Stagecoach State Trail Master Plan Section 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of Minnesota Department of Natural Resources

STATE OF MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Pursuant to Minnesota Statutes, Section 105.391, Subd. 1, the Commissioner of Natural Resources hereby publishes the final inventory of Protected (i.e. Public) Waters and Wetlands for Nobles County. This list is to be used in conjunction with the Protected Waters and Wetlands Map prepared for Nobles County. Copies of the final map and list are available for inspection at the following state and county offices: DNR Regional Office, New Ulm DNR Area Office, Marshall Nobles SWCD Nobles County Auditor Dated: STATE OF MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES JOSEPH N. ALEXANDER, Commissioner DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF WATERS FINAL DESIGNATION OF PROTECTED WATERS AND WETLANDS WITHIN NOBLES COUNTY, MINNESOTA. A. Listed below are the townships of Nobles County and the township/range numbers in which they occur. Township Name Township # Range # Bigelow 101 40 Bloom 104 41 Dewald 102 41 Elk 103 40 Graham Lakes 104 39 Grand Prairie 101 43 Hersey 103 39 Indian Lake 101 39 Larkin 103 42 Leota 104 43 Lismore 103 43 Little Rock 101 42 Lorain 102 39 Olney 102 42 Ransom 101 41 Seward 104 40 Summit Lake 103 41 Westside 102 43 Wilmont 104 42 Worthington 102 40 B. PROTECTED WATERS 1. The following are protected waters: Number and Name Section Township Range 53-7 : Indian Lake 27,34 101 39 53-9 : Maroney(Woolsten- 32 102 39 croft) Slough 53-16 : Kinbrae Lake (Clear) 11 104 39 Page 1 Number and Name Section Township Range 53-18 : Kinbrae Slough 11,14 104 39 53-19 : Jack Lake 14,15 104 39 53-20 : East Graham Lake 14,22,23,26,27 104 39 53-21 : West Graham Lake 15,16,21,22 104 39 53-22 : Fury Marsh 22 104 39 53-24 : Ocheda Lake various 101;102 39;40 53-26 : Peterson Slough 21,22 101 40 53-27 : Wachter Marsh 23 101 40 53-28 : Okabena Lake 22,23,26,27,28 102 40 53-31 : Sieverding Marsh 2 104 40 53-32 : Bigelow Slough NE 36 101 41 53-33 : Boote-Herlein Marsh 6,7;1,12 102 40;41 53-37 : Groth Marsh NW 2 103 41 53-45 : Bella Lake 26,27,34 101 40 *32-84 : Iowa Lake 31;36 101 38;39 *51-48 : Willow Lake 5;33 104;105 41 2. -

Little Sioux River Watershed Biotic Stressor Identification Report

Little Sioux River Watershed Biotic Stressor Identification Report April 2015 Authors Editing and Graphic Design Paul Marston Sherry Mottonen Jennifer Holstad Contributors/acknowledgements Michael Koschak Kim Laing The MPCA is reducing printing and mailing costs by Chandra Carter using the Internet to distribute reports and Chuck Regan information to wider audience. Visit our website Mark Hanson for more information. Katherine Pekarek-Scott MPCA reports are printed on 100% post-consumer Colton Cummings recycled content paper manufactured without Tim Larson chlorine or chlorine derivatives. Chessa Frahm Brooke Hacker Jon Lore Cover photo: Clockwise from Top Left: Little Sioux River at site 11MS010; County Ditch 11 at site 11MS078; Cattle around Unnamed Creek at site 11MS067 Project dollars provided by the Clean Water Fund (From the Clean Water, Land and Legacy Amendment) Minnesota Pollution Control Agency 520 Lafayette Road North | Saint Paul, MN 55155-4194 | www.pca.state.mn.us | 651-296-6300 Toll free 800-657-3864 | TTY 651-282-5332 This report is available in alternative formats upon request, and online at www.pca.state.mn.us Document number: wq-ws5-10230003a Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 2 Monitoring and assessment ...........................................................................................................2 -

