To Whomsoever It May Concern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amol and Chitra Palekar

NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN Interview of Amol and ChitraPalekar FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF NATYASHODHSANSTHAN AUDIO LIBRARY Recorded on 1st. July, 1982 NatyaBhavan EE 8, Sector 2, Salt Lake, Kolkata 700091/ Call 033 23217667 visit us at http://www.natyashodh.org https://sites.google.com/view/nssheritagelibrary/home (Amol Palekar&ChitraPalekar came a little late and joined the discussionregarding the scope of theatre and the different forms a playwright tries to explore.) ChitraPalekar It is not that you cannot do a thing. You can do anything, you can do anything. It is not the point. The point is that the basic advantage that cinema has over theatre, the whole mass of audience, you know, all those eight hundred or nine hundred people he can put them to a close-up. This tableau we still see in theatre sitting as a design in a particular frame but here you can break that frame, you can go closer and he can focus your attention on just a little point here and a gesture here, and a gesture there and you know, on stage you will have to show with a torch yet it won’t be visible. Amol Palekar The point is …..Obviously two points come to my mind. First and foremost, suppose you are able to do it, and you are able to hold the audience then why not. The question is – yes, you do it for two hours, just keep one tableau and somebody the off sound is there. If that can hold then I think it will be a perfect valid theatre, why not? Bimal Lath Could it be that we can make 10 plays the same way? Amol Palekar Yes, why not? In fact I think on this issue I will say something which will immediately start a big fight so I will purposely started not for the sake of fight but because I believe in it also. -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

Oct-Dec-Vidura-12.Pdf

A JOURNAL OF THE PRESS INSTITUTE OF INDIA ISSN 0042-5303 October-DecemberJULY - SEPTEMBER 2012 2011 VOLUMEVolume 3 4 IssueISSUE 4 Rs 3 50 RS. 50 In a world buoyed by TRP ratings and trivia, QUALITY JOURNALISM IS THE CASUALT Y 'We don't need no thought control' n High time TAM/TRP era ended n The perils of nostalgia n You cannot shackle information now n Child rights/ child sexual abuse/ LGBT youth n Why I admire Justice Katju n In pursuance of a journalist protection law Responsible journalism in the age of the Internet UN Women: Promises to keep Your last line of defence n Alternative communication strategies help n The varied hues of community radio Indian TV news must develop a sense of The complex dynamics of rural Measuring n Golden Pen of Freedom awardee speaks n Soumitra Chatterjee’s oeuvre/ Marathi films scepticism communication readability n Many dimensions to health, nutrition n Tributes to B.K. Karanjia, G. Kasturi, Mrinal Gore Assam: Where justice has eluded journalists Bringing humour to features Book reviews October-December 2012 VIDURA 1 FROM THE EDITOR Be open, be truthful: that’s the resounding echo witch off the TV. Enough of it.” Haven’t we heard that line echo in almost every Indian home that owns a television set and has school-going children? “SIt’s usually the mother or father disciplining a child. But today, it’s a different story. I often hear children tell their parents to stop watching the news channels (we are not talking about the BBC and CNN here). -

Girish Karnad 1 Girish Karnad

Girish Karnad 1 Girish Karnad Girish Karnad Born Girish Raghunath Karnad 19 May 1938 Matheran, British India (present-day Maharashtra, India) Occupation Playwright, film director, film actor, poet Nationality Indian Alma mater University of Oxford Genres Fiction Literary movement Navya Notable work(s) Tughalak 1964 Taledanda Girish Raghunath Karnad (born 19 May 1938) is a contemporary writer, playwright, screenwriter, actor and movie director in Kannada language. His rise as a playwright in 1960s, marked the coming of age of Modern Indian playwriting in Kannada, just as Badal Sarkar did in Bengali, Vijay Tendulkar in Marathi, and Mohan Rakesh in Hindi.[1] He is a recipient[2] of the 1998 Jnanpith Award, the highest literary honour conferred in India. For four decades Karnad has been composing plays, often using history and mythology to tackle contemporary issues. He has translated his plays into English and has received acclaim.[3] His plays have been translated into some Indian languages and directed by directors like Ebrahim Alkazi, B. V. Karanth, Alyque Padamsee, Prasanna, Arvind Gaur, Satyadev Dubey, Vijaya Mehta, Shyamanand Jalan and Amal Allana.[3] He is active in the world of Indian cinema working as an actor, director, and screenwriter, in Hindi and Kannada flicks, earning awards along the way. He was conferred Padma Shri and Padma Bhushan by the Government of India and won four Filmfare Awards where three are Filmfare Award for Best Director - Kannada and one Filmfare Best Screenplay Award. Early life and education Girish Karnad was born in Matheran, Maharashtra. His initial schooling was in Marathi. In Sirsi, Karnataka, he was exposed to travelling theatre groups, Natak Mandalis as his parents were deeply interested in their plays.[4] As a youngster, Karnad was an ardent admirer of Yakshagana and the theater in his village.[] He earned his Bachelors of Arts degree in Mathematics and Statistics, from Karnatak Arts College, Dharwad (Karnataka University), in 1958. -

