Weeping in Sharps and Flats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diamm Facsimiles 6

DIAMM FACSIMILES 6 DI MM DIGITAL IMAGE ACHIVE OF MEDIEVAL MUSIC DIAMM COMMITTEE MICHAEL BUDEN (Faculty Board Chair) JULIA CAIG-McFEELY (Diamm Administrator) MATIN HOLMES (Alfred Brendel Music Librarian, Bodleian Library) EMMA JONES (Finance Director) NICOLAS BELL HELEN DEEMING CHISTIAN LEITMEIR OWEN EES THOMAS SCHMIDT diamm facsimile series general editor JULIA CAIG-McFEELY volume editors ICHAD WISTEICH JOSHUA IFKIN The ANNE BOLEYN MUSIC BOOK (Royal College of Music MS 1070) Facsimile with introduction BY THOMAS SCHMIDT and DAVID SKINNER with KATJA AIAKSINEN-MONIER DI MM facsimiles © COPYIGHT 2017 UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD PUBLISHED BY DIAMM PUBLICATIONS FACULTY OF MUSIC, ST ALDATES, OXFORD OX1 1DB ISSN 2043-8273 ISBN 978-1-907647-06-2 SERIES ISBN 978-1-907647-01-7 All rights reserved. This work is fully protected by The UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. No part of the work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise without the prior permission of DIAMM Publications. Thomas Schmidt, David Skinner and Katja Airaksinen-Monier assert the right to be identified as the authors of the introductory text. Rights to all images are the property of the Royal College of Music, London. Images of MS 1070 are reproduced by kind permission of the Royal College of Music. Digital imaging by DIAMM, University of Oxford Image preparation, typesetting, image preparation and page make-up by Julia Craig-McFeely Typeset in Bembo Supported by The Cayzer Trust Company Limited The Hon. Mrs Gilmour Printed and bound in Great Britain by Short Run Press Exeter CONTENTS Preface ii INTODUCTION 1. -

Concerning the Ontological Status of the Notated Musical Work in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

Concerning the Ontological Status of the Notated Musical Work in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries Leeman L. Perkins In her detailed and imaginative study of the concept of the musical work, The Imag;inary Museum of Musical Works (1992), Lydia Goehr has made the claim that, prompted by "changes in aesthetic theory, society, and poli tics," eighteenth century musicians began "to think about music in new terms and to produce music in new ways," to conceive of their art, there fore, not just as music per se, but in terms of works. Although she allows that her view "might be judged controversial" (115), she asserts that only at the end of the 1700s did the concept of a work begin "to serve musical practice in its regulative capacity," and that musicians did "not think about music in terms of works" before 1800 (v). In making her argument, she pauses briefly to consider the Latin term for work, opus, as used by the theorist and pedagogue, Nicolaus Listenius, in his Musica of 1537. She acknowledges, in doing so, that scholars in the field of music-especially those working in the German tradition-have long regarded Listenius's opening chapter as an indication that, by the sixteenth century, musical compositions were regarded as works in much the same way as paintings, statuary, or literature. She cites, for example, the monographs devoted to the question of "musical works of art" by Walter Wiora (1983) and Wilhelm Seidel (1987). She concludes, however, that their arguments do not stand up to critical scrutiny. There can be little doubt, surely, that the work-concept was the focus of a good deal of philosophical dispute and aesthetic inquiry in the course of the nineteenth century. -

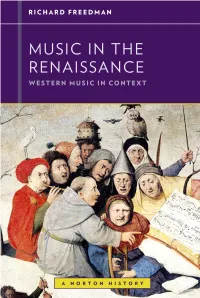

MUSIC in the RENAISSANCE Western Music in Context: a Norton History Walter Frisch Series Editor

