Re-Looking the Role of CV Kunjuraman in the Social Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extrimist Movement in Kerala During the Struggle for Responsible Government

Vol. 5 No. 4 April 2018 ISSN: 2321-788X UGC Approval No: 43960 Impact Factor: 3.025 EXTRIMIST MOVEMENT IN KERALA DURING THE STRUGGLE FOR RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT Article Particulars: Received: 13.03.2018 Accepted: 31.03.2018 Published: 28.04.2018 R.T. ANJANA Research Scholar of History, University of Kerala, India Abstract Modern Travancore witnessed strong protests for civic amenities and representation in legislatures through the Civic Rights movement and Abstention movement during 1920s and early part of 1930s. Government was forced to concede reforms of far reaching nature by which representations were given to many communities in the election of 1937 and for recruitment a public service commission was constituted. But the 1937 election and the constitution of the Public Service Commission did not solve the question of adequate representation. A new struggle was started for the attainment of responsible government in Travancore which was even though led in peaceful means in the beginning, assumed extremist nature with the involvement of youthful section of the society. The participants of the struggle from the beginning to end directed their energies against a single individual, the Travancore Dewan Sir. C. P. Ramaswamy Iyer who has been considered as an autocrat and a blood thirsty tyrant On the other side the policies of the Dewan intensified the issues rather than solving it. His policy was dividing and rule, using the internal social divisions existed in Travancore to his own advantage. Keywords: civic amenities, Civic Rights, Public Service Commission, Travancore, Civil Liberties Union, State Congress In Travancore the demand for responsible government was not a new development. -

The Socio-Economic Underpinnings of Vaikam Sathyagraha in Travancore

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Colonialism, Social Reform and Social Change : The Socio-Economic underpinnings of Vaikam Sathyagraha in Travancore Dr. Subhash. S Asst. Professor Department of History Government College , Nedumangadu Thiruvanathapuram, Kerala. Abstract Vaikam Sathyagraha was a notable historical event in the history of Travancore. It was a part of antiuntouchability agitation initiated by Indian National Congress in 1924. In Travancore the Sathyagraha was led by T.K.Madhavan. Various historical factors influenced the Sathyagraha. The social structure of Travancore was organised on the basis of cast prejudices and obnoxious caste practices. The feudal economic system emerged in the medieval period was the base of such a society. The colonial penetration and the expansion of capitalism destroyed feudalism in Travancore. The change in the structure of economy naturally changed the social structure. It was in this context so many social and political movements emerged in Travancore. One of the most important social movements was Vaikam Sathyagraha. The British introduced free trade and plantations in Travancore by the second half of nineteenth century. Though it helped the British Government to exploit the economy of Travancore, it gave employment opportunity to so many people who belonged to Avarna caste. More over lower castes like the Ezhavas,Shannars etc. economically empowered through trade and commerce during this period. These economically empowered people were denied of basic rights like education, mobility, employment in public service etc. So they started social movements. A number of social movements emerged in Travancore in the nineteenth century and the first half of twentieth century. -

UNIVERSITY of KERALA No.Ad.H/30652/2017/1 N O T I F I C a T I O N Applications Are Invited from Qualified Candidates for Appoint

UNIVERSITY OF KERALA No.Ad.H/30652/2017/1 N O T I F I C A T I O N Applications are invited from qualified candidates for appointment to the posts of Assistant Professor in the following Teaching Departments of the University in the scale of pay of Rs. 15600- 39100 (AGP Rs.6000/-) (Pre revised). Appointments to the posts will be made in accordance with Section (6) Sub Section (2) of Chapter II of the Kerala University Act,1974, UGC Regulations 2010 and amendments made thereon. The turn of appointment as per the principles of rotation is given against each post. Sl. No. Department No. of Turn vacancies 1. Department of Aquatic Biology &Fisheries 1 Muslim 2. Department of Arabic 1 Open 3. Department of Biochemistry 2 OBC Open 4. Department of Commerce 1 Open 5. Department of Communication & Journalism 1 Open 6. Department of Geology 1 SC 7. Department of German 2 Muslim Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 8. Department of Hindi 1 Open 9. Department of Islamic Studies 1 SIUC Nadar 10. Department of Law 1 Ezhava/Billava/Thiyya SC 11. Department of Library & Information Science 3 Ezhava/Billava/Thiyya Hearing Impaired 12. Department of Linguistics 1 Open 13. Department of Malayalam 1 Open 14. Department of Mathematics 3 Ezhava/Billava/Thiyya Open Open 15. Department of Philosophy 1 Open 16. Department of Physics 1 Ezhava/Billava/Thiyya 17. Department of Political Science 2 Open Open 18. Department of Psychology 1 OBC 19. Department of Russian 1 Open 20. Department of Sanskrit 2 Muslim Viswakarma 21. Department of Statistics 2 SC Open 22. -

