer Jason Moore COP debate said the elec- By MirandaDoyle tions commis- Staff writer sion will look into vio- possible Three Council of Presi- lations by Peo- dents slates debated at the pie's Platform Sigma house last candidatesand their supporters of Kappa night, answering questions several election bylaws that ranging from policies revolve around campaigning toward Greek organizations through electronic mail. to the scope ofASSU Senate Students First also complained debate. about the defacing and removing Beth of their fliers. The elec- Morgan, a Students of some First COP said will be held Wednesday and candidate, tion her slate plans to "fight for Thursday. new houses to be built" for Senate candidate Nawwar Kas- senate fraternities and work on giv- rawi, currently a associate, ing the Interfraternity sent messages yesterday morning Council and the Intersoror- to more than 2,000 students via ity Council more input in electronic urging support for mail, decisions concerning frater- the People's Platform COP Rajiv Chandrasekaran — Daily "Stand and Deliver" senate nities and sororities. First lady Barbara Bush was one of many celebrities attending this weekend's opening ceremonies for the Lucile Salter Packard Chil- slate, member ofthe candidates and several special fee MaeLee, a dren's Hospital. She took time out from a tour of the hospital to meet two patients, Joshua Evans, 9, and Shannon Brace, 4. -

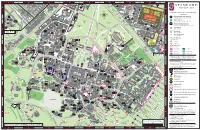

2016-2017 Directory Map with Index 09292016

S AN M AT EO DR M R BRYANT ST D A Y L RAMONA ST TASSO ST W E URBAN LN HERMOSA WY O R O U MELVILLE AV D A L L BUILDING GRID Poplar F-5 Oval, The F/G-8 N Y NeuroscienceQUARRY RD 30 Alta Road K-3 Post Office I-8 PAC 12 Plaza E-12 A B Health Center 08 Panama Mall: Housing Assignments Office H-7 Press Building I-7 Papua New Guinea Sculpture Garden I-6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Advanced Medicine Center: ASC, Cancer Center C-5/6 Psychiatry B-8 Rehnquist Courtyard J-9 COWPER Anderson Collection D-8 Puichon G-2 Roble Field (on Roble Field Garage) H-5/6 WAVERLEY ST Hoover Sheraton PALO RD Arrillaga Alumni Center F-10 Recycling Center G-13 Rodin Sculpture Garden E-7/8 N Neuroscience Hoover William R. KELLOGG AV Art Gallery G-9 Red Barn I-2 Serra Grove G-7 SANTA RITA AV L Pavilion Hotel VIA PUEBLO Serra Shriram Center Artist's Studio K-3 Redwood Hall F-5 SEQ Courtyard G-6 BRYANT ST Pavilion Hewlett D Health Center L-1A Automotive Innovation Facility F-2 Rogers: The Bridge Peer Counseling Center J-7 Taylor Grove, Chuck E-11/12 EL CAMINO REAL EVERETT HIGH ST Downtown Grove SERRA MALL R Garage Bioengineering & U Teaching Bambi H-5/6 Science Teaching and Learning Center (Old Chemistry Building) F-7 Terman Site H-6 (see INSET 1 W A O Sequoia Barnum Center I-8/9 Sequoia Hall G-7 Toyon Grove D-10/11 LYTTON AVE Palo Alto Westin Chemical Engineering SpilkerHIGH ST E H Center B Barnes G-2 Serra (589 Capistrano Way) J-7 West Oval Grove F/G-8 RAMONA ST at upper left) L EMERSON ST S A C Hotel Hall Bechtel International Center J-7 SHC-LPCH Steam Plant -

Stanford University Alumni Collection SC1278

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8qz2ggh No online items Guide to the Stanford University Alumni Collection SC1278 Jenny Johnson & Presley Hubschmitt The Stanford Alumni Collection was created as part of the Stanford Alumni Legacy Project, which was initially funded by the Stanford Associates Grant (awarded by the Stanford Alumni Association in 2014). Department of Special Collections and University Archives Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Stanford University SC1278 1 Alumni Collection SC1278 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Stanford University Alumni Collection Identifier/Call Number: SC1278 Physical Description: 23.75 Linear Feet(38 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1889-2016 Scope and Contents The Stanford Alumni Collection consists of letters, email, texts, student scrapbooks, photographs, websites, audio and video recordings, posters, flyers, records of student organizations, and more. Materials have been donated to the Stanford University Archives for permanent retention, or loaned for selective scanning, and returned to donors. This collection was created as part of the Stanford Alumni Legacy Project (SALP) initiative. SALP focuses on collecting, preserving, and providing long-term access to student materials created by Stanford alumni during their time on the farm. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Stanford Alumni Collection (SC1278). Dept. of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Arrangement Collection materials are described alphabetically in the finding aid by last name of donor. Boxes are listed by accession numbers (ARCH-YYYY-###), which are provided in the finding aid. Alumni class graduation years are indicated as provided. -