MUSIC IN THE RENAISSANCE Western Music in Context: A Norton History Walter Frisch series editor Music in the Medieval West, by Margot Fassler Music in the Renaissance, by Richard Freedman Music in the Baroque, by Wendy Heller Music in the Eighteenth Century, by John Rice Music in the Nineteenth Century, by Walter Frisch Music in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries, by Joseph Auner MUSIC IN THE RENAISSANCE Richard Freedman Haverford College n W. W. NORTON AND COMPANY Ƌ ƋĐƋ W. W. Norton & Company has been independent since its founding in 1923, when William Warder Norton and Mary D. Herter Norton first published lectures delivered at the People’s Institute, the adult education division of New York City’s Cooper Union. The firm soon expanded its program beyond the Institute, publishing books by celebrated academics from America and abroad. By midcentury, the two major pillars of Norton’s publishing program—trade books and college texts— were firmly established. In the 1950s, the Norton family transferred control of the company to its employees, and today—with a staff of four hundred and a comparable number of trade, college, and professional titles published each year—W. W. Norton & Company stands as the largest and oldest publishing house owned wholly by its employees. Copyright © 2013 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Editor: Maribeth Payne Associate Editor: Justin Hoffman Assistant Editor: Ariella Foss Developmental Editor: Harry Haskell Manuscript Editor: Bonnie Blackburn Project Editor: Jack Borrebach Electronic Media Editor: Steve Hoge Marketing Manager, Music: Amy Parkin Production Manager: Ashley Horna Photo Editor: Stephanie Romeo Permissions Manager: Megan Jackson Text Design: Jillian Burr Composition: CM Preparé Manufacturing: Quad/Graphics-Fairfield, PA A catalogue record is available from the Library of Congress ISBN 978-0-393-92916-4 W. -

BYRD 1588 Psalmes, Sonets & Songs of Sadnes and Pietie

BYRD 1588 Psalmes, Sonets & songs of sadnes and pietie Grace Davidson SOPRANO Martha McLorinan MEZZO-SOPRANO Nicholas Todd TENOR ALAMIRE FRETWORK DAVID SKINNER BYRD 1588 Original order in 1588 publication DISC TWO Psalmes, Sonets & songs of sadnes and pietie noted in square brackets Psalms William Byrd (1543–1623) 1. Even from the depth [10] [1:48] Grace Davidson, soprano 2. Blessed is he that fears the Lord [8] [3:51] Martha McLorinan, mezzo-soprano DISC ONE 3. How shall a young man prone Nicholas Todd, tenor to ill [4] [2:24] Psalms 4. Help Lord for wasted are Fretwork 1. O God give ear [1] [3:50] those men [7] [4:56] Alamire, directed by David Skinner 2. Mine eyes with fervency of 5. Lord in thy wrath reprove me not [9] [4:04] sprite [2] [3:48] 3. My soul oppressed with care Sonnets and pastorals and grief [3] [2:22] 6. Though Amaryllis dance 4. O Lord how long wilt thou forget [5] [3:48] in green [12] [5:53] 5. O Lord who in thy sacred tent [6] [4:00] 7. Constant Penelope [23] [2:30] 8. I joy not in no earthly bliss [11] [3:40] Sonnets and pastorals 9. As I beheld I saw a 6. O you that hear this voice [16] [6:15] herdman wild [20] [4:59] 7. Ambitious love [18] [2:29] 10. Where fancy fond [15] [5:19] 8. Although the heathen poets [21] [1:10] 11. What pleasure have great 9. My mind to me a kingdom Is [14] [6:02] princes [19] [4:47] 10. -

Josquin Des Prez Discography

Josquin des Prez Discography Compiled by Jerome F. Weber This discography of Josquin des Prez (Josquin Lebloitte dit des Prez, formerly cited as Josquin Desprez or Josquin des Près and alphabetized under D, J or P), compiled by Jerome F. Weber, adopts the format of the Du Fay discography previously posted on this website. It may be noted that at least three book titles since 2000 have named him simply “Josquin,” bypassing the spelling problem. Acknowledgment is due to Pierre-F. Roberge and Todd McComb for an exhaustive list of records containing Josquin’s music in www.medieval.org/emfaq. It incorporates listings from the work of Sydney Robinson Charles in Josquin des Prez: A Guide to Research (Garland Composer Resource Manuals, 1983) and Peter Urquhart in The Josquin Companion (ed. Richard Sherr, Oxford, 2000), which continued where Charles left off. The last two lists each included a title index. This work has also used the following publications already incorporated in the three cited discographies. The 78rpm and early LP eras were covered in discographic format by The Gramophone Shop Encyclopedia of Recorded Music (three editions, 1936, 1942, 1948) and The World’s Encyclopaedia of Recorded Music (three volumes, 1952, 1953, 1957). James Coover and Richard Colvig compiled Medieval and Renaissance Music on Long-Playing Records in two volumes (1964 and 1973), and Trevor Croucher compiled Early Music Discography from Plainsong to the Sons of Bach (Oryx Press, 1981). The Index to Record Reviews compiled by Kurtz Myers (G. K. Hall, 1978) provided useful information. Michael Gray’s classical-discography.org has furnished many details. -

