T12.1 Colonization by People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking Responses to Coastal Problems: an Analysis of the Opportunities and Constraints for Canada

RETHINKING RESPONSES TO COASTAL PROBLEMS: AN ANALYSIS OF THE OPPORTUNITIES AND CONSTRAINTS FOR CANADA by Colleen S. L. Mercer Clarke Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia June 2010 © Copyright by Colleen S. L. Mercer Clarke, 2010 DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY INTERDISCIPLINARY PHD PROGRAM The undersigned hereby certify that they have read and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate Studies for acceptance a thesis entitled “RETHINKING RESPONSES TO COASTAL PROBLEMS: AN ANALYSIS OF THE OPPORTUNITIES AND CONSTRAINTS FOR CANADA” by Colleen S. L. Mercer Clarke in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Dated: June 4, 2010 Supervisor: _________________________________ Supervisor: _________________________________ Readers: _________________________________ _________________________________ _________________________________ ii DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY DATE: 4 June 2010 AUTHOR: Colleen S. L. Mercer Clarke TITLE: RETHINKING RESPONSES TO COASTAL PROBLEMS: AN ANALYSIS OF THE OPPORTUNITIES AND CONSTRAINTS FOR CANADA DEPARTMENT OR SCHOOL: Interdisciplinary PhD Program DEGREE: PhD. CONVOCATION: October YEAR: 2010 Permission is herewith granted to Dalhousie University to circulate and to have copied for non-commercial purposes, at its discretion, the above title upon the request of individuals or institutions. _______________________________ Signature of Author The author reserves other publication rights, and neither the thesis nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author‟s written permission. The author attests that permission has been obtained for the use of any copyrighted material appearing in the thesis (other than the brief excerpts requiring only proper acknowledgement in scholarly writing), and that all such use is clearly acknowledged. -

History of Methodism in This Territory Should Be Prepared Especially Dealing with the Past fifty Years Extending from the ’ Date at Which the Late Dr

H I S T O R Y O F ME T HODI SM E ASTE RN BRI TI SH AME RI CA I NCLUDING NOVA SCO TI A, NE W BRUNSWICK PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND NEWFOUNDLAND AND BERMUDA FROM THE BE GI NNI NG TI LL THE CONSUMMATI ON OF U NI ON WI TH THE PRE SBYT E RI AN AND CONGRE GATI ONAL CHURCHE S I N 1925 BY D . W. JOHNS ON ' ‘ OF THE - NOVA SC OTI A CONFERENCE, E X E DI I OB OF THE WESLEYAN C O N T E N T S C h a pte r 1 Th e G e n e si s of Me h o m . t d i s 2 No a Sco on f e r . v tia C e n c e f ol l owin g c ircu it o rd e r a s in Ye a r Book o f 1924 Ne w B un s wi ck a n d Prin ce E dwa s l an d n cl ud n Bib l e r rd I , i i g h s ia n s C in P E . ri t . I N e wfoun d an d Co n fe r e n ce in lu d n L ab ad an E d uc a on l , c i g r or d ti in N e wfoun dl a n d Me th od i s m in Be rmud a Moun t Al llis on In s titution s We s l e ya n a n d Boo k Room C hu rch U n io n ’ Wo man s Mi s s i on a ry So c ie ty Ho m e a n d Fore i g n Mis sion s Ap p e n d ice s T h e C o n s tituti on an d P e r son n e l o f th e E a s te rn British Ame r ica Co n fe re n c e —18 55 to 18 74“ N ova fSco tia C on fe re n c e n am e s an d fig ur e s N B a n d .P E I Con f e e n c me s a n d ur e s . -

C S a S S C É S Canadian Stock Assessment Secretariat Secrétariat Canadien Pour L’Évaluation Des Stocks