Palo Alto Activity Guide

FALL/WINTER 2018 Visitors Guide to the Midpeninsula DISCOVER WHERE TO DINE, SHOP, PLAY OR RELAX Fa r m -to- table A local’s guide to seasonal dining Page 26 DestinationPaloAlto.com TOO MAJOR TOO MINOR JUST RIGHT FOR HOME FOR HOSPITAL FOR STANFORD EXPRESS CARE When an injury or illness needs quick Express Care is attention but not in the Emergency available at two convenient locations: Department, call Stanford Express Care. Stanford Express Care Staffed by doctors, nurses, and physician Palo Alto assistants, Express Care treats children Hoover Pavilion (6+ months) and adults for: 211 Quarry Road, Suite 102 Palo Alto, CA 94304 • Respiratory illnesses • UTIs (urinary tract tel: 650.736.5211 infections) • Cold and flu Stanford Express Care • Stomach pain • Pregnancy tests San Jose River View Apartment Homes • Fever and headache • Flu shots 52 Skytop Street, Suite 10 • Back pain • Throat cultures San Jose, CA 95134 • Cuts and sprains tel: 669.294.8888 Open Everyday Express Care accepts most insurance and is by Appointment Only billed as a primary care, not emergency care, 9:00am–9:00pm appointment. Providing same-day fixes every day, 9:00am to 9:00pm. Spend the evening at THE VOICE Best of MOUNTAIN VIEW 2018 THE THE VOICE Best of VOICE Best of MOUNTAIN MOUNTAIN VIEW VIEW 2016 2017 Castro Street’s Best French and Italian Food 650.968.2300 186 Castro Street, www.lafontainerestaurant.com Mountain View Welcome The Midpeninsula offers something for everyone hether you are visiting for business or pleasure, or W to attend a conference or other event at Stanford University, you will quickly discover the unusual blend of intellect, innovation, culture and natural beauty that makes up Palo Alto and the rest of the Midpeninsula. -

Stanford University Architectural Collection SC1043

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9g5041mg Online items available Guide to the Stanford University Architectural Collection SC1043 compiled by University Archives staff Department of Special Collections and University Archives October 2010 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Note This encoded finding aid is compliant with Stanford EAD Best Practice Guidelines, Version 1.0. Guide to the Stanford University SC1043 1 Architectural Collection SC1043 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Stanford University Architectural Collection creator: Stanford University Identifier/Call Number: SC1043 Physical Description: 2800 item(s) Date (inclusive): 1889-2015 Abstract: The materials consist of architectural drawings of Stanford University buildings and grounds. Conditions Governing Access The materials are open for research use; materials must be requested at least 48 hours in advance of intended use. Audio-visual materials are not available in original format, and must be reformatted to a digital use copy. Scope and Contents The materials consist of architectural drawings of Stanford University buildings and grounds. Arrangement The materials are arranged by building or drawing name. Conditions Governing Use All requests to reproduce, publish, quote from, or otherwise use collection materials must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94304-6064. Consent is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission from the copyright owner. Such permission must be obtained from the copyright owner, heir(s) or assigns. -

