Court of Conscience Issue 13, 2019 Boats and Borders: Australia's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Project Safecom News and Updates Thursday, 25 January 2018

Project SafeCom News and Updates Thursday, 25 January 2018 Support us by making periodic donations: https://www.safecom.org.au/donate.htm 1. Parents demand Aung San Suu Kyi is cut from children’s book of role models 2. Sexual harassment and assault rife at United Nations, staff claim 3. Same-sex marriage sparks push for Australian bill of rights 4. Cate Blanchett urges Davos to give refugees more compassion 5. Australia's human rights record attacked in global report for 'serious shortcomings' 6. Declassified government documents: Refugee status reforms 7. Second group of Manus Island refugees depart for US under resettlement deal 8. Second group of refugees leave Manus bound for the United States 9. MEDIA RELEASE: Nauru refugees petition against delays and exclusion from the US 10. MEDIA RELEASE: Hunger strike over detention visit restrictions continues 11. Immigration detainees launch hunger strike 12. Malcolm Turnbull, Jacinda Ardern at odds over claim New Zealand is fuelling people smuggling 13. John Birmingham: There are votes in race-baiting and that's a stain on us all 14. Joumanah El Matrah: The feared other: Peter Dutton's and Australia's pathology around race 15. Labor lambasts Dutton for 'playing to the crowd' over Melbourne crime comments 16. Legal body says rule of law threatened after Dutton's criticism of judiciary 17. Greg Barns: Time to challenge the type of politics that plays the fear card 18. Dutton refuses Senate order to release details of refugee service contracts on Manus 19. Dutton's attacks on the judiciary are anything but conservative 20. -

Refugee Writing and the Australian Border As Literary Interface

‘Where We Are Is Too Hard’: Refugee Writing and the Australian Border as Literary Interface BRIGITTA OLUBAS University of New South Wales On the occasion of his arrival in New Zealand in November 2019, after six years spent in the Australian Government-controlled detention centre on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea, Kurdish–Iranian journalist Behrouz Boochani announced: ‘I am Australian. ... I, as a stateless person, will never go to Australia, but I spoke to Australians, I participated in events at universities, I wrote to the Australian people, to share the story of their Manus. I tried to make Australia a better place’ (Doherty). Even before this assertion, his book No Friend but the Mountains had been embraced into the canon of Australian Literature by virtue of its passionate embrace by Australian readers, receiving a succession of major literary awards, and entering the best-seller lists. In the year after its publication, Boochani had become a regular guest at literary festivals, appearing via video- or audio-link, participating in the deep literary life of the nation even as he was being held in dire conditions with hundreds of other men, in Manus Prison.1 Boochani’s status as an Australian writer, then, is fraught and complex, and necessary. It demands of his readers that they engage not simply with his work but with the idea of him as an Australian writer, and with the cognate locution of Australian Literature. This essay aims to take some first steps toward that engagement, to set out some of its imperatives, and to propose some larger aesthetic contexts within which it might be staged. -

Interview: André Dao and Behrouz Boochani*

Law Text Culture Volume 24 Article 2 2020 Interview: Andre ́ Dao and Behrouz Boochani André Dao [email protected] Behrouz Boochani [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Dao, André and Boochani, Behrouz, Interview: Andre ́ Dao and Behrouz Boochani, Law Text Culture, 24, 2020, 50-59. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol24/iss1/2 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Interview: Andre ́ Dao and Behrouz Boochani Abstract The following text is an edited transcript of a conversation, conducted in English, between Andre ́ Dao and Behrouz Boochani, two of the artists who made how are you today: Andre ́ from Melbourne, Australia, Behrouz during his incarceration on Manus island, Papua New Guinea. The conversation took place on 3 December in plenary at the 2019 meeting of the Law, Literature and Humanities Association of Australasia, on Yugambeh land in the Gold Coast. Boochani had arrived in Aotearoa, New Zealand barely two weeks before, following more than six years of detention on Manus Island, having originally sought asylum in Australia. This journal article is available in Law Text Culture: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol24/iss1/2 Interview: André Dao and Behrouz Boochani* André Dao and Behrouz Boochani The following text is an edited transcript of a conversation, conducted in English, between André Dao and Behrouz Boochani, two of the artists who made how are you today: André from Melbourne, Australia, Behrouz during his incarceration on Manus island, Papua New Guinea. -

