Azerbaijani Government Crackdown in Ganja

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Care Systems in Transition

Health Care Systems in Transition Written by John Holley Oktay Akhundov Ellen Nolte Edited by Ellen Nolte Laura MacLehose Martin McKee Azerbaijan 2004 The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies is a partnership between the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, the governments of Belgium, Finland, Greece, Norway, Spain and Sweden, the European Investment Bank, the Open Society Institute, the World Bank, the London School of Economics and Political Science, and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Keywords: DELIVERY OF HEALTH CARE EVALUATION STUDIES FINANCING, HEALTH HEALTH CARE REFORM HEALTH SYSTEM PLANS – organization and administration AZERBAIJAN © WHO Regional Office for Europe on behalf of European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2004 This document may be freely reviewed or abstracted, but not for commercial purposes. For rights of reproduction, in part or in whole, application should b e made to the Secretariat of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Scherfigsvej 8, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark. The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies welcomes such applications. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies or its participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The names of countries or areas used in this document are those which were obtained at the time the original language edition of the document was prepared. -

The Effectiveness of Police Accountability Mechanisms and Programs What Works and the Way Ahead

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF POLICE ACCOUNTABILITY MECHANISMS AND PROGRAMS WHAT WORKS AND THE WAY AHEAD August 2020 DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. THE EFFECTIVENESS OF POLICE ACCOUNTABILITY MECHANISMS AND PROGRAMS WHAT WORKS AND THE WAY AHEAD Contract No. AID-OAA-I-13-00032, Task Order No. AID-OAA-TO-14-00041 Cover photo (top left): An Egyptian anti-Mubarak protestor holds up scales of justice in front of riot police. (Credit: Khaled Desouki, Agence France-Presse) Cover photo (top right): Royal Malaysian Police deputy inspector-general looks on as Selangor state police chief points to a journalist during a press conference. (Credit: Mohd Rasfan, Agence France-Presse) Cover photo (bottom left): Indian traffic police officer poses with a body-worn video camera. (Credit: Sam Panthaky, Agence France-Presse) Cover photo (bottom right): Indonesian anti-riot police take position to disperse a mob during an overnight-violent demonstration. (Credit: Bay Ismoyo, Agence France-Presse) DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. ii Acronyms ..................................................................................................................................ii -

United Nations Code for Trade and Transport Locations (UN/LOCODE) for Azerbaijan

United Nations Code for Trade and Transport Locations (UN/LOCODE) for Azerbaijan N.B. To check the official, current database of UN/LOCODEs see: https://www.unece.org/cefact/locode/service/location.html UN/LOCODE Location Name State Functionality Status Coordinatesi AZ ABN Agcabadi AGC Road terminal; Recognised location 4003N 04727E AZ AST Astara Multimodal function, ICD etc.; Recognised location 3827N 04852E AZ BAK Baku Port; Airport; Postal exchange office; Code adopted by IATA or ECLAC AZ DAM Dalimammadli GOR Road terminal; Recognised location 4041N 04634E AZ DJU Djulfa Rail terminal; Code adopted by IATA or ECLAC AZ GAN Ganja Multimodal function, ICD etc.; Recognised location 4040N 04621E AZ GYD Heydar Aliyev BA Airport; Recognised location 4028N 05002E International Apt. AZ IMI Imisli Road terminal; Recognised location 3952N 04803E AZ KAZ Qazax QAZ Rail terminal; Road terminal; Recognised location 4106N 04521E AZ KBD Kirovabad GA Rail terminal; Road terminal; Request under consideration AZ KHA Khanlar Road terminal; Recognised location 4020N 04949E AZ KMZ Khachmaz XAC Port; Multimodal function, ICD etc.; Recognised location 4159N 04735E AZ KVD Gyandzha Airport; Code adopted by IATA or ECLAC AZ LAN Lankaran Road terminal; Recognised location 3845N 04851E AZ MGC Mingechaur Road terminal; Recognised location 4045N 04703E AZ NAJ Naxcivan Road terminal; Recognised location 3912N 04514E AZ NK7 Nakhchivan Rail terminal; Recognised location 3912N 04524E AZ QDG Qaradag Port; Rail terminal; Road terminal; Recognised location 4015N 04936E AZ -

Republic of Azerbaijan Country Report

NCSEJ Country Report Email: [email protected] Website: NCSEJ.org Azerbaijan Zaqatala Quba Shaki Shabran Siazan Shamkir Mingachevir Ganja Yevlakh Sumqayit Hovsan Barda Baku Agjabedi Imishli Sabirabad Shirvan Khankendi Salyan Jalilabad Nakhchivan Lankaran m o c 60 km . s p a m - d 40 mi © 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 3 Azerbaijan is secular republic. Approximately 93% of the country’s inhabitants have an Islamic background. About 5% are Christian. The remainder of the population belongs to various religions. Around 30,000 Jews live in Azerbaijan. History ........................................................................................................................................... 4 The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, also known as Azerbaijan People's Republic or Caucasus Azerbaijan in diplomatic documents, was the third democratic republic in the Turkic world and Muslim world, after the Crimean People's Republic and Idel-Ural Republic. Found in May 28, 1918 by Mahammad Amin Rasulzadeh. Ganja city was the Capital of Azerbaijan People’s Republic. Domestic Affairs ............................................................................................................................. 5 Azerbaijan is a constitutional republic with executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The executive branch dominates and there is no independent judiciary. The President and the National Assembly are elected -

