LEGISLATORS in Support of the Petitioners ______Steven W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Equality South Dakota Political Action Committee

EQUALITY SOUTH DAKOTA POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE 2020 VOTERS GUIDE Race Candidate Party Town District Consists of Candidate endorsed by EqSD PAC based upon survey and past voting record Candidate opposed by EqSD PAC based upon past voting record Candidate having a mixed voting record or mixed survey response New candidate who did not respond to survey Candidate identifies as LGBTQ US Senate Dan Ahlers DEM Dell Rapids US Senate Mike Rounds REP Fort Pierre US House Dusty Johnson REP Mitchell US House Uriah Randy Luallin LIB Hot Springs D01 Senate Michael H Rohl REP Aberdeen Day, Marshall, Roberts D01 Senate Susan Wismer DEM Britton and northern Brown D01 House Jennifer Healy Keintz DEM Eden Counties D01 House Steven D Mccleerey DEM Sisseton Sisseton, Webster, D01 House Tamara St. John REP Sisseton Britton D02 Senate Brock L Greenfield REP Clark Clark, Hamlin, Spink D02 House Kaleb W Weis REP Aberdeen and southern Brown D02 House Lana Greenfield REP Doland Counties D03 Senate Al R Novstrup REP Aberdeen Aberdeen D03 House Carl E Perry REP Aberdeen D03 House Drew Dennert REP Aberdeen D03 House Justin Roemmick DEM Aberdeen D03 House Leslie Mclaughlin DEM Aberdeen D04 Senate John Wiik REP Big Stone City Deuel, Grant and D04 Senate Daryl Root LIB Clear Lake rural Brookings and rural D04 House Becky Holtquist DEM Milbank Codington Counties D04 House Fred Deutsch REP Florence Milbank, Clear Lake D04 House John Mills REP Volga D05 Senate Lee Schoenbeck REP Watertown Watertown D05 Senate Adam Jewell LIB Watertown D05 House Hugh M. Bartels REP Watertown D05 House Nancy York REP Watertown D06 Senate Herman Otten REP Tea Harrisburg, Tea D06 Senate Nancy Kirstein DEM Lennox and Lennox D06 House Cody Ingle DEM Sioux Falls D06 House Aaron Aylward REP Harrisburg D06 House Ernie Otten REP Tea D07 Senate V. -

LEGISLATOR INFORMATION Sen

DISTRICT 7: BROOKINGS DISTRICT 17: VERMILLION LEGISLATOR INFORMATION Sen. V.J. Smith, R-Brookings Sen. Arthur Rusch, R-Vermillion During the legislative session, you may contact your Home/Business Phone: 605/697-5822 Home Phone: 605/624-8723 legislator by writing to: Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] The Honorable (Legislator’s Name) Committees: Education; Military & Veterans Affairs; Committees: Government Operations & Audit; Health Retirement Laws; Taxation, c/o South Dakota (Senate or House) Vice-Chair & Human Services; Judiciary, Vice-Chair Capitol Building Rep. Doug Post, R-Volga Rep. Ray Ring, D-Vermillion 500 E. Capitol Ave. Home Phone: 605/693-6393 Home/Business Phone: 605/675-9379 Pierre, SD 57501-5070 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] You may also contact your legislator(s) during session by Committees: Committee on Appropriations, Joint Committees: Education, Taxation Committee on Appropriations leaving a message with the Senator or House Clerk for a legislator. Rep. Tim Reed, R-Brookings Rep. Nancy Rasmussen, R-Hurley Senate Clerk: 605/773-3821 Home/Business Phone: 605/691-0452 Home Phone: 605/238-5321 House Clerk: 605/773-3851 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] All State Senators and Representatives are elected for Committees: Local Government, Taxation Committees: Education, Judiciary two-year terms. The next general state election will be in 2020. DISTRICT 8: FLANDREAU DISTRICT 21: BURKE, PICKSTOWN, WINNER DISTRICT -

District Legislators Leg. Dist. Aberdeen School District Rep. Steven Mccleerey 1 Rep