Watching Refugees: a Pacific Theatre of Documentary

Watching Refugees: A Pacific Theatre of Documentary GILLIAN WHITLOCK UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND Robert Dixon’s studies of international media and ‘cultures of the periphery’ (Esau cited in Dixon, Photography xxiv), Prosthetic Gods (2001) and Photography, Early Cinema and Colonial Modernity (2012), map Southern imaginaries in the visual cultures of colonial modernity, introducing a conceptual geography of photography and early cinema that moves beyond the nation to the Pacific, and to stage and screen in the Anglosphere of the Global North. Dixon observes in his case study of Hurley’s pseudo-ethnographic travelogues filmed in Papua, Pearls and Savages (1921) and With the Headhunters of Unknown Papua (1923), that Frank Hurley was a ‘master of the new media’ and ‘modern visuality’ (Early Cinema 217).1 Here, as he does so often in his writing on literary and visual cultures, Dixon challenges scales of interpretation calibrated in terms of the nation, mapping distinctive Southern cultural formations in the Pacific that coincided with a period of active promotion by the Australian Territorial administration of a white settler society based on a plantation economy in the colony. These studies of visual culture in colonial modernity transform approaches to cultures of the periphery and turn to alternative conceptual geographies, organised in terms of the network or web, and multi-centred innovations and exchanges (210). They inspire thinking about a Pacific ‘theatre’ of documentary here in this essay. The concept of multiple and conflicting refugee imaginaries—‘complex sets of historical, political, legal and ethical relations that tie all of us— citizens of nation states and citizens of humanity only—together’ (Woolley et al. -

The Politicisation of Seeking Asylum Manus Prison Theory and Australia’S Response to Asylum Seekers

Webinar The politicisation of seeking asylum Manus Prison theory and Australia’s response to asylum seekers Asylum seekers have occupied a particular place in the Australian national imaginary, particularly in the post-Tampa era after 2001. Over that time, successive ALL WELCOME Australian governments have pursued a militarised enforcement approach to national borders when it comes to people seeking asylum. This includes the FREE EVENT implementation of ‘Operation Sovereign Borders’ – the consolidation of a Online seminar mandatory offshore detention and processing policy for anyone seeking asylum who arrives by boat and the controversial and dangerous ‘tow-back policy’. There Wednesday October 28, 2020 has been a range of policy and legislative changes that have made seeking asylum 10am-1pm (AEST, Sydney) in Australian more difficult, such as indefinite processing times, denying access to Register at Eventbrite: family reunion and government-funded legal assistance, and removing the right to https://politicsseekasylum.eve independent reviews of refugee claims, among others. There are also operations that systematically censor information regarding asylum seekers - restricting media ntbrite.com.au access to detention facilities, controlling information flows, and leveraging positions of power to manage the narrative. The most controversial and intractable has been the offshoring of immigration of detention to the countries of Nauru and Papua New Guinea (Manus Island). The symposium will be informed by the Manus CONVENORS Prison theory that has been further developed by the analysis of former Manus Rachel Sharples detainee Behrouz Boochani and his translator and collaborator, Omid Tofighian. Western Sydney University [email protected] This interdisciplinary symposium will therefore take an overtly political and innovative conceptual approach to this problem. -

Court of Conscience Issue 13, 2019 Boats and Borders: Australia’S Response to Refugees and Asylum Seekers Court of Conscience Issue 13, 2019

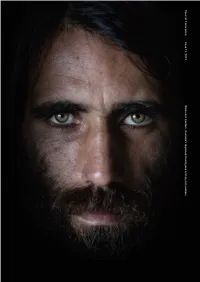

Court of Conscience Issue 13, 2019 Boats and borders: Australia’s response to refugees and asylum seekers Court of Conscience Issue 13, 2019 Boats and borders: Australia’s response to refugees and asylum seekers Court of Conscience respectfully acknowledges the Bedegal, Gadigal and the Ngunnawal Peoples as the custodians and protectors of the lands where each campus of UNSW is located. Front cover: Iranian-Kurdish asylum seeker Behrouz Boochani. Boochani is a writer, journalist and Associate Professor at UNSW, and was held on Manus Island from 2013 until its closure in 2017 (Jonas Gratzer) Editorial team Jacob Lancaster Calum Brunton Brian Wu Contents Editor-in-Chief Editor Editor Jacob Lancaster is a fifth year Calum Brunton is a second year Arts/Law Brian is a second year Commerce/ Science/Law student whose caffeine student who enjoys cycling and walking Law student with an interest in addiction is best understood with in the mountains. In his spare time he learning new languages as a means reference to his TSA approved, travel- can be found in the kitchen perfecting his of gaining an insight into different sized espresso machine. homemade chilli oil or locked in a staring cultures. Having retained around half contest with the unread pile of books at of his French vocabulary from high Beatriz Linsao the end of his bed. school and able to name more than Managing Editor ten types of Italian pasta, his next Beatriz Linsao is a fourth year Arts/Law Glenda Foo linguistic challenge is to try to master student and just your average girl. -