HAYAVADANA-Kumud Mehta.Pdf

HAYAVADANA Kumud Mehta Hayavadana had its premiere on May 20, 1983 at the Tata Theatre. Shri Vasantrao Patil, Chief Minister of Maharashtra, was the Chief Guest. Sponsored by the National Centre for the Performing Arts and the Goa Hindu Association, the first five shows scheduled at the Tata Theatre received an enthusiastic response from theatre-lovers and connoisseurs. Hayavadana was written by Girish Karnad during his tenure as a Homi Bhabha Fellow, and designed by the same creative team (Vijaya Mehta and Bhaskar Chandavarkar) which had successfully produced Shakuntala during the inaugural week of the Tata Theatre. Why did Vijaya Mehta and Bhaskar Chandavarkar, who had just recently concentrated their energies on a burning contemporary theme, the psyche of the dalit (Vijaya Mehta while directing Purusha and Bhaskar Chandavarkar in his film Atyachara) turn now to this play based on the Vetalapanchavimshati, the cycle of twenty-five tales related by a demon, · from one of the oldest collection of stories in Sanskrit literature? It is not difficult to surmise the reasons for the choice. For Hayavadana, as conceived by Girish Karnad, focusses on a crucial aspect of any kind of modern self-enquiry. Wherein lies an individual's identity? In mental equipment, knowledge as embodied in Devadatta's personality? Or, in the sheer evidence of the world known to Kapil through the sensat1ons of his body? Or, perhaps, in Padmini's subconscious yearning for a perfect partner embracing both these attributes? Besides, even as a modern seeks to understand the meaning of ·selfhood, does he not, with equal anguish, long to be unfragmented, integrated, whole? It is this philosophical undercurrent that runs through The Transposed Heads, Thomas Mann's renowned version of this story. -

Takes Pleasure in Inviting You To

Nalanda Celebrates 50th Golden Jubilee Year 2015 takes pleasure in inviting you to NALANDA - BHARATA MUNI SAMMAN - 2014 SAMAROHA and Premier of Latest Dance Production PRITHIVEE AANANDINEE at: Ravindra Natya Mandir, Prabhadevi, Mumbai on: Sunday, the 18th January, 2015 at: 6.30 p.m. NALANDA'S BHARATA MUNI SAMMAN Dedicated to the preservation and propagation of Indian dance in particular and Indian culture in general from its founding in 1966 Nalanda Dance Research Centre has unswervingly trodden on its chosen path with single minded determination. Nalanda has always upheld the pricelessness of all that is India and her great ancient culture which consists of the various performing arts, visual arts, the mother of all languages Sanskrit and Sanskritic studies , the religio- philosophical thought and other co-related facets. Being a highly recognized research centre, Nalanda recognizes and appreciates all those endeavours that probe deep into the all encompassing cultural phenomena of this great country. Very naturally these endeavours come from most dedicated individuals who not only delve into this vast ocean that is Indian culture but also have the intellectual calibre to unravel, re-interpret and re-invent this knowledge and wisdom to conform with their own times. From 2011 Nalanda has initiated a process of honouring such individuals who have acquired iconic status. By honouring them Nalanda is honouring India on behalf of all Indians. Hence the annual NALANDA - BHARATA MUNI SAMMAN Recipients for 2014 in alphabetical order Sangeet Martand Pandit Jasraj's (Music) Shri. Mahesh Elkuchwar (Theatre) Rajkumar Singhajit Singh (Dance) Sangeet Martand Pandit Jasraj San g eet M ar t an d Pan d it Jas raj 's achievements are beyond compare more so because vocal music is the most intimate and direct medium according to India's musical treatise and tradition. -

