NOBLES LOCAL WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN a 10-Year Plan with a 5-Year Implementation Schedule 2009-2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of Minnesota Department of Natural Resources

STATE OF MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Pursuant to Minnesota Statutes, Section 105.391, Subd. 1, the Commissioner of Natural Resources hereby publishes the final inventory of Protected (i.e. Public) Waters and Wetlands for Nobles County. This list is to be used in conjunction with the Protected Waters and Wetlands Map prepared for Nobles County. Copies of the final map and list are available for inspection at the following state and county offices: DNR Regional Office, New Ulm DNR Area Office, Marshall Nobles SWCD Nobles County Auditor Dated: STATE OF MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES JOSEPH N. ALEXANDER, Commissioner DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF WATERS FINAL DESIGNATION OF PROTECTED WATERS AND WETLANDS WITHIN NOBLES COUNTY, MINNESOTA. A. Listed below are the townships of Nobles County and the township/range numbers in which they occur. Township Name Township # Range # Bigelow 101 40 Bloom 104 41 Dewald 102 41 Elk 103 40 Graham Lakes 104 39 Grand Prairie 101 43 Hersey 103 39 Indian Lake 101 39 Larkin 103 42 Leota 104 43 Lismore 103 43 Little Rock 101 42 Lorain 102 39 Olney 102 42 Ransom 101 41 Seward 104 40 Summit Lake 103 41 Westside 102 43 Wilmont 104 42 Worthington 102 40 B. PROTECTED WATERS 1. The following are protected waters: Number and Name Section Township Range 53-7 : Indian Lake 27,34 101 39 53-9 : Maroney(Woolsten- 32 102 39 croft) Slough 53-16 : Kinbrae Lake (Clear) 11 104 39 Page 1 Number and Name Section Township Range 53-18 : Kinbrae Slough 11,14 104 39 53-19 : Jack Lake 14,15 104 39 53-20 : East Graham Lake 14,22,23,26,27 104 39 53-21 : West Graham Lake 15,16,21,22 104 39 53-22 : Fury Marsh 22 104 39 53-24 : Ocheda Lake various 101;102 39;40 53-26 : Peterson Slough 21,22 101 40 53-27 : Wachter Marsh 23 101 40 53-28 : Okabena Lake 22,23,26,27,28 102 40 53-31 : Sieverding Marsh 2 104 40 53-32 : Bigelow Slough NE 36 101 41 53-33 : Boote-Herlein Marsh 6,7;1,12 102 40;41 53-37 : Groth Marsh NW 2 103 41 53-45 : Bella Lake 26,27,34 101 40 *32-84 : Iowa Lake 31;36 101 38;39 *51-48 : Willow Lake 5;33 104;105 41 2. -

Chapter 7050 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Water Quality Division Waters of the State

MINNESOTA RULES 1989 6711 WATERS OF THE STATE 7050.0130 CHAPTER 7050 MINNESOTA POLLUTION CONTROL AGENCY WATER QUALITY DIVISION WATERS OF THE STATE STANDARDS FOR THE PROTECTION OF THE 7050.0214 REQUIREMENTS FOR POINT QUALITY AND PURITY OF THE WATERS OF SOURCE DISCHARGERS TO THE STATE LIMITED RESOURCE VALUE 7050.0110 SCOPE. WATERS. 7050.0130 DEFINITIONS. 7050.0215 REQUIREMENTS FOR ANIMAL 7050.0140 USES OF WATERS OF THE STATE. FEEDLOTS. 7050.0150 DETERMINATION OF 7050.0220 SPECIFIC STANDARDS OF COMPLIANCE. QUALITY AND PURITY FOR 7050.0170 NATURAL WATER QUALITY. DESIGNATED CLASSES OF 7050.0180 NONDEGRADATION FOR WATERS OF THE STATE. OUTSTANDING RESOURCE CLASSIFICATIONS OF WATERS OF THE VALUE WATERS. STATE 7050.0185 NONDEGRADATION FOR ALL 7050.0400 PURPOSE. WATERS. 7050.0410 LISTED WATERS. 7050.0190 VARIANCE FROM STANDARDS. 7050.0420 TROUT WATERS. 7050.0200 WATER USE CLASSIFICATIONS 7050.0430 UNLISTED WATERS. FOR WATERS OF THE STATE. 7050.0440 OTHER CLASSIFICATIONS 7050.0210 GENERAL STANDARDS FOR SUPERSEDED. DISCHARGERS TO WATERS OF 7050.0450 MULTI-CLASSIFICATIONS. THE STATE. 7050.0460 WATERS SPECIFICALLY 7050.0211 FACILITY STANDARDS. CLASSIFIED. 7050.0212 REQUIREMENTS FOR POINT 7050.0465 MAP: MAJOR SURFACE WATER SOURCE DISCHARGERS OF DRAINAGE BASINS. INDUSTRIAL OR OTHER WASTES. 7050.0470 CLASSIFICATIONS FOR WATERS 7050.0213 ADVANCED WASTEWATER IN MAJOR SURFACE WATER TREATMENT REQUIREMENTS. DRAINAGE BASINS. 7050.0100 [Repealed, 9 SR 913] STANDARDS FOR THE PROTECTION OF THE QUALITY AND PURITY OF THE WATERS OF THE STATE 7050.0110 SCOPE. Parts 7050.0130 to 7050.0220 apply to all waters of the state, both surface and underground, and include general provisions applicable to the maintenance of water quality and aquatic habitats; definitions of water use classes; standards for dischargers of sewage, industrial, and other wastes; and standards of quality and purity for specific water use classes. -