District Legislators Leg. Dist. Aberdeen School District Rep. Steven McCleerey 1 Rep. Tamara St. John Sen. Susan Wismer Rep. Lana Greenfield 2 Rep. Kaleb Weis Sen. Brock Greenfield Rep. Drew Dennert 3 Rep. Carl Perry Sen. Al Novstrup Agar-Blunt-Onida School District Rep. Mary Duvall 24 Rep. Tim Rounds Sen. Jeff Monroe Alcester-Hudson School District Rep. David L. Anderson 16 Rep. Kevin Jensen Sen. Jim Bolin Andes Central School District Rep. Kent Peterson 19 Rep. Kyle Schoenfish Sen. Stace Nelson Rep. Caleb Finck 21 Rep. Lee Qualm Sen. Rocky Dale Blare Arlington School District Rep. Fred Deutsch 4 Rep. John Mills Sen. John Wiik Rep. Bob Glanzer 22 Rep. Roger Chase Sen. Jim White Armour School District Rep. Kent Peterson 19 Rep. Kyle Schoenfish Sen. Stace Nelson Rep. Caleb Finck 21 Rep. Lee Qualm Sen. Rocky Dale Blare Avon School District Rep. Kent Peterson 19 Rep. Kyle Schoenfish Sen. Stace Nelson Rep. Caleb Finck 21 Rep. Lee Qualm Sen. Rocky Dale Blare Baltic School District Rep. Jon Hansen 25 Rep. Tom Pischke Sen. Kris Langer Belle Fourche School District Rep. J. Sam Marty 28B Sen. Ryan Maher District Legislators Leg. Dist. Bennett County School District Rep. Steve Livermont 27 Rep. Peri Pourier Sen. Red Dawn Foster Beresford School District Rep. David L. Anderson 16 Rep. Kevin Jensen Sen. Jim Bolin Rep. Nancy Rasmussen 17 Rep. Ray Ring Sen. Arthur Rusch Big Stone City School District Rep. Steven McCleerey 1 Rep. Tamara St. John Sen. Susan Wismer Rep. Fred Deutsch 4 Rep. John Mills Sen. John Wiik Bison School District Rep. -

State Election Results, 2005

Official Publication of the Abstract of Votes Cast for the 2005 Coordinated 2006 Primary 2006 General To the Citizens of Colorado: The information in this abstract is compiled from material filed by each of Colorado’s sixty- four County Clerk and Recorders. This publication is a valuable tool in the study of voting patterns of Colorado voters during the 2005 Coordinated, 2006 Primary, and 2006 General Election. As the State’s chief election officer, I encourage the Citizens of Colorado to take an active role in our democratic process by exercising their right to vote. Mike Coffman Colorado Secretary of State Table of Contents GLOSSARY OF ABSTRACT TERMS .............................................................................................. 4 DISCLAIMER ......................................................................................................................... 6 DIRECTORY .......................................................................................................................... 7 United States Senators .........................................................................................................................7 Congressional Members .......................................................................................................................7 Governor ..........................................................................................................................................7 Lieutenant Governor ...........................................................................................................................7 -

Equality South Dakota Political Action Committee 2018 Voter's Guide

Equality South Dakota Political Action Committee 2018 Voter's Guide EqSD PAC endorses this candidate based upon survey response, voting record or volunteered info EqSD PAC opposes this candidate based upon voting record or other information. This candidate has a mixed voting record or a mixed survey response New candidate on which EqSD PAC does not have any information District Office Party Name City statewide governor Dem Billie Sutton Burke statewide governor Rep Kristi Noem Castlewood statewide governor Liberatian Kurt Evans Wessington Springs statewide US Representative Dem Tim Bjorkman Canistota statewide US Representative Rep Dustin "Dusty" Johnson Mitchell statewide US Representative Liberatian George D. Hendrickson Sioux Falls statewide US Representative Independ Ron Wieczorek Mt. Vernon statewide attorney general Dem Randy Seiler Fort Pierre statewide attorney general Rep Jason Ravnsborg Yankton 1 senate Dem Susan M. Wismer Britton 1 house Dem H. Paul Dennert Columbia 1 house Dem Steven D. McCleerey Sisseton 1 house Rep Tamara St John Sisseton 2 senate Rep Brock L. Greenfield Clark 2 senate Dem Paul Register Redfield 2 house Dem Jenae Hansen Aberdeen 2 house Rep Kaleb W. Weis Aberdeen 2 house Rep Lana J. Greenfield Doland 2 house Dem Mike McHugh Aberdeen 3 senate Rep Al Novstrup Aberdeen 3 senate Dem Cory Allen Heidelberger Aberdeen 3 house Dem Brooks Briscoe Aberdeen 3 house Rep Carl E Perry Aberdeen 3 house Rep Drew Dennert Aberdeen 3 house Dem Justin Roemmick Aberdeen 4 senate Dem Dennis Evenson Clear Lake 4 senate Rep John Wiik Big Stone City 4 house Liberatian Daryl Lamar Root Clear Lake 4 house Rep Fred Deutsch Florence 4 house Dem Jim Chilson Florence 4 house Rep John Mills Volga 4 house Dem Kathy Tyler Big Stone City 5 senate Rep Lee Schoenbeck Watertown 5 house Dem Brett Ries Watertown 5 house Dem Diana Hane Watertown 5 house Rep Hugh M. -