Up the Minnesota Valley to Fort Ridgely in 1853

MINNESOTA AS SEEN BY TRAVELERS UP THE MINNESOTA VALLEY TO FORT RIDGELY IN 1853 The treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota in the summer of 1851 greatly simplified the problem of providing homes for the thousands of immigrants who were flocking to Minnesota Territory. Prior to that date legal settlement had been confined to the region east of the Mississippi below the mouth of the Crow Wing River, but as James M. Goodhue, the editor of the Minnesota Pioneer, wrote in the issue for August 16, 1849, " These Sioux lands [west of the Missis sippi] are the admiration of every body, and the mouth of many a stranger and citizen waters while he looks beyond the Mississippi's flood upon the fair Canaan beyond." Small wonder, then, that Governor Alexander Ramsey worked for a treaty that would open these lands to white settlement. There was much opposition to the treaties in the Senate dur ing the spring of 1852, and they were not ratified until June 23 of that year. Henry H. Sibley, the territorial delegate in Congress, wrote to Ramsey that " never did any measures have a tighter squeeze through."^ Even after they were ratified, the eager settlers legally should have waited until the Indians could be removed and surveys made by the general land office. The land speculator and the settler, however, were not to be balked by such minor details as the presence of Indians and the lack of surveys. They went into the region before it was legally open to settlement and some even planted crops. -

List of Impaired Waters & Tmdls-Regulated Ms4s

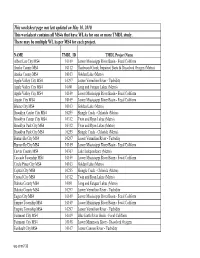

This worksheet page was last updated on May 10, 2010. This worksheet contains all MS4s that have WLAs for one or more TMDL study. There may be multiple WLAs per MS4 for each project. NAME TMDL_ID TMDL Project Name Albert Lea City MS4 10169 Lower Mississippi River Basin - Fecal Coliform Anoka County MS4 10112 Hardwood Creek, Impaired Biota & Dissolved Oxygen (Metro) Anoka County MS4 10103 Golden Lake (Metro) Apple Valley City MS4 10297 Lower Vermilion River - Turbidity Apple Valley City MS4 10091 Long and Farquar Lakes (Metro) Apple Valley City MS4 10169 Lower Mississippi River Basin - Fecal Coliform Austin City MS4 10169 Lower Mississippi River Basin - Fecal Coliform Blaine City MS4 10103 Golden Lake (Metro) Brooklyn Center City MS4 10255 Shingle Creek - Chloride (Metro) Brooklyn Center City MS4 10312 Twin and Ryan Lakes (Metro) Brooklyn Park City MS4 10312 Twin and Ryan Lakes (Metro) Brooklyn Park City MS4 10255 Shingle Creek - Chloride (Metro) Burnsville City MS4 10297 Lower Vermilion River - Turbidity BurnsvilleBurnsville Cit Cityy MS4 10169 LowerLower Mi Mississippississippi RiverRiver BasinBasin - FecalFecal C Coliformoliform Carver County MS4 10367 Lake Independence (Metro) Cascade Township MS4 10169 Lower Mississippi River Basin - Fecal Coliform Circle Pines City MS4 10103 Golden Lake (Metro) Crystal City MS4 10255 Shingle Creek - Chloride (Metro) Crystal City MS4 10312 Twin and Ryan Lakes (Metro) Dakota County MS4 10091 Long and Farquar Lakes (Metro) Dakota County MS4 10297 Lower Vermilion River - Turbidity Eagan City MS4 10169 Lower Mississippi River Basin - Fecal Coliform Empire Township MS4 10169 Lower Mississippi River Basin - Fecal Coliform Empire Township MS4 10297 Lower Vermilion River - Turbidity Fairmont City MS4 10019 Blue Earth River Basin - Fecal Coliform Fairmont City MS4 10168 Lower Minnesota River - Dissolved Oxygen Faribault City MS4 10167 Lower Cannon River - Turbidity wq-strm7-33 This worksheet page was last updated on May 10, 2010. -

External Station ID Schemes May 29, 2008 10:52:57 1117MBR US EPA Region 7 Acronym External Reference Scheme Name Description