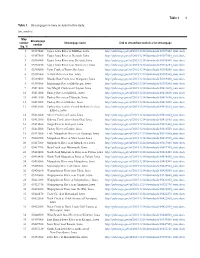

Statistical Summaries of Selected Iowa Streamflow Data--Table 1

Table 1 1 Table 1. Streamgages in Iowa included in this study. [no., number] Map Streamgage number Streamgage name Link to streamflow statistics for streamgage number (fig. 1) 1 05387440 Upper Iowa River at Bluffton, Iowa http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2015/1214/downloads/05387440_stats.docx 2 05387500 Upper Iowa River at Decorah, Iowa http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2015/1214/downloads/05387500_stats.docx 3 05388000 Upper Iowa River near Decorah, Iowa http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2015/1214/downloads/05388000_stats.docx 4 05388250 Upper Iowa River near Dorchester, Iowa http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2015/1214/downloads/05388250_stats.docx 5 05388500 Paint Creek at Waterville, Iowa http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2015/1214/downloads/05388500_stats.docx 6 05389000 Yellow River near Ion, Iowa http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2015/1214/downloads/05389000_stats.docx 7 05389400 Bloody Run Creek near Marquette, Iowa http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2015/1214/downloads/05389400_stats.docx 8 05389500 Mississippi River at McGregor, Iowa http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2015/1214/downloads/05389500_stats.docx 9 05411400 Sny Magill Creek near Clayton, Iowa http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2015/1214/downloads/05411400_stats.docx 10 05411600 Turkey River at Spillville, Iowa http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2015/1214/downloads/05411600_stats.docx 11 05411850 Turkey River near Eldorado, Iowa http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2015/1214/downloads/05411850_stats.docx 12 05412000 Turkey River at Elkader, Iowa http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2015/1214/downloads/05412000_stats.docx 13 05412020 Turkey River above French Hollow Creek at http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2015/1214/downloads/05412020_stats.docx -

Little Sioux River Watershed Biotic Stressor Identification Report

Little Sioux River Watershed Biotic Stressor Identification Report April 2015 Authors Editing and Graphic Design Paul Marston Sherry Mottonen Jennifer Holstad Contributors/acknowledgements Michael Koschak Kim Laing The MPCA is reducing printing and mailing costs by Chandra Carter using the Internet to distribute reports and Chuck Regan information to wider audience. Visit our website Mark Hanson for more information. Katherine Pekarek-Scott MPCA reports are printed on 100% post-consumer Colton Cummings recycled content paper manufactured without Tim Larson chlorine or chlorine derivatives. Chessa Frahm Brooke Hacker Jon Lore Cover photo: Clockwise from Top Left: Little Sioux River at site 11MS010; County Ditch 11 at site 11MS078; Cattle around Unnamed Creek at site 11MS067 Project dollars provided by the Clean Water Fund (From the Clean Water, Land and Legacy Amendment) Minnesota Pollution Control Agency 520 Lafayette Road North | Saint Paul, MN 55155-4194 | www.pca.state.mn.us | 651-296-6300 Toll free 800-657-3864 | TTY 651-282-5332 This report is available in alternative formats upon request, and online at www.pca.state.mn.us Document number: wq-ws5-10230003a Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 2 Monitoring and assessment ...........................................................................................................2 -