![Temple Entry Movement for Depressed Class in South Travancore [Kanyakumari] Prathika](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3132/temple-entry-movement-for-depressed-class-in-south-travancore-kanyakumari-prathika-703132.webp)

Temple Entry Movement for Depressed Class in South Travancore [Kanyakumari] Prathika

Prathika. S al. International Journal of Institutional & Industrial Research ISSN: 2456-1274, Vol. 3, Issue 1, Jan-April 2018, pp.4-7 Temple Entry Movement for Depressed Class in South Travancore [Kanyakumari] Prathika. S Ph.D. Research Scholar, Department of History and Research Centre, S.T. Hindu College, Nagercoil 629002. Abstract: The four Tamil speaking taluks of Kanyakumari Dist viz;Agasteeswaram, Thovalai, Kalkulam and Vilavancode consisted the erst while South Tavancore. Among the various religions, Hinduism is the predominant one constituting about two third of the total population. The important Hindu temples found in Kanyakumari District are at Kanyakumari, Suchindrum, Kumarakoil,Nagercoil, Thiruvattar and Padmanabhapuram. The village God like Madan,Isakki, Sasta are worshipped by the Hindus. The people of South Travancore segregated and lived on the basis of caste. The whole population could be classified as Avarnas or Caste Hindus and Savarnas or non-caste people. The Savarnas such as Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Sudras who enjoyed special powers and privileges of wealth constituted the higher castes. The Avarnas viz the Nadars, Ezhavas, Mukkuvas, Sambavars, Pulayas and numerous hill tribes were considered as the polluting castes and were looked down on and had to perform various services for the Savarnas . Avarnas were not allowed in public places, temples, and the temple roads also. Low caste people or Avarnas were considered as untouchable people. Untouchability, one of the major debilities prevailed among the lower order of the society in South Travancore caused an indelible impact on the society. Keywords: Temple Entry Movement, Depressed Class, Kanyakumari reformers against that oppressive activities. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

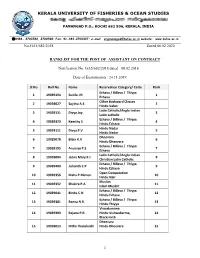

Ranklist for the Post of Assistant on Contract

KERALA UNIVERSITY OF FISHERIES & OCEAN STUDIES PANANGAD P.O., KOCHI 682 506, KERALA, INDIA 0484- 2703782, 2700598; Fax: 91-484-2700337; e-mail: [email protected] website: www.kufos.ac.in No.GA5/682/2018 Dated,06.02.2020 RANKLIST FOR THE POST OF ASSISTANT ON CONTRACT Notification No. GA5/682/2018 dated 08.02.2018 Date of Examination : 24.11.2019 Sl No Roll No Name Reservation Category/ Caste Rank Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 1 19039194 Sunila .M 1 Ezhava Other Backward Classes 2 19039027 Sajitha A.S 2 Hindu Valan Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 3 19039131 Divya Joy 3 Latin catholic Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 4 19039323 Keerthy S 4 Hindu Ezhava Hindu Nadar 5 19039111 Divya P.V 5 Hindu Nadar Dheevara 6 19039078 Bibin K.V 6 Hindu Dheevara Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 7 19039195 Anusree P.S 7 Ezhava Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 8 19039084 Jeena Mary K J 8 Christian Latin Catholic Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 9 19039403 Jishanth C.P 9 Hindu Ezhava Open Competetion 10 19039356 Nisha P.Menon 10 Hindu Nair Muslim 11 19039352 Shakira P.A. 11 Islam Muslim Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 12 19039041 Bindu.C.N 12 HIndu Ezhava Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 13 19039381 Beena N.K. 13 Hindu Thiyya Viswakarama 14 19039383 Rejana P.R. Hindu Vishwakarma, 14 Blacksmith Dheevara 15 19039013 Hitha Thanckachi Hindu Dheevara 15 1 16 Amrutha Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 16 19039336 Sundaram Hindu Ezhava Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 17 19039114 Mary Ashritha 17 Latin Catholic Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 18 19039120 Basil Antony K.J 18 Latin Catholic Dheevara 19 19039166 Thushara M.V 19 Deevara Sreelakshmi K Open Competetion 20 19039329 20 Nair Nair Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 21 19039373 Dileep P.R. -

FATHIMA MEMORIAL TRAINING COLLEGE, PALLIMUKKU, KOLLAM - 10 B.Ed 2019-2021 (English / General List)

