Confidential – for Internal Use Only – Confidential Republican Hearing Guidance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The GIF That Keeps on Giving: Assignment Design with Looped Animations

The GIF that Keeps on Giving: Assignment Design with Looped Animations http://bit.ly/gifgive While an older format (created in 1987), GIFs (Graphics Interchange Format) have experienced a resurgence in popularity and use in the past decade. Due to the recent proliferation of digital platforms that host GIFs, the format as a means of communication and as an act of composition has become naturalized and therefore invisible. The rise in their popularity makes GIFs important for scholars of digital literacy and composition to understand and utilize in their teaching and research. We argue that their playful nature, ease of use, and delivery opens GIFs up for new avenues of research, inquiry, and analysis. As such, GIFs can be meaningfully incorporated into the composition classroom as critical components of assignment design and the feedback process. In this mini-workshop, we will introduce participants to pre-existing examples of GIF assignments we have used in courses, discuss avenues for pedagogical research, guide participants in the creation of new GIFs, and facilitate participants’ efforts to design assignments that use GIFs. Workshop Agenda http://bit.ly/gifgive Introduction ● Facilitators Icebreaker (5-10): Getting to Know You ● Participants Overview (10): The GIF That Keeps on Giving (http://bit.ly/gifgivepres) ● History (Matt) ● Integration into Current Communication (Jamie) ● Affective Nature of GIFs (Megan) ● Avenues of Inquiry ● As Digital Composition (Matt) ● Issues of Identity (Matt) ● Hierarchy/ Canon: r/highqualitygifs -

Syllabus 2021

History 201: The History of Now Professor Patrick Iber Spring 2021 / TuTh 9:30-10:45AM / online Office Hours: Wednesday 11am-1pm, online [email protected] (608) 298-8758 TA: Meghan O’Donnell, [email protected] Sections: W 2:25-3:15; W 3:30-4:20; W 4:35-5:25 This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA History is the study of change over time, and requires hindsight to generate insight. Most history courses stop short of the present, and historians are frequently wary of applying historical analysis to our own times, before we have access to private sources and before we have the critical distance that helps us see what matters and what is ephemeral. But recent years have given many people the sense of living through historic times, and clamoring for historical context that will help them to understand the momentous changes in politics, society and culture that they observe around them. This experimental course seeks to explore the last twenty years or so from a historical point of view, using the historian’s craft to gain perspective on the present. The course will consider major developments—primarily but not exclusively in U.S. history—of the last twenty years, including 9/11 and the War on Terror, the financial crisis of 2008 and its aftermath, social movements from the Tea Party to the Movement for Black Lives, and political, cultural, and the technological changes that have been created by and shaped by these events. This course is designed to be an introduction to historical reasoning, analysis, writing, and research. -

Onavo Protect for Mac

Onavo Protect For Mac 1 / 5 Onavo Protect For Mac 2 / 5 3 / 5 As part of this procedure, Onavo gets and analyzes facts about your cellular knowledge and application use. 1. onavo protect 2. onavo protect for pc 3. onavo protect vpn for iphone It is the Facebook owned Onavo Protect iOS app that is linked to in the Facebook iOS app settings under the “Protect” label.. After a paragraph about the protection that Onavo provides and some bullet points on how the service works, the company states that it is essentially spyware, which is on both the iOS App Store and the web.. Pinnacle stellt video capture for mac Free pinnacle video capture for mac free download - Adobe Presenter Video Express, Pinnacle Video Spin, 4Media Video Frame Capture for Mac, and many more programs. onavo protect onavo protect, onavo protect vpn for iphone, onavo protect ios, onavo protect vpn security, onavo protect for pc, onavo protect vpn download, onavo protect android, onavo protect for iphone, onavo protect apk for iphone, onavo protect uptodown Gratis Notifikasi Tidak Muncul Di Android “> Onavo Protect – VPN Security aplication For PC Windows 10/8/7/Xp/Vista & MAC To be capable to check out Onavo Shield – VPN Security aplication on your hard push or netbook machine owning windows seven eight ten and Macbook system you ought to start working with things like the actual lesson How to download Onavo Protect – VPN Security for pc windows 10 7 8 Mac on blustack? • 1st point you should have bluestack on your laptop.. Alternatives to Onavo Protect for Windows, Mac, Linux, Android, iPhone and more. -