Up the Minnesota Valley to Fort Ridgely in 1853

MINNESOTA AS SEEN BY TRAVELERS UP THE MINNESOTA VALLEY TO FORT RIDGELY IN 1853 The treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota in the summer of 1851 greatly simplified the problem of providing homes for the thousands of immigrants who were flocking to Minnesota Territory. Prior to that date legal settlement had been confined to the region east of the Mississippi below the mouth of the Crow Wing River, but as James M. Goodhue, the editor of the Minnesota Pioneer, wrote in the issue for August 16, 1849, " These Sioux lands [west of the Missis sippi] are the admiration of every body, and the mouth of many a stranger and citizen waters while he looks beyond the Mississippi's flood upon the fair Canaan beyond." Small wonder, then, that Governor Alexander Ramsey worked for a treaty that would open these lands to white settlement. There was much opposition to the treaties in the Senate dur ing the spring of 1852, and they were not ratified until June 23 of that year. Henry H. Sibley, the territorial delegate in Congress, wrote to Ramsey that " never did any measures have a tighter squeeze through."^ Even after they were ratified, the eager settlers legally should have waited until the Indians could be removed and surveys made by the general land office. The land speculator and the settler, however, were not to be balked by such minor details as the presence of Indians and the lack of surveys. They went into the region before it was legally open to settlement and some even planted crops. -

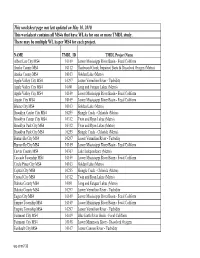

List of Impaired Waters & Tmdls-Regulated Ms4s

This worksheet page was last updated on May 10, 2010. This worksheet contains all MS4s that have WLAs for one or more TMDL study. There may be multiple WLAs per MS4 for each project. NAME TMDL_ID TMDL Project Name Albert Lea City MS4 10169 Lower Mississippi River Basin - Fecal Coliform Anoka County MS4 10112 Hardwood Creek, Impaired Biota & Dissolved Oxygen (Metro) Anoka County MS4 10103 Golden Lake (Metro) Apple Valley City MS4 10297 Lower Vermilion River - Turbidity Apple Valley City MS4 10091 Long and Farquar Lakes (Metro) Apple Valley City MS4 10169 Lower Mississippi River Basin - Fecal Coliform Austin City MS4 10169 Lower Mississippi River Basin - Fecal Coliform Blaine City MS4 10103 Golden Lake (Metro) Brooklyn Center City MS4 10255 Shingle Creek - Chloride (Metro) Brooklyn Center City MS4 10312 Twin and Ryan Lakes (Metro) Brooklyn Park City MS4 10312 Twin and Ryan Lakes (Metro) Brooklyn Park City MS4 10255 Shingle Creek - Chloride (Metro) Burnsville City MS4 10297 Lower Vermilion River - Turbidity BurnsvilleBurnsville Cit Cityy MS4 10169 LowerLower Mi Mississippississippi RiverRiver BasinBasin - FecalFecal C Coliformoliform Carver County MS4 10367 Lake Independence (Metro) Cascade Township MS4 10169 Lower Mississippi River Basin - Fecal Coliform Circle Pines City MS4 10103 Golden Lake (Metro) Crystal City MS4 10255 Shingle Creek - Chloride (Metro) Crystal City MS4 10312 Twin and Ryan Lakes (Metro) Dakota County MS4 10091 Long and Farquar Lakes (Metro) Dakota County MS4 10297 Lower Vermilion River - Turbidity Eagan City MS4 10169 Lower Mississippi River Basin - Fecal Coliform Empire Township MS4 10169 Lower Mississippi River Basin - Fecal Coliform Empire Township MS4 10297 Lower Vermilion River - Turbidity Fairmont City MS4 10019 Blue Earth River Basin - Fecal Coliform Fairmont City MS4 10168 Lower Minnesota River - Dissolved Oxygen Faribault City MS4 10167 Lower Cannon River - Turbidity wq-strm7-33 This worksheet page was last updated on May 10, 2010. -

Stagecoach State Trail Master Plan Section 6

Section 6: Cultural and Socioeconomic Resources Stagecoach State Trail Master Plan Section 6: Cultural and Socioeconomic Resources The area around Rochester was home to nomadic Sioux, Ojibwa, and Winnebago tribes of Native Americans. In 1851, the Sioux ceded the land to Minnesota Territory in the treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota. In 1853, the treaties were concluded, opening the land for settlement. Since the time of early European settlement, people have been finding evidence of earlier human activity in the vicinity of Rice Lake. This evidence includes stone tools and pottery fragments, which have been found in significant numbers near the lakeshore and in the agricultural fields surrounding the lake. With the signing of the treaty of Traverse des Sioux in 1851, the Dakota Indians ceded their land in western and southern Minnesota, including the Rice Lake area, to the United States Government. The Dakota were restricted to reservation lands bordering the Minnesota River from the Little Rock River near New Ulm to the Minnesota - South Dakota Border. The Rice Lake State Park Management Plan indicates that in 1972, an archaeological excavation was conducted in the park by staff and students from the University of Minnesota, Department of Anthropology. The major excavation site was on the east shore of the eastern arm of the lake, a few hundred yards north of the Zumbro River branch outflow. The excavation uncovered a number of stone implements and pottery fragments, as well as some fire pits. Preliminary analysis suggested that the materials represent several different time periods, possibly from as early as the Archaic period (5,000 – 1,000 B.C.) to early historic times. -