Social Science TABLE of CONTENTS

2015 Social Science TABLE OF CONTENTS Academic Tools 79 Labour Economics 71 Agrarian Studies & Agriculture 60 Law & Justice 53 Communication & Media Studies 74-78 Literature 13-14 Counselling & Psychotherapy 84 7LHJL *VUÅPJ[:[\KPLZ 44-48 Criminology 49 Philosophy 24 Cultural Studies 9-13 Policy Studies 43 Dalit Sociology 8 Politics & International Relations 31-42 Development Communication 78 Psychology 80-84 Development Studies 69-70 Research Methods 94-95 Economic & Development Studies 61-69 SAGE Classics 22-23 Education 89-92 SAGE Impact 72-74 Environment Studies 58-59 SAGE Law 51-53 Family Studies 88 SAGE Studies in India’s North East 54-55 Film & Theatre Studies 15-18 Social Work 92-93 Gender Studies 19-21 Sociology & Social Theory 1-7 Governance 50 Special Education 88 Health & Nursing 85-87 Sport Studies 71 History 25-30 Urban Studies 56-57 Information Security Management 71 Water Management 59 Journalism 79 Index 96-100 SOCIOLOGY & SOCIAL THEORY HINDUISM IN INDIA A MOVING FAITH Modern and Contemporary Movements Mega Churches Go South Edited by Will Sweetman and Aditya Malik Edited by Jonathan D James Edith Cowan University, Perth Hinduism in India is a major contribution towards ongoing debates on the nature and history of the religion In A Moving Faith by Dr Jonathan James, we see for in India. Taking into account the global impact and the first time in a single coherent volume, not only that influence of Hindu movements, gathering momentum global Christianity in the mega church is on the rise, even outside of India, the emphasis is on Hinduism but in a concrete way, we are able to observe in detail as it arose and developed in sub-continent itself – an what this looks like across a wide variety of locations, approach which facilitates greater attention to detail cultures, and habitus. -

2012 Cannes Film Festival Witnessed Massive Protest by the Attendants Especially the Feminists As They Found in Their Dismay

Article Rita Dutta Female Gaze: A Paradigm Shift Parched 2012 Cannes film festival witnessed massive protest by the attendants especially the feminists as they found in their dismay that there are no films from women directors. So, there is an absolute question of sexism in the selection process. The website change.org came up with the headline ‘Where are the Female Directors’ created quite a stir among the festival goers. Cannes is a ‘popular’ festival besides being overtly artistic. Its popularity is often intertwined by the ‘red carpet’ agenda. Women are all over but in a lesser & frivolous way. There is 1 mostly no ‘brains’ involved. The problem does not only lie in the conspicuous absence of films by the women film makers in the official competition of Cannes but also the severe dearth of women film makers in the whole world. This does raise an eye brow? It is kind of difficult to believe that no films from female directors was worthy of inclusion. May be the festival does not want to see a feminist point of view. Is not it sheer sexism that the festival shuts aside the perspective of half of the world? [Melissa Silverstein]. British director Andrea Arnold pointed out ‘It’s true the world over that there are just not many women directors. Cannes is small pocket that represents how it is there in the world.’ As the festival opened the news paper ‘Le Monde’ carried a protest letter from the feminist collective ‘La Barbe’, which was signed by notable French female film makers, including Virginie Despentes, Coline Serrau and Franny Cotlencon. -

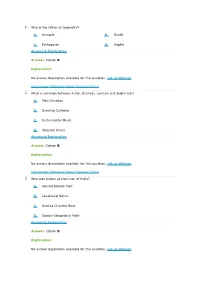

A. Aristotle B. Euclid C. Pythagoras D. Kepler Answer: Option B Explanation

1. Who is the father of Geometry? A. Aristotle B. Euclid C. Pythagoras D. Kepler Answer & Explanation Answer: Option B Explanation: No answer description available for this question. Let us discuss. View Answer Workspace Report Discuss in Forum 2. What is common between Kutty, Shankar, Laxman and Sudhir Dar? A. Film Direction B. Drawing Cartoons C. Instrumental Music D. Classical Dance Answer & Explanation Answer: Option B Explanation: No answer description available for this question. Let us discuss. View Answer Workspace Report Discuss in Forum 3. Who was known as Iron man of India? A. Govind Ballabh Pant B. Jawaharlal Nehru C. Subhas Chandra Bose D. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Answer & Explanation Answer: Option D Explanation: No answer description available for this question. Let us discuss. View Answer Workspace Report Discuss in Forum 4. The Indian to beat the computers in mathematical wizardry is A. Ramanujam B. Rina Panigrahi C. Raja Ramanna D. Shakunthala Devi Answer & Explanation Answer: Option D Explanation: No answer description available for this question. Let us discuss. View Answer Workspace Report Discuss in Forum 5. Jude Felix is a famous Indian player in which of the fields? A. Volleyball B. Tennis C. Football D. Hockey Answer & Explanation Answer: Option D 6. Who among the following was an eminent painter? A. Sarada Ukil B. Uday Shanker C. V. Shantaram D. Meherally Answer & Explanation Answer: Option A Explanation: No answer description available for this question. Let us discuss. View Answer Workspace Report Discuss in Forum 7. Professor Amartya Sen is famous in which of the fields? A. Biochemistry B. Electronics C. -