FATHIMA MEMORIAL TRAINING COLLEGE, PALLIMUKKU, KOLLAM - 10 B.Ed 2019-2021 (English / General List) Sl.No Name Community Index Marks Rank Remarks 1 SHERINA S Muslim 855 1 Allotted 2 ANJALI G R General 827 2 Allotted 3 REJI R LC 815 3 Allotted 4 ARDHANA T A Ezhava 807 4 Allotted 5 KRISHNAJA KJ General 807 5 Allotted 6 ANN PAUL LC 800 6 Ch-1 7 ANEETA DAS LC 799 7 Ch-2 8 ANAGHA G General 797 8 Ch-3 9 SANAYA H NAZAR Muslim 795 9 Ch-4 10 RESHMA MOHAN General 793 10 Ch-5 11 PAVITHRA PRASAD General 790 11 Ch-6 12 SETHULEKSHMI R S General 783 12 Ch-7 13 ASWATHY S KUMAR General 777 13 Ch-8 14 SNEHA MARY ABRAHAM General 772 14 Ch-9 15 MEERA M General 771 15 Ch-10 16 ARCHA T S General 771 16 Ch-11 17 LEKSHMI A General 770 17 Ch-12 18 SARANYA KRISHNAN S General 770 18 Ch-13 19 AYISHA A Muslim 765 19 Ch-14 20 AGNES A LC 761 20 Ch-15 21 ARCHANA ANIL General 758 21 Ch-16 22 ANJALI ANAND OBH 757 22 Ch-17 23 FATHIMA S Muslim 757 23 Ch-18 24 VAISHNAVI R K General 756 24 Ch-19 25 DEVI PRAKASH General 754 25 Ch-20 26 ARDRA H S Ezhava 753 26 Ch-21 27 NISHA FRANK F LC 750 27 Ch-22 28 SWATHI KRISHNA L General 747 28 Ch-23 29 DHANALEKSHMI P General 747 29 Ch-24 30 SUMAYYA SHERIEF Muslim 742 30 Ch-25 31 STEFFY PETER LC 737 31 Ch-26 32 AJMA SUHARA Muslim 734 32 Ch-27 33 NADIYA S NOUSHAD Muslim 730 33 Ch-28 34 SARAH PAUL LC 729 34 Ch-29 35 MITHA MOHAN L Ezhava 725 35 Ch-30 36 SELIN SAM General 721 36 Ch-31 37 SNEHA M R Ezhava 717 37 Ch-32 38 AKSHARA U S General 712 38 Ch-33 39 APSARA RANI M General 710 39 Ch-34 40 THASLEENA SHAJAHAN Muslim 704 40 Ch-35 41 MAHIMADEVI S Ezhava 703 41 Ch-36 Important: Complaints related to Index marks & reservation claims will not be accepted under any circumstances, after the stipulated time. -

Impact of Vaikom and Suchidram Satyagrahas in Travancore- an Historical Overview

IMPACT OF VAIKOM AND SUCHIDRAM SATYAGRAHAS IN TRAVANCORE- AN HISTORICAL OVERVIEW Dr. PRAVEEN. O.K Assistant professor, Department of History, SREE KERALA VARMA COLLE, THRISSUR, KERALA, INDIA. ABSTRACT The chief social evil in Travancore, as elsewhere in India, was caste. Though the traditional caste system was not in vogue in Travancore, the Brahmins held the highest place in society. And owners of all land in the country they depended upon the Nairs for the proper management of of the land. The Nairs grew into a warrior class protecting the interests of the Brahmins to form the upper class. The Ezhavas or Tiyas, the Nadars, the pulayas and the parayas were the low caste. These low castes were subjected to glaring disabilities on account of the peculiar social customs which were very strictly followed in Travancore. The treatment which the untouchables received at the hands of the caste Hindus from time immemorial was unsympathetic and even inhuman. Broadly speaking the people of Travancore divided into Avarnas and Savarnas. The avarnas were low castes such as the Adidravidians, Alvans, Aryans, Baratars, Chakaravars, Ezhavas, Kaniyans, Kuravans, Nadars, panas, pulayas, parayas, velan, vedann etc. KEY WORDS: TRAVANCORE, SATYAGRAHA, TEMPLE, VAIKOM SATYAGRHA, SUCHIDRAM SATYAGRHA, TEMPLE ENTRY PROCLAMATION INTRODUCTION They were strictly prohibited from entering into the temples and using public wells, tanks and chatrams (rest houses). Equal opportunity of education and employment was denied to the Avarnas. Unapprochability was also very severe in Travancore. Francis Day says that, Ilava (Ezhava) must keep 36 paces from Brahmin and 12 from a Nayar while a Kaniyan would pollute a Nambudiri Brahmin at 24 ft., 96 paces as the4 distance for a Pulayan from Nair. -