Acts of Resistance by Detained People Seeking Asylum, and in the Performance Art of Mike Parr

Wounded bodies as sites of dissensus: Acts of resistance by detained people seeking asylum, and in the performance art of Mike Parr A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Elizabeth Gay BA (Hons) Performance Studies, Victoria University School of Media and Communication College of Design and Social Context RMIT University December 2019 Declaration I certify that except where due acknowledgement has been made, the work is that of the author alone; the work has not been submitted previously, in whole or in part, to qualify for any other academic award; the content of the thesis is the result of work which has been carried out since the official commencement date of the approved research program; any editorial work, paid or unpaid, carried out by a third party is acknowledged; and ethics procedures and guidelines have been followed. I acknowledge the support I have received for my research through the provision of an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Elizabeth Gay 10 December 2019 ii Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which this thesis was written, the sacred and sovereign lands of the people of the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nations. I acknowledge that the sovereignty of these lands has never been ceded and I respectfully acknowledge their Elders past, present and emerging. I acknowledge the disrespect and brutality with which my ancestors illegally occupied these lands and that I benefit from this as an occupier. I acknowledge and apologise for the continuing acts of colonial power, racism and violence which disregard the transgenerational trauma and pain of dispossession for Aboriginal people. -

Social Science Stars Melbourne, September 2018

Audio recording transcript: Social Science Stars Melbourne, September 2018 Thijs van Vlijmen: Hello, my name is Thijs van Vlijmen and I'm Associate Editorial Director for academic journals at Routledge in Australia. Divya Das: Hi, I'm Divya Das and I run CHASS, Council for the Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences. Thijs V.: We are pleased to present a recording of our Social Science Stars event, which was held in September 2018 in Melbourne at RMIT. You're about to listen to Robert Manne and Leanne Weber. We hope you enjoy it. Divya Das: Hi everyone, good afternoon. Welcome to Social Sciences Stars in Melbourne. I'm Divya Das. I run the Council for the Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, CHASS. Before we begin today's proceedings, I would like to acknowledge the people of the Woiwurrung and Boon Wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nations on whose lands we meet. We respectfully acknowledge their ancestors and elders past and present. Divya Das: Social Sciences Stars is a series of public events being organized by CHASS in collaboration with publishers Routledge/Taylor & Francis, and The Conversation. This series is running through Australia's inaugural National Social Sciences Week. We've been in Canberra and Sydney earlier this week and Melbourne is our last stop. The world of HASS, Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, is goin g through some challenging times. As we face new challenges, Social Sciences Stars is our attempt to showcase critical social science research and get you thinking about why the world needs it now more than ever. -

Refugee Journeys Histories of Resettlement, Representation and Resistance

REFUGEE JOURNEYS HISTORIES OF RESETTLEMENT, REPRESENTATION AND RESISTANCE REFUGEE JOURNEYS HISTORIES OF RESETTLEMENT, REPRESENTATION AND RESISTANCE EDITED BY JORDANA SILVERSTEIN AND RACHEL STEVENS Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464189 ISBN (online): 9781760464196 WorldCat (print): 1232438634 WorldCat (online): 1232438632 DOI: 10.22459/RJ.2021 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover artwork: Zohreh Izadikia, Freedom, 2018, Melbourne Artists for Asylum Seekers. This edition © 2021 ANU Press CONTENTS Acknowledgements . vii Contributors . ix Refugee journeys . 1 Jordana Silverstein and Rachel Stevens Part I: Labelling refugees 1 . Australian responses to refugee journeys: Matters of perspective and context . 23 Eve Lester 2 . Once a refugee, always a refugee? The haunting of the refugee label in resettlement . 51 Melanie Baak 3 . ‘His happy go lucky attitude is infectious’: Australian imaginings of unaccompanied child refugees, 1970s–1980s . .. 71 Jordana Silverstein 4 . ‘Foreign infiltration’ vs ‘immigration country’: The asylum debate in Germany . 89 Ann-Kathrin Bartels Part II: Flashpoints in Australian refugee history 5 . The other Asian refugees in the 1970s: Australian responses to the Bangladeshi refugee crisis in 1971 . 111 Rachel Stevens 6 . Race to the bottom: Constructions of asylum seekers in Australian federal election campaigns, 1977–2013 . 135 Kathleen Blair 7 . Behind the wire: An oral history project about immigration detention . -