Fisheries and Oceans Pêches et Océans Science Sciences C S A S S C É S Canadian Stock Assessment Secretariat Secrétariat canadien pour l’évaluation des stocks Document de recherche 2000/007 Research Document 2000/007 Not to be cited without Ne pas citer sans permission of the authors 1 autorisation des auteurs 1 Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) stock status on rivers in the Northumberland Strait, Nova Scotia area, in 1999 S. F. O’Neil, K.A. Rutherford, and D. Aitken Diadromous Fish Division Science Branch, Maritimes Region Bedford Institute of Oceanography P.O.Box 1006 Dartmouth, N.S. B2Y 4A2 1 This series documents the scientific basis for 1 La présente série documente les bases the evaluation of fisheries resources in scientifiques des évaluations des ressources Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of halieutiques du Canada. Elle traite des the day in the time frames required and the problèmes courants selon les échéanciers documents it contains are not intended as dictés. Les documents qu’elle contient ne definitive statements on the subjects doivent pas être considérés comme des addressed but rather as progress reports on énoncés définitifs sur les sujets traités, mais ongoing investigations. plutôt comme des rapports d’étape sur les études en cours. Research documents are produced in the Les documents de recherche sont publiés dans official language in which they are provided to la langue officielle utilisée dans le manuscrit the Secretariat. envoyé au Secrétariat. This document is available on the Internet at: Ce document est disponible sur l’Internet à: http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas/ ISSN 1480-4883 Ottawa, 2000 i Abstract Fifteen separate rivers on the Northumberland Strait shore of Nova Scotia support Atlantic salmon stocks. -

Atlantic Salmon Stock Status on Rivers in the Northumberland Strait, Nova

Department of Fisheries and Oceans Ministère des pêches et océan s Canadian Stock Assessment Secretariat Secrétariat canadien pour l'évaluation des -stocks Research Document 97/22 Document de recherche 97/22 Not to be cited without Ne pas citer sans permission of the authors ' autorisation des auteurs ' Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L .) stock status on rivers in the Northumberland Strait, Nova Scotia area, in 1996 S. F. O'Neil, D. A. Longard, and C . J. Harvie Diadromous Fish Division Science Branch Maritimes Region P.O.Box 550 Halifax, N .S. B3J 2S7 ' This series documents the scientific basis for ' La présente série documente les bases the evaluation of fisheries resources in Canada . scientifiques des évaluations des ressources As such, it addresses the issues of the day in halieutiques du Canada. Elle traite des the time frames required and the documents it problèmes courants selon les échéanciers contains are not intended as definitive dictés. Les documents qu'elle contient ne statements on the subjects addressed but doivent pas être considérés comme des rather as progress reports on ongoing énoncés définitifs sur les sujets traités, mais investigations . plutôt comme des rapports d'étape sur les études en cours. Research documents are produced in the Les documents de recherche sont publiés dans official language in which they are provided to la langue officielle utilisée dans le manuscrit the Secretariat . envoyé au secrétariat . ii Abstrac t Fifteen separate rivers on the Northumberland Strait shore of Nova Scotia support Atlantic salmon stocks. Stock status information for 1996 is provided for nine of those stocks based on the conservation requirements and escapements calculated either from mark-and-recapture experiments (East River, Pictou and River Philip) or capture (exploitation) rates in the angling fishery. -

Nova Scotia Inland Water Boundaries Item River, Stream Or Brook

SCHEDULE II 1. (Subsection 2(1)) Nova Scotia inland water boundaries Item River, Stream or Brook Boundary or Reference Point Annapolis County 1. Annapolis River The highway bridge on Queen Street in Bridgetown. 2. Moose River The Highway 1 bridge. Antigonish County 3. Monastery Brook The Highway 104 bridge. 4. Pomquet River The CN Railway bridge. 5. Rights River The CN Railway bridge east of Antigonish. 6. South River The Highway 104 bridge. 7. Tracadie River The Highway 104 bridge. 8. West River The CN Railway bridge east of Antigonish. Cape Breton County 9. Catalone River The highway bridge at Catalone. 10. Fifes Brook (Aconi Brook) The highway bridge at Mill Pond. 11. Gerratt Brook (Gerards Brook) The highway bridge at Victoria Bridge. 12. Mira River The Highway 1 bridge. 13. Six Mile Brook (Lorraine The first bridge upstream from Big Lorraine Harbour. Brook) 14. Sydney River The Sysco Dam at Sydney River. Colchester County 15. Bass River The highway bridge at Bass River. 16. Chiganois River The Highway 2 bridge. 17. Debert River The confluence of the Folly and Debert Rivers. 18. Economy River The highway bridge at Economy. 19. Folly River The confluence of the Debert and Folly Rivers. 20. French River The Highway 6 bridge. 21. Great Village River The aboiteau at the dyke. 22. North River The confluence of the Salmon and North Rivers. 23. Portapique River The highway bridge at Portapique. 24. Salmon River The confluence of the North and Salmon Rivers. 25. Stewiacke River The highway bridge at Stewiacke. 26. Waughs River The Highway 6 bridge. -

