How the Electoral College Imitates the World Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ticket Stubs Alone Have Little Value

Ticket stubs alone have little value Jeff Figler can be reached at [email protected]. He would be glad to give you his opinion on values of sports collectibles. BY JEFF FIGLER SPECIAL TO THE POST-DISPATCH 02/17/2010 Every so often I am asked if there is value to ticket stubs, or even unused full tickets. In short, the answer is no. The only instances in which ticket stubs or unused tickets are of value is if they are related to significant events, and only if they are auctioned with other related items. A ticket stub to, let's say a game in July 1962 has no value, except to the owner of the stub. (Maybe going to the game was a birthday gift.) However, a ticket stub to a game of historical significance, for example, Game 7 of the 1960 World Series between the New York Yankees and the Pittsburgh Pirates, would have some value. If you combine the ticket stub from that game, with a program from that game, newspaper clippings, and a team-signed ball of the 1960 Pirates, then you have a nice package, worth a minimum of $500. Of course, the value will depend on the condition of the items, especially of the baseball, and if there happened to be a bidding war on that lot. In case you might have forgotten, Game 7 of the 1960 World Series was the one in which statistically the Yankees dominated, but the Bucs won the Series on a walk-off homer by Bill Mazeroski. If someone has the entire unused ticket of a particular event, not merely the ticket stub, the value goes up a bit, but not dramatically. -

Reign Men Taps Into a Compelling Oral History of Game 7 in the 2016 World Series

Reign Men taps into a compelling oral history of Game 7 in the 2016 World Series. Talking Cubs heads all top CSN Chicago producers need in riveting ‘Reign Men’ By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Thursday, March 23, 2017 Some of the most riveting TV can be a bunch of talking heads. The best example is enjoying multiple airings on CSN Chicago, the first at 9:30 p.m. Monday, March 27. When a one-hour documentary combines Theo Epstein and his Merry Men of Wrigley Field, who can talk as good a game as they play, with the video skills of world-class producers Sarah Lauch and Ryan McGuffey, you have a must-watch production. We all know “what” happened in the Game 7 Cubs victory of the 2016 World Series that turned from potentially the most catastrophic loss in franchise history into its most memorable triumph in just a few minutes in Cleveland. Now, thanks to the sublime re- porting and editing skills of Lauch and McGuffey, we now have the “how” and “why” through the oral history contained in “Reign Men: The Story Behind Game 7 of the 2016 World Series.” Anyone with sense is tired of the endless shots of the 35-and-under bar crowd whooping it up for top sports events. The word here is gratuitous. “Reign Men” largely eschews those images and other “color” shots in favor of telling the story. And what a tale to tell. Lauch and McGuffey, who have a combined 20 sports Emmy Awards in hand for their labors, could have simply done a rehash of what many term the greatest Game 7 in World Series history. -

Impartial Arbiter, New Hall of Famer O'day Was Slanted to Chicago in Personal Life

Impartial arbiter, new Hall of Famer O’Day was slanted to Chicago in personal life By George Castle, CBM historian Monday, Dec. 17 For a man who wore an impenetrable mask of reserve behind his umpire’s headgear, Hank O’Day sure wore his heart on his sleeve when it came to his native Chicago. O’Day was serious he only allowed his few close friends to call him “Hank.” He was “Henry” to most others in his baseball trav- els as one of the greatest arbiters ever. But in a Chicago he never left as home, he could be himself. Born July 8, 1862 in Chicago as one of six children of deaf parents, O’Day always came back home and lived out his life in the Sec- ond City. He died July 2, 1935 in Chicago, and was buried in the lakefront Calvary Cemetery, just beyond the north city limits in Evanston. In between, he first played Hank O'Day in civilian clothes baseball competitively on the city’s sandlots as Cubs manager in 1914. with none other than Charles Comiskey, the founding owner of the White Sox. And in taking one of a pair of season-long breaks to manage a big-league team amid his three-decade umpiring career, O’Day was Cubs manager in 1914, two years after he piloted the Cincinnati Reds for one year. Through all of that, his greatest connection to his hometown was one of the most fa- mous calls in baseball history – the “out” ruling at second base on New York Giants rookie Fred Merkle in a play that led to the last Cubs World Series title in 1908. -