History in Competitive Exams

HISCC01 History in Competitive Exam No. of Contact Hours: 30 Course Objectives: This course is designed to create awareness about competitive exams among the students and to equip them to achieve their proper carrier. As a part of this, the students are able to understand the basic information about history. Course Outcomes: After completing the course, students are able to face competitive exams conducted by KPSC and UPSC. Module 1 Socio-Religious reform Movements • SNDP Yogam, Nair Service Society, Yogakshema Sabha, Sadhu Jana Paripalana Sangham, Vaala Samudaya Parishkarani Sabha, Samathwa Samajam, Islam Dharma Paripalana Sangham, Prathyaksha Raksha Daiva Sabha, Sahodara Prasthanam etc. Hours: 04 Module 2 Struggles and Social Revolts • Upper cloth revolts.Channar agitation, Vaikom Sathyagraha, Guruvayoor Sathyagraha, Paliyam Sathyagraha. Kuttamkulam Sathyagraha, Temple Entry Proclamation, Temple Entry Act .Malyalee Memorial, Ezhava Memorial etc. Malabar riots, Civil Disobedience Movement, Abstention movement etc. Hours: 04 Module 3 ROLE OF PRESS IN RENAISSANCE • Malayalee, Swadeshabhimani, Vivekodayam, Mithavadi, Swaraj, Malayala Manorama, Bhashaposhini, Mathnubhoomi, Kerala Kaumudi, Samadarsi, Kesari, AI -Ameen, Prabhatham, Yukthivadi, etc Hours: 04 Module 4 AWAKENING THROUGH LITERATURE • Novel, Drama, Poetry, Purogamana Sahithya Prasthanam, Nataka Prashtanam, Library movement etc • Women and social change-Parvathi Nenmenimangalam, Arya Pallam, A V Kuttimalu Amma, Lalitha Prabhu.Akkamma Cheriyan, Anna Chandi, Lalithambika Antharjanam andothers Hours: 04 Module 5 LEADERS OF RENAISSANCE • Thycaud Ayya Vaikundar, Sree Narayana Guru, Ayyan Kali.Chattampi Swamikal, Brahmananda Sivayogi, Vagbhadananda, Poikayil Yohannan(Kumara Guru) Dr Palpu, Palakkunnath Abraham Malpan, Mampuram Thangal, Sahodaran Ayyappan, Pandit K P Karuppan, Pampadi John Joseph, Mannathu Padmanabhan, V T Bhattathirippad, Vakkom Abdul Khadar Maulavi, Makthi Thangal, Blessed Elias Kuriakose Chaavra, Barrister G P Pillai, TK Madhavan, Moorkoth Kumaran, C. -

Castes and Subcastes List in Kerala

Castes and Subcastes List in Kerala: State Id State Name Castecode Caste Subcaste 1 KERALA 1001 ACHARI KONGU VELLALA 1 KERALA 1002 ACHARI VISHWAKARMA 1 KERALA 1003 ACHARI 1 KERALA 1004 ADI DRAVIDA PARAYA 1 KERALA 1005 AENTELUR ROMAN CATHOLIC 1 KERALA 1006 AMBATTAN 1 KERALA 1007 ARAYAN DEVARA 1 KERALA 1008 ARAYAN 1 KERALA 1009 BARBAR 1 KERALA 1010 BRAHMAN BHATT 1 KERALA 1011 BRAHMAN IYER 1 KERALA 1012 BRAHMAN 1 KERALA 1013 CATHOLIC LATIN CATHOLIC 1 KERALA 1014 CATHOLIC PULAYA 1 KERALA 1015 CATHOLIC ROMAN CATHOLIC 1 KERALA 1016 CATHOLIC SYRIAN 1 KERALA 1017 CATHOLIC 1 KERALA 1018 CHAKKILIYAN AMMA 1 KERALA 1019 CHAKKILIYAN 1 KERALA 1020 CHERUMAN IRAYA 1 KERALA 1021 CHERUMAN KANAKKAN 1 KERALA 1022 CHERUMAN 1 KERALA 1023 CHETTIAR CHAKKA 1 KERALA 1024 CHETTIAR TELUGU 1 KERALA 1025 CHETTIAR TELUGU CHETTIAR 1 KERALA 1026 CHETTIAR VANIAR 1 KERALA 1027 CHETTIAR 1 KERALA 1028 CHRISTIAN CATHOLIC 1 KERALA 1029 CHRISTIAN CHRISTIAN https://www.matchfinder.in/malayalam-matrimony This list is provided for free by the courtesy of Matchfinder Matrimony 1 KERALA 1030 CHRISTIAN ROMAN CATHOLIC 1 KERALA 1031 CHRISTIAN 1 KERALA 1032 DHOBI 1 KERALA 1033 DWEEPARA 1 KERALA 1034 EZHAVA AMMELU 1 KERALA 1035 EZHAVA CHETTI 1 KERALA 1036 EZHAVA EZHAVA 1 KERALA 1037 EZHAVA GHIYAIU 1 KERALA 1038 EZHAVA HARIJAN 1 KERALA 1039 EZHAVA KONGU VELLALA 1 KERALA 1040 EZHAVA MENON 1 KERALA 1041 EZHAVA PANKAR 1 KERALA 1042 EZHAVA PILLAI 1 KERALA 1043 EZHAVA THEYAHAN 1 KERALA 1044 EZHAVA THIYA 1 KERALA 1045 EZHAVA VANIKA 1 KERALA 1046 EZHAVA VANIYAN 1 KERALA 1047 EZHAVA VARRER 1 KERALA 1048 EZHAVA VATHI 1 KERALA 1049 EZHAVA 1 KERALA 1050 EZHUTHACHAN 1 KERALA 1051 G.S.B. -