Riparian Buffer Removal and Associated Land Use in the Sackville River Watershed, Nova Scotia, Canada

Riparian Buffer Removal and Associated Land Use in the Sackville River Watershed, Nova Scotia, Canada Submitted for ENVS 4901/4902 - Honours April 5, 2010 Supervisor: Shannon Sterling By Emily Rideout 0 Abstract “To what extent has riparian area been removed in the Sackville River watershed and what land uses are associated with this riparian area removal?” I investigate this question by assessing the extent of riparian area removal in the Sackville River watershed north of Halifax and characterizing each riparian impact zone with the neighbouring land use. Stream, lake and road data and air photographs are used in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to document the degree of riparian area removal and the land uses associated with the riparian area (agriculture, industry, forestry, residential etc). I consider the riparian area to be a 20m zone extending from the water body’s edge. Over 143km of streams are assessed and all streams are broken down into reaches of discrete lengths based on riparian impact and land use category. Four qualitative indicators of riparian removal are used: Severe, Moderate, Low and Intact. The length of every reach as well as the degree of impact and associated land use are calculated using the summary statistics function in GIS. I found that one third of the total riparian area length is missing up to 50% of its vegetation and that residential, transportation and energy infrastructure were the leading drivers of this riparian buffer removal. I present a map of impacted riparian “hot spots” that will highlight the areas in which riparian area removal is the most severe as well as summaries of the land uses most associated with the greatest degree of riparian vegetation removal. -

South Western Nova Scotia

Netukulimk of Aquatic Natural Life “The N.C.N.S. Netukulimkewe’l Commission is the Natural Life Management Authority for the Large Community of Mi’kmaq /Aboriginal Peoples who continue to reside on Traditional Mi’Kmaq Territory in Nova Scotia undisplaced to Indian Act Reserves” P.O. Box 1320, Truro, N.S., B2N 5N2 Tel: 902-895-7050 Toll Free: 1-877-565-1752 2 Netukulimk of Aquatic Natural Life N.C.N.S. Netukulimkewe’l Commission Table of Contents: Page(s) The 1986 Proclamation by our late Mi’kmaq Grand Chief 4 The 1994 Commendation to all A.T.R.A. Netukli’tite’wk (Harvesters) 5 A Message From the N.C.N.S. Netukulimkewe’l Commission 6 Our Collective Rights Proclamation 7 A.T.R.A. Netukli’tite’wk (Harvester) Duties and Responsibilities 8-12 SCHEDULE I Responsible Netukulimkewe’l (Harvesting) Methods and Equipment 16 Dangers of Illegal Harvesting- Enjoy Safe Shellfish 17-19 Anglers Guide to Fishes Of Nova Scotia 20-21 SCHEDULE II Specific Species Exceptions 22 Mntmu’k, Saqskale’s, E’s and Nkata’laq (Oysters, Scallops, Clams and Mussels) 22 Maqtewe’kji’ka’w (Small Mouth Black Bass) 23 Elapaqnte’mat Ji’ka’w (Striped Bass) 24 Atoqwa’su (Trout), all types 25 Landlocked Plamu (Landlocked Salmon) 26 WenjiWape’k Mime’j (Atlantic Whitefish) 26 Lake Whitefish 26 Jakej (Lobster) 27 Other Species 33 Atlantic Plamu (Salmon) 34 Atlantic Plamu (Salmon) Netukulimk (Harvest) Zones, Seasons and Recommended Netukulimk (Harvest) Amounts: 55 SCHEDULE III Winter Lake Netukulimkewe’l (Harvesting) 56-62 Fishing and Water Safety 63 Protecting Our Community’s Aboriginal and Treaty Rights-Community 66-70 Dispositions and Appeals Regional Netukulimkewe’l Advisory Councils (R.N.A.C.’s) 74-75 Description of the 2018 N.C.N.S. -