International Criminal Law and the Violence Against Migrants

German Law Journal (2020), 21, pp. 571–597 doi:10.1017/glj.2020.24 ARTICLE International Criminal Law and the Violence against Migrants Ioannis Kalpouzos* (Received 24 February 2020; accepted 03 March 2020) Abstract Should we use the language of international criminal law (ICL) to discuss, analyze, and address Western policies of migration control? Such policies have included or resulted in indefinite and inhumane deten- tion, deportations, including through practices of push- and pull-backs and numerous deaths of migrants attempting to cross land or sea borders. And yet, recourse to ICL’s conceptual and rhetorical apparatus, often reserved for “unimaginable atrocities,” may seem ill-fitting and an emotive stretch of doctrine. Drawing from international strategic litigation practice on Australian and European policies, this article examines whether the legal concept of crimes against humanity can apply to the deaths, detention, and deportation of migrants, as part and consequence of Western policies of migration control. As migration control policies involve increasingly sophisticated practices of outsourcing and responsibility avoidance, I further ask whether the tools ICL has developed to describe system criminality can trace individual liability against the distance created by such policies. I also inquire into the potential that the transnational nature of migration and the spreading of anti-migration policies have in activating the jurisdiction of courts and the prioritization of the role of the International Criminal Court. Finally, I consider the danger of fetish- izing an international punitive approach, before offering some thoughts that aim to bridge a critical approach to international criminal law with its use in meaningful strategic litigation. -

Behrouz Boochani's

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF LIFE WRITING VOLUME VII(2018)CP176–CP182 The Diary of a Disaster: Behrouz Boochani’s ‘asylum in space’ Gillian Whitlock A diary is not only a place of asylum in space; it is also an archive in time…. Phillipe Lejeune (On Diary 324) On Autobiography is a selection of eleven essays translated into English from Philippe Lejeune’s major studies, Le Pacte autobiographique, Lire Leiris, autobiographie et langage, Je est un autre and Moi aussi. In his editorial Foreword Paul John Eakin remarks that some of the range and authority of Lejeune’s studies of autobiography have been lost in translation. As a result, recognition of his contribution to autobiography studies as an his- torian, critic and theorist remains limited, and criticism in English tends to focus on the formalist and generic orientation of his early work on the autobiographical pact. What goes missing are the social and historical dimensions of his work on autobiography, and his enduring interest in ‘micro-forms’ of autobiographical discourse and the work that they do: how does autobiographical discourse circulate today? who engages in it? who reads it? where does it come from? (xxii). For post colonial scholarship in particular, Lejeune’s questions about how ‘those who are controlled’ become agents in the creation of life narratives endure. Philippe Lejeune is himself always meticulous about the social, historical and cultural focus of his research in Western modernity, and specifically in France—he is tentative, for example, when asked to address a conference on auto- biography and life writing in Algeria, but he welcomes the opportunity to think about how his study of the diary in France might be applied to other countries with very different cultures (On Diary 267). -

Bordering Creating, Contesting and Resisting Practice

borderlands DOI | 10.21307/borderlands-2020-001 Vol 19 | No 1 2020 Bordering Creating, contesting and resisting practice SPECIAL ISSUE, VOL. 2 ELISE KLEIN Australian National University Abstract UMA KOTHARI Materially and symbolically manifest, borders are shaped by University of Manchester, UK history, politics and power. This second special issue of a two- part series brings together an international collective of authors Editors who presented their papers at a conference on Technologies of Bordering convened by the editors at the University of Melbourne, Australia in July 2019. We invited presentations that critically engage with multiple and varied forms of bordering as expressions of power and oppression, as well as those that considered the possibilities and aspirations for more hopeful and progressive futures. Articles explored a range of issues from borders within and beyond detention centres and carceral systems to colonial and postcolonial forms of bordering. Drawing on a variety of empirical research across different spaces and scales, a range of theoretical perspectives and a diversity of methodological approaches, the articles collectively address the material, digital, virtual and human technologies that divide, exclude, contain, control and govern humans and non-humans. Keywords: asylum, nonhumans, materiality, borders, refugees © 2020 Elise Klein and Uma Kothari and borderlands journal. This is an Open Access article licensed under the Creative 1 Commons License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ bordering Introduction Materially and symbolically manifest, borders are shaped by history, politics and power. They take various forms, have multiple functions and are ceaselessly changing, from the building of a new Mexico-US wall, the collection of bio-metric data in India to the creation of national parks that delimit human and non-human mobility.