Alternatives Open for High-Speed Rail Page 3

Palo 6°Ê888]Ê ÕLiÀÊ£ÊUÊiLÀÕ>ÀÞÊ£Ó]ÊÓä£ä N xäZ Alto Alternatives open for high-speed rail Page 3 www.PaloAltoOnline.com Page 17 Spectrum 12 Title Pages 14 Eating Out 27 Movies 30 Puzzles 52 NArts Talisman sings soulful stories a cappella Page 22 NSports Stanford hosts Cal in Big Splash Page 32 NHome Orchids: extraordinary and elegant Page 37 Perinatal Obstetric Diagnostic Anesthesia Center Packard Center for Stanford Children’s Fetal Health School of Hospital Medicine TOGETHER WHAT DREW US HERE AS DOCTORS, DRAWS US BACK AS PATIENTS. Obstetricians Karen Shin and Mary Parman spend their days caring for pregnant patients and delivering babies. Now that each doctor is pregnant with her first child, the choice of where to deliver is clear: right here where they deliver their patients’ babies, at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital. “At Packard, every specialist you could ever need is available within minutes, around the clock. When you’ve seen how successfully the physicians, staff and nurses work, especially in unpredictable situations, you instinctively www.lpch.org want that level of care for you and your baby.” To learn more about the services we provide to expectant mothers and babies, visit lpch.org Page 2ÊUÊiLÀÕ>ÀÞÊ£Ó]ÊÓä£äÊUÊ*>ÊÌÊ7iiÞ UpfrontLocal news, information and analysis Tunnels still possible in Palo Alto, rail officials say New ‘alternatives analysis’ will evaluate marized their progress on the de- options for high-speed rail on the built along the Caltrain corridor. sign of the controversial system Peninsula, is currently scheduled Spaethling, who is in charge of underground, elevated options for high-speed rail at a hearing in Palo Alto Tuesday for release March 4. -

Stanford University, Publication Services, Word Graphics Photographs

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt8w103850 No online items Guide to the Stanford University, Publication Services, Word Graphics Photographs Processed by Patricia White; machine-readable finding aid created by Patricia White Stanford University. Libraries.Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford, California 2000 Copyright © 2015 The Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. Guide to the Stanford University, PC0089 1 Publication Services, Word Graphics Photographs ... Overview Call Number: PC0089 Creator: Stanford University. Publication Services. Word Graphics. Title: Stanford University, Publication Services, Word Graphics photographs Dates: 1931-1961 Physical Description: 0.75 Linear feet Language(s): The materials are in English. Repository: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford, CA 94305-6064 Email: [email protected] Phone: (650) 725-1022 URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Custodial History Administrative transfer Information about Access None. Ownership & Copyright Property rights reside with the repository. Literary rights reside with the creators of the documents or their heirs. To obtain permission to publish or reproduce, please contact the Public Services Librarian of the Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives. Cite As [Identification of item], Stanford University Publication Services Word Graphics Photographs (PC0089). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archvies, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Separated Materials The following damaged negatives were discarded: 35 mm negatives of a Sterling event 8x10 negative of Dr. Edward Curtis Franklin, red chalk drawing, 1937 8x10 negative of Dr. A. T. Murray and wife (number 466) 4x5 negative of orchestra or band conductor 4x5 negative of construction scene Scope and Content This collection consists largely of photonegatives, with a few photoprints and color transparencies. -

Campus Maps, Stanford University

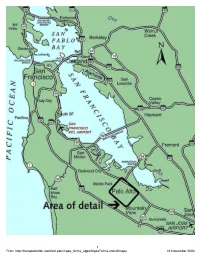

1 From http://transportation.stanford.edu/maps_forms_apps/MapsForms.shtml#maps 14 November 2004 2 From http://transportation.stanford.edu/maps_forms_apps/MapsForms.shtml#maps 14 November 2004 Wilkes SWEET Bashford OLIVE WY Legend STANFORD Nordstrom Stanford B of A Visitor Information Shopping Crate & Barrel Center VINEYARD LANE ARBORETUM RD Palo Alto Medical Foundation UNIVERSITY Andronico’s Bus Pick-up/Drop-off Point Psychiatry Town and Country 770 Bike route to Menlo750 Park Bike Bridge Shopping Center Bus Parking 730 VISITOR 780 Stanford Barn 700 WELCH RD Angel of Arboretum Blood Grief Grove Visitor Parking 800 Center EMBARCADERO RD QUARRY RD INFORMATION 777 To (US 101) Ear HWY 82 EL CAMINO REAL 701 Palo Alto Pedestrian Lane Inst. Lucile 703 Sleep High School MAP 900 Packard Ctr Mausoleum 1000 Children’s Hospital T S El Camino at Stanford Grove SAND 1100HILL RD900 Blake Z Heliport Cactus Wilbur LASUEN ST E O Garden NF RD Clinic Parking Falk A S Struct. 3 Lasuen V T T Stanford West Apartments & Knowledge Beginnings Child Development Center Center S A Grove L D CLARK I HomeTel Welch Plaza U Bike route to WY Stanford A Toyon Foster M Hospital Grove Field Palo Alto/Bryant St. S G C A M P U PASTEUR DRIVE Emergency BLAKE WILBUR DR DRIVE G.A. Richards Parking Press Box B Struct. 4 Old NELSON RD Maloney Stanford Athletics Lucas Clinic Anatomy LOMITA DR Galvez Ticket Field Sand Hill Fields Ctr./MSLS Field Cantor Center Office SAM MACDONALD MALL QUARRY EXTENSION for PALM DRIVE CHURCHHILL AVE Parking Park & A Health Res. -