The Evaluation of Wetland Restoration Potential Within the Sackville River Secondary Watershed

The Evaluation of Wetland Restoration Potential within the Sackville River Secondary Watershed Report Prepared by: McCallum Environmental Ltd. EVALUATION OF WETLAND RESTORATION POTENTIAL WITHIN THE SACKVILLE RIVER SECONDARY WATERSHED Proponents: Twin Brooks Development Ltd. Armco Capital Inc. Ramar Developments Ltd. Report Prepared by: McCallum Environmental Ltd. May 13, 2013 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this Evaluation of Wetland Restoration Potential (EWRP) study was to identify cost effective, practical and ecologically significant wetland restoration opportunities within the Sackville River Secondary Watershed, Nova Scotia. The EWRP is not a new study methodology in the North American context, but it is a relatively new methodology and study for Atlantic Canada. In Nova Scotia, the Department of Natural Resources owns and operates the Wetlands Inventory Database. This database is currently used to identify wetland habitat in Nova Scotia. However, it is commonly understood within industry and government that this database significantly underrepresents the quality and quantity of wetlands throughout the province of Nova Scotia. Therefore, EWRP first identified and evaluated a GIS tool, the potential wetland layer (PWL), to aid in the identification of potential wetland habitat. This PWL was created for the entire Sackville River Secondary Watershed. In addition to the PWL, a modeled stream layer that was developed by Mr. Raymond Jahncke of Dalhousie University, was also relied upon. It is crucial to note that the PWL is a desktop planning tool only and cannot replace field assessment and appropriate wetland delineation efforts. The PWL can be used to focus field efforts and begin to understand surface water systems across a property. -

Pugwash and Area Community Master Plan

RURAL AND SMALL TOWN PROGRAMME Pugwash and Area Community Master Plan Gwen Zwicker, Cheryl Veinotte and Amanda Marlin September 2010 Rural and Small Town Programme Mount Allison University 144 Main Street Sackville NB E4l 1A7 (Tel) 506-364-2391 (Fax) 506-364-2601 [email protected] www.mta.ca/rstp EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report provides the Village of Pugwash and its community and regional partners with a comprehensive development plan for Pugwash and area. Over the years, a variety of official and unofficial plans have been developed by and for the Village and surrounding area by a number of local authorities including: the Municipality of the County of Cumberland (the Municipality), the Cumberland Regional Economic Association (CREDA), the Village of Pugwash (the Village), and various community- based organizations. In some cases, these plans reflect conflicting needs and priorities. However, taken together, they also represent potential directions in which the area could be headed or developed. What is needed is a clear consensus on the path to take and the priorities which should be addressed. This consensus will need to be developed within regional considerations. A number of new and emerging initiatives concerning tourism, economic development, sustainable development, and infrastructure planning and implementation within Cumberland County need to be considered as part of the process for establishing priorities for action. The scope of this project has been to synthesize the various existing plans and proposed projects, seek community input on priorities, provide a detached third party assessment of needs and priorities, and provide a workable comprehensive master plan for moving this important part of Cumberland County forward. -

Cumberland County Births

RegisterNumber Type County AE Birthday Birthmonth Birthyear PAGE NUMBER Birthplace WHEREM LastName FirstName MiddleName ThirdName FatherFirstName MotherFirstName MotherLastName MarriedDay MarriedMonth MarriedYear TREE ID CODE 325 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 19 1 1866 16 229 TIDNISH NB ? JANE ROBERT JANE SPENCE 7 6 1851 605 2892 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 26 3 1872 170 212 WALLACE WALLACE ABBOT ANNIE LOUISA JOHN MARGT ELLEN CARTER 1870 605 3415 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 25 9 1873 201 331 WALLACE HALIFAX ABBOTT MAGGIE JOHN MAGGIE E CARTER 19 11 1871 605 4048 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 17 4 1875 238 148 SIX MILE ROAD HALIFAX ABBOTT JOHN GORDON JOHN MAGGIE E CARTER 18 11 1871 605 4050 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 17 4 1875 238 151 SIX MILE ROAD HALIFAX ABBOTT WILLIAM JOHN JOHN MAGGIE E CARTER 18 11 1871 605 2962 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 12 9 1872 173 291 SHINNIMICAS SHINNIMICAS ACKIN MARY L ROBERT SARAH ANGUS 13 9 1865 605 4022 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 9 6 1875 236 121 SHINNIMICAS SHINNIMICAS ACKIN SARAH A S ROBERT SARAH ANGUS 13 9 1865 605 110 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 11 6 1865 4 123 TIDNISH TIDNISH ACKLES GEORGE O H.J. ELIZA OXLEY 4 11 605 384 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 5 4 1865 19 293 CROSS ROADS NB ACKLES AVICE CHARLES RUTH ANDERSON 3 11 1844 605 541 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 7 7 1866 29 483 TIDNISH GREAT VILLAGE ACKLES JOHN M JOHN JANE ACKERSON 28 3 1865 605 1117 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 7 12 1867 62 110 NB ACKLES EMILY R JOHN H H.J. -