Ground Water in Alluvial Channel Deposits Nobles County, Minnesota

Bulletin No. 14 DIVISION OF WATERS MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION GROUND WATER IN ALLUVIAL CHANNEL DEPOSITS NOBLES COUNTY, MINNESOTA By Ralph F. Norvitch U. S. Geological Survey Prepared cooperatively by the Geological Survey, U. S. Department of the Interior and the Division of Waters, Minnesota Department of Conservation St. Paul, Minn. September 1960 1 CONTENTS Page Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..4 Geology……………………………………………………………………………………4 History of the valleys……………………………………………………………...5 Thickness of the alluvium…………………………………………………………7 Texture of the alluvium…………………………………………………………..10 Ground water conditions…………………………………………………………………11 Significant factors for locating wells…………………………………………………….13 Quality of water………………………………………………………………………….14 Conclusions………………………………………………………………………………14 References………………………………………………………………………………..15 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. Map of Nobles County, Minn., showing alluvial deposits, morainal fronts, auger holes, selected municipal wells, and the Missouri-Mississippi River divide …………………………………………16 2. Generalized cross section of Little Rock River valley, Nobles County………..9 TABLES Table 1. Data from auger holes bored in the alluvial deposits in Nobles County, Minn. ………………………………………….8 2. Summary of data from auger holes bored in the alluvial deposits in Nobles County………………………………………………………………………….10 2 GROUND WATER IN ALLUVIAL CHANNEL DEPOSITS NOBLES COUNTY, MINNESOTA By Ralph F. Norvitch ABSTRACT The alluvial channel deposits described in this report are in Nobles County, Minn., about 150 miles southwest of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Although four municipalities and many farms obtain part or all of their water needs from the alluvium, it has not yet been fully developed for ground water. The extent of the alluvial channel deposits was mapped on high-altitude aerial photographs, and a power auger was used to bore 43 test holes to determine the thickness of alluvium and the water level at each of the test sites. -

West Fork Des Moines River and Heron Lake TMDL Implementation Plan

West Fork Des Moines River and Heron Lake TMDL Implementation Plan September 2009 Submitted by: Heron Lake Watershed District In cooperation with the TMDL Advisory and Technical Committees Preface This implementation plan was written by the Heron Lake Watershed District (HLWD), with the assistance of the Advisory Committee, and Technical Committee, and guidance from the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) based on the report West Fork Des Moines River Watershed Total Maximum Daily Load Final Report: Excess Nutrients (North and South Heron Lake), Turbidity, and Fecal Coliform Bacteria Impairments. Advisory Committee and Technical Committee members that helped develop this plan are: Advisory Committee Karen Johansen City of Currie Jeff Like Taylor Co-op Clark Lingbeek Pheasants Forever Don Louwagie Minnesota Soybean Growers Rich Perrine Martin County SWCD Randy Schmitz City of Brewster Michael Hanson Cottonwood County Tom Kresko Minnesota Department of Natural Resources - Windom Technical Committee Kelli Daberkow Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Jan Voit Heron Lake Watershed District Ross Behrends Heron Lake Watershed District Melanie Raine Heron Lake Watershed District Wayne Smith Nobles County Gordon Olson Jackson County Chris Hansen Murray County Pam Flitter Martin County Roger Schroeder Lyon County Kyle Krier Pipestone County and Soil and Water Conservation District Ed Lenz Nobles Soil and Water Conservation District Brian Nyborg Jackson Soil and Water Conservation District Howard Konkol Murray Soil and Water Conservation District Kay Clark Cottonwood Soil and Water Conservation District Rose Anderson Lyon Soil and Water Conservation District Kathy Smith Martin Soil and Water Conservation District Steve Beckel City of Jackson Mike Haugen City of Windom Jason Rossow City of Lakefield Kevin Nelson City of Okabena Dwayne Haffield City of Worthington Bob Krebs Swift Brands, Inc. -