PDF of August 17 Results

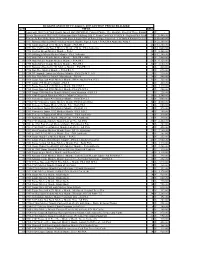

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

Rademacher Dream Ended, Hr Vjwhwl

CLASSIFIED ADS, Pages C-6-14 C IMMHMMHHH W)t fining sHaf SPORTS WASHINGTON, D. C., FRIDAY, AUGUST 23, 1957 kk . Y^k Rademacher Dream Ended, Hr VjwHwl , . ¦ ¦ |f But He Gave It a Good Try , */ Patterson Wins by KO in 6 - LoughranSays • / . a- '•* %>¦ ' Injury ' •%* ,%¦ :&# :? .. V\fefit#%. ;; *• Musial'* ; .: *., : *£>• ':-:->\ :, ', ¦ k- ..::s. .. -.<• tl> Sg| **&(<.¦¦¦¦• ¦m& ?:sWW*fc WMW•-•••- W'?r***Y:J;'*•':. :*.V« t:s' : . :t: ', • >,- . *.£;* ' ?• . •;'-^ Being r ’v. x ; c.s-\ .*¦ Loser Should After Down Himself SEATTLE, Aug. 23 TP).—Floyd Patterson, the cool de- IgF Cripples Cards Up Ring stroyer who holds the world heavyweight championship, cut Give down powerful Pete Rademacher last night and ended A — SEATTLE, Aug. 23 (A*). the big ex-football player’s dream of stepping from the SB • Bp SsE . K» Referee Loughran, Tommy one amateur peak to the pinnacle of the pros. For 10 Days of the great light-heavyweight away pounds—the champion weighed champions of yesteryear, today Giving 15 187 to By the Associated Press advised Pete Rademacher to Rademacher’s 202 Floyd " The pennant hopes of the quit the ring. decked the courageous chal- . and hurt, and the few blows he St. Louis Cardinals were hand- At the same time he said lenger seven times at Sick’s ] landed in the sixth lacked sting. ed a devastating blow today Floyd Patterson could become Stadium before Pete took the ; He clinched and, as Loughran when Stan Musial learned that as great a heavyweight cham- full count at 2:57 of the sixth i moved in to separate them Pat- he will be out of action for 10 pion as Jack Dempsey. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Official Game Information

Official Game Information Yankee Stadium • One East 161st Street • Bronx, NY 10451 Media Relations Phone: (718) 579-4460 • [email protected] • Twitter: @yankeespr YANKEES BY THE NUMBERS NOTE 2012 (Postseason) 2012 AMERICAN LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES – GAME 1 Home Record: . 51-30 (2-1) NEW YORK YANKEES (3-2/95-67) vs. DETROIT TIGERS (3-2/88-74) Road Record: . 44-37 (1-1) Day Record: . .. 32-20 (---) LHP ANDY PETTITTE (0-1, 3.86) VS. RHP DOUG FISTER (0-0, 2.57) Night Record: . 63-47 (3-2) Saturday, OctOber 13 • 8:07 p.m. et • tbS • yankee Stadium vs . AL East . 41-31 (3-2) vs . AL Central . 21-16 (---) vs . AL West . 20-15 (---) AT A GLANCE: The Yankees will play Game 1 of the 2012 American League Championship Series vs . the Detroit Tigers tonight at Yankee Stadium…marks the Yankees’ 15th ALCS YANKEES IN THE ALCS vs . National League . 13-5 (---) (Home Games in Bold) vs . RH starters . 58-43 (3-0) all-time, going 11-3 in the series, including a 7-2 mark in their last nine since 1996 – which vs . LH starters . 37-24 (0-2) have been a “best of seven” format…is their third ALCS in five years under Joe Girardi (also YEAR OPP W L Detail Yankees Score First: . 59-27 (2-1) 2009 and ‘10)…are 34-14 in 48 “best-of-seven” series all time . 1976** . KC . 3 . 2 . WLWLW Opp . Score First: . 36-40 (1-1) This series is a rematch of the 2011 ALDS, which the Tigers won in five games . -