PROSPECTUS for ADMISSION to POST GRADUATE DEGREE PROGRAMMES (MGU-CSS), B Lisc & B P Ed in AFFILIATED COLLEGES THROUGH CENTRALISED ALLOTMENT PROCESS (CAP)

PROSPECTUS FOR ADMISSION TO POST GRADUATE DEGREE PROGRAMMES (MGU-CSS), B LiSc & B P Ed IN AFFILIATED COLLEGES THROUGH CENTRALISED ALLOTMENT PROCESS (CAP) 2021 MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY PRIYADARSINI HILLS P.O., KOTTAYAM-686 560 www.cap.mgu.ac.in SCHEDULE - 2021 2 From the Vice Chancellor’s Desk Mahatma Gandhi University, one of the major affiliating universities in Kerala, is the premier educational institution that strives to fulfill the higher educational needs of the people of Central Kerala. Its headquarters is at Priyadarshini Hills, 13 kms off Kottayam and the campus is spread in an area of 110 acres. The University also has satellite campuses in parts of Kottayam and the neighbouring districts. The University was established on 2 October 1983 and has jurisdiction over the revenue districts of Kottayam, Ernakulam, Idukki and parts of Pathanamthitta and Alappuzha. Its academic universe consists of 18 University Schools/Departments, 8 Inter-University Centres, 10 Inter School Centres and 264 Affiliated Colleges. The University has achieved tremendous progress in securing a good number of research and extension projects under the auspices of national agencies and institutions like UGC, FIST, DRS, ISRO, COSIT, CSIR, DAAD, STEC, ICMR, BARC, MoEF, ICCR, ICHR, IED, IIFT, and the Sahitya Academy. There is considerable advance made in the University’s execution of MoUs with research institutions of international reputation. The MoUs entered into with Max Planck Institute of Technology, Germany; Brown University, USA; University of Nantes, France; California Institute of Technology, USA; University of Toronto, Canada; Catholic University, Belgium; Heidelberg University, Germany; and the Institute of Political Studies, Rennes, France, and Jinan University, China are only a few of them. -

Sumi Project

1 CONTENTS Introduction............................................................................................ 3-11 Chapter 1 Melting Jati Frontiers ................................................................ 12-25 Chapter 2 Enlightenment in Travancore ................................................... 26-45 Chapter 3 Emergence of Vernacular Press; A Motive Force to Social Changes .......................................... 46-61 Chapter 4 Role of Missionaries and the Growth of Western Education...................................................................... 62-71 Chapter 5 A Comparative Study of the Social Condions of the Kerala in the 19th Century with the Present Scenerio...................... 72-83 Conclusion ............................................................................................ 84-87 Bibliography .......................................................................................88-104 Glossary ............................................................................................105-106 2 3 THE SOCIAL CONDITIONS OF KERALA IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO TRAVANCORE PRINCELY STATE Introduction In the 19th century Kerala was not always what it is today. Kerala society was not based on the priciples of social freedom and equality. Kerala witnessed a cultural and ideological struggle against the hegemony of Brahmins. This struggle was due to structural changes in the society and the consequent emergence of a new class, the educated middle class .Although the upper caste