Allinson Early Music Performer Article 2017.Pdf

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Please cite this publication as follows: Allinson, D. (2017) Museum pieces? sixteenth-century sacred polyphony and the modern English tradition of A Cappella performance. Early Music Performer, 41. pp. 3-9. ISSN 1477-478X. Link to official URL (if available): http://www.earlymusic.info/Performer.php This version is made available in accordance with publishers’ policies. All material made available by CReaTE is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Contact: [email protected] Museum Pieces? Sixteenth-Century Sacred Polyphony and the Modern English Tradition of A Cappella Performance David Allinson The audience of several dozen, sitting in hard pews, breaks into applause as a crocodile of singers, clad in black cotton clothes and black shoes, files neatly onto the chancel steps. The conductor takes his place in front of the choir, the applause dies away and an intense, still silence frames the polyphonic mass and motets that reverberate amid stone arcades. After an hour or so the music dies away; the audience is roused from focused contemplation to appreciation; the performers acknowledge the applause and depart for the pub. This scenario will be familiar to any reader of the organisations in London, which exert a huge journal who has, like me, played the part of influence over amateur and professional singing listener, singer or conductor -

Peterhouse Partbooks

Music from the Peterhouse partbooks Tallis, Jones, Taverner & Aston Music from the Peterhouse partbooks Tallis,Friday, OctoberJones, 24, 2008, at 8 p.m.Taverner &Aston First Church in Cambridge, Congregational Program Thomas Tallis (c. 1505–1585) Ave rosa sine1 spinis Robert Fayrfax (1464–1521) That was my woo / PD AS Edmund Turges2 (b. c. 1450) Alas it is I / MN MS PG Three rounds William Daggere (?) Downbery down / JM MS AS Doctor Cooper (?) Alone I leffe alone / AC MS JM Kempe (?) Hey now now / AS JM MS William Cornysh (d. 1523) Adew mes amours et mon desyre / LB PD AS AC Robert Jones (fl. c. 1520–35) Magnificat3 intermission John Taverner (c. 1490–1545) Mater Christi4 sanctissima Fayrfax Most clere of colour / MN JM AC Cornysh5 A the syghes / NB PD MS anonymous I am a joly foster / JM AC CB anonymous Madame d’amours / BW MN AS GB Hugh Aston (c. 1485–1558) Ave Maria ancilla6 trinitatis Noël Bisson Pamela Dellal Allen Combs Cameron Beauchamp Lydia Brotherton MartinBlue Near HeronJason McStoots Glenn Billingsley Brenna Wells Aaron Sheehan Paul Guttry Mark Sprinkle Scott Metcalfe, director Pre-concert talk by Christopher Martin, Boston University We dedicate this concert to the memory of Mimi Sprinkle, mother of Mark, and a great fan and supporter of Blue Heron. Blue Heron Renaissance Choir · 45 Ash Street · Auburndale, MA 02466 (617) 960-7956 · [email protected] · www.blueheronchoir.org This organization is funded in part by the Massachusetts Cultural Council, a state agency. The historicalSacred record permits& secularus to imagine songA greate nombre inof themEngland, whych purchased c. -

Katherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn, Jane Seymour, Anne of Cl