Giants and Dodgers Also Triumph Shawkey Collapsesin Ninth

Ruth's Twentieth Home Run Wins for Yankees . Giants and Dodgers Also Triumph in Ninth Shawkey Collapses Ain't It a Grand and Glorious Feelin'? By BRIGGS Yale Doubles After Pitching Brilliantly Copyright, 1020, New York Tribune Inc. Harvard Tally In Ouiiiii (¿ors to Rescue of Bob the -Gob; Shocker, véneto, As a travelling ANiD ALL KINDS OF v? -AMD You ARE PLAYW6 /NJ Second Game MAtO YOU HAVE HAß To P^T DISCOMFORT US) HARD Old Jinx of Is Hit in Pinehes -RAILROADS LUCK IM G6TTirJ<S Hugmen, Freely (JP IAJITH FIERCE HOTF/L ^_^_^_.y .,,,,-/,,._ orders fron-% Buyers Coxe Outpitches Goode and and Is Compelled to Give Way to Van Gilder A. CC 0 r*A otDaTI 0 NJ 5 Elis Tie the Annual Se¬ ries by Winning, 4 to 2 flpnHal DUratrh to Th* Tribun* - ST. LOUIS, June 2."..--The Yankees brought their Western trip to a KIN GivE \ From a ¡Special Correspondent r'o.-e to-day with a 6 to 3 victory over the Browns. "Babe" Ruth hit his WûO A COT OR ) CAMBRIDGE, Mass., June 23.-Yale evened the twentieth home run of the season, and Urban Shocker, pitching for the« YEH KIN r-.7 up series with Harvard this . x afternoon 4 to on Sol- Browns, was batted out %i the box for the second time during the series, DOUBLE ÜPy.í/1 by winning, 2, r / diers' Field, before a commencement lx\ the ninth Bob Shawkey, to Austin, suddenly crumpled U)lTH A inning pitching MAMsi fa ^-¡j week crowd of 15,000. -

BASEBALL DIGEST: 48 the Game I’Ll Never Forget 2016 Preview Issue by Billy Williams As Told to Barry Rozner Hall of Famer Recalls Opening Day Walk-Off Homer

CONTENTS January/February 2016 — Volume 75. No. 1 FEATURES 9 Warmup Tosses by Bob Kuenster Royals Personified Spirit of Winning in 2015 12 2015 All-Star Rookie Team by Mike Berardino MLB’s top first-year players by position 16 Jake Arrieta: Pitcher of the Year by Patrick Mooney Cubs starter raised his performance level with Cy Young season 20 Bryce Harper: Player of the Year by T.R. Sullivan MVP year is only the beginning for young star 24 Kris Bryant: Rookie of the Year by Bruce Levine Cubs third baseman displayed impressive all-around talent in debut season 30 Mark Melancon: Reliever of the Year by Tom Singer Pirates closer often made it look easy finishing games 34 Prince Fielder: Comeback Player of the Year by T.R. Sullivan Slugger had productive season after serious injury 38 Farewell To Yogi Berra by Marty Appel Yankee legend was more than a Hall of Fame catcher MANNY MACHADO Orioles young third 44 Strikeouts on the Rise by Thom Henninger baseman is among the game’s elite stars, page 52. Despite many changes to the game over the decades, one constant is that strikeouts continue to climb COMING IN BASEBALL DIGEST: 48 The Game I’ll Never Forget 2016 Preview Issue by Billy Williams as told to Barry Rozner Hall of Famer recalls Opening Day walk-off homer 52 Another Step To Stardom by Tom Worgo Manny Machado continues to excel 59 Baseball Profile by Rick Sorci Center fielder Adam Jones DEPARTMENTS 4 Baseball Stat Corner 6 The Fans Speak Out 28 Baseball Quick Quiz SportPics Cover Photo Credits by Rich Marazzi Kris Bryant and Carlos Correa 56 Baseball Rules Corner by SportPics 58 Baseball Crossword Puzzle by Larry Humber 60 7th Inning Stretch January/February 2016 3 BASEBALL STAT CORNER 2015 MLB AWARD WINNERS CARLOS CORREA SportPics (Top Five Vote-Getters) ROOKIE OF THE YEAR AWARD AMERICAN LEAGUE Player, Team Pos. -