Topo-Bathymetric Lidar Research for Aquaculture and Coastal Development in Nova Scotia: Final Report

Topo-bathymetric Lidar Research for Aquaculture and Coastal Development in Nova Scotia: Final Report Submitted to Prepared by Applied Geomatics Research Group Bill Whitman NSCC, Middleton Nova Scotia Department of Fisheries and Tel. 902 825 5475 Aquaculture email: [email protected] March 31, 2017 Topo-bathymetric Lidar Research for Aquaculture and Coastal Development in Nova Scotia: Final Report How to cite this work and report: AGRG. 2017. Topo-bathymetric Lidar Research for Aquaculture and Coastal Development in Nova Scotia: Final Report. Technical report, Applied Geomatics Research Group, NSCC Middleton, NS. Copyright and Acknowledgement The Applied Geomatics Research Group of the Nova Scotia Community College maintains full ownership of all data collected by equipment owned by NSCC and agrees to provide the end user who commissions the data collection a license to use the data for the purpose they were collected for upon written consent by AGRG-NSCC. The end user may make unlimited copies of the data for internal use; derive products from the data, release graphics and hardcopy with the copyright acknowledgement of “Data acquired and processed by the Applied Geomatics Research Group, NSCC”. Data acquired using this technology and the intellectual property (IP) associated with processing these data are owned by AGRG/NSCC and data will not be shared without permission of AGRG/NSCC. Applied Geomatics Research Group Page i Topo-bathymetric Lidar Research for Aquaculture and Coastal Development in Nova Scotia: Final Report Executive Summary Three shallow, highly productive, eelgrass-rich estuaries on Nova Scotia’s Northumberland Strait were surveyed in July 2016 using aerial topo-bathymetric lidar to collect seamless land-sea elevation and imagery data. -

Nova Scotia Routes

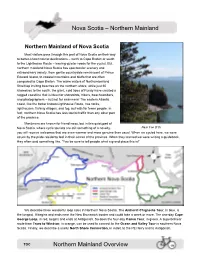

Nova Scotia – Northern Mainland Northern Mainland of Nova Scotia Most visitors pass through this part of Nova Scotia on their way to better-known tourist destinations – north to Cape Breton or south to the Lighthouse Route – leaving quieter roads for the cyclist. But northern mainland Nova Scotia has spectacular scenery and extraordinary variety, from gentle countryside reminiscent of Prince Edward Island, to coastal mountains and bluffs that are often compared to Cape Breton. The warm waters of Northumberland Strait lap inviting beaches on the northern shore, while just 60 kilometres to the south, the giant, cold tides of Fundy have created a rugged coastline that is ideal for shorebirds, hikers, beachcombers, and photographers – but not for swimmers! The eastern Atlantic coast, like the better known Lighthouse Route, has rocks, lighthouses, fishing villages, and fog, but with far fewer people. In fact, northern Nova Scotia has less tourist traffic than any other part of the province. Maritimers are known for friendliness, but in this quiet part of Nova Scotia, where cycle tourists are still something of a novelty, Near Cap D’Or you will receive welcomes that are even warmer and more genuine than usual. When we cycled here, we were struck by the pride residents feel in their corner of the province. When they learned we were writing a guidebook, they often said something like, “You be sure to tell people what a grand place this is!” We describe three wonderful loop rides in Northern Nova Scotia. The Amherst-Chignecto Tour, in blue, is the longest. It begins and ends near the New Brunswick border and could take a week or more.