LEGISLATIVE SCORECARD Sdlegislature.Gov

Elevate took a position on nine bills during the 2020 Legislative Session to advocate for the Rapid City business community. This pro- business scorecard reflects the voting record 2020 of local legislators on these key issues. PRO-BUSINESS LEGISLATIVE SCORECARD sdlegislature.gov SB 70 SJR 501 HB 1083 HB 1179 Authorize the use of Spanish in Allows the voters the opportunity Renames postsecondary To allow for series limited obtaining certain driver licenses to approve wagering on sporting technical institutes as technical liability corporations (LLCs) and permits events and revise provisions colleges regarding municipal proceeds of HCR 6017 SB 72 gaming revenues HB 1100 To encourage the creation of To establish the Dakota’s To make an appropriation for a summer study to address Promise scholarship fund HB 1057 (Opposed) a new bioprocessing facility infrastructure and community Transgender surgery and as a joint partnership between needs related to the new B-21 SB 157 hormone blocker prohibition SDSMT and SDSU Mission at EAFB Revise certain provisions regarding the county zoning and appeals process PROPOSED BILLS BUSINESS CHAMPION BUSINESS ADVOCATE Name (District) PERCENT OF 70 72 157 501 1057 1083 1100 1179 6017 PRO-BUSINESS VOTES Sen. Jessica Castleberry (35) Y Y Y Y ◆ Y Y Y Y 100% Rep. Michael Diedrich (34) Y ◆ Y Y Y Y Y Y Y 100% Sen. Helene Duhamel (32) Y Y Y Y Y* Y Y Y Y 100% Rep. Jess Olson (34) Y ◆ Y — Y Y Y Y Y 100% Sen. Jeff Partridge (34) Y Y Y Y ◆ Y Y Y Y 100% Rep. -

Senator Mark Udall (D) – First Term

CBHC Lunchtime Webinar – Preparing for the NCCBH Hill Day in Washington, D.C. June 2010 Working together to develop and deliver health resources to Colorado Communities Colorado Specifics • Colorado has almost 80 people attending this year • CBHC is scheduling meetings with all of the members of Congress on your behalf • CBHC will email virtual Hill Day packets this year to all registered participants – These will include individualized agenda’s for Hill Visits • Please register with the National Council on the website: http://www.thenationalcouncil.org/cs/join_us_in_2010 June 29th, 2010—Hyatt Regency Hotel • Opening Breakfast & Check-in-- 8:00-8:30 a.m. • Policy Committee Meeting Morning Session—8:30-11:45 • "National Council Policy Update" - Linda Rosenberg, President and CEO, National Council • "Implementing Healthcare Reform: New Payment Models" - Dale Jarvis, MCPP Consulting • Participant Briefing Lunch-12:00-1:00 p.m. • "The 2010 Elections Outlook" - Charlie Cook, The Cook Political Report--1:00-2:00 p.m. • "Healthcare Reform and the Medicaid Expansion" - Andy Schneider, House Committee on Energy & Commerce 2:00-3:00 p.m. June 29th Hyatt Regency • Public Policy Committee Meetings 3:15-5:00 p.m. Speakers for the afternoon session include: • "CMS Update" - Barbara Edwards, Director, Disabled and Elderly Health Programs Group, Center for Medicaid, CHIP, and Survey and Certification (CMCS), CMS • "Parity Implementation - What You Should Know and Do" - Carol McDaid, Capitol Decisions, Parity Implementation Coalition June 29—Break Out -