Basic Template

Every month I summarize the most important probate cases in Michigan. Now I publish my summaries as a service to colleagues and friends. I hope you find these summaries useful and I am always interested in hearing thoughts and opinions on these cases. PROBATE LAW CASE SUMMARY BY: Alan A. May Alan May is a shareholder who is sought after for his experience in guardianships, conservatorships, trusts, wills, forensic probate issues and probate. He has written, published and lectured extensively on these topics. He was selected for inclusion in the 2007-2017, 2019 issues of Michigan Super Lawyers magazine featuring the top 5% of attorneys in Michigan and has been called by courts as an expert witness on issues of fees and by both plaintiffs and defendants as an expert witness in the area of probate and trust law. Mr. May maintains an “AV” peer review rating with Martindale-Hubbell Law Directory, the highest peer review rating for attorneys and he is listed in the area of Probate Law among Martindale-Hubbell’s Preeminent Lawyers. He has also been selected by his peers for inclusion in The Best Lawyers in America® 2020 in the fields of Trusts and Estates as well as Litigation – Trusts & Estates (Copyright 2018 by Woodward/White, Inc., of SC). He has been included in the Best Lawyers listing since 2011. Additionally, Mr. May was selected by a vote of his peers to be included in DBusiness magazine’s list of 2017 Top Lawyers in the practice area of Trusts and Estates. Kemp Klein is a member of LEGUS a global network of prominent law firms. -

Team History

PITTSBURGH PIRATES TEAM HISTORY ORGANIZATION Forbes Field, Opening Day 1909 The fortunes of the Pirates turned in 1900 when the National 2019 PIRATES 2019 THE EARLY YEARS League reduced its membership from 12 to eight teams. As part of the move, Barney Dreyfuss, owner of the defunct Louisville Now in their 132nd National League season, the Pittsburgh club, ac quired controlling interest of the Pirates. In the largest Pirates own a history filled with World Championships, player transaction in Pirates history, the Hall-of-Fame owner legendary players and some of baseball’s most dramatic games brought 14 players with him from the Louisville roster, including and moments. Hall of Famers Honus Wag ner, Fred Clarke and Rube Waddell — plus standouts Deacon Phillippe, Chief Zimmer, Claude The Pirates’ roots in Pittsburgh actually date back to April 15, Ritchey and Tommy Leach. All would play significant roles as 1876, when the Pittsburgh Alleghenys brought professional the Pirates became the league’s dominant franchise, winning baseball to the city by playing their first game at Union Park. pennants in 1901, 1902 and 1903 and a World championship in In 1877, the Alleghenys were accepted into the minor-league 1909. BASEBALL OPS BASEBALL International Association, but disbanded the following year. Wagner, dubbed ‘’The Fly ing Dutchman,’’ was the game’s premier player during the decade, winning seven batting Baseball returned to Pittsburgh for good in 1882 when the titles and leading the majors in hits (1,850) and RBI (956) Alleghenys reformed and joined the American Association, a from 1900-1909. One of the pioneers of the game, Dreyfuss is rival of the National League. -

Complete Tape Subject

-1- NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM Tape Subject Log (rev. Oct.-08) Conversation No. 832-1 Date: January 3, 1973 Time: Unknown between 3:32 pm and 3:39 pm Location: Oval Office The President met with Curtis C. Stapp, Mrs. Curtis Stapp, Donna Stapp, and Donald F. Rodgers. The White House photographer and members of the press were present at the beginning of the meeting. Greetings Congratulations Sports -California Photograph session -Arrangements -Copies -Press 1973 "Driver of the Year" award -Truck driving -The President’s driving -Secret Service -Courteous driving -Physical examinations -Union -Company Rose Garden -Tricia Nixon Cox’s wedding location -Television [TV] Meeting with the President -Appreciation -2- NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM Tape Subject Log (rev. Oct.-08) Conversation No. 832-1 (cont’d) Rodgers Frank E. Fitzsimmons -Golf -International Brotherhood of Teamsters -Support for the President Stapp, et al., left at 3:39 pm. Conversation No. 832-2 Date: January 3, 1973 Time: Unknown between 3:39 pm and 3:43 pm Location: Oval Office The President met with Stephen B. Bull. The President's schedule -Richard A. Moore -Willie Stargell -Stephen Blass -Truck drivers Bull left at an unknown time before 3:43 pm. Conversation No. 832-3 Date: January 3, 1973 Time: Unknown between 3:39 pm and 3:43 pm Location: Oval Office The President met with Stephen B. Bull. Arrangements for meeting -Daniel M. Galbreath -Baseball players -3- NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM Tape Subject Log (rev. Oct.-08) Conversation No. 832-3 (cont’d) Bull left at an unknown time before 3:43 pm.