River Basin Management Development in Kura Upstream Mingachevir Dam River Basin District in Azerbaijan

European Union Water Initiative Plus for Eastern Partnership Countries (EUWI+): Results 2 and 3 ENI/2016/372-403 RIVER BASIN MANAGEMENT DEVELOPMENT IN KURA UPSTREAM MINGACHEVIR DAM RIVER BASIN DISTRICT IN AZERBAIJAN PART 1 - CHARACTERISATION PHASE THEMATIC SUMMARY EUWI-EAST-AZ-03 January 2019 EUWI+: Thematic summary Kura Upstream of Mingachevir Reservoir River basin Produced by SADIG LLC Authors: Vafadar Ismayilov, Fuad Mammadov, Anar Nuriyev,Farda Imanov, Farid Garayev Supervision Yannick Pochon Date 12.01.2019 Version Draft Acknowledgements: NEMD MENR, NHMD MENR, NGES MENR, Amelioration JSC, Azersu OSC, WRSA MOES Produced for: EUWI+ Financed by: European Union – Co-financed by Austria/France DISCLAMER: The views expressed in this document reflects the view of the authors and the consortium implementing the project and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. Page | 2 EUWI+: Thematic summary Kura Upstream of Mingachevir Reservoir River basin TABLE OF CONTENT 1. CHARACTERIZATION OF THE RIVER BASIN DISTRICT ..................................................................... 4 1.1 Natural Conditions in the River Basin District (RBD) ......................................................................... 4 1.2 Hydrological & geohydrological characteristics of the RBD ............................................................... 5 1.3 Driving forces ...................................................................................................................................... 6 1.4 The river basin in -

The World Factbook Middle East :: Azerbaijan Introduction

The World Factbook Middle East :: Azerbaijan Introduction :: Azerbaijan Background: Azerbaijan - a nation with a majority-Turkic and majority-Shia Muslim population - was briefly independent (from 1918 to 1920) following the collapse of the Russian Empire; it was subsequently incorporated into the Soviet Union for seven decades. Azerbaijan has yet to resolve its conflict with Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh, a primarily Armenian-populated region that Moscow recognized in 1923 as an autonomous republic within Soviet Azerbaijan after Armenia and Azerbaijan disputed the territory's status. Armenia and Azerbaijan began fighting over the area in 1988; the struggle escalated after both countries attained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. By May 1994, when a cease-fire took hold, ethnic Armenian forces held not only Nagorno-Karabakh but also seven surrounding provinces in the territory of Azerbaijan. The OSCE Minsk Group, co-chaired by the United States, France, and Russia, is the framework established to mediate a peaceful resolution of the conflict. Corruption in the country is widespread, and the government, which eliminated presidential term limits in a 2009 referendum, has been accused of authoritarianism. Although the poverty rate has been reduced and infrastructure investment has increased substantially in recent years due to revenue from oil and gas production, reforms have not adequately addressed weaknesses in most government institutions, particularly in the education and health sectors. Geography :: Azerbaijan Location: Southwestern -

Republic of Azerbaijan Ministry of Transport Road Transport Services Department

Supplementary Appendix C Republic of Azerbaijan Ministry of Transport Road Transport Services Department EAST–WEST HIGHWAY IMPROVEMENT PROJECT RESETTLEMENT PLAN June 2005 THIS IS NOT AN ADB BOARD APPROVED DOCUMENT To: Head of the Road Maintenance Agency of Gornboy/Yevlax/Ganja/Xanlar The draft Resettlement Plan for the Rehabilitation of the East-West Corridor Road of the Azerbaijan Republic has been prepared by the Road Transport Service Department in accordance with the Azerbaijan law and ADB guidelines on resettlement. The Resettlement Plan covers land acquisition and other resettlement aspects for the rehabilitation of the road segments from Yevlax to Ganja and from Gazax to the border with Georgia. The draft Resettlement Plan is based on the studies of social and economic conditions of businesses, ordinary people and families that have been affected by the above mentioned road rehabilitation project as well as on the consultations with local authorities. The impact shown in the Resettlement Plan reflects the results of the Technical Assistance provided by the ADB. The draft Resettlement Plan will be upgraded and completely finalized in 2006 . This draft Resettlement Plan has been approved by RTSD and ADB and may be disclosed to all affected communities and people. We authorize your agency to disclose the Resettlement Plan to all concerned parties as necessary. Attachment: draft resettlement Plan – 54 pages Head of the Road Maintenance Division V. Hajiyev CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND 1.1. Outline of the Project 1.2 Status of the Road Reserve 2. SOCIOECONOMIC CONDITIONS IN THE PROJECT AREA 2.1 Project Impact Areas 2.2 Social Profile of the Project Areas 3. -