External Station ID Schemes May 29, 2008 10:52:57 1117MBR US EPA Region 7 Acronym External Reference Scheme Name Description IDNR Iowa Dept of Natural Resources site ID KDHE Kansas Dept of Health & Environment site ID MDNR Missouri Dept of Natural Resources site ID NDEQ Nebraska Dept of Environmental Quality site ID NPDES National Pollution Discharge Elimination System SECNUMS Legacy Storet Secondary Station IDs Secondary Station Numbers MIGRATED FROM LEGACY STORET ON 13-DEC-99 USGS U S Geologic Survey Station Number Page 1 of 67 External Station ID Schemes May 29, 2008 10:52:57 1119USBR Bureau of Reclamation Acronym External Reference Scheme Name Description SECNUMS Legacy Storet Secondary Station IDs Secondary Station Numbers MIGRATED FROM LEGACY STORET ON 05-FEB-00 Page 2 of 67 External Station ID Schemes May 29, 2008 10:52:57 11DELMOD Delaware River Basin Commission Acronym External Reference Scheme Name Description LOWDEL Lower Delaware Monitoring Program NAWQA USGS National Water Quality Assessment - Delaware River Page 3 of 67 External Station ID Schemes May 29, 2008 10:52:57 11NPSWRD National Park Service Acronym External Reference Scheme Name Description HORIZON Baseline Water Quality Data Inventory and Analysis Baseline Water Quality Data Inventory and Analysis "Horizon" Report assigned Station ID Report sequence value. Note: Some parks (e.g. OZAR) may have continued the ID convention (i.e. OZAR0147) for stations that didn't appear in the Horizon Report. SECSTA1 First Station Alias/Name/ID from Legacy STORET SECSTA2 Second Station Alias/Name/ID from Legacy STORET SECSTA3 Third Station Alias/Name/ID from Legacy STORET Page 4 of 67 External Station ID Schemes May 29, 2008 10:52:57 211WVOWR Division of Water and Waste Management Acronym External Reference Scheme Name Description WAPBASE Watershed Assesment Program Data Base Page 5 of 67 External Station ID Schemes May 29, 2008 10:52:57 21COL001 Colorado Dept. -

USDA-NRCS IOWA STATE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE MEETING Neal Smith Federal Building 210 Walnut Street, Room 693 Virtual Meeting - Teleconference Des Moines, Iowa 50309

USDA-NRCS IOWA STATE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE MEETING Neal Smith Federal Building 210 Walnut Street, Room 693 Virtual Meeting - Teleconference Des Moines, Iowa 50309 September 17, 2020 at 1:00 P.M. DRAFT MINUTES Welcome/Opening Comments – Kristy Oates, Acting State Conservationist Kristy opened the meeting, expressed her appreciation for everyone attending virtually, and roll call was accomplished (Attachment A). Kristy stated that she is on detail from Texas and it was announced today that Jon Hubbert has been selected as the new State Conservationist. Jon will begin his duties in that position on October 11, 2020. Kristy reported that there are several postings currently on the federal register: • USDA is seeking nominations for the Task Force on Agricultural Air Quality Research; • USDA is seeking input for Ready to Go Technologies and Practices for Agriculture Innovation Agenda, and; • The rule was posted for determining whether land is considered highly erodible or a wetland which followed the interim final rule published December 7, 2018. • Of note, additional information on the Air Quality Task Force and Ready to Go Technologies and Practices will be posted on the State Technical Committee page of the Iowa NRCS website. Kristy also reported that in response to the derecho storm event, NRCS developed a special EQIP signup for seeding cover crops on impacted fields, replacing roofs, covers, or roof run off structures previously funded through NRCS and replacing damaged high tunnel systems previously funded through NRCS. Producers may request early start waivers to begin implementing practices immediately. Landowners with windbreak and shelterbelt tree damage may apply for NRCS assistance through general EQIP. -

Geology and Ground-Water Resources of Nobles County and Part of Jackson County Minnesota