THE MUSICAL EDUCATION AND INVOLVEMENT OF THE SIX WIVES OF HENRY VIII: Katherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn, Jane Seymour, Anne of Cleves, Katherine Howard and Katherine Parre A THESIS IN MUSICOLOGY Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC by BROOKE CATHERINE LITTLE B.M. University of Missouri-Columbia 2005 M. M. Ed. University of Missouri- Columbia 2008 Kansas City, Missouri 2017 2017 Brooke Catherine Little All Rights Reserved THE MUSICAL EDUCATION AND INVOLVEMENT OF THE SIX WIVES OF HENRY VIII Brooke Catherine Little, candidate for the Master of Music Degree University of Missouri- Kansas City, 2017 ABSTRACT The first half of sixteenth-century England was a land permeated by religious upheaval and political instability. Despite being a land fraught with discord, it was a time of great advances in education, theology, and the musical arts. Henry VIII, king of England during this time, married six different women during his reign, which lasted from 1509 to 1547. Each queen experienced a different musical education, which resulted in musical involvement that reflected that queen’s own background and preferences. By and large, each of the reasons discussed in this thesis; religious, financial, social, sexual and even at times political, circle back to the idea of the manifestation and acquisition of power. Inadvertently, the more power the queen or queen in training gained as she climbed the social ladder, the better her chances of her survival were compared to her lower- class counterparts. Spanish born, Katherine of Aragon was raised at the court of Ferdinand and Isabella, where she was educated in both singing and instrumental performance, as well as dance. -

CHORAL MUSIC in the White House 8 2266

JJune/Julyune/July 22012012 CONTENTS VVol.ol. 5522 • nono 1111 A COPLAND PORTRAIT Choral Music MEMORIES OF A FRIENDSHIP, AND THOUGHTS ABOUT HIS INFLUENCE 00 ON AMERICAN CHORAL MUSIC in the White House 8 2266 TThehe AACDACDA NNationalational SSymposiumymposium onon AmericAmericaann CChoralhoral MMusicusic The Choral Arrangements TTHEHE of Alice Parker SSEARCHEARCH and Robert Shaw FFOROR AANN American Style 1188 3300 ARRTICLESTICLES INNSIDESIDE 8 CChoralhoral MMusicusic iinn tthehe WWhitehite HHouseouse 2 From the Executive Director 4 From the President bbyy DDonaldonald TTrottrott 6 From the Guest Editor 7 Letters to the Editor 1188 CChoralhoral MMusicusic iinn tthehe WWhitehite HHouse:ouse: AAnn AAfterwordfterword 52-55 Nat'l Honor Choir Info. bbyy DDonaldonald OOglesbyglesby 66-68 Nat'l Music in Worship Festival Choir Info. 88 Advertisers’ Index TThehe AACDACDA NNationalational SSymposiumymposium oonn AAmericanmerican CChoralhoral MMusic:usic: 2222 TThehe SSearchearch fforor anan AmericanAmerican SStyletyle The Choral Journal is the official publication of The American Choral Directors Association (ACDA). ACDA is bbyy JJohnohn SSilantienilantien a nonprofit professional organization of choral directors from schools, colleges, and universities; community, 2266 A CCoplandopland PPortrait:ortrait: MMemoriesemories ofof a FriendshipFriendship andand TThoughtshoughts church, and professional choral ensembles; and industry and institutional organizations. Choral Journal circula- aaboutbout HHisis IInfluencenfluence oonn AAmericanmerican CChoralhoral MMusicusic tion: 19,000. bbyy DDavidavid CConteonte Annual dues (includes subscription to the Choral Journal): 3300 TThehe CChoralhoral AArrangementsrrangements ooff AAlicelice PParkerarker aandnd RRobertobert ShawShaw Active $95, Industry $135, Institutional $110, Retired $45, and Student $35. One-year membership begins bbyy JJimim TTayloraylor on date of dues acceptance. Library annual subscription rates: U.S. $45; Canada $50; Foreign $85. -