Out of Control Special Seattle’S Flawed Response to Protests Report Against the World Trade Organization

A Out of Control Special Seattle’s Flawed Response to Protests Report Against the World Trade Organization June 2000 American Civil Liberties Union of Washington 705 Second Ave., Suite 300 Seattle, WA 98104-1799 (206) 624-2184 www.aclu-wa.org Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary.......................................................................................... 5 Recommendations ............................................................................................. 11 I. BY CREATING A “NO PROTEST ZONE,” THE CITY NEEDLESSLY VIOLATED RIGHTS TO FREEDOM OF SPEECH AND ASSEMBLY Setting the Stage: Failure to Protect Delegates’ Rights to Assembly.......................... 15 Proper Security Measures: How to Protect Everyone’s Rights ................................... 16 The “No Protest Zone:” A Militarized Zone That Suspended Civil Liberties .......... 18 “No Protest Zone” Not Designed for Security .............................................................. 22 “No Protest Zone” Not Needed to Protect Property.................................................... 22 Ratification Process for Emergency Orders Flawed ..................................................... 23 Failure to Plan.................................................................................................................... 24 Lack of Information Not a Problem ............................................................................... -

Country Profile – Azerbaijan

Country profile – Azerbaijan Version 2008 Recommended citation: FAO. 2008. AQUASTAT Country Profile – Azerbaijan. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rome, Italy The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licencerequest or addressed to [email protected]. FAO information products are available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/ publications) and can be purchased through [email protected]. -

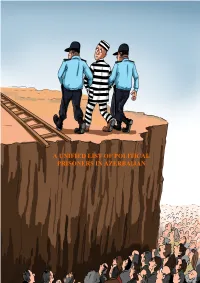

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested -

Water Cannon (Issue 2.0)

Medical implications of the use of vehicle mounted water cannon (Issue 2.0) <redacted> Dstl/TR08591 Issue 2 Dstl Porton Down February 2004 Salisbury Wilts SP4 0JQ © Crown copyright 2004 Dstl Release conditions This document has been prepared for DOMILL under Northern Ireland Office funding and, unless indicated, may be used and circulated in accordance with the conditions of the Order under which it was supplied. It may not be used or copied for any non-Governmental or commercial purpose without the written agreement of Dstl. © Crown Copyright, 2004 Defence Science and Technology Laboratory UK Approval for wider use or release must be sought from: Intellectual Property Department Defence Science and Technology Laboratory, Porton Down, Salisbury, Wiltshire SP4 OJQ Authorisation (Complete as applicable) Name Signature Group Leader <redacted> Date Project Manager <redacted> Date Technical Reviewer <redacted> Date Executive summary The Northern Ireland Office and the Home Office have requested an independent opinion on the medical implications of the use of water cannon in public-order incidents. The DSAC Sub- committee on the Medical Implications of Less Lethal weapons (DOMILL) has been requested to provide this opinion. On behalf of DOMILL, Dstl Biomedical Sciences has undertaken a review of published information from a wide range of sources on the reported incidence world-wide of injuries from jets of water from water cannon. This is believed to be the first such review despite extensive use of water cannon by police and other agencies in many other countries. There were no fatalities reported in the literature that were directly attributable to the impact of the jet in public order situations. -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Report No: ISR5276 Implementation Status & Results Azerbaijan Second National Water Supply and Sanitation Project (P109961) Operation Name: Second National Water Supply and Sanitation Project Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 8 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 05-Jul-2011 (P109961) Public Disclosure Authorized Country: Azerbaijan Approval FY: 2008 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: EUROPE AND CENTRAL ASIA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): State Amelioration and Water Management Agency of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic (SAWMA), State Amelioration and Water Management Company Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 27-May-2008 Original Closing Date 28-Feb-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date Last Archived ISR Date 05-Jul-2011 Effectiveness Date 13-Jul-2009 Revised Closing Date 28-Feb-2013 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) To improve the availability, quality, reliability and sustainability of water supply and sanitation (WSS) services in selected regional (rayon) centers in Azerbaijan. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Component A: Rayon Investments 392.00 Component B: Institutional Modernization 15.80 Component C: Project Implementation and Management 1.60 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Moderately Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Moderately Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Public Disclosure Authorized Overall Risk Rating Implementation Status Overview This information is based on recent implementation support mission led by Manuel Marino and composed of Hadji Huseynov, Deepal Fernando, Gulana Hajiyeva and Norpulat Daniyarov and carried out through October 31- November 4, 2011.