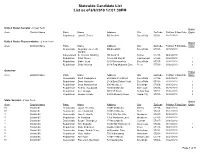

Statewide Candidate List List As of 6/9/2010 12:01:38PM

Statewide Candidate List List as of 6/9/2010 12:01:38PM United States Senator - 6 Year Term Ballot Area District Name Party Name Address City ZipCode Petition Filing Date Order Republican John R. Thune PO Box 841 Sioux Falls 57101- 03/17/2010 United States Representative - 2 Year Term Ballot Area District Name Party Name Address City ZipCode Petition Filing Date Order Democratic Stephanie Herseth PO Box 2009 Sioux Falls 57101- 03/17/2010 Sandlin Independent B. Thomas Marking PO Box 219 Custer 57730- 04/29/2010 Republican Kristi Noem 18575 US Hwy 81 Castlewood 57223- 03/23/2010 1 Republican Blake Curd 38 S Riverview Hts Sioux Falls 57105- 03/27/2010 2 Republican Chris Nelson 2104 Flag Mountain Drive Pierre 57501- 03/02/2010 3 Governor Ballot Area District Name Party Name Address City ZipCode Petition Filing Date Order Democratic Scott Heidepriem 503 East 21st Street Sioux Falls 57105- 03/04/2010 Republican Dave Knudson 2100 East Slaten Court Sioux Falls 57103- 03/31/2010 1 Republican Scott Munsterman 306 4th Street Brookings 57006- 03/30/2010 2 Republican Dennis Daugaard 24930 480th Ave Garretson 57030- 03/15/2010 3 Republican Ken Knuppe HCR 57 Box A Buffalo Gap 57722- 03/26/2010 4 Republican Gordon Howie 23415 Bradsky Road Rapid City 57703- 03/30/2010 5 State Senator - 2 Year Term Ballot Area District Name Party Name Address City ZipCode Petition Filing Date Order 01 District 01 Democratic Jason Frerichs 13497 465th Ave Wilmot 57279- 03/02/2010 02 District 02 Democratic Jim Hundstad 13755 395th Ave Bath 57427- 03/12/2010 3 District 03 Democratic Alan C. -

February 2019 Vol

South Dakota Electric February 2019 Vol. 71 No. 2 Commanding, Controlling Energy Savings Page 8 A Matter of Territorial Integrity Page 12 Tough training. Safe & reliable power. Linemen play a critical role in our mission to provide reliable, affordable electricity. Tough training and a focus on safety is behind everything they do. Simulated field operations and emergency-response training are ways Basin Electric invests in their safety and in providing reliable power to you. Your energy starts here. basinelectric.com BEPC Linemen safety-reliability ad 8-18.indd 1 8/29/2018 3:43:54 PM A LETTER TO SOUTH DAKOTA’S LEGISLATURE South Dakota 2019 Legislative Session: Electric Fairness and ISSN No. 1067-4977 Integrity Produced by the following electric On behalf of South Dakota’s electric cooperatives, I Tough cooperatives in South Dakota and would like to welcome the legislators back to Pierre for western Minnesota: the 2019 legislative session. Your service to your constit- uents and the state is very much appreciated. Black Hills Electric, Custer, S.D. training. Bon Homme Yankton Electric, Tabor, S.D. With at least one of our member systems operating in Butte Electric, Newell, S.D. every county in the state, electric cooperatives represent Cam Wal Electric, Selby, S.D. the strength, independent spirit and diversity that Central Electric, Mitchell, S.D. makes South Dakota such a wonderful place to live. Charles Mix Electric, Lake Andes, S.D. Each of our member cooperatives can trace their roots Safe & Cherry-Todd Electric, Mission, S.D. to humble beginnings, perseverance through chal- Clay-Union Electric, Vermillion, S.D. -