Hieronymus Praetorius Alamire

H I E R O N Y M U S P R A E T O R I U S Motets in 8, 10, 12, 16 & 20 Parts A L A M I R E His Majestys Sagbutts & Cornetts Stephen Farr ORGAN DAVID SKINNER HIERONYMUS PRAETORIUS (1560–1629) DISC ONE DISC TWO Motets in 8, 10, 12, 16 & 20 Parts 1. Dixit Dominus a12 [5:49] 1. Laudate Dominum a8 [4:36] Alamire 2. Nunc dimittis a8 [7:34] 2. Sanctus summum [4:28] His Majestys Sagbutts & Cornetts Stephen Farr, organ 3. Sequentia: Grates nunc omnes [8:03] 3. Agnus Dei summum [5:34] David Skinner 4. Angelus ad pastores ait a12 [5:59] 4. Iubilate Deo a12 [4:59] 5. Ecce Dominus veniet a8 [4:52] 5. Ecce quam bonum a8 [4:06] 6. Decantabat populus a20 [5:44] 6. Levavi oculos meos a10 [5:28] 7. Kyrie summum [9:12] 7. Sequentia: Victimae paschali laudes [7:47] 8. Gloria summum [10:29] 8. Exultate iusti a16 [5:36] Total playing time [57:46] Total playing time [42:39] Hieronymus Praetorius in the Johanneum Latin school. After beginning organ instruction with his father, Jacob Praetorius I At the beginning of the seventeenth century, (c. 1540–1586), he studied with Hinrich thor Hieronymus Praetorius (1560–1629) of Molen, the Petrikirche organist and in 1574 Hamburg stood pre-eminent among musicians was sent by the elders of the Jacobikirche to in north Germany. He was the first significant Cologne for two years of further study with figure in the city’s early music history, followed Albin Walran. -

The Transmission and Reception of the Marian Antiphon in Early Modern Britain

The Transmission and Reception of the Marian Antiphon in Early Modern Britain Volume 1 of 2 Daisy M. Gibbs Submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Arts and Cultures, Newcastle University May 2018 Abstract A substantial proportion of extant pre-Reformation sacred music by English composers survives only in Elizabethan manuscript sources. The evident popularity of this music among copyists and amateurs after it became obsolete in public worship remains largely unexplained, however. Using the Marian votive antiphon as a case study, exemplified by the surviving settings of the popular antiphon text Ave Dei patris filia, this thesis comprises a reception history of pre-Reformation sacred music in post-Reformation England. It sheds light on the significance held by pre-Reformation music to Elizabethan copyists, particularly in relation to an emergent sense of British nationhood and the figure of the composer as a category of reception, in doing so problematising the long-standing association between the copying of pre-Reformation sacred music and recusant culture. It also uses techniques of textual filiation to trace patterns of musical transmission and source interrelationships, and thereby to gauge the extent of manuscript attrition during the sixteenth-century Reformations. Chapters 1 and 2 discuss the production of the Ave Dei patris antiphon corpus, particularly the ways in which its meanings were shaped by composers in the decades before the English Reformations. Chapter 3 concerns the transformations undergone by the Marian antiphon during the 1540s and 1550s and following the Elizabethan Settlement. The remaining chapters discuss the post-1559 afterlife of pre-Reformation polyphony. -

16Th Century EDITIONS

16th century can do here. Each two-page spread of about 20 x 29cm can also be easily scanned. Ten of the madrigals (I-VI, XII-XIII, and XV-XVI) EDITIONS are by Petrarch, the rest anonymous. The first six set the six stanzas of Petrarch’s 8th Sestina, Là ver’ l’aurora, che Giovanni de Macque: Il Primo Libro de sì dolce l’aura to music, as was also done (in part or in full) Madrigali a Quattro Voci by Palestrina, de Lasso, Pietro Vinci, Mateo Flecha el Edited by Giuseppina Lo Coco Joven, Striggio, and undoubtedly others before and after Biblioteca Musicale n. 32. (LIM, 2017) de Macque. Each stanza has six lines, without rhyme, x+143pp. €25 each ending with one of six words, according to an ever- ISBN 9788870969252 revolving order whereby abcdef changes to faebdc. These six madrigals are in F major, with numbers 2 and 5 ending iovanni (Jean) de Macque was born circa 1550 on the dominant. De Macque did not set Petrarch’s in Valenciennes, then part of the Spanish concluding tercet, in which the six words appear in the Netherlands, but he was active in Italy throughout middle and end of three lines – perhaps there not being G enough text for another madrigal. The tercet is more a his career, in Rome for a decade (from 1574?), during which time he published five books of madrigals (for A. Gardano, poetic feat than a climax: it sums up the unified theme Venice) and became the organist at San Luigi dei Francesi, of frustration with the impossibility of moving Laura’s and in Naples from 1585 until his death in 1614.