Girish Karnad: a Multifaceted Personality

Vol 6 Issue 7 April 2017 ISSN No : 2249-894X ORIGINAL ARTICLE Monthly Multidisciplinary Research Journal Review Of Research Journal Chief Editors Ashok Yakkaldevi Ecaterina Patrascu A R Burla College, India Spiru Haret University, Bucharest Kamani Perera Regional Centre For Strategic Studies, Sri Lanka Welcome to Review Of Research RNI MAHMUL/2011/38595 ISSN No.2249-894X Review Of Research Journal is a multidisciplinary research journal, published monthly in English, Hindi & Marathi Language. All research papers submitted to the journal will be double - blind peer reviewed referred by members of the editorial Board readers will include investigator in universities, research institutes government and industry with research interest in the general subjects. Regional Editor Dr. T. Manichander Advisory Board Kamani Perera Delia Serbescu Mabel Miao Regional Centre For Strategic Studies, Sri Spiru Haret University, Bucharest, Romania Center for China and Globalization, China Lanka Xiaohua Yang Ruth Wolf Ecaterina Patrascu University of San Francisco, San Francisco University Walla, Israel Spiru Haret University, Bucharest Karina Xavier Jie Hao Fabricio Moraes de AlmeidaFederal Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), University of Sydney, Australia University of Rondonia, Brazil USA Pei-Shan Kao Andrea Anna Maria Constantinovici May Hongmei Gao University of Essex, United Kingdom AL. I. Cuza University, Romania Kennesaw State University, USA Romona Mihaila Marc Fetscherin Loredana Bosca Spiru Haret University, Romania Rollins College, USA Spiru Haret University, Romania Liu Chen Beijing Foreign Studies University, China Ilie Pintea Spiru Haret University, Romania Mahdi Moharrampour Nimita Khanna Govind P. Shinde Islamic Azad University buinzahra Director, Isara Institute of Management, New Bharati Vidyapeeth School of Distance Branch, Qazvin, Iran Delhi Education Center, Navi Mumbai Titus Pop Salve R. -

The Master Playwrights and Directors

THE MASTER PLAYWRIGHTS AND DIRECTORS BIJAN BHATTACHARYA (1915–77), playwright, actor, director; whole-time member, Communist Party, actively associated with Progressive Writers and Artists Association and the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA); wrote and co-directed Nabanna (1944) for IPTA, starting off the new theatre movement in Bengal and continued to lead groups like Calcutta Theatre and Kabachkundal, with plays like Mora Chand (1961), Debigarjan [for the historic National Integration and Peace Conference on 21 February 1966 in Wellington Square, Calcutta], and Garbhabati Janani (1969), all of which he wrote and directed; acted in films directed by Ritwik Ghatak [Meghey Dhaka Tara (1960), Komal Gandhar (1961), Subarnarekha (1962), Jukti, Takko aar Gappo (1974)] and Mrinal Sen [Padatik (1973)]. Recipient of state and national awards, including the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for Playwriting in 1975. SOMBHU MITRA (1915–97), actor-director, playwright; led the theatre group Bohurupee till the early 1970s, which brought together some of the finest literary and cultural minds of the times, initiating a culture of ideation and producing good plays; best known for his productions of Dashachakra (1952), Raktakarabi (1954), Putulkhela (1958), Raja Oidipous (1964), Raja (1964), Pagla Ghoda (1971). Recipient of Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for Direction (1959), Fellow of the Sangeet Natak Akademi (1966), Padmabhushan (1970), Magsaysay Award (1976), Kalidas Samman (1983). HABIB TANVIR (1923–2009) joined the Indian People’s Theatre Association in the late forties, directing and acting in street plays for industrial workers in Mumbai; before moving to Delhi in 1954, when he produced the first version of Agra Bazar; followed by a training at the RADA, a course that left him dissatisfied, and he left incomplete. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. The Aesthetics of Emotional Acting: An Argument for a Rasa-based Criticism of Indian Cinema and Television PIYUSH ROY PhD South Asian Studies The University of Edinburgh 2016 1 DECLARATION This thesis has been composed by me and is my own work. It has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Piyush Roy 25 February 2017 2 For Thakuba (Aditya Prasanna Madhual), Aai (Malatilata Rout), Julki apa and Pramila Panda aunty II संप्रेषण का कोई भी माध्यम कला है और संप्रेषण का संदेश ज्ञान है. जब संदेश का उद्येश्य उत्तेजना उत्पन करता हो तब कला के उस 셂प को हीन कहते हℂ. जब संदेश ननश्वार्थ प्रेम, सत्य और महान चररत्र की रचना करता हो, तब वह कला पनवत्र मानी जाती है II ननदेशक चंद्रप्रकाश निवेदी, उपननषद् गंगा, एप.