December 31, 2015 the Honorable Kent Lambert Chair, Joint Budget

Physical Address: Mailing Address: 1375 Sherman Street P.O. Box 17087 Denver, CO 80203 Denver, CO 80217-0087 December 31, 2015 The Honorable Kent Lambert Chair, Joint Budget Committee Colorado General Assembly The Honorable Lois Court Chair, House Finance Committee Colorado General Assembly The Honorable Tim Neville Chair, Senate Finance Committee Colorado General Assembly Dear Senators and Representatives: Section 39-22-522.5(12), C.R.S., requires the Department of Revenue (Department) to submit a quarterly report to the Joint Budget Committee and the Finance Committees of the General Assembly which details specific information on the conservation easement (CE) program. The legislation requires information about the number of “tax credits” and “cases” which may be difficult to reconcile with data from the State Court Administrator of the Judicial Department or from the Office of the Attorney General. It is important to note that “tax credits” and “cases” discussed in this report refer to CE donations rather than cases filed in any legal proceeding. Since the inception of the CE program in 2000, there have been 4,295 donations of conservation easements for which tax credits have been claimed. Over 26,000 income tax returns claiming CE tax credits have been filed. The Department has reviewed all of these returns and has disallowed tax credits related to 710 donations. To assist with the understanding of the activity involving these disallowed credits and to comply with statutory reporting requirements, the Department offers the following information: a) For tax years prior to 2014, CE donors are statutorily required to submit an appraisal which provides a value of the CE donated with their tax returns claiming the CE tax credits. -

LEGISLATOR INFORMATION Sen

DISTRICT 7: BROOKINGS DISTRICT 17: VERMILLION LEGISLATOR INFORMATION Sen. V.J. Smith, R-Brookings Sen. Arthur Rusch, R-Vermillion During the legislative session, you may contact your Home/Business Phone: 605/697-5822 Home Phone: 605/624-8723 legislator by writing to: Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] The Honorable (Legislator’s Name) Committees: Education, Military & Veterans Affairs; Committees: Government Operations & Audit; Health Retirement Laws; Taxation, c/o South Dakota (Senate or House) Vice-Chair & Human Services; Judiciary, Vice-Chair Capitol Building Rep. Doug Post, R-Brookings Rep. Ray Ring, D-Vermillion 500 E. Capitol Ave. Home Phone: 605/693-6393 Home/Business Phone: 605/675-9379 Pierre, SD 57501-5070 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] You may also contact your legislator(s) during session by Committees: Committee on Appropriations, Joint Committees: Education, Taxation Committee on Appropriations leaving a message with the Senator or House Clerk for a legislator. Rep. Tim Reed, R-Brookings Rep. Nancy Rasmussen, R-Hurley Senate Clerk: 605/773-3821 Home/Business Phone: 605/691-0452 Home Phone: 605/238-5321 House Clerk: 605/773-3851 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] All State Senators and Representatives are elected for Committees: Local Government, Taxation Committees: Education, Judiciary two-year terms. The next general state election will be in 2020. DISTRICT 8: FLANDREAU DISTRICT 4: BIG STONE CITY Sen. Jordan -

Rapid City, South Dakota July 11–14, 2021 GENERAL INFORMATION

csg midwestern legislative conference Rapid City, South Dakota July 11–14, 2021 GENERAL INFORMATION Unless otherwise indicated in this program, all meeting rooms and events are at The Monument (444 N. Mount Rushmore Road, adjacent to the Holiday Inn Rushmore Plaza). » The CSG Midwest/MLC Office is on the ground level, Room 101. » The Host State Office is on the ground level, Room 102. » The Presenters’ Room is on the upper level, Room 205. » The MLC Registration & Information Desk and CSG-sponsored internet access are on the ground level and available at these times: • Saturday: 12-6 p.m. • Tuesday: 7:30 a.m.-5:30 p.m. • Sunday: 9 a.m.-6 p.m. • Wednesday: 8:30-10 a.m. • Monday: 7:30 a.m.-4 p.m. Attire for the meeting is business casual, unless otherwise indicated (see conference agenda). Attire for the spouse, guest and youth programs is casual, unless otherwise indicated. CSG-sponsored shuttles are available to travel between the Alex Johnson, Rushmore and The Monument/Holiday Inn hotels approximately every 15 minutes (see schedule below). Times could be longer. The pick-up/drop-off location for The Monument/Holiday Inn is on the southwest sidewalk of the Holiday Inn front entrance. The pick-up/drop-off location for the Rushmore Hotel is on the northeast side of the building adjacent to the parking lot; for the Alex Johnson, pick-up/drop-off is outside the front entrance of the hotel. Shuttle schedule:* » Saturday: 11:30 a.m. – 6:30 p.m. » Sunday: 8:30 a.m.