2010-11 Stanford University Parking and Circulation

*$#.)(5& +,"--.-/("# %2 $(+%$$7(2% # $ (" 2 - " ! /4.-2"()* % & & 1 " - * * $ 1 & 6 /%$$-!112("# / 8&1%$-+$()* ) & (" * - $%( " 4-.#$%).*'(2% 1 %16&$("# & 84&*1-()* ' () 0.22&$8.$&2(%2 " * 1 8%$01-*()* 5 81%$)*("# + $ ,"!*,1%-$("# ) +1%.--$(&- 0$&#.&&$("# ,"%7$%("# "%61%(%2 +1&&$/$("# +1%-$&&(%2 21!-.-/(&- "&.+$(&- ,"%#"%2("# 8&1%$-+$(&- Downtown 1 5"%*%.2/$("# ,10$%("# 5%"2 $#$%$**("# )"-*"(+%4:("# 0"&&$*(+* 5"4&)$-(&- Palo Alto /.&0"-()* +"06%.2/$("# 5"%7.-)1-("# % 7.5&.-/()* !.-2)1%(!' 2 $&(+"0.-1(%$"& &'**1-("# '"&$(%2 7 0"'(6%1!-("# $ +")*&$(!' $ + % 1 ,$%01)"(!' ! 5.-$()* + "22.)1-("# 5 !.&)1-()* )"91-(!' !$%*,("# $ 6'%1-()* !.-2)1%(2% % 5%.-+$*1-(%2 () ,"%%.$*()* %1)$8.$&2(!' ! 4-.#$%).*'(("# * " "%61%(%2 & 0 Palo Alto !"#$%&$'()* &$ 0.22&$("# . " *+ Transit &.-+1&-("# 2 , Center ,157.-)("# % $& & ,"0.&*1-("# ) 5$"%(&- (& )+1**()* "- MacArthur - (0 +&".%$ " Park * 5 7.-/)&$'("# $1 & 0 ,1 (2 )"-2(,.&&(%2 Stanford 6%'"-*()* 6 % " 51&.*:$%(2% " Shopping *"))1()* %* ' , ,$%01)"(!' ! % Center 4%6"-(&- .& ) 2 &# * )"-(0"*$1(2%11 %"01-"()* 0$&#.&&$("# .$ 2 & ! & $ - 2% % , $ 4 ;4"%%'(%2 ) " $0$%)1-()* 7 & $ )"-*"(%.*"("# Sheraton 7$&&1//("# *, Hotel 2 +1**1-()* 1 2 3 ' 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 % " COWPER William R. ! 6 WAVERLEY ST #."(54$6&1 Westin ,./,()* $ 6 Hotel Hewlett Serra )$%%"(0"&& ) Downtown Hoover Pavilion $06"%+"2$%1(%2 * EVERETT Applied Teaching EL CAMINO REAL BRYANT ST Grove $%( ,16"%*()* HIGH ST Palo Alto Classic Residence (see INSET 1 Arboretum !$&&)("#$ 1%+,"%2(((&- Center A L-1 Childen's ,10$%("#Physics Center -