Geology and Ground-Water Resources of Nobles County and Part of Jackson County Minnesota 3EOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1749 Prepared in cooperation with the Division of Heaters, Minnesota Department of Conservation, and the city of fForthington Geology and Ground-Water Resources of Nobles County ind Part of Jackson County Minnesota fy RALPH F. NORVITCH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1749 Prepared in cooperation with the Division of Waters, Minnesota Department of Conservation, ind the city of Worthington UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1964 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director The U.S. Geological Survey Library catalog card for this publication appears after index. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.G. 20402 CONTENTS Page Abstract_______________________________________________________ 1 Introduction._____________________________________________________ 2 Location and extent-__-________________________-______________ 2 Purpose and scope.-___________________________________________ 3 History and methods of investigation_________________________-__ 4 Acknowledgments. ____________________________________________ 5 Previous reports_____________________________________________ 5 Well-numbering system________________________________________ 5 Geography_____________________________________________________ 7 Culture-___________________________________________________ 7 Climate. -

![Ch 65, P.47 Environmental Protection[567] IAC 10/9/96, 12/17/97 Black Hawk Beaver Creek Black Hawk Creek Buck Creek Cedar River](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7063/ch-65-p-47-environmental-protection-567-iac-10-9-96-12-17-97-black-hawk-beaver-creek-black-hawk-creek-buck-creek-cedar-river-3957063.webp)

Ch 65, P.47 Environmental Protection[567] IAC 10/9/96, 12/17/97 Black Hawk Beaver Creek Black Hawk Creek Buck Creek Cedar River

IAC 10/9/96, 12/17/97 Environmental Protection[567] Ch 65, p.47 Black Hawk Beaver Creek Mouth, S34, T90N, R14W to West County IAC 10/9/96, 12/17/97 Line, S31, T90N, R14W Black Hawk Creek Mouth, S22, T89N, R13W to West County Line S6, T87N, R14W Buck Creek All Cedar River All Crane Creek Mouth to North County Line Miller’s Creek Mouth to West Line, S5, T87N, R12W Shell Rock River Mouth, S4, T90N, R14W to North County Line, S4, T90N, R14W Spring Creek Mouth to Confluence with Little Spring Creek, S11, T87N, R11W Wapsipinicon River All West Fork Cedar River All Wolf Creek Mouth, S19, T87N, R11W to South County Line Boone Beaver Creek West Line of S10, T82N, R28W to South County Line Des Moines River All Squaw Creek West Line of S8, T85N, R25W to East County Line Bremer Cedar River All Crane Creek South County Line to North Line, S9, T91N, R12W East Fork Wapsipinicon River Mouth to North County Line Little Wapsipinicon River East County Line to North Line, S2, T92N, R11W Quarter Section Run Mouth to West Line, S35, T91N, R13W Shell Rock River All Wapsipinicon River All Buchanan Buck Creek Mouth to West County Line Buffalo Creek Mouth to Confluence of East and West Branches, S35, T90N, R8W Little Wapsipinicon River Mouth to North County Line Otter Creek Mouth to Confluence with Unnamed Creek, S9, T90N, R9W Wapsipinicon River All Buena Vista Little Sioux River All North Raccoon River South County Line to North Line of S15, T91N, R36W Ch 65, p.48 Environmental Protection[567] IAC 7/11/01 Butler Beaver Creek All Boylan Creek Mouth to North Line, -

DATE: December 11, 2018 TO: Board of Water and Soil Resources

DATE: December 11, 2018 TO: Board of Water and Soil Resources’ Members, Advisors, and Staff FROM: John Jaschke, Executive Director SUBJECT: BWSR Board Meeting Notice – December 19, 2018 The Board of Water and Soil Resources (BWSR) will meet on Wednesday, December 19, 2018, beginning at 9:00 a.m. The board meeting will be held at the Eagan Community Center – South Oaks Room, located at 1501 Central Parkway, Eagan, MN 55121. The following information pertains to agenda items: COMMITTEE RECOMMENDATIONS Grants Program and Policy Committee 1. Performance Review and Assistance Program (PRAP) Assistance Grants – The purpose of this agenda item is to revise the authorization of the Performance Review and Assistance Program (PRAP) approved in June 2018 through order #18-41. The previous board order restricted the source of funds that could be used for the grants to returned state cost share funds. This has limited the ability to issue grants because the amount of returned state cost share funds has decreased significantly in the past several years. DECISION. 2. FY2019 Clean Water Fund Implementation Program Policy and the FY2019 Clean Water Fund Competitive Grants Program Authorization – The purpose of this agenda items is to allocate FY19 Clean Water Competitive grants. On June 19, 2018 the Board adopted Board Order #18-33 which authorized staff to conduct a request for proposals from eligible local governments for Clean Water Fund projects in three program categories: Accelerated Implementation, Projects and Practices, and Multipurpose Drainage. Applications were accepted from July 9 through August 31, 2018. Local governments submitted 136 applications requesting $29,832,685 in Clean Water Funds. -