Water Quality Trends at Minnesota Milestone Sites

Water Quality Trends for Minnesota Rivers and Streams at Milestone Sites Five of seven pollutants better, two getting worse June 2014 Author The MPCA is reducing printing and mailing costs by using the Internet to distribute reports and David Christopherson information to wider audience. Visit our website for more information. MPCA reports are printed on 100% post- consumer recycled content paper manufactured without chlorine or chlorine derivatives. Minnesota Pollution Control Agency 520 Lafayette Road North | Saint Paul, MN 55155-4194 | www.pca.state.mn.us | 651-296-6300 Toll free 800-657-3864 | TTY 651-282-5332 This report is available in alternative formats upon request, and online at www.pca.state.mn.us . Document number: wq-s1-71 1 Summary Long-term trend analysis of seven different water pollutants measured at 80 locations across Minnesota for more than 30 years shows consistent reductions in five pollutants, but consistent increases in two pollutants. Concentrations of total suspended solids, phosphorus, ammonia, biochemical oxygen demand, and bacteria have significantly decreased, but nitrate and chloride concentrations have risen, according to data from the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency’s (MPCA) “Milestone” monitoring network. Recent, shorter-term trends are consistent with this pattern, but are less pronounced. Pollutant concentrations show distinct regional differences, with a general pattern across the state of lower levels in the northeast to higher levels in the southwest. These trends reflect both the successes of cleaning up municipal and industrial pollutant discharges during this period, and the continuing challenge of controlling the more diffuse “nonpoint” polluted runoff sources and the impacts of increased water volumes from artificial drainage practices. -

Des Moines… Model Report

Des Moines Headwaters, Lower Des Moines, and East Fork Des Moines River Basins Watershed Model Development) Prepared for Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Prepared by One Park Drive, Suite 200 • PO Box 14409 Research Triangle Park, NC 27709 June 27, 2016 wq-ws4-52c (This page left intentionally blank.) Des Moines River Watershed Model Report June 28, 2016 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................1 2 Watershed Model Development ...................................................................................5 2.1 Upland Representation ......................................................................................................................5 Geology, Soils, and Slopes ........................................................................................................5 Land Use and Land Cover .........................................................................................................9 Development of HRUs ............................................................................................................. 12 2.2 Meteorology .................................................................................................................................... 15 Data Processing ....................................................................................................................... 15 Auxiliary Weather Series ........................................................................................................ -

External Station ID Schemes May 29, 2008 10:52:57 1117MBR US EPA Region 7 Acronym External Reference Scheme Name Description

External Station ID Schemes May 29, 2008 10:52:57 1117MBR US EPA Region 7 Acronym External Reference Scheme Name Description IDNR Iowa Dept of Natural Resources site ID KDHE Kansas Dept of Health & Environment site ID MDNR Missouri Dept of Natural Resources site ID NDEQ Nebraska Dept of Environmental Quality site ID NPDES National Pollution Discharge Elimination System SECNUMS Legacy Storet Secondary Station IDs Secondary Station Numbers MIGRATED FROM LEGACY STORET ON 13-DEC-99 USGS U S Geologic Survey Station Number Page 1 of 67 External Station ID Schemes May 29, 2008 10:52:57 1119USBR Bureau of Reclamation Acronym External Reference Scheme Name Description SECNUMS Legacy Storet Secondary Station IDs Secondary Station Numbers MIGRATED FROM LEGACY STORET ON 05-FEB-00 Page 2 of 67 External Station ID Schemes May 29, 2008 10:52:57 11DELMOD Delaware River Basin Commission Acronym External Reference Scheme Name Description LOWDEL Lower Delaware Monitoring Program NAWQA USGS National Water Quality Assessment - Delaware River Page 3 of 67 External Station ID Schemes May 29, 2008 10:52:57 11NPSWRD National Park Service Acronym External Reference Scheme Name Description HORIZON Baseline Water Quality Data Inventory and Analysis Baseline Water Quality Data Inventory and Analysis "Horizon" Report assigned Station ID Report sequence value. Note: Some parks (e.g. OZAR) may have continued the ID convention (i.e. OZAR0147) for stations that didn't appear in the Horizon Report. SECSTA1 First Station Alias/Name/ID from Legacy STORET SECSTA2 Second Station Alias/Name/ID from Legacy STORET SECSTA3 Third Station Alias/Name/ID from Legacy STORET Page 4 of 67 External Station ID Schemes May 29, 2008 10:52:57 211WVOWR Division of Water and Waste Management Acronym External Reference Scheme Name Description WAPBASE Watershed Assesment Program Data Base Page 5 of 67 External Station ID Schemes May 29, 2008 10:52:57 21COL001 Colorado Dept.