2017 Stanford Reunion Homecoming Guide

OCTOBER 12–15, 2017 2017 Stanford Reunion Homecoming Guide Your classmates. Your memories. Yo u r f r i e n d s . Your sandstone. Your dormmates. Your spot. Yo u r y e a r. Yo u r m i n d . Yo u r r e u n i o n . OCTOBER 12–15, 2017 Contents Welcome back to the Farm, friend! Here’s your guide to all Reunion Homecoming events and activities. For more details, simply turn the page and dive in! EVENTS & ACTIVITIES* HOW TO GET AROUND YOUR THURSDAY ............................................................................... 2 VENUE MAP ........................................................................................... 10 YOUR FRIDAY .........................................................................................6 CLASS TENT MAP ............................................................................. 22 YOUR SATURDAY ................................See Saturday insert KEY REUNION INFO ........................................................................ 21 YOUR SUNDAY .....................................................................................17 CLASSES WITHOUT QUIZZES & TOURS ......................19 EXPLORE CAMPUS ......................................................................... 20 YOUR CLASS EVENTS .............See class events insert *Want to know where your events are located? Letters/numbers in parentheses next to event listings correspond to coordinates on the venue map (pages 10–11 and on the folder). Share your favorite EVENT KEY #StanfordReunion moments MAIN EVENTS ....................................................... -

Visitor Parking & Information Map / Bus Loading & Parking

BUILDINGS RESIDENCES BUILDING NAME GRID BUILDING NAME GRID BUILDING NAME GRID RESIDENCE GRID Acacia F-5 Escondido Elementary School J/K-13/14 Nora Suppes Hall F-4 565 Mayfield K-8 Advanced Medicine Ctr. (Cancer Center) C-5 Escondido Village Community Center J-13/14 Oak F-5 680 Lomita K-7 Allen Center for Integrated Systems (CIS) F-6 Escondido Village Offices J-14 Observatory L-3 BOB (Moore South) J-8 Anatomy E-4 Facilities Operations Bldgs. F/G-13/14 Old Chemistry Bldg. F-7 Branner Hall H/I-11 Anatomy, Old D-7/8 Faculty Club I-7 Old Union (Student Services) H/I-8 Casa Italiana (Moore North) J-8 Applied Physics Bldg. F/G-6 Fairchild Center E-6 Organic Chemistry Bldg. E-7 Chi Theta Chi J-10 Arboretum Children's Center A-9 Falk Center C/D-6 Owen House J-9 Columbae J-8 Arguello, 425-429 H-10 Fire Station G-13 Packard Children's Hospital C-5 Cowell Cluster Houses: Delta Delta Delta (DDD), J/K-11 Arrillaga Alumni Center, Frances F-11 Fire Truck House I-7 Packard Hospital Auxiliary F-1 Kappa Alpha Theta (KAQ), Terra, Pi Beta Phi (PBF), ZAP Arrillaga Family Recreation Center F-11 Forsythe Hall G-5 Palo Alto Train Station & Transit Ctr. N.of A-8 Crothers Hall, Crothers Memorial Hall H-10 Arrillaga Family Sports Center F-11/12 Frost Amphitheater, Laurence E/F-9/10 Parking & Transportation Services G-12/13 Durand L-9 Art Gallery and Bookshop G-9 Galvez Module H-9 Parking Structure 1 D/E-7 Enchanted Broccoli Forest K-6 Artist’s Studio K-3 Gates Computer Sciences Bldg. -

Stanford University, Press, Photographs

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt7z09s4v3 No online items Guide to the Stanford University, Press, Photographs Daniel Hartwig Stanford University. Libraries.Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford, California October 2010 Copyright © 2015 The Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. Note This encoded finding aid is compliant with Stanford EAD Best Practice Guidelines, Version 1.0. Guide to the Stanford University, PC0093 1 Press, Photographs Overview Call Number: PC0093 Creator: Stanford University. Press. Title: Stanford University, Press, photographs Dates: 1924-1976 Bulk Dates: 1924-1945 Physical Description: 2.25 Linear feet Summary: Collection includes photographs, 1936-1945, and one scrapbook, 1924-1976. Subjects of the photographs are the Stanford University Press and staff; Stanford University buildings, students, and faculty/staff; and San Francisco's skyline and bay bridge. Of note among the Stanford photographs are scenes of army training during World War II, the 1942 commencement, the Flying Indians (student flying club), class and laboratory scenes, and a radio workshop ca. 1940. Individuals include John Borsdamm, Will Friend, Herbert Hoover, Marchmont Schwartz, Clark Shaughnessy, Graham Stuart, and Ray Lyman Wilbur. The album pertains largely to staff in the press bindery and includes photographs, clippings, letters, notes, humorous pencil sketches, and poems, mostly by Carlton L. Whitten. Language(s): The materials are in English. Repository: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford, CA 94305-6064 Email: [email protected] Phone: (650) 725-1022 URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Administrative transfer from the Stanford University Press, 2000.