Surface Water Classifications

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. May 5, 2020 Surface Water Classifications Effective March 3, 2020 The following WQS document is in effect for Clean Water Act purposes with the exception some waterbodies. This revised document denotes EPA's previously approved/disapproved and reserved actions from: May 22, 2009, November 24, 2009, June 29, 2010, August 19, 2010, November 19, 2010, January 18, 2011, January 5, 2012, December 14, 2015, July 18, 2016, November 22, 2019 and March 3, 2020. Disapprovals are marked in red Reserved actions are marked in light blue Approvals in bright green This revised document denotes EPA's previously approved/disapproved and reserved actions from: May 22, 2009, November 24, 2009, June 29, 2010, August 19, 2010, November 19, 2010, January 18, 2011, January 5, 2012, December 14, 2015, July 18, 2016, November 22, 2019 and March 3, 2020. Disapprovals are marked in Red Reserved actions are marked in light blue Approvals in bright green SURFACE WATER CLASSIFICATION Prepared by: Water Quality Monitoring and Assessment Water Quality Bureau Environmental Services Division July 24, 2019 Iowa Department of Natural Resources Surface Water Classification A. Key to the order of streams. (1) Streams are listed in downstream to upstream sequence within a basin. -

Rock River Watershed Biotic Stressor Identification Report

Rock River Watershed Biotic Stressor Identification Report April 2015 Authors Michael Koschak Contributors / acknowledgements Chandra Carter Chuck Regan Mark Hanson Brooke Hacker Paul Marston Colton Cummings Katherine Pekarek-Scott Tim Larson Cover photo: Top: Rock River at site 11MS001, Lower Right: North Branch Chanarambie Creek at site 11MS123, Lower Left: Unnamed Creek at site 11MS096 Project dollars provided by the Clean Water Fund (From the Clean Water, Land and Legacy Amendment) Minnesota Pollution Control Agency 520 Lafayette Road North | Saint Paul, MN 55155-4194 | www.pca.state.mn.us | 651-296-6300 Toll free 800-657-3864 | TTY 651-282-5332 This report is available in alternative formats upon request, and online at www.pca.state.mn.us Document number: wq-ws5-10170204a Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................................6 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................9 Monitoring and assessment ................................................................................................................. 9 Stressor identification process ............................................................................................................ 10 Common stream stressors .................................................................................................................. 10 Report format .................................................................................................................................. -

Gazetteer of Surface Waters of Iowa

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIREin:OR ' WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 345-1 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS OF IOWA BY w. G. HOYT AND H. J. RYAN Contributions to the Hydrology of the United States, 1914-I WASHINGTON. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFIOE 1915 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS OF lOWA. By W. G. HoYT and H. J. RYAN. This gazetteer embraces descriptions of all the streams named on the best available maps of Iowa, including the United States Geo logical Survey's base map of Iowa (scale 1 to 500,000), county maps published in the annual report of 'the Iowa Geological Survey, and the topographic atlas sheets of the United States Geological Survey. Each stream is described as rising near the point at which its beginning is shown on the map. This method does not give results of great precision, and all statements of length and course are merely approximate. The letter Lor R, in parentheses after the name of a stream, indi cates that the stream is tributary from the left or right, respectively, to the stream into which it flows . .Abby Creek (L); Linn County; rises in T. 83 N., R. 5 W.; flows west 9 miles into Big Creek (tributary through Cedar River to Iowa River and thus to the Missis sippi) in Linn County, T. 83 N., R. 6 W . .Ackley Creek (R); Floyd County; rises in T. 94 N., R. 18 W.; flows east 9 miles into Shellrock River (tributary through Cedar River to Iowa River and thus to the Mississippi) in Floyd County, T.