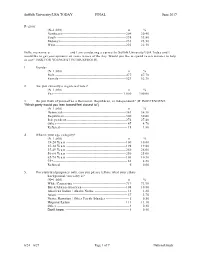

Final February Mass. Gop Likely Voters

SUPRC Likely Republican Voters FINAL FEBRUARY MASS. GOP LIKELY VOTERS GeoCode (N=500) n % Worcester / West ------------------------------------------------ 105 21.00 Northeastern ----------------------------------------------------- 192 38.40 Suffolk --------------------------------------------------------------- 25 5.00 Se Mass / Cape ------------------------------------------------- 178 35.60 *********************************************************************************************************** *Hello, my name is __________ and I am conducting a survey for Suffolk University and I would like to get your opinions on some issues of the day in Massachusetts. Would you be willing to spend less than five minutes answering some questions so that we can include your opinions? {IF YES PROCEED; IF NO, UNDECIDED, GO TO CLOSE} 1. Gender {BY OBSERVATION} (N=500) n % Male ---------------------------------------------------------------- 246 49.20 Female ------------------------------------------------------------ 254 50.80 2. What is your age category? (N=500) n % 18-35 Yrs. --------------------------------------------------------- 102 20.40 36-45 Yrs. ----------------------------------------------------------- 96 19.20 46-55 Yrs. --------------------------------------------------------- 101 20.20 56-65 Yrs. ----------------------------------------------------------- 92 18.40 66-75 Yrs. ----------------------------------------------------------- 51 10.20 Over 75 Yrs. -------------------------------------------------------- 44 8.80 Refused ------------------------------------------------------------- -

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: a Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov a Thesis

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: A Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov A thesis submitted to the Department of Political Science for honors Duke University Durham, North Carolina 2019 1 Note name change from National Front to National Rally in June 2018 1 Acknowledgements I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to a number of people who were integral to my research and thesis-writing journey. I thank my advisor, Dr. Michael Munger, for his expertise and guidance. I am also very grateful to my two independent study advisors, Dr. Beth Holmgren from the Slavic and Eurasian Studies department and Dr. Michèle Longino from the Romance Studies department, for their continued support and guidance, especially in the first steps of my thesis-writing. In addition, I am grateful to Dr. Heidi Madden for helping me navigate the research process and for spending a great deal of time talking through my thesis with me every step of the way, and to Dr. Richard Salsman, Dr. Genevieve Rousseliere, Dr. Anne Garréta, and Kristen Renberg for all of their advice and suggestions. None of the above, however, are responsible for the interpretations offered here, or any errors that remain. Thank you to the entire Duke Political Science department, including Suzanne Pierce and Liam Hysjulien, as well as the Duke Roman Studies department, including Kim Travlos, for their support and for providing me this opportunity in the first place. Finally, I am especially grateful to my Mom and Dad for inspiring me. Table of Contents 2 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………………4 Part 1 …………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………..5 Purpose ………………………………………………………………………………..13 Methodology and Terms ……………………………………………………………..16 Part 2 …………………………………………………………………………………………..18 The National Rally and Women ……………………………………………………..18 Marine Le Pen ………………………………………………………………………...26 Background ……………………………………………………………………26 Rise to Power and Takeover of National Rally ………………………….. -

The Tea Party Movement As a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 The Tea Party Movement as a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014 Albert Choi Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/343 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Tea Party Movement as a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014 by Albert Choi A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2014 i Copyright © 2014 by Albert Choi All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. THE City University of New York iii Abstract The Tea Party Movement as a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014 by Albert Choi Advisor: Professor Frances Piven The Tea Party movement has been a keyword in American politics since its inception in 2009. -

Clinton Lead Now 6% in Michigan (Clinton 48% - Trump 42% - Johnson 4.5% - Stein 2%)

P R E S S R E L E A S E FOR RELEASE: October 26, 2016 Contact: Steve Mitchell 248-891-2414 Clinton Lead Now 6% in Michigan (Clinton 48% - Trump 42% - Johnson 4.5% - Stein 2%) EAST LANSING, Michigan --- With thirteen days remaining before the election, the latest Fox 2 Detroit/Mitchell Poll of Michigan shows the race tightening further with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton leading businessman Donald Trump by a 6 percent margin in a in a four-way race that includes Libertarian Party candidate former New Mexico Gov. Gary Johnson and Green Party candidate Dr. Jill Stein. In the four-way race it is Clinton 48% - Trump 42% - Johnson 4.5% - Stein 1%, and 5% undecided. In a two-way race it is Clinton 50% - Trump 44% with 6% undecided. In the last FOX 2 Detroit/Mitchell Poll conducted Sunday night, Clinton’s lead was 8% and she led by 13% on October 18th, the night before the last debate. The IVR (automated) poll of 1,030 likely voters in the November 2016 General Election was conducted by Mitchell Research & Communications on October 25, 2016 and has a Margin of Error of + or – 2.78% at the 95% level of confidence. “The race inched closer last night with Clinton losing a point and Trump gaining a point. Gary Johnson and Jill Stein are doing a little bit better than they were doing on Sunday. However, Clinton still has a strong lead with absentee voters who have already cast a ballot. Clinton is still in a strong position, but her support has eroded in the past week,” Steve Mitchell, CEO of Mitchell Research & Communications said. -

A Critical Discourse Analysis

How Facebook Comments Reflect Certain Characteristics Of Islamophobia: A Critical Discourse Analysis By Annabell Curci-Wallis UPPSALA UNIVERSITY Department of Theology Master Programme in Religion in Peace and Conflict Master thesis 30 credits Spring 2019 Supervisor: Mia Lövheim Facebook Comments and the Reflection of Characteristics of Islamophobia 2 Thank you: I am extremely grateful to my supervisor, Mia Lövheim, who was patient with me, advised me, and send insightful comments and suggestions even when she had the flu, so I could finish on time. I could not have done it without you. Thank you. I also like to say thank you to my husband, and my sweet daughter, who both supported me by giving me enough time and space, to finish my work. Abstract: This study is a contribution to the limited knowledge of how different types of media content (about Muslims and extremism) posted and shared on Facebook might influence corresponding user comments. Through analyzing the discourse of user comments this study aims to identify how comments might reflect certain characteristics of Islamophobia, and to which themes in Facebook posts commentators relate to the most. The linguistic analysis is guided by the use of critical discourse analysis. For the purpose of this study, three different types of articles/video and the corresponding comments are analyzed. Two of the articles/video that I will analyze are from unreliable media sources, and one of the articles is from a credible media source. The linguistic analysis showed that the majority of commentators expressed that they believe the claims made in the articles/video about Muslims and extremism are true. -

How Apps on Android Share Data with Facebook (Even If You Don’T Have a Facebook Account)

How Apps on Android Share Data with Facebook (even if you don’t have a Facebook account) December 2018 How Apps on Android Share Data with Facebook Privacy International is a UK-registered charity (1147471) that promotes the right to privacy at an international level. It is solely responsible for the research and investigation underpinning its reports. 2 How Apps on Android Share Data with Facebook Executive Summary Previous research has shown how 42.55 percent of free apps on the Google Play store could share data with Facebook, making Facebook the second most prevalent third-party tracker after Google’s parent company Alphabet.1 In this report, Privacy International illustrates what this data sharing looks like in practice, particularly for people who do not have a Facebook account. This question of whether Facebook gathers information about users who are not signed in or do not have an account was raised in the aftermath of the Cambridge Analytica scandal by lawmakers in hearings in the United States and in Europe.2 Discussions, as well as previous fines by Data Protection Authorities about the tracking of non-users, however, often focus on the tracking that happens on websites.3 Much less is known about the data that the company receives from apps. For these reasons, in this report we raise questions about transparency and use of app data that we consider timely and important. Facebook routinely tracks users, non-users and logged-out users outside its platform through Facebook Business Tools. App developers share data with Facebook through the Facebook Software Development Kit (SDK), a set of software development tools that help developers build apps for a specific operating system. -

Suffolk University/USA TODAY FINAL June 2017

Suffolk University/USA TODAY FINAL June 2017 Region: (N=1,000) n % Northeast ---------------------------------------------------------- 204 20.40 South --------------------------------------------------------------- 338 33.80 Midwest ------------------------------------------------------------ 235 23.50 West ---------------------------------------------------------------- 223 22.30 Hello, my name is __________ and I am conducting a survey for Suffolk University/USA Today and I would like to get your opinions on some issues of the day. Would you like to spend seven minutes to help us out? {ASK FOR YOUNGEST IN HOUSEHOLD} 1 Gender (N=1,000) n % Male ---------------------------------------------------------------- 477 47.70 Female ------------------------------------------------------------- 523 52.30 2. Are you currently a registered voter? (N=1,000) n % Yes--------------------------------------------------------------- 1,000 100.00 3. Do you think of yourself as a Democrat, Republican, or Independent? {IF INDEPENDENT, “Which party would you lean toward/feel closest to”} (N=1,000) n % Democrat ---------------------------------------------------------- 361 36.10 Republican -------------------------------------------------------- 300 30.00 Independent ------------------------------------------------------ 274 27.40 Other ---------------------------------------------------------------- 47 4.70 Refused ------------------------------------------------------------- 18 1.80 4. What is your age category? (N=1,000) n % 18-24 Years ------------------------------------------------------ -

“How to Make a GIF” Guideline

1 Sigrid Nagele Otelo eGen, Linz Austria HOW TO MAKE GIFs Creating dynamic pictures for the web, social media and presentations 2 What is a GIF? • „Graphics Interchange Format“ • chains together multiple pictures into a single animated image • GIFs have exploded in popularity in recent years, so they are very useful to reach a lot of people, especially on social media 3 How to make a GIF… …using the platform GIPHY: Giphy is super quick and easy to use. It will take you less than 5 minutes to create a GIF, it offers different ways to do it and you don‘t have to register. • Go to: www.giphy.com • Click „create“ 4 How to make a GIF… • Choose the material you want to make a GIF from • 3 Options: 5 How to make a GIF… • ...from pictures/photos on my computer: • Select the pics you want to have in the GIF loop from your files: 6 How to make a GIF… • Adjust the speed: • Options for text: 7 How to make a GIF… • Add tags to your GIF!!! like „bioeconomy“, „innovation“, „bloom“, „recycling“ • Upload! 8 How to make a GIF… • Now your GIF is ready to be shared or to download Here you find the link to the GIF itself • download the GIF: Different format versions of right-click on the image > save image as… the GIF are available. 9 How to make a GIF… • Make a GIF from online images/videos: (make sure you do not infringe a copyright!!!) • Add more images for a dynamic GIF or add a text animation Upload! Add more images 10 How to make a GIF… GIFs are nice to be shared on social media channels as Facebook, Twitter or Instagram and to be used in presentations. -

Defending the Indispensable: Allegations of Anti- Conservative Bias, Deep Fakes, and Extremist Content Don’T Justify Section 230 Reform

Defending the Indispensable: Allegations of Anti- Conservative Bias, Deep Fakes, and Extremist Content Don’t Justify Section 230 Reform Matthew Feeney CSAS Working Paper 20-11 Should Internet Platform Companies Be Regulated – And If So, How? Defending the Indispensable: Allegations of Anti-Conservative Bias, Deep Fakes, and Extremist Content Don't Justify Section 230 Reform Matthew Feeney Director of the Cato Institute’s Project on Emerging Technologies Introduction When President Clinton signed the Telecommunications Act of 1996 it’s unlikely he knew that he was signing a bill that included what has come to be called the “Magna Carta of the Internet.”1 After all, the law was hundreds of pages long, including seven titles dealing with broadcast services, local exchange carriers, and cable. The Internet as we know it didn’t exist in 1996. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg was 11 years old, and two Stanford University PhD students, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, had only just begun a project that would come to be known at Google. Some didn’t even think that the Internet would last, with Ethernet co-inventor Robert Metcalfe predicting in 1995 that “the internet will soon go supernova and in 1996 will catastrophically collapse.”2 The U.S. Supreme Court would rule much of Title V of the law, otherwise known as the Communications Decency Act, to be unconstitutional in 1997.3 However, a small provision of the law – Section 230 – survived. This piece of legislation” stated that interactive computer services could not be considered publishers of most third-party content